Abstract

Sequential multi-battle contests are predicted to induce lower expenditure than simultaneous contests. This prediction is a result of a “New Hampshire Effect”—a strategic advantage created by the winner of the first battle. Although our laboratory study provides evidence for the New Hampshire Effect, we find that sequential contests generate significantly higher (not lower) expenditure than simultaneous contests. This is mainly because in sequential contests, there is significant over-expenditure in all battles. We suggest sunk cost fallacy and utility of winning as two complementary explanations for this behavior and provide supporting evidence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Just as candidates who do poorly in the New Hampshire primary frequently drop out, the lesser-known, underfunded candidates who do well in the primary suddenly become serious contenders to win the party nomination, garnering tremendous momentum both in terms of media coverage and campaign funding. In 1992, Bill Clinton, a little known governor of Arkansas did surprising well, and was labeled the “Comeback Kid” by the national media. In 2000, John McCain emerged as George Bush’s principal challenger only after an upset victory in New Hampshire, and a similar comeback was made by John Kerry in the 2004 primary.

In a multi-candidate race, even a second-place finish in New Hampshire primary increases a candidate’s final vote by 17.2% (Mayer 2004).

The total economic impact of 2000 primary on New Hampshire’s economy was estimated to be $264 million. The state also receives a diverse array of ‘special policy concessions’ as a result of its privileged position in the presidential nomination process (Busch and Mayer 2004). Originally held in March, the date of the New Hampshire primary has been moved up repeatedly to maintain its status as first (a tradition since 1920). In fact, the state law requires that its primary must be the first in the nation.

Our experiment compares two extreme benchmarks: a completely sequential contest to a completely simultaneous contest. Present day primary system, however, has a mixed temporal structure. The nomination process starts with a series of sequential elections held in various states (Iowa caucus, New Hampshire primary, etc.) followed by days such as “Super Tuesday.” Klumpp and Polborn (2006) state that the results of a completely sequential contest can apply to a mixed temporal contest, as long as the latter begins with at least a few sequential battles.

The contest model is complementary to the voters’ participation model (Morton and Williams 1999; Battaglini et al. 2007). In the voters’ participation model the probability of winning an electoral district by a candidate depends on the number of votes received, while in the contest model such a probability depends on the relative campaign expenditure by each candidate in that district. The complementarity between the two models arises because one of the reasons for the New Hampshire Effect that is commonly discussed in political science is information aggregation, which is implicit in voting models. For instance, Morton and Williams (1999) compare sequential and simultaneous voting and find that in sequential voting later voters use early outcomes to infer information about asymmetric candidates, and thus make better informed choices that reflect their true preferences. Battaglini et al. (2007) find that sequential voting aggregates information better than simultaneous voting and is more efficient in some information environments, but sequential voting is inequitable because early voters bear more participation costs. By assuming that both candidates are symmetric and by abstracting from costly voter participation decision, we are able to isolate how candidates’ relative expenditure alone determines the likelihood of winning current and future electoral districts. That is, we examine the New Hampshire Effect resulting solely from candidates’ campaign expenditure decisions.

One could also argue that the original formulation of a Colonel Blotto game by Borel (1921) is a starting point of the multi-battle contest literature.

Building on these models, subsequent papers investigated the ramification of various factors such as the sequence ordering of decisions, number of battles, asymmetry between players, effect of carryover, effect of uncertainty, the impact of discount factor and intermediate prizes (Harris and Vickers 1985, 1987; Leininger 1991; Baik and Lee 2000; Szentes and Rosenthal 2003; Roberson 2006; Kvasov 2007; Konrad and Kovenock 2009).

The solution to this game can be found in Friedman (1958).

In the sequential contest, the total expected expenditure by both players in battle 1 is 32.8; in battle 2 is 18.8; and since battle 3 is likely to occur with probability 0.25, the unconditional expected expenditure in battle 3 is 25.

48% of our subjects identified as males and 52% as females. The average age of the participants was 19.63 and ranged between 18 and 28. More than 60% of the subjects were sophomores or freshmen and about 70% were majoring in business and economics.

Subjects also made 15 choices in simple lotteries, similar to Holt and Laury (2002), at the beginning of the experiment. These were used to elicit their risk aversion preferences, and subjects were paid for one randomly selected choice. We did not find any interesting patterns or correlations between risk attitudes and behavior in contests. So, we omit any discussion from the article.

