Abstract

It is still an open question when groups perform better than individuals in intellective tasks. We report that in an Acquiring a Company game, what prevailed when there was disagreement among group members was the median proposal and not the best proposal. This aggregation rule explains why groups underperformed with respect to a “truth wins” benchmark and why they performed better than individuals deciding in isolation in a simple version of the task but worse in the more difficult version. Implications are drawn on when to employ groups rather than individuals in decision making.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For an excellent literature review comparing group and individual decision making, see Charness and Sutter (2012).

The term “Winner’s curse” refers to the irrational bidding behavior in common value auctions, consistently observed in the lab, where bidders often systemically overbid, resulting in an expected loss. Field evidence about overbidding has also been accumulated for a variety of similar economic situations, from mineral right auctions, eBay auctions, to baseball’s free agency market, to IPOs pricing and to corporate takeovers (e.g., Bajari and Hortacsu 2003).

This complements to previous social psychology literature arguing that different performance outcomes are a function of inherently different processes (Brodbeck et al. 2007; De Dreu et al. 2008). Brodbeck et al. (2007) propose a theoretical model that explains how the interaction between asymmetries in information distribution prior to group decision making and asymmetries in information processing during group decision making affects group performance. De Dreu et al. (2008) theorize that group performance is a function of social motivation, epistemic motivation and their interaction. When decision urgency is low, group outcome benefits from prosocial motivation coupled with high levels of epistemic motivation. When groups face emergency situations, groups perform better when prosocial motivation is paired with low levels of epistemic motivation.

The psychological literature on group versus individual decision-making distinguishes between judgmental and intellective tasks (Laughlin 1980). A judgmental task involves problems where there is no obvious “correct” action and individuals may legitimately differ on their choices because of their values or preferences. In contrast, an intellective task has a “correct” solution; sometimes this solution is difficult to discover and sometimes it is easy to discover and demonstrate to others.

To make the decisional process more comparable across treatments, all treatments followed the same random draw procedure in the “main” part. That is, every period the computer independently drew at random one company values for each group of three persons. In the individual treatment, even though there was no group decision making in the main part, the same company value was given to each members of the groups.

Having 240 as the highest possible company value generates an adequate “profit distance” of 7.5 % between the RNNE bid of 60 and the naïve bid of 90. Consider that, after fixing the lower four company values, a highest possible company value of 183 generates equal profits for the 60 and the 90 bids.

Confidence levels are part of the cheap talk among group members. Incentivizing them would have likely biased the main bidding choice, which was the target of the experiment, and added complexity to the design.

In the chat window, participants received an id number 1–3 in the order they sent messages in that specific period. We asked participants to follow two basic rules: to be civil to one another and not use profanities, and not to identify themselves in any manner.

There were a proposal phase, a chat phase, and a group choice phase. Everyone simultaneously made an individual proposal about each of the fifteen lottery choices. Participants could then chat with their group. Any line with disagreement was highlighted. If the choices of all three group members were identical for a specific decision line, then we had a group choice. If case of disagreement, there were two other rounds of interaction. In case the group was still in disagreement in the line selected for payment, then earnings were zero for that part.

Note that when cumulative earnings were low, there was a problem of limited liability, which we will discuss in the Result section. The instruction explained: “What if my earnings are negative? They will be compensated with your other gains. More precisely, if you have a loss in a single period, it will decrease your cumulative earnings. If your cumulative earnings in this part are negative, they will decrease your earnings in other parts of the experiment. However, if at the end of the session your earnings are negative, you will receive $5”.

All reported p-values are based on two-sided tests unless otherwise stated.

In the easy task (difficult task), bidding 240 (120) yields a positive profit with probability 0.2 (0.4) and a loss y with probability 0.8 (0.6). If the cash balance is below y = 23.25 (y = 57.8) the eventual loss is inconsequential. When y < 23.25 (y < 57.8) the expected profit from a 240 (120) bid are higher than 5.4 (1.1) i.e. the expected profits from an optimal bid. Two caveats are in order. First, we guaranteed a $5 minimum earnings, which translates into 166.6 tokens, hence the relevant threshold for cash balances is 189.9 (224.4). Second, the reference cash balance includes the expected earnings from the individual lottery part and 2 lotteries, the part 3 and 4 endowments and the cumulative profits from the company takeover game up to that period.

