Abstract

This paper studies the impact of capital requirements, deposit insurance and franchise value on a bank’s capital structure. We find that properly regulated banks voluntarily choose to maintain capital in excess of the minimum required. Central to this decision is both firm franchise value and the ability of regulators to place banks in receivership stripping equity holders of firm value. These features of our model help explain both the capital structure of the large mortgage Government Sponsored Enterprises and the recent increase in risk taking through leverage by financial institutions. The insights gained from the model are useful in guiding the discussion of financial regulatory reforms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Several models (Blum and Hellwig 1995; Bolton and Freixas 2006; Peura and Keppo 2006) generate bank capital holdings in excess of capital regulation requirements as a buffer to avoid violating the regulatory constraint or to avoid high transactions costs associated with continually updating capital holdings. However, in these models, the banks’ optimal policy remains to minimize capital holdings subject to a regulatory constraint and so banks in these models are still effectively at a corner solution.

Insured deposits represent one of the lowest cost capital sources for banks and until the recent crisis most solvent banks paid almost no premium for their insurance.

Unlike the traditional moral hazard-regulatory cost models, models of banks that face principal agent problems can lead to banks that in equilibrium have an interior optimum for their capital holdings. For example, Allen et al. (2011) and Mehran and Thakor (2011) consider models where capital creates an incentive for banks to monitor loans lowering the equilibrium interest rate on those loans. Alternatively, Diamond and Rajan (2000) consider a model where the risk of bank runs force banks to use private skills to collect on loans, and holding capital protects banks against such runs but weakens the incentive for private effort.

Similarly, our model will hold the variance of the asset process fixed over time in essence assuming that banks cannot change their asset mix in response to changes in the economic environment. As with recapitalization, the illiquidity of fixed income securities markets during the recent crisis illustrates that banks may find it difficult to reduce portfolio risk during turbulent economic times.

Although this assumption allows firms to raise some capital during an economic downturn, the firms are not able to recapitalize after severe negative shocks and so face increased likelihood of involuntary closure by regulators. Further, firms never operate with negative equity, and therefore our assumption of the ability to raise equity is only for firms with positive equity.

Incorporating an insurance premium calculated as a fixed percentage of the face value of the insured deposits is straightforward and does not materially change the results discussed here.

We assume that in practice local market conditions and federal regulations impose upper bounds on firm size.

A bank’s assets are primarily composed of loans and securities. While the assumption of active trading is valid for securities, we assume that the loan component is perfectly correlated with some actively traded benchmark security. We believe this assumption is reasonable given the close linkage between loan rates and capital market rates.

In the context of corporate debt (Leland 1994; Leland and Toft 1996), the assumption Ft = 0 can be justified by considering only long maturity debt or debt that is continuously rolled over at a fixed rate or a fixed spread to a benchmark rate. The latter justification is also applicable to banks. Even though most bank deposits technically have short maturities, as long as the bank is solvent and maintains competitive pricing, it can rollover deposits at the riskless rate because depositors do not have an incentive to monitor a bank’s financial condition. For example, although demand deposits can be withdrawn at any time by the customer, in bank acquisitions, these deposits are generally viewed as a long-term, stable source of funds and hence part of the franchise value of the bank.

This simplified regulation structure is equivalent to considering a bank that only has Tier I capital and a low risk portfolio for which the book assets capital ratio is the binding constraint.

Earlier versions of this paper contained an extension that analyzed two capital thresholds: a high “warning” level and a lower insolvency level where the bank is liquidated. We found that the additional warning threshold has only a small impact on optimal leverage, even with substantial warning costs (Harding et al. 2007).

τ should be positive and β should be close to one if not greater than one.

In our model, firm value and equity value differ by the term -C/r. Thus for a fixed r, there is no difference between setting the partial derivative of the firm value equal to zero and the derivative of equity equal to -1/r.

With zero franchise value, the model contains two contingent claims: bankruptcy costs that favor equity financing and insurance benefits that favor debt financing. Both claims pay off when the firm’s assets, V, reach VB, and one term always dominates the other over all V. This result can also be seen in Eq. 10 because when τ equals 0 the derivative depends upon the sign of k, which is in turn determined by the sign of (β-1).