100 francs is substantially higher than the highest possible equilibrium bid, but we decided not to constrain individual bidding to be consistent with the theoretical model which assumes no budget constraints. Additionally, we wanted to avoid potential unintended behavioral consequences since enforcing even non-binding budget constraints can unexpectedly affect subjects’ behavior (Price and Sheremeta 2011; Sheremeta 2011).

We chose to select only 2 periods for payment in order to avoid intra-experimental income effects (McKee 1989). In addition, subjects were paid for their lottery choice from the risk elicitation procedure.

We have checked the robustness of these results by estimating a mixed-effects panel model for each treatment (see Table B1 in Appendix B). We have 1440 observations for each treatment (6 sessions × 12 subjects × 20 periods). The dependent variable in the regression is the total expenditure and the independent variables are a constant and a period trend. The model included a mixed-effects error structure with a 3-way nested model (observations nested within a session and then within a subject) to account for the multiple decisions made by each subject and random re-matching within a session. A standard Wald test, conducted on estimates of regression models, shows that expenditure in the sequential contest is significantly higher than predicted (p value < 0.01) and for the simultaneous contest it is not different from the prediction (p value = 0.60). Hypothesis testing with a few clusters (sessions) can result in over-rejection of the null hypothesis. To address this concern, we also conducted regressions based on Cameron et al. (2008) wild cluster approach. The results remain the same—expenditure in the sequential contest is significantly higher than predicted and for the simultaneous contest it is not different from the prediction.

See Table B1 in Appendix B.

Mixed-effects panel regressions collaborate the results of the non-parametric statistical tests (see Table B2 in Appendix B). In estimating these regressions, we used total expenditure as the dependent variable and a treatment dummy-variable, a period trend, and a constant as the independent variables. Regressions based on Cameron et al. (2008) wild cluster approach produce similar results.

A mixed-effects panel regression collaborates the results of the non-parametric statistical tests (see Table B3 in Appendix B). In estimating this regression, we used a battle 2 expenditure as the dependent variable and a dummy-variable for winning battle 1, a period trend, and a constant as the independent variables. A regression based on Cameron et al. (2008) wild cluster approach produces similar results.

The non-parametric statistical tests are also corroborated by mixed-effect panel regressions (see Table B4 in Appendix B). Regressions based on Cameron et al. (2008) wild cluster approach produce similar results.

See Table B4 in Appendix B.

Explanations for over-expenditure in single-battle contests include non-monetary utility of winning (Sheremeta 2010a, b; Cason et al. 2012, 2017, 2018), mistakes (Sheremeta 2011), misperception of probabilities (Shupp et al. 2013; Chowdhury et al. 2014), evolutionary bias (Mago et al. 2016), and impulsivity (Sheremeta 2016).

This conclusion comes from estimating a mixed-effect panel regression.

The non-parametric statistical tests are also collaborated by mixed-effect panel regressions (see Table B5 in Appendix B). In estimating these regressions, we used a battle 2 expenditure as the dependent variable and a treatment dummy-variable, a period trend, and a constant as the independent variables. Regressions based on Cameron et al. (2008) wild cluster approach produce similar results.

See Table B5 in Appendix B.

As evidenced in the prior discussion, sunk cost fallacy cannot explain all the deviations from the theory. Even in the modified sessions, expenditure in battle 2 remains significantly higher relative to the theoretical predictions for both winner and loser of battle 1. Also, the sunk cost fallacy cannot explain the fact that battle 1 loser (who presumably spent less resources in battle 1, and should not be subject to sunk cost fallacy as much as battle 1 winner) does not give up in battle 2.

That is, there is no allocation bias such as that observed in Colonel Blotto games (Chowdhury et al. 2013), where players who read and write from left to right horizontally in their native language tend to allocate greater expenditure to the battles on the left.

It is important to emphasize, however, that the “guerilla warfare” strategy is not an equilibrium strategy. In fact, in the context of a lottery contest success function, the only equilibrium is to allocate resources uniformly across all battles (Klumpp and Polborn 2006; Kovenock et al. 2010; Kovenock and Roberson 2012).

References

Altmann, S., Falk, A., & Wibral, M. (2012). Promotions and incentives: The case of multistage elimination tournaments. Journal of Labor Economics, 30, 149–174.

