Abstract

This paper examines whether the stock price of the rating agency Moody’s reacts negatively to rating actions that could indicate low rating quality. The reaction to rating reversals, which Moody’s describes as particularly damaging to investors, is economically significant. It suggests that market discipline has the potential to influence agency behavior. On the other hand, defaults of highly rated issuers do not consistently impact Moody’s stock price. The focus on reversals and the neglect of default events are consistent with either collusion or with misconceptions of how rating quality should be evaluated. Both interpretations question whether market discipline can be sufficient to ensure a socially optimal rating policy within the current environment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

News release “Moody’s Confirms External Review of European CPDO Rating Process”, available on http://ir.moodys.com/RELEASEDETAIL.cfm?releaseid=311726

Moody’s and S&P have an estimated market share of 80% measured by revenue, cf. US Senate Report 109–326, 2006.

According to Moody’s, a rating is meant to provide “a signal that looks through cycles and immaterial events and focuses on long-term creditworthiness” (Mahoney 2002, p.3).

S&P, which itself pursues non-rating related activities, is part of McGraw-Hill; and Fitch is part of the France-based company Fimalac, which now focuses on risk management but was an industrial conglomerate before 2005. In 2004, halfway through the sample period, Fitch contributed 36% to Fimalacs’ revenue while the financial services segment, which comprises the S&P rating business, contributed 39% to McGraw-Hill’s revenue.

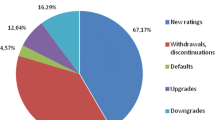

Source: Moody’s annual reports. Other business sectors are structured finance ratings, research, and Moody’s KMV. From 1998 to 2010, the average revenue share of structured finance was 32.2%. The structured finance share exceeded the traditional rating business in the years 2005 to 2007.

I am indebted to Ken French for making this data available on http://mba.tuck.dartmouth.edu/pages/faculty/ken.french/data_library.html.

I examine estimated senior ratings as described in Gupta and Parwani (2009). Some changes in issuer ratings are due to changes in the methodology used to derive issuer ratings from individual bond ratings. I use a flag contained in the database as well as the detailed rating information provided on www.moodys.com to identify actual rating actions as opposed to changes due to methodology, and use only actual rating actions in my analysis.

Cf. “Moody’s lowers bank ratings following refinement of methodology”, Global Credit Research, 4/10/2007. The 2006 change in methodology is described in “Moody’s publishes final Methodology and related research for Loss-Given-Default Assessments and Probability-Of-Default Ratings”, Global Credit Research, 8/23/2006. Both reports are available on www.moodys.com.

To further check robustness, partly motivated by the fact that reversal and default events appear to be clustered (cf. Fig. 1), I estimate standard errors with the Newey-West estimator and a lag length of 21 (= 1 month). Results do not change conspicuously. For example, the t-statistics of the reversal dummy change from −2.34 to −2.28 (no winsorization) and from −2.65 to −2.64 (winsorization).

Fortune 500 lists are available on http://money.cnn.com/magazines/fortune/fortune500_archive. One could also use the volume of outstanding bonds to classify issuers, but this information is not contained in the database available to me.

Defaults of subsidiaries are not taken into account when determining the number of defaults on a given day.

One could argue that one should ignore the estimated impact of non-eminent reversals because it is not statistically significant. Ignoring insignificant coefficients is ad hoc, though. On the other hand, it does not have a great effect. Ignoring the −0.00129 leads to a estimated cumulative loss of −25.2% (=(1−0.01110)26−1), which is still economically significant.

Classifications are available on www.moodys.com.

Within a multivariate regression, overlapping event windows also reduce the precision of the estimation. However, by construction, regression coefficients are estimates of partial effects, which means that they can easily be interpreted in a standard way.

Currently, there are ten agencies that enjoy the “Nationally Recognized Statistical Rating Organization” status awarded by the SEC (cf. http://www.sec.gov/answers/nrsro.htm)—an important prerequisite for widespread investor use of an agency’s ratings.

λ = 14,400 is a common choice for monthly data. Pedersen (2001) recommends λ > 100,000.

References

Allen AC, Dudney DM (2008) The impact of rating agency reputation on local government bond yields. J Financ Serv Res 33:57–76

Altman E, Rijken H (2006) A point-in-time perspective on through-the-cycle ratings. Financ Anal J 62:54–70

Becker B, Milbourn T (2011) How did increased competition affect credit ratings? J Financ Econ 101:2011–2012

Binder JJ (1985) On the use of the multivariate regression model in event studies. J Account Res 23:370–383

Bittlingmayer G, Hazlett TW (2000) DOS Kapital: has antitrust action against Microsoft created value in the computer industry. J Financ Econ 55:329–359

Blume ME, Kim F, MacKinlay CA (1998) The declining credit quality of US corporate debt: myth or reality? J Finance 53:1389–2013