Unlike Elizdale and Repullo (2007), we find that a bank may choose all equity, i.e. zero debt or deposits in models without tax-advantaged debt. This difference does not arise from a fundamental difference between the models, but rather because in our model the regulator liquidation threshold is a policy parameter that can be selected.

The k > 0 condition also affects banks’ preference for portfolio risk. When this condition is met, bank value monotonically decreases with risk/variance σ, but if the condition fails, banks choose both the maximum leverage and the maximum portfolio risk allowed. A similar corner solution for variance arises in Leland (1994).

We have also examined a situation where deposit based franchise value is replaced by a more general form that depends linearly upon both total debt and total assets. Such a model continues to yield an interior optimal capital structure, but an optimal capital structure does not exist if franchise value only depends linearly on total firm assets.

In terms of other comparative statics, a decrease in r (or an increase in σ and β) leads to a higher likelihood of insolvency, ceteris paribus, and so lead the bank to select a lower coupon rate and lower leverage. The optimal coupon C* is monotonically increasing in g, and g is an increasing function of the riskless rate r (a decreasing function of σ and β), as long as β > 1-τ. This result also requires the assumption that log(1 + X) > 1/X where X = 2r/σ2. This assumption is satisfied whenever 2r/σ2 > 1, which is a fairly standard assumption in financial models.

It should be noted, however, that, ceteris paribus, a bank with β < 1 will choose a higher C* than the equivalent bank with β > 1. The difference we are talking about here is in the response of the bank to a change in franchise value. The first bank would lower its very high leverage while the second would increase its lower leverage.

Under the risk neutral probability measure, all assets have a drift equal to the riskless rate. If banks chose to commit to a debt service payment rate (as a percentage of its assets) that was in excess of the asset drift, this would imply a market value of debt in excess of the market value of assets under the risk neutral measure and the bank would be unable to raise new equity to service the debt commitment. Leverages above 1 can arise for values of β near (1-τ), but at such values g is near zero and close to the knife-edge case where an optimal coupon does not exist.

As in footnote 21, in practice, this relationship only breaks down for values of β near (1-τ).

Leverage also decreases with franchise value for reasonable parameter values when franchise value is defined more generally as a linear function of both firm debt and total firm assets.

One source of franchise value for all firms is tax-advantage debt, and we use effective tax rates as a guide for setting franchise value. Although the top marginal corporate tax rate is 40%, FDIC Call reports show that the average effective tax rate for U.S. commercial banks is 31.9%. Further, the effective tax rate for small commercial banks (assets less than $100 million) is 19.8% while the rate for large banks (assets > $1 billion) is 32.7%.

The possibility that a regulated bank might choose a leverage level that is higher than an unregulated firm without protected debt deserves some discussion. For the regulated bank that operates under the weakest capital standards, the insurance benefits net of bankruptcy costs provide an incentive for taking on more debt. It is only the risk of losing franchise value due to forced liquidation that yields an interior optimal capital ratio. As franchise values decrease, this risk becomes less important and bank leverage increases, while for the unregulated firm franchise value create an unambiguous incentive for taking on more leverage.

The book leverage levels reported in Tables I and II tend to be lower than the industry average of 90%. Focusing on β = 1.05 (roughly corresponding to a “Well Capitalized” bank standard) and ten percent asset volatility, the model predicts book leverage of 76%. There are several possible explanations for this difference. First, the overall industry average is distorted by the inclusion of large international banks. The industry average leverage for small banks (assets less than $100 million) is somewhat lower at 87%. Further, our model does not consider multiple types of debt. Deposits represent only 67% of bank assets—a figure lower than our predicted ratio. The use of other forms of debt is motivated by a number of different factors not captured in our model. For example, short-term borrowing via Fed Funds or repurchase agreements may be less costly than deposits which entail providing customer service, and subordinated debt has the advantage of being included in Tier II capital. Finally, our model does not incorporate agency cost motives for issuing debt (Jensen 1986; Jensen and Meckling 1976).

A second benefit that is often discussed is the attraction or intermediation of more capital for investment which in turn leads to greater economic growth. We do not explicitly consider this benefit because it requires value judgments concerning whether the current level of investment is too high. Further, in many macroeconomic models, the organization of financial capital does not create additional physical capital because in equilibrium investment is determined by the share of an economies production that is not consumed, i.e. savings equals investment.