Amaldoss, W., & Rapoport, A. (2009). Excessive expenditure in two-stage contests: Theory and experimental evidence. In F. Columbus (Ed.), Game theory: Strategies, equilibria, and theorems. Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science Publishers.

Amegashie, J. A., Cadsby, C. B., & Song, Y. (2007). Competitive burnout: Theory and experimental evidence. Games and Economic Behavior, 59, 213–239.

Arad, A. (2012). The Tennis Coach problem: A game-theoretic and experimental study. The B.E. Journal of Theoretical Economics, 12, 10.

Arad, A., & Rubinstein, A. (2012). Multi-dimensional iterative reasoning in action: The case of the Colonel Blotto game. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 84, 571–585.

Augenblick, N. (2016). The sunk-cost fallacy in penny auctions. Review of Economic Studies, 83, 58–86.

Avrahami, J., & Kareev, Y. (2009). Do the weak stand a chance? Distribution of resources in a competitive environment. Cognitive Science, 33, 940–950.

Avrahami, J., Kareev, Y., Todd, P.M., & Silverman, B. (2014). Allocation of resources in asymmetric competitions: How do the weak maintain a chance of winning? Journal of Economic Psychology, 42, 161–174.

Baik, K., & Lee, S. (2000). Two-stage rent-seeking contests with carryovers. Public Choice, 103, 285–296.

Baliga, S., & Ely, J. C. (2011). Mnemonomics: The sunk cost fallacy as a memory kludge. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics, 3, 35–67.

Battaglini, M., Morton, R. B., & Palfrey, T. R. (2007). Efficiency, equity and timing of voting mechanisms. American Political Science Review, 101, 409–424.

Borel, E. (1921). La theorie du jeu les equations integrales a noyau symetrique. Comptes Rendus del Academie. 173, 1304–1308; English translation by Savage, L. (1953). The theory of play and integral equations with skew symmetric kernels. Econometrica, 21, 97–100.

Busch, A., & Mayer, W. (2004). The front-loading problem. In W. Mayer (Ed.), The making of the presidential candidate (pp. 83–132). USA: Rowman and Littlefied Publishers Inc.

Callander, S. (2007). Bandwagons and momentum in sequential voting. Review of Economic Studies, 74, 653–684.

Cameron, A. C., Gelbach, J. B., & Miller, D. L. (2008). Bootstrap-based improvements for inference with clustered errors. Review of Economics and Statistics, 90, 414–427.

Cason, T. N., Masters, W. A. & Sheremeta, R. M. (2018). Winner-take-all and proportional-prize contests: Theory and experimental results. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization. (forthcoming).

Cason, T. N., Sheremeta, R. M., & Zhang, J. (2012). Communication and efficiency in competitive coordination games. Games and Economic Behavior, 76, 26–43.

Cason, T. N., Sheremeta, R. M., & Zhang, J. (2017). Asymmetric and endogenous within-group communication in competitive coordination games. Experimental Economics, 20, 946–972.

Chowdhury, S. M., Kovenock, D., & Sheremeta, R. M. (2013). An experimental investigation of Colonel Blotto games. Economic Theory, 52, 833–861.

Chowdhury, S. M., Sheremeta, R. M., & Turocy, T. L. (2014). Overbidding and overspreading in rent-seeking experiments: Cost structure and prize allocation rules. Games and Economic Behavior, 87, 224–238.

Clark, D. J., & Konrad, K. A. (2007). Asymmetric conflict weakest link against best shot. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 51, 457–469.

Clark, D. J., & Konrad, K. A. (2008). Fragmented property rights and incentives for R&D. Management Science, 54, 969–981.

Cox, J. C., Smith, V. L., & Walker, J. M. (1988). Theory and individual behavior of first-price auctions. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 1, 61–99.

Davis, D., & Reilly, R. (1998). Do too many cooks spoil the stew? An experimental analysis of rent-seeking and the role of a strategic buyer. Public Choice, 95, 89–115.

Dechenaux, E., Kovenock, D., & Sheremeta, R. M. (2015). A survey of experimental research on contests, all-pay auctions and tournaments. Experimental Economics, 18, 609–669.

Deck, C., & Sheremeta, R. M. (2012). Fight or flight? Defending against sequential attacks in the Game of Siege. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 56, 1069–1088.

Deck, C. & Sheremeta, R. M. (2016). Tug-of-war in the laboratory. Working paper.

