Abstract

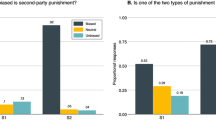

While the opportunity to punish selfish and reward generous behavior coexist in many instances in daily life, in most laboratory studies, the demand for punishment and reward are studied separately from one another. This paper presents the results from an experiment measuring the demand for reward and punishment by ‘unaffected’ third parties, separately and jointly. We find that the demand for costly punishment is substantially lower when individuals are also given the ability to reward. Similarly, the demand for costly reward is lower when individuals can also punish. The evidence indicates the reason for this is that costly punishment and reward are not only used to alter the material payoff of others as assumed by recent economic models, but also as a signal of disapproval and approval of others’ actions, respectively. When the opportunity exists, subjects often choose to withhold reward as a form of costless punishment, and to withhold punishment as a form of costless reward. We conclude that restricting the available options to punishing (rewarding) only, may lead to an increase in the demand for costly punishment (reward).

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

As Camerer and Fehr (2004, p. 55, emphasis added) write: “Social preferences refer to how people rank different allocations of material payoffs to themselves and others.” The willingness to punish or reward may be driven by a desire to reduce inequality in payoffs (e.g., Bolton and Ockenfels 2000; Fehr and Schmidt 1999) or a desire to hurt (help) people that have been unkind (kind) (e.g., Cox et al. 2007; Levine 1998; Rabin 1993).

In online marketplaces such as eBay, for example, traders can leave either positive or negative feedback; positive feedback is a form of reward as it allows sellers to charge higher prices, while negative feedback is a form of punishment for failing to provide the anticipated level of satisfaction as it lowers the prices sellers can charge (Houser and Wooders 2006). At work, individuals may reward good colleagues by being courteous and helpful to them, and punish bad ones by ignoring them or complaining to the employer.

Walker and Halloran (2004) study the demand for costly punishment and rewards in a one-shot public-good game. They find that both are equally effective in enforcing cooperation. However, their experimental design does not include a treatment with both reward and punishment opportunities. Sutter et al. (2010) find that subjects prefer using reward than punishment in a finitely-repeated public good game, even though punishment is more effective in encouraging cooperation.

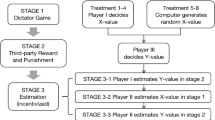

In Fehr and Fischbacher (2004) it was common knowledge that Player C was given 50 ECU. This amount reinforces the salience of the equal split between A and B (which the authors refer to as “the distribution norm”). We decided to endow Player C with an amount larger than 50 ECU, as an endowment of 50 implies that, unless Player A gives more than 50 ECU to Player B, A will earn more than Player C. Rewarding would therefore increase the earnings difference between A and C, while punishing would reduce it. We kept the endowment of 65 ECU to Player C private so as not to undermine the saliency of the equal split as a potential benchmark for judging which transfers are generous and which are selfish (McDonald et al. 2013).

The experimental instructions were adapted from Fehr and Fischbacher (2004) and use neutral language. Punishment points were referred to as subtraction points and reward points as addition points. The instructions are available at https://sites.google.com/site/nnikiforakis/.

Brandts and Charness (2011) present a survey of the existing evidence on the impact of the strategy method. They report that the treatment effects obtained when using the strategy method are consistent with those obtained when using the direct-response method.

In the second wave, participants not assigned the role of Player A received a set of instructions that explained the roles of Player B and C. These participants were asked to make the decision of Player C using the strategy method and were then randomly allocated the role of either Player B or Player C at the end of the experiment. We decided to have all participants not assigned the role of Player A make punishment/reward decisions so that we have a larger sample of participants who would answer the punishment/reward questions in the post-experiment questionnaire.

Some models, such as Cox et al. (2007) and Rabin (1993), allow for these preferences to depend on the intentions of the other player. An action is judged to be kind or unkind and, hence, worthy of reward or punishment, according to a reference material payoff. In Rabin (1993, p. 1286), for example, player j determines the kindness of player i by comparing his payoff (π j ) to the “equitable payoff”. The equitable payoff is defined as the average of the highest and lowest possible payoff that j could earn. Notice that Rabin’s definition considers reciprocity between two players: i and j. A plausible adaptation of this assumption for our game is that Player C judges A’s kindness by comparing the latter’s payoff (π A ) to the average of the highest and lowest possible payoff that Player B could earn. Reward and punishment do not affect the earnings of Player B, but could affect those of Player A. However, recall that C’s endowment is private information. Therefore, it seems unlikely that C’s judgment of A’s kindness would be affected by the presence of reward/punishment opportunities in our experiment. We provide evidence that this is indeed the case in Sect. 4.4.