An increase in the return to bank equity and the associated increase in the equilibrium risk free interest rate in response to lower capital standards are similar to the Pareto Improvement arising from imposition of interest rate limits in Hellmann et al. (2000).

Beginning in 2002, the GSEs were also subject to a risk-based capital standard. From its inception through 2007, the risk-based capital requirement was significantly lower than the statutory minimum capital requirement based on assets and MBS. Consequently the risk-based standard was never binding because the GSEs were required to meet the higher of the two standards.

OFHEO did have the authority to issue cease and desist orders. However, ordering the immediate cessation of operations would have had far-reaching economic ramifications and was consequently not a credible threat.

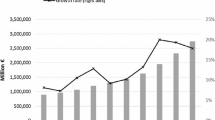

The capital shortfalls reported by Fannie Mae for 2002 and 2003 are the result of a restatement of earnings in those years. Similarly, the sharp increase in capital reported for Freddie Mac in 2002 (and the resulting above-average excess capital) is attributable to an upward restatement of earnings.

The GSE capital standard is contemporaneous and requires that capital at the end of the quarter meet the standard—even though the actual values for assets and MBS are not known with certainty until after the books are closed after the end of the quarter. This process led the institutions to target a small precautionary excess capital amount to cover unexpected fluctuations in assets and MBS.

In the late 1990’s, the GSE’s were able to readily sell preferred stock on advantageous terms and used preferred stock sales when they needed to build capital.

Data on commercial bank capital ratios is available at www2.fdic.gov/SDI.

A similar argument can be made that in 2005–2007 the rapid growth and market acceptance of “private label” mortgage-backed securities (i.e., those not guaranteed by a GSE) reduced the franchise value of the GSEs and led to increased risk-taking behavior. However, since they were already operating at their minimum capital threshold, the incentive to take more risk was reflected in their asset mix—an aspect not incorporated in our model. Also see Jaffee (2003, 2007) for discussions of the GSE’s exposure to interest rate risk and the implications of the implicit government guarantee of GSE debt.

See Kane (2009), Caprio et al. (2008), Chari et al. (2008), Cohen-Cole et al. (2008) for more general discussions of the causes of the current financial crisis. See Harding and Ross (2009) for a more specific discussion of the implications of financial models of firm capital structure for reform of financial regulation.

References

Allen F, Carletti E, Marquez R (2011) Credit market competition and capital regulation. Rev Financ Stud 24(4):983–1018

Bennett R, Unal H (2009) The cost effectiveness of the private-sector resolution of failed bank assets. FDIC Center for Financial Research Working Paper No. 2009-11

Berger A, DeYoung R, Flannery M, Lee D, Oztekin O (2008) How do large banking organizations manage their capital ratios? J Financ Serv Res 34(2/3):123–149

Besanko D, Kanatas G (1996) The regulation of bank capital: Do capital standards promote bank safety? J Financ Intermed 5(4):160–183

Blum J, Hellwig M (1995) The macroeconomic implications of capital adequacy requirements for banks. Eur Econ Rev 39(3/4):739–49

Bolton P, Freixas X (2006) Corporate finance and the monetary transmission mechanism. Rev Financ Stud 19(3):829–70

Brewer E, Kaufman G, Wall L (2008) Bank capital ratios across countries: Why do they vary? J of Financ Serv Res 34(2):177–201

Buser S, Chen A, Kane E (1981) Federal deposit insurance, regulatory policy and optimal bank capital. J Financ 36(1):51–60

Caprio G, Demirgüç-Kunt A, Kane E (2008) The 2007 meltdown in structured securitization: Searching for lessons not scapegoats. Working Paper WPS 4756, World Bank Policy Research

Chari V, Christiano L, Kehoe P (2008) Facts and myths about the financial crisis of 2008. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, Working Paper 666

Cohen-Cole E, Duygan-Bump B, Fillat J, Montoriol-Garriga J (2008) Looking behind the aggregates: A reply to “Facts and myths about the financial crisis of 2008”. Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, Working Paper QAU08-5

Cox J, Ingersoll J, Ross S (1985) An intertemporal general equilibrium model of asset prices. Econometrica 53(2):363–384