Duffy, J., & Matros, A. (2015). Stochastic asymmetric Blotto games: Some new results. Economics Letters, 134, 4–8.

Feigenbaum, J. J., & Shelton, C. A. (2013). The vicious cycle: Fundraising and perceived viability in US presidential primaries. Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 8, 1–40.

Fischbacher, U. (2007). z-Tree: Zurich toolbox for ready-made economic experiments. Experimental Economics, 10, 171–178.

Friedman, L. (1958). Game-theory models in the allocation of advertising expenditure. Operations Research, 6, 699–709.

Friedman, D., Pommerenke, K., Lukose, R., Milam, G., & Huberman, B. (2007). Searching for the sunk cost fallacy. Experimental Economics, 10, 79–104.

Fudenberg, D., Gilbert, R., Stiglitz, J., & Tirole, J. (1983). Preemption, leapfrogging and competition in patent races. European Economic Review, 22, 3–31.

Gelder, A., & Kovenock, D. (2017). Dynamic behavior and player types in majoritarian multi-battle contests. Games and Economic Behavior, 104, 444–455.

Goeree, J. K., Holt, C. A., & Palfrey, T. R. (2002). Quantal response equilibrium and overbidding in private-value auctions. Journal of Economic Theory, 104, 247–272.

Harris, C., & Vickers, J. (1985). Perfect equilibrium in a model of a race. Review of Economic Studies, 52, 193–209.

Harris, C., & Vickers, J. (1987). Racing with uncertainty. Review of Economic Studies, 54, 1–21.

Hausken, K. (2008). Strategic defense and attack for series and parallel reliability systems. European Journal of Operational Research, 186, 856–881.

Höchtl, W., Kerschbamer, R., Stracke, R., & Sunde, U. (2015). Incentives vs. selection in promotion tournaments: Can a designer kill two birds with one stone? Managerial and Decision Economics, 36, 275–285.

Holt, C. A., Kydd, A., Razzolini, L., & Sheremeta, R. (2016). The paradox of misaligned profiling theory and experimental evidence. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 60, 482–500.

Holt, C. A., & Laury, S. K. (2002). Risk aversion and incentive effects. American Economic Review, 92, 1644–1655.

Hortala-Vallve, R., & Llorente-Saguer, A. (2010). A simple mechanism for resolving conflict. Games and Economic Behavior, 70, 375–391.

Just, D. R., & Wansink, B. (2011). The flat-rate pricing paradox: Conflicting effects of “all-you-can-eat” buffet pricing. Review of Economics and Statistics, 93, 193–200.

Klumpp, T., & Polborn, M. K. (2006). Primaries and the New Hampshire effect. Journal of Public Economics, 90, 1073–1114.

Konrad, K. A., & Kovenock, D. (2009). Multi-battle contests. Games Economic Behavior, 66, 256–274.

Kovenock, D., & Roberson, B. (2012). Conflicts with multiple battlefields. In M. R. Garfinkel & S. Skaperdas (Eds.), Oxford handbook of the economics of peace and conflict (pp. 503–531). New York: Oxford University Press.

Kovenock, D., Roberson, B. & Sheremeta, R. M. (2010). The attack and defense of weakest-link networks. Working paper.

Kvasov, D. (2007). Contests with limited resources. Journal of Economic Theory, 136, 738–748.

Leininger, W. (1991). Patent competition, rent dissipation, and the persistence of monopoly: The role of research budgets. Journal of Economic Theory, 53, 146–172.

Mago, S. D., Savikhin, A. C., & Sheremeta, R. M. (2016). Facing your opponents: Social identification and information feedback in contests. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 60, 459–481.

Mago, S. D., & Sheremeta, R. M. (2017). Multi-battle contests: An experimental study. Southern Economic Journal, 84, 407–425.

Mago, S. D., Sheremeta, R. M., & Yates, A. (2013). Best-of-three contest experiments: Strategic versus psychological momentum. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 31, 287–296.

Mayer, W. (2004). The basic dynamics of contemporary nomination process. In W. Mayer (Ed.), The making of the presidential candidate (pp. 83–132). Lanham, MA: Rowman and Littlefied Publishers Inc.

McKee, M. (1989). Intra-experimental income effects and risk aversion. Economic Letters, 30, 109–115.