Figures 1 and 2 do not include observations from four subjects (ID: 263, 445, 462, and 499). The subjects are included in the statistical analysis, but excluded here to offer a more accurate representation of behavior in the experiment. The responses of these subjects to a post-experiment questionnaire suggest that they were confused. The choices of these subjects can be seen in Figs. 6 and 7.

We follow previous studies in reporting results from linear regressions with individual random effects as this simplifies the interpretation of the coefficients. Tobit regressions yield qualitatively the same results both for punishment and reward. The results are also robust if we only use observations in which transfers were less or equal to 50 ECU for punishment, and greater or equal to 30 ECU for reward (see below).

The Wave coefficient is similar in both P and PR. This suggests that there was more punishment on average in the second wave of experiments than the first. While this may be a result worthy of further investigation, for our purposes, what is most important is that when an interaction variable PR*WAVE is included in the regressions, we find that it is insignificant (p-value = 0.90). Thus, our treatment effects are unaffected by this parameter. We also tried including additional socio-demographic characteristics in regression (3) to check the robustness of our results. When Age, Economics [major] and Gender variables are included in the estimation, our results are unaffected.

One may wonder whether the reduced demand for costly punishment could be due to subjects switching from punishing to rewarding. This is not the case however, as can be easily seen by examining the demand for punishing transfers of zero in Fig. 1. Such transfers are almost never rewarded. Also, if this explanation was behind the reduction in the demand for costly punishment, we would expect that the demand for points (either reward or punishment points) should be at least as high in treatment PR as in P. However, controlling for the level of transfer this is almost never the case.

The Wave variable is insignificant as can be seen in columns (1) and (2) in Table 3. This indicates that the demand for reward was the same in both waves of the experiment. When an interaction variable PR*WAVE is included in the regressions it is insignificant for all treatments (p-value > 0.5). We also tested the robustness of our result by controlling for different socio-demographic characteristics. Controlling for Age, Economics [major] and Gender does not affect our results.

We would like to thank an anonymous referee and the co-editor (Jacob Goeree) for suggesting this analysis.

Recall from Table 4 that transfers lower than 50 ECU attracted a significant number of punishment points. Thus, transfers of 50 ECU can be used as a baseline to evaluate Player C’s reaction to the choice of Player A.

The difference remains insignificant if we consider transfers greater or equal to 30 ECU (p-value = 0.976).

References

Almenberg, J., Dreber, A., Apicella, C. L., & Rand, D. G. (2011). Third party reward and punishment: group size, efficiency and public goods. In Psychology and punishment. New York: Nova Publishing.

Andreoni, J., Harbaugh, W., & Vesterlund, L. (2003). The carrot or the stick: rewards, punishment and cooperation. The American Economic Review, 93(3), 893–902.

Balafoutas, L., & Nikiforakis, N. (2012). Norm enforcement in the city: a natural field experiment. European Economic Review, 56(8), 1773–1785.

Berg, J., Dickhaut, J., & McCabe, K. (1995). Trust, reciprocity, and social history. Games and Economic Behavior, 10, 122–142.

Bolton, G. E., & Ockenfels, A. (2000). ERC: a theory of equity, reciprocity, and competition. American Economic Review, 166–193.

Brandts, J., & Charness, G. (2011). The strategy versus the direct-response method: a first survey of experimental comparisons. Experimental Economics, 14(3), 375–398.

Camerer, C. F., & Fehr, E. (2004). Measuring social norms and preferences using experimental games: a guide for social scientists. In J. Henrich, R. Boyd, S. Bowles, C. Camerer, E. Fehr, & H. Gintis (Eds.), Foundations of human sociality: economic experiments and ethnographic evidence from fifteen smallscale societies (pp. 55–95). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Charness, G., Cobo-Reyes, R., & Jimenez, N. (2008). An investment game with third-party intervention. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 68, 18–28.

Chaudhuri, A. (2011). Sustaining cooperation in laboratory public goods experiments: a selective survey of the literature. Experimental Economics, 14(1), 47–83.

Cox, J. C., Friedman, D., & Gjerstadt, S. (2007). A tractable model of reciprocity and fairness. Games and Economic Behavior, 59, 17–45.

Dellarocas, C., & Woods, C. A. (2008). The sound of silence in online feedback: estimating trading risks in the presence of reporting bias. Management Science, 54, 460–476.

Denant-Boemont, L., Masclet, D., & Noussair, C. (2007). Punishment, counterpunishment and sanction enforcement in a social dilemma experiment. Economic Theory, 33(1), 145–167.

Ellingsen, T., & Johannesson, M. (2008). Anticipated verbal feedback induces altruistic behavior. Evolution and Human Behavior, 29, 100–105.

Engelmann, D., & Nikiforakis, N. (2012). In the long run we are all dead: on the benefits of peer punishment in rich environments (Working Paper ECON 12-22). University of Mannheim, Department of Economics.