Bolton P, Freixas X, Shapiro XJD (2012) The credit ratings game. J Finance, forthcoming

Brown SJ, Warner JB (1980) Measuring security price performance. J Financ Econ 8:205–258

Calomiris CW (2009) A recipe for ratings reform. Economist Voice 6:5

Campbell JY, Taksler GB (2003) Equity volatility and corporate bond yields. J Finance 58:2321–2349

Cantor R (2001) Moody’s investors service response to the consultative paper issued by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision and its implications for the rating agency industry. J Bank Finance 25:171–186

Cantor R, Mann C (2003) Measuring the performance of corporate bond ratings. Special comment, Moody’s Investors Service

Cantor R, Packer F (1997) Differences of opinion and selection bias in the credit rating industry. J Bank Finance 21:1395–1417

Cornett MM, Mehran H, Tehranian H (1998) The impact of risk-based premiums on FDIC-insured institutions. J Financ Serv Res 13:153–169

Coval J, Jurek J, Stafford E (2009) The economics of structured finance. J Econ Perspect 23:3–25

Crouhy MG, Jarrow RA, Turnbull SM (2008) The subprime credit crisis of 2007. J Deriv 16:81–110

Doherty NA, Kartasheva AV, Phillips RD (2009) Competition among rating agencies and information disclosure. Working Paper

Emery K, Ou S (2010) Corporate default and recovery rates, 1920–2009. Moody’s Investors Service

Erturk E (2009) Global structured finance default and transition study—1978–2008. Standard and Poor’s

European Commission (2010) Proposal for a regulation of the European parliament and of the council on amending regulation (EC) No 1060/2009 on credit rating agencies

Fons J (2002) Understanding Moody’s corporate bond ratings and rating process. Special Comment, Moody’s Investors Service

Gupta V, Parwani K (2009) Moody’s senior ratings algorithm & estimated senior ratings. Special Comment, Moody’s Investors Service

Hodrick RJ, Prescott EC (1997) Postwar U.S. business cycles: an empirical investigation. J Money, Credit, Bank 29:1–16

Holthausen RW, Leftwich RW (1986) The effects of bond rating changes on common stock prices. J Financ Econ 17:57–89

Hörner J (2002) Reputation and competition. Am Econ Rev 92:644–663

Jorion P, Zhang G (2007) Information effects of bond rating changes: the role of the rating prior to the announcement. J Fixed Income, Spring, 45–59

Jorion P, Shi C, Zhang S (2009) Tightening credit standards: fact or fiction? Rev Account Stud 14:1573–7136

Kisgen D (2009) Do firms target credit ratings or leverage levels? J Financ Quant Anal 44:1323–1344

Klein B, Leffler KB (1981) The role of market forces in assuring contractual performance. J Polit Econ 89:615–641

Konold C (1989) Informal conceptions of probability. Cogn Instr 6:59–98

Lizzeri A (1999) Information revelation and certification intermediaries. RAND J Econ 30:214–231

Löffler G (2005) Avoiding the rating bounce: why rating agencies are slow to react to new information. J Econ Behav Organ 56:365–381

Mahoney C (2002) The bond rating process: a progress report. Special comment, Moody’s Investors Service

Mathis J, McAndrews J, Rochet J-C (2009) Rating the raters: are reputation concerns powerful enough to discipline rating agencies? J Monet Econ 56:657–674

Nanda V, Yun Y (1997) Reputation and financial intermediation: an empirical investigation of the impact of IPO mispricing on underwriter market value. J Financ Intermed 6:39–63

Pedersen TM (2001) The Hodrick-Prescott filter, the Slutzky effect, and the distortionary effect of filters. J Econ Dyn Control 25:1081–1101

Penas MF, Tümer-Alkan G (2010) Bank disclosure and market assessment of financial fragility: evidence from Turkish banks’ equity prices. J Financ Serv Res 37:159–178

Strausz R (2005) Honest certification and the threat of capture. Int J Ind Organ 23:45–62

Stumpp PM, Coppola MM (2002) Moody’s analysis of US corporate rating triggers heightens need for increased disclosure. Special comment, Moody’s Investors Service

Vazza D (2009) 2008 annual global corporate default study and rating transitions. Standard and Poor’s

White LJ (2010) Markets: the credit rating agencies. J Econ Perspect 24:211–226

Yoshizawa Y (2003) Moody’s approach to rating synthetic CDOs. Special comment, Moody’s Investors Service

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

I am very grateful to an anonymous reviewer and the editor for many helpful comments, as well as to Moody’s Investors Service for providing the data.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Löffler, G. Can Market Discipline Work in the Case of Rating Agencies? Some Lessons from Moody’s Stock Price. J Financ Serv Res 43, 149–174 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-011-0128-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-011-0128-5