Abstract

Choice lists with random incentives are widely used for preference elicitation. It is commonly assumed that subjects choose the same option in each question as they would have if it were the only question, but recent findings challenge this assumption. We conduct a large sample experiment varying incentives and presentation independently, and examine choices both near and away from certainty. We consistently find more risk taking when a choice between a safe prize and a risky lottery is embedded in a choice list than when it is presented on its own. This difference remains when we inform subjects of the paid choice in advance, implying that isolation fails not because of the random incentives scheme, but simply because the choice appears in a list together with others. We conjecture that subjects are uncertain about their preferences, reduce this uncertainty through considering the choices that confront them, and make cautious decisions in the interim. Other conditions and non-choice data support this interpretation. Our results open up the possibility that preferences inferred from choice lists offer a better indication of informed preferences than preferences inferred from single choices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For example, in problem 3 in Tversky and Kahneman (1981), 84% of subjects choose a certain gain of $240 over a 25% chance of $1000 in their first decision, and 87% of subjects choose a 75% chance of losing $1000 over a certain loss of $750 in their second decision. Not a single subject makes the combined modal choice when it is offered as part of a single decision problem.

These papers (and ours) use a between-subjects design to infer an inconsistency in how a subject would choose in a given question across different experimental conditions that vary incentives and presentation. Other papers that use a within-subjects design find inconsistency in how the same subject chooses when responding to the same question on multiple occasions (Hey and Orme 1994; Loomes and Sugden 1998; Agranov and Ortoleva 2017).

Similar restrictions were used in Berinsky et al. (2012) and Freeman et al. (in press) Mturk workers based in the US have to provide Amazon with their taxpayer identification information, which is then verified. This effectively ensures that each worker has only one account.

There were 11 dropouts (4 R-list subjects, 3 K-list subjects, and 4 SC subjects).

In line with Freeman et al. (in press), DF thought that isolation fails because of a preference for certainty, and that we would therefore find support for Hypotheses 2, 5 and 6. GM was sceptical about subjects? ability to think through the implications of RIS, and instead thought that it is the difference in presentation that matters, including the order of questions in the list. GM expected to find support for Hypotheses 3, 4 and 10.

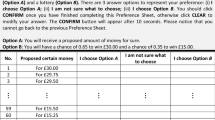

Pilot sessions only included variations on R-list Descending and SC. 18 of 32 list subjects (56.25%) chose the risky option in Q85 as compared with 7 out of 30 single choice subjects (23.33%).

Q85 is the only incentivized question in K-list conditions. The other questions must be answered, but subjects have no monetary incentive to reveal their preferences.

We limit Hypothesis 4 to R-lists, because in K-lists only one question is incentivised.

See Freeman et al. (in press, Sect. 4) for a more formal version of this argument, building on Karni and Safra (1987).

Since other presentation effects do have testable implications for Q85, this makes it possible for us to test for their presence independently of our test for middle bias.

Loomes and Pogrebna (2014) find evidence of such an effect.

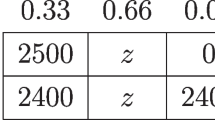

For example, a subject from whom the probability equivalent of $1 with 100% chance is $1.40 with 82% chooses the risky option in Q100, Q95, Q90 and Q85, and the safe option in Q80, Q75 and Q70.

According to Tversky et al. (1988), ‘there is no obvious reason that probability is more prominent than money or vice versa.’

The most statistically significant individual control was the self-reported tolerance for risks. Whether it improves the accuracy of our estimates depends on the extent to which it is a useful measure of a risk taking personality. Encouragingly, it did not differ meaningfully across conditions (\(p=0.21\)), even when actual risk taking was significantly different.

As in other experiments that use choice lists, a small proportion of subjects in list conditions violated monotonicity (Online Appendix B). For example, a subject may choose the risky option in Q85 and the safe one in Q90. Some experimenters consider such subjects to be ‘noise subjects’, and drop them from their analysis. Since we can only identify such subjects in list conditions, it was not possible to drop them without introducing bias in our comparisons between list and single choice conditions.

The p value in the test comparing the K-list Scrambled condition with the corresponding R-list condition has a marginally smaller p value of 0.13, but the conventional statistical significance threshold should be adjusted down to allow for the separate testing of the three order variants.

In an ordered probit regression with the total number of risky choices as the dependent variable, the lowest p value is \(p=0.397\) (between R-list Ascending and R-list Scrambled). In a question specific comparison, the smallest p value is \(p=0.03\) (in Q70 between K-list Descending and K-list Scrambled).