Diamond D, Rajan R (2000) A theory of bank capital. J of Financ 55(6):2431–2465

Elizdale A, Repullo R (2007) Economic and regulatory capital in banking: What is the difference? Int J Central Banking 3(3):87–117

Flannery M, Rangan K (2008) What caused the bank capital build-up of the 1990s? Rev Financ 12(2):391–429

Gale D (2004) Notes on optimal capital regulation. In: St Amant P, Wilkins C (eds) The Evolving Financial System and Public Policy, Bank of Canada, Ottawa

Gale D, Ozgur O (2005) Are bank capital ratios too high or too low? Incomplete markets and optimal capital structures. J Eur Econ Assoc 3(2/3):690–700

Genotte G, Pyle D (1991) Capital controls and bank risk. J Bank Financ 15(5):805–824

Gropp R, Heider F (2010) The determinants of bank capital structure. Rev Financ 14(4):587–622

Gueyie J, Lai V (2003) Bank moral hazard and the introduction of official deposit insurance in Canada. Int Rev Econ Financ 12(2):247–273

Harding J, Ross S (2009) Regulation of large financial institutions: Lessons from corporate finance theory. Conn Ins Law J 16(1):243–260

Harding J, Liang X, Ross S (2007) The optimal capital structure of banks: Balancing deposit insurance, capital requirements, and tax-advantaged debt. University of Connecticut Working Paper

Hellmann T, Murdock K, Stiglitz J (2000) Liberalization, moral hazard in banking, and prudential regulation: Are capital requirements enough? Amer Econ Rev 90(1):147–165

Jaffee D (2003) The interest rate risk of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. J Financ Serv Res 24(1):5–29

Jaffee D (2007) Two key issues concerning the supervision of bank safety and soundness, Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta. Econ Rev 92(1/2):114–117

Jensen M (1986) Agency costs of free cash flow, corporate finance and takeovers. Amer Econ Rev 76(2):323–329

Jensen M, Meckling W (1976) Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. J Financ Econ 3(4):305–360

Kane E (1989) The S&L insurance mess: How did it happen? Urban Institute Press, Washington, D.C

Kane E (2009) Incentive roots of the securitization crisis and its early mismanagement. Yale J Reg 26(2):101–112

Keeley M (1990) Deposit insurance, risk, and market power in banking. Amer Econ Rev 80(5):1183–1200

Leland H (1994) Corporate debt value, bond covenants, and optimal capital structure. J Financ 49(4):1213–1252

Leland H, Toft K (1996) Optimal capital structure, endogenous bankruptcy and the term structure of credit spreads. J Financ 51(3):987–1019

Marcus A (1984) Deregulation and bank financial policy. J Bank Financ 8(4):557–565

Marshall D, Prescott E (2000) Bank capital regulation with and without state-contingent penalties. Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, Working Paper WP-00-01

Mehran H, Thakor A (2011) Bank capital and value in the cross-section. Rev Financ Stud 24(4):1019–1067

Merton R (1978) On the cost of deposit insurance when there are surveillance costs. J Bus 51(3):439–452

Miller M (1977) Debt and taxes. J Financ 32(2):261–275

Peura S, Keppo J (2006) Optimal bank capital with costly recapitalization. J Bus 79(4):2163–201

Repullo R (2004) Capital requirements, market power, and risk-taking in banking. J Financ Intermed 13(1):156–82

Rochet J (1992) Capital requirements and the behavior of commercial banks. Eur Econ Rev 36(5):1137–1170

Van den Heuvel S (2008) The welfare cost of bank capital requirements. J Monetary Econ 55(2):298–320

Acknowledgements

Disclaimers

We received valuable comments from seminar participants at the Federal Reserve Banks of Boston, Philadelphia and St. Louis, the Haas School of Business at the University of California-Berkeley, the University of Connecticut and FannieMae. We are especially appreciative for our detailed conversations about the paper with Dwight Jaffee and Nancy Wallace, as well as for detailed and valuable comments from the editor and anonymous referees. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of State Street Corporation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Harding, J.P., Liang, X. & Ross, S.L. Bank Capital Requirements, Capital Structure and Regulation. J Financ Serv Res 43, 127–148 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-011-0127-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-011-0127-6