Table 3 includes those observations. We dropped them instead from all following statistical and regression analyses.

In the difficult task, the optimal bid is 42. The range of near optimal bids covers 22 % of the action space to include also approximately optimal bids and to facilitate the statistical comparison with the easy task, where the optimal bid is linked to one of the five company value (20 % chance in case of random uniform choice). The expected profit from a bid of 31 is the same as from a bid of 53. In both easy and difficult tasks, near optimal bids are never loss-free.

In the control part, there are no significant differences in the fraction of optimal bids and fraction of winner’s curse bids across individual and group treatments for both the easy and difficult tasks (Robust Rank Order tests: n = 30, m = 60, p = 0.189 for optimal bids and p = 0.426 for winner’s curse bids in the easy task. In the difficult task, n = 15, m = 30, p = 0.246 for optimal bids and p = 0.369 for winner’s curse bids). Thus clearly the superiority of groups is not due to a better cohort of participants.

At the beginning of each period, subjects must make a proposal in the pre-discussion stage which worked as an open brick for their discussion and also saved their chat time which was up to 2 min. There were 15 periods involved. Thus the smart subject had 30 min in total to explain the strategy to the other two.

The difference is significant at 10 % (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, n = 20, p value = 0.09, one sample t test p value = 0.08).

The difference is significant at 1 % (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, n = 10, p value = 0.007, one sample t test p value = 0.002).

Some group bids were different from all the individual proposals of group members (3 % in the easy task and 28 % in the difficult task). The classification in the main text assigned those cases according to the closest distance in terms of expected profit between the group bids and each of the individual proposals. The regressions in Table 4, instead, coded as “median” only those proposals that were identical to the group bid.

The difference is significant at 10% according to the Wilcoxon signed-rank test, n = 30, p value = 0.07 and 5 % according to one sample t test p value = 0.02.

The difference is not statistically significant according to the Wilcoxon signed-rank test, n = 15, p value = 0.733 and one sample t test p value = 0.369.

Existing studies of group decision making greatly differ on this point, which crucially affects the incentives for communicating with others and for convincing others of one's opinion (Zhang and Casari, 2012). Cooper and Kagel (2005) randomly select one member’s proposal as the group choice. Blinder and Morgan (2005) and Gillet et al. (2009) either implement a majority rule or give members no time limit to reach a unanimous decision. Kocher and Sutter (2007) is the most closely related paper with a veto power feature. In a gift-exchange game, Kocher and Sutter allowed groups of three up to 10 rounds to reach agreement. If there was no agreement in the 10th round, each group member received only a show-up fee. Only one group failed to reach an agreement. They didn’t analyze the effect of such veto power though. Kagel et al. (2010) studied the veto power in a committee where only one of the three committee members is a veto player.

The observed levels of risk attitude cannot explain the winner’s curse phenomenon in the Individual treatment. Approximately 10 % of the participants showed risk seeking behaviour, and hence 90 % of bids should be either 38 or 60 in the easy task (see Table A3). Instead, they were 47.5 %. This finding by itself is an important result for the winner’s curse literature in general: the origin of the winner’s curse when participants decide in isolation does not lie in the risk attitude of participants.

See Zhang and Casari (2012) for a detailed literature review.

Table A3 in Appendix reports the detailed results. The fraction of risk neutral and risk seeking groups was lower than the fraction of risk neutral and risk seeking individuals (14.4 % vs. 13.64 %). The bulk of the choices reflected risk averse behavior. A two-sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov test did not show a significant difference though (p = 0.349).

Tindale et al. (2012) show that “social sharedness”—one of the basic group processes can lead to considerably different group outcomes, depending on whether shared knowledge interferes with the formal logic underlying the problem.

An exception is Sheremeta and Zhang (2010). Following a similar group risk preference elicitation methods, they find groups of two are more risk averse than individuals yet risk-aversion does not have a significant effect on groups’ bidding behavior in contests.