In a contemporaneous experiment, Brown and Healy (2018) compare the impact of different mechanisms on a choice between two risky lotteries (a 50% chance of $10 and a 50% chance of $5 vs. a 70% chance of $15). Like us, they find no difference in risk taking between single choices and lists with RIS incentives. They do, however, find a statistically significant (\(p=0.041\)) difference between their analogues of R-lists and K-lists.

Such a tendency is captured in the cautious expected utility model of Cerreia-Vioglio et al. (2015), which assumes that each preference relation under consideration satisfies expected utility. The multiple weighting model of Dean and Ortoleva (2016) is similar in spirit, but assumes that each preference relation under consideration satisfies rank-dependent utility with a common utility-for-money function. Either model could be applied to obtain the results here.

Since the set of preference relations is finite, the preference narrowing process must converge. Convergence to a set consisting of more than one ‘reasonable’ preference relation is possible, but the cautious decision criterion will map it to one effective preference relation.

If we were not concerned with subjects having a preference for consistency, we could use a simpler two screen design, consisting of a choice list followed by a single choice. In this simpler design, however, the prediction of the preference narrowing model cannot be separated from that of a preference for consistency.

References

Agranov, M., & Ortoleva, P. (2017). Stochastic choice and preferences for randomization. Journal of Political Economy, 125(1), 40–68.

Andersen, S., Harrison, G., Lau, M., & Rutström, E. (2006). Elicitation using multiple price list formats. Experimental Economics, 9(4), 383–405.

Ariely, D., Loewenstein, G., & Prelec, D. (2003). Coherent arbitrariness: Stable demand curves without stable preferences. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(1), 73–105.

Battalio, R., Kagel, J., & Jiranyakul, K. (1990). Testing between alternative models of choice under uncertainty: Some initial results. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 3(1), 25–50.

Beattie, J., & Loomes, G. (1997). The impact of incentives upon risky choice experiments. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 14(2), 155–168.

Beauchamp, J. P., Benjamin, D. J., Chabris, C. F., & Laibson, D. I . (2015). Controlling for the compromise effect debiases estimates of risk preference parameters. Technical report, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Berg, J. E., Dickhaut, J. W., & Rietz, T. A. (2010). Preference reversals: The impact of truth-revealing monetary incentives. Games and Economic Behavior, 68(2), 443–468.

Berinsky, A. J., Huber, G. A., & Lenz, G. S. (2012). Evaluating online labor markets for experimental research: Amazon.com’s mechanical turk. Political Analysis, 20(3), 351–368.

Brown, A. L., & Healy, P. J. (2018). Separated decisions. European Economic Review, 101, 20–34.

Butler, D., & Loomes, G. (2007). Imprecision as an account of the preference reversal phenomenon. American Economic Review, 97(1), 277–297.

Colin, C. F. (1989). An experimental test of several generalized utility theories. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 2(1), 61–104.

Castillo, M., & Eil, D. (2014). Tariffing the multiple price list: Imperceptive preferences and the reversing of the common ratio effect. Working paper.

Cerreia-Vioglio, S., Dillenberger, D., & Ortoleva, P. (2015). Cautious expected utility and the certainty effect. Econometrica, 83(2), 693–728.

Cox, J. C., Sadiraj, V., & Schmidt, U. (2014). Asymmetrically dominated choice problems, the isolation hypothesis and random incentive mechanisms. PloS ONE, 9(3), e90742.

Cox, J. C., Sadiraj, V., & Schmidt, U. (2015). Paradoxes and mechanisms for choice under risk. Experimental Economics, 18(2), 215–250.

Cubitt, R. P., Munro, A., & Starmer, C. (2004). Testing explanations of preference reversal. Economic Journal, 114(497), 709–726.

Cubitt, R. P., Starmer, C., & Sugden, R. (1998). On the validity of the random lottery incentive system. Experimental Economics, 1(2), 115–131.

Dean, M., & Ortoleva, P. (2016). Allais, ellsberg, and preferences for hedging. Theoretical Economics, 12(1), 317–424.

Difallah, D., Filatova, E., & Ipeirotis, P. (2018). Demographics and dynamics of mechanical turk workers. In Proceedings of the eleventh ACM international conference on web search and data mining. ACM, pp. 135–143.

Freeman, D., Halevy, Y., & Kneeland, T. (in press). Eliciting risk preferences using choice lists. Quantitative Economics. https://www.econometricsociety.org/publications/econometrica/about/journal-news/2018/05/01/new-papers-posted-quantitative-economics.