Montero, M., Possajennikov, A., Sefton, M., & Turocy, T. L. (2016). Majoritarian Blotto contests with asymmetric battlefields: An experiment on Apex games. Economic Theory, 61, 55–89.

Morton, R. B., & Williams, K. C. (1999). Information asymmetries and simultaneous versus sequential voting. American Political Science Review, 93, 51–67.

Morton, R. B., & Williams, K. C. (2000). Learning by voting: Sequential choices in presidential primaries and other elections. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Parco, J., Rapoport, A., & Amaldoss, W. (2005). Two-stage contests with budget constraints: An experimental study. Journal of Mathematical Psychology, 49, 320–338.

Price, C. R., & Sheremeta, R. M. (2011). Endowment effects in contests. Economics Letters, 111, 217–219.

Price, C. R., & Sheremeta, R. M. (2015). Endowment origin, demographic effects and individual preferences in contests. Journal of Economics and Management Strategy, 24, 597–619.

Roberson, B. (2006). The Colonel Blotto game. Economic Theory, 29, 1–24.

Ryvkin, D. (2011). Fatigue in dynamic tournaments. Journal of Economics and Management Strategy, 20, 1011–1041.

Schmitt, P., Shupp, R., Swope, K., & Cadigan, J. (2004). Multi-period rent-seeking contests with carryover: Theory and experimental evidence. Economics of Governance, 10, 247–259.

Sheremeta, R. M. (2010a). Expenditures and information disclosure in two-stage political contests. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 54, 771–798.

Sheremeta, R. M. (2010b). Experimental comparison of multi-stage and one-stage contests. Games and Economic Behavior, 68, 731–747.

Sheremeta, R. M. (2011). Contest design: An experimental investigation. Economic Inquiry, 49, 573–590.

Sheremeta, R. M. (2013). Overbidding and heterogeneous behavior in contest experiments. Journal of Economic Surveys, 27, 491–514.

Sheremeta, R. M. (2015). Behavioral dimensions of contests. In R. D. Congleton & A. L. Hillman (Eds.), Companion to the political economy of rent seeking (pp. 150–164). London: Edward Elgar.

Sheremeta, R. M. (2016). Impulsive behavior in competition: Testing theories of overbidding in rent-seeking contests. Working paper.

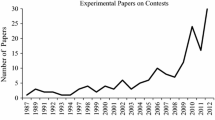

Sheremeta, R. M. (2017). Experimental research on contests. Working paper.

Sheremeta, R. M., & Zhang, J. (2010). Can groups solve the problem of over-bidding in contests? Social Choice and Welfare, 35, 175–197.

Shupp, R., Sheremeta, R. M., Schmidt, D., & Walker, J. (2013). Resource allocation contests: Experimental evidence. Journal of Economic Psychology, 39, 257–267.

Snyder, J. (1989). Election goals and the allocation of campaign resources. Econometrica, 57, 630–660.

Staw, B. M. (1976). Knee-deep in the big muddy: A study of escalating commitment to a chosen course of action. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 16, 27–44.

Szentes, B., & Rosenthal, R. W. (2003). Beyond chopsticks: Symmetric equilibria in majority auction games. Games and Economic Behavior, 45, 278–295.

Tullock, G. (1980). Efficient rent seeking. In J. M. Buchanan, R. D. Tollison, & G. Tullock (Eds.), Toward a theory of the rent-seeking society (pp. 97–112). College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press.

Zizzo, D. J. (2002). Racing with uncertainty: A patent race experiment. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 20, 877–902.

Acknowledgements

We thank David Cooper, the Editor of this journal, and two anonymous referees for their valuable suggestions. We have benefitted from the helpful comments of Tim Cason, Sera Linardi, Vai-Lam Mui, Andrew Healy, James Konow, Rebecca Morton, Tim Shields, Stergios Skaperdas, Jonathan Wight, seminar participants at Loyola Marymount University, University of California Irvine, University of Richmond and participants at the International Economic Science Association Conference in Copenhagen, the Virginia Association for Economists Meeting, and the Pittsburgh Behavioral Models of Politics Conference for helpful comments. University of Richmond provided funds for conducting the experiments. The usual disclaimers apply.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mago, S.D., Sheremeta, R.M. New Hampshire Effect: behavior in sequential and simultaneous multi-battle contests. Exp Econ 22, 325–349 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-018-9569-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-018-9569-0