References

Bajari, P., & Hortacsu, A. (2003). The winner’s curse, reserve prices, and endogenous entry: Empirical insights from eBay auctions. The Rand Journal of Economics, 34(2), 329–355.

Ball, S. B., Bazerman, M. H., & Carroll, J. S. (1991). An evaluation of learning in the bilateral winner’s curse. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 48(1), 1–22.

Bereby-Meyer, Y., & Grosskopf, B. (2008). Overcoming the winner’s curse: An adaptive learning perspective. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 21(1), 15–27.

Blinder, A. S., & Morgan, J. (2005). Are two heads better than one? Monetary policy by committee. Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking, 37(5), 769–811.

Brodbeck, F. C., Kerschreiter, R., Mojzisch, A., Frey, D., & Schulz-Hardt, S. (2007). Group decision making under conditions of distributed knowledge: The information asymmetries model. Academy of Management Journal, 32, 459–479.

Carroll, J. S., Delquie, P., Halpern, J. & Bazerman, M. H. (1990). Improving negotiators’ cognitive processes. Working Paper, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA.

Charness, G., Cooper, D. J., & Grossman, Z. (2015). Silence is golden: Communication costs and team problem solving. Working Paper, University of California, Santa Barbara, CA.

Charness, G., Karni, E., & Levin, D. (2010). On the conjunction fallacy in probability judgment: New experimental evidence regarding Linda. Games and Economic Behavior, 68(2), 551–556.

Charness, G., & Levin, D. (2009). The origin of the winner’s curse: A laboratory study. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics, 1(1), 207–236.

Charness, G., & Sutter, M. (2012). Groups make better self-interested decisions. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 26(3), 157–176.

Cooper, D. J., & Kagel, J. H. (2005). Are two heads better than one? Team versus individual play in signaling games. American Economic Review, 95(33), 477–509.

Cooper, D. J., & Kagel, J. H. (2009). The role of context and team play in cross-game learning. Journal of the European Economic Association, 7(5), 1101–1139.

Cooper, D. J., Sutter, M. (2011). Role selection and team performance. IZA Discussion Paper No. 5892.

Cox, J. C., & Hayne, S. C. (2006). Barking up the right tree: Are small groups rational agents? Experimental Economics, 9(3), 209–222.

Davis, J. H. (1992). Some compelling intuitions about group consensus decisions, theoretical and empirical research, and interpersonal aggregation phenomena: Selected examples, 1950–1990. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 52(1), 3–38.

De Dreu, C. K. W., Nijstad, B. A., & Van Knippenberg, D. (2008). Motivated information processing in group judgment and decision making. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 12, 22–49.

Feri, F., Irlenbusch, B., & Sutter, M. (2010). Efficiency gains from team-based coordination—large-scale experimental evidence. American Economic Review, 100(4), 1892–1912.

Fischbacher, U. (2007). z-Tree-Zurich toolbox for readymade economic experiments. Experimental Economics, 10(2), 171–178.

Gillet, J., Schram, A., & Sonnemans, J. (2009). The tragedy of the commons revisited: The importance of group decision-making. Journal of Public Economics, 93(5–6), 285–297.

Grosskopf, B., Bereby-Meyer, Y., & Bazerman, M. (2007). On the robustness of the winner’s curse phenomenon. Theory and Decision, 63(4), 389–418.

Hinsz, V. B., Tindale, R. S., & Nagao, D. H. (2008). Accentuation of information processes and biases in group judgments integrating base-rate and case-specific information. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 44, 116–126.

Holt, C. A., & Laury, S. K. (2002). Risk aversion and incentive effects. American Economic Review, 92(5), 1644–1655.

Holt, C. A., & Sherman, R. (1994). The loser’s curse. American Economic Review, 84(3), 642–652.

Kagel, J. H., Sung, H., & Winter, E. (2010). Veto power in committees: An experimental study. Experimental Economics, 13(2), 167–188.

Kerr, N. L., MacCoun, R. J., & Kramer, G. P. (1996). When are N heads better (or worse) than one? Biased judgments in individuals and groups. In E. H. Witte & J. H. Davis (Eds.), Understanding group behavior: Consensual action by small groups (Vol. 1, pp. 105–136). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum Associates.