Grether, D., & Plott, C. (1979). Economic theory of choice and the preference reversal phenomenon. American Economic Review, 69(4), 623–638.

Harrison, G., & Swarthout, J. (2014). Experimental payment protocols and the bipolar behaviorist. Theory and Decision, 77(3), 423–438.

Hey, J. D., & Orme, C. (1994). Investigating generalizations of expected utility theory using experimental data. Econometrica, 62, 1291–1326.

Hey, J. D., & Lee, J. (2005). Do subjects separate (or are they sophisticated)? Experimental Economics, 8(3), 233–265.

Hey, J. D., Morone, Andrea, & Schmidt, U. (2009). Noise and bias in eliciting preferences. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 39(3), 213–235.

Holt, C. (1986). Preference reversals and the independence axiom. American Economic Review, 76(3), 508–515.

Holt, C., & Laury, S. (2002). Risk aversion and incentive effects. American Economic Review, 92(5), 1644–1655.

Horton, J., Rand, D., & Zeckhauser, R. (2011). The online laboratory: Conducting experiments in a real labor market. Experimental Economics, 14(3), 399–425.

Huber, J., Payne, J. W., & Puto, C. (1982). Adding asymmetrically dominated alternatives: Violations of regularity and the similarity hypothesis. Journal of Consumer Research, 9(1), 90–98.

Karni, E., & Safra, Z. (1987). “Preference reversal” and the observability of preferences by experimental methods. Econometrica, 55(3), 675–685.

Lévy-Garboua, L., Maafi, H., Masclet, D., & Terracol, A. (2012). Risk aversion and framing effects. Experimental Economics, 15(1), 128–144.

Lichtenstein, S., & Slovic, P. (1971). Reversal of preference between bids and choices in gambling decisions. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 89(1), 46–55.

Lichtenstein, S., & Slovic, P. (2006). The construction of preference. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Loomes, G., & Pogrebna, G. (2014). Measuring individual risk attitudes when preferences are imprecise. Economic Journal, 124(576), 569–593.

Loomes, G., & Sugden, R. (1998). Testing different stochastic specifications of risky choice. Economica, 65(260), 581–598.

Mason, W., & Suri, S. (2011). Conducting behavioral research on amazon’s mechanical turk. Behavior Research Methods, 44(1), 1–23.

Ok, E. A. (2002). Utility representation of an incomplete preference relation. Journal of Economic Theory, 104(2), 429–449.

Paolacci, G., Chandler, J., & Ipeirotis, P. (2010). Running experiments on amazon mechanical turk. Judgment and Decision Making, 5(5), 411–419.

Plott, C. (1996). Rational individual behaviour in markets and social choice processes. In K. Arrow, E. Colombatto, M. Perlman, & C. Schmidt (Eds.), The rational foundations of economic behaviour (pp. 225–250). Basingstoke: Macmillan Press.

Rabin, M., & Weizsäcker, G. (2009). Narrow bracketing and dominated choices. American Economic Review, 99(4), 1508–1543.

Read, D., Loewenstein, G., & Rabin, M. (1999). Choice bracketing. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 19(1–3), 171–197.

Sprenger, C. (2015). An endowment effect for risk: Experimental tests of stochastic reference points. Journal of Political Economy, 123(6), 1456–1499.

Starmer, C., & Sugden, R. (1991). Does the random-lottery incentive system elicit true preferences? An experimental investigation. American Economic Review, 81(4), 971–978.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1981). The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice. Science, 211(4481), 453–458.

Tversky, A., Sattath, S., & Slovic, P. (1988). Contingent weighting in judgment and choice. Psychological Review, 95(3), 371.

Tversky, A., Slovic, P., & Kahneman, D. (1990). The causes of preference reversal. American Economic Review, 80(1), 204–217.

Wilcox, N. T. (2008). Stochastic models for binary discrete choice under risk: A critical primer and econometric comparison. In J. C. Cox & G. W. Harrison (Eds.), Risk aversion in experiments (pp. 197–292). Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Wu, G. (1994). An empirical test of ordinal independence. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 9(1), 39–60.

Acknowledgements

We thank the editor, referees, and seminar and conference audiences for comments that improved the paper. Funding for the experiment was provided by the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research (CIFAR).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Freeman, D.J., Mayraz, G. Why choice lists increase risk taking. Exp Econ 22, 131–154 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-018-9586-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-018-9586-z