Kerr, N. L., & Tindale, R. S. (2004). Group performance and decision-making. Annual Review of Psychology, 55, 623–655.

Kocher, M. G., & Sutter, M. (2005). The decision maker matters: Individual versus group behavior in experimental beauty-contest games. Economic Journal, 115(500), 200–223.

Kocher, M. G., & Sutter, M. (2007). Individual versus group behavior and the role of the decision making procedure in gift-exchange experiments. Empirica, 31(1), 63–88.

Laughlin, P. R. (1980). Social combination processes of cooperative, problem-solving groups on verbal intellective tasks. In M. Fishbein (Ed.), Progress in social psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 127–155). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum Associates.

Laughlin, P. R. (1999). Collective induction: Twelve postulates. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 80(1), 50–69.

Laughlin, P. R., Bonner, B. L., & Miner, A. G. (2002). Groups perform better than the best individuals on letters-to-numbers problems. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 88(2), 605–620.

Laughlin, P. R., & Ellis, A. L. (1986). Demonstrability and social combination processes on mathematical intellective tasks. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 22(3), 177–189.

Laughlin, P. R., Hatch, E. C., Silver, J. S., & Boh, L. (2006). Groups perform better than the best individuals on letters-to-numbers problems: Effects of group size. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90(4), 644–651.

Laughlin, P. R., VanderStoep, S. W., & Hollingshead, A. B. (1991). Collective versus individual induction: recognition of truth, rejection of error, and collective information processing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(1), 50–67.

Laughlin, P. R., Zander, M. L., Knievel, E. M., & Tan, T. K. (2003). Groups perform better than the best individuals on letters-to-numbers problems: Informative equations and effective strategies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(4), 684–694.

Lorge, I., & Solomon, H. (1955). Two models of group behavior in the solution of eureka-type problems. Psychometrika, 20(2), 139–148.

Samuelson, W. (1984). Bargaining under asymmetric information. Econometrica, 52(4), 995–1006.

Samuelson, W. F., & Bazerman, M. H. (1985). The winner’s curse in bilateral negotiations. In V. L. Smith (Ed.), Research in experimental economics (Vol. 3). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Selten, R., Abbink, K., & Cox, R. (2005). Learning direction theory and the winner’s curse. Experimental Economics, 8(1), 5–20.

Sheremeta, R. M., & Zhang, J. (2010). Can groups solve the problem of over-bidding in contests? Social Choice and Welfare, 35(2), 175–197.

Smith, C. M., Tindale, R. S., & Steiner, L. (1998). Investment decisions by individuals and groups in “sunk cost” situations: The potential impact of shared representations. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 1, 175–189.

Sutter, M., Kocher, M., & Strauss, S. (2009). Individuals and teams in auctions. Oxford Economic Papers, 61(2), 380–394.

Tindale, R. S., Smith, C. M., Dykema-Engblade, A., & Kluwe, K. (2012). Good and bad group performance: Same process-different outcomes. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 15(5), 603–618.

Tor, A., & Bazerman, M. H. (2003). Focusing failures in competitive environments: Explaining decision errors in the Monty Hall game, the acquiring a company problem, and multiparty ultimatums. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 16(5), 353–374.

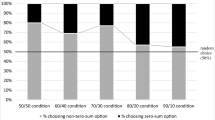

Zhang, J., & Casari, M. (2012). How groups reach agreement in risky choices: An experiment. Economic Inquiry, 50(2), 502–515.

Acknowledgments

Jingjing Zhang acknowledges financial support from the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF 135135) and the European Research Council (ERC Advanced Investigator Grant, ESEI-249433). We thank Anya Savikhin for valuable research assistance, Tim Cason for comments on an earlier version of the paper, two anonymous referees as well as seminar participants at the IMEBE meeting in Alicante, Spain, the ESA meetings in Tucson, and Bocconi University, Italy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Casari, M., Zhang, J. & Jackson, C. Same process, different outcomes: group performance in an acquiring a company experiment. Exp Econ 19, 764–791 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-015-9467-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-015-9467-7