Fehr, E., & Fischbacher, U. (2004). Third-party punishment and social norms. Evolution and Human Behavior, 25, 63–87.

Fehr, E., & Gächter, S. (2000). Cooperation and punishment in public goods experiments. American Economic Review, 90(4), 980–994.

Fehr, E., & Schmidt, K. M. (1999). A theory of fairness, competition, and cooperation. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114(3), 817–868.

Fehr, E., Kirchsteiger, G., & Riedl, A. (1993). Does fairness prevent market clearing? An experimental investigation. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 108(2), 437–459.

Fehr, E., Hoff, K., & Kshetramade, M. (2008). Spite and development. American Economic Review: Papers & Proceedings, 98(2), 494–499.

Fischbacher, U. (2007). Z-tree: Zurich toolbox for readymade economic experiments. Experimental Economics, 10, 171–178.

Gächter, S., & Herrmann, B. (2009). Reciprocity, culture, and human cooperation: previous insights and a new cross-cultural experiment. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences, 364, 791–806.

Gächter, S., Renner, E., & Sefton, M. (2008). The long run benefits of punishment. Science, 322, 1510.

Greiner, B. (2004). An online recruitment system for economic experiments (MPRA paper).

Guala, F. (2012). Reciprocity weak or strong? What punishment experiments do (and do not) demonstrate. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 35, 1–15.

Güth, W., Schmittberger, R., & Schwarze, B. (1982). An experimental analysis of ultimatum bargaining. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 3, 367–388.

Henrich, J., McElreath, R., Barr, A., Ensminger, J., Barrett, C., Bolyanatz, A., et al. (2006). Costly punishment across human societies. Science, 312, 1767.

Houser, D., & Wooders, J. (2006). Reputation in auctions: theory and evidence from eBay. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 15(2), 353–370.

Levine, D. (1998). Modeling altruism and spitefulness in experiments. Review of Economic Dynamics, 1, 593–622.

Marlowe, F. W., Berbesque, C., Barr, A., Barrett, C., et al. (2008). More ‘altruistic’ punishment in larger societies. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences, 275(1634), 587–592.

Masclet, D., Noussair, C., Tucker, S., & Villeval, M. C. (2003). Monetary and nonmonetary punishment in the voluntary contributions mechanism. The American Economic Review, 93(1), 366–380.

McDonald, I., Nikiforakis, N., Olekalns, N., & Sibly, H. (2013). Social comparisons and reference group formation: some experimental evidence. Games and Economic Behavior, 79, 75–89.

Nikiforakis, N. (2008). Punishment and counter-punishment in public good games: can we really govern ourselves? Journal of Public Economics, 92(1–2), 91–112.

Noussair, C., & Tucker, S. (2005). Combining monetary and social sanctions to promote cooperation. Economic Inquiry, 43(3), 649–660.

Rabin, M. (1993). Incorporating fairness into game theory and economics. The American Economic Review, 83(5), 1281–1302.

Rand, D., Dreber, A., Ellingson, T., Fudenberg, D., & Nowak, M. (2009). Positive interactions promote public cooperation. Science, 325(5945), 1272–1275.

Reuben, E., & van Winden, F. (2008). Social ties and coordination on negative reciprocity: the role of affect. Journal of Public Economics, 92(1–2), 34–53.

Rockenbach, B., & Milinski, M. (2006). The efficient interaction of indirect reciprocity and costly punishment. Nature, 444, 718–723.

Sefton, M., Shupp, R., & Walker, J. (2007). The effect of rewards and sanctions in provision of public goods. Economic Inquiry, 45(4), 671–690.

Sutter, M., Haigner, S., & Kocher, M. (2010). Choosing the stick or the carrot? Endogenous institutional choice in social dilemma situations. Review of Economic Studies, 77, 1540–1566.

Ule, A., Schram, A., Riedl, A., & Cason, T. (2009). Indirect punishment and generosity toward strangers. Science, 326(5960), 1701–1704.

Walker, J. H., & Halloran, M. A. (2004). Rewards and sanctions and the provision of public goods in one-shot settings. Experimental Economics, 7(3), 235–247.

Xiao, E., & Houser, D. (2005). Emotion expression in human punishment behavior. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 102(20), 7398–7401.

Xiao, E., & Houser, D. (2009). Avoiding the sharp tongue: anticipated written messages promote fair economic exchange. Journal of Economic Psychology, 30, 393–404.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

We would like to thank the Co-Editor (Jacob Goeree), two anonymous referees, Aurelie Dariel, Peter Duersch, Simon Loertscher, Tom Wilkening, participants at the Asia-Pacific meetings of the Economic Science Association in Melbourne (2010), the 5th Australian-New Zealand Workshop in Experimental Economics, and seminar participants at Monash University, the University of Innsbruck, and the University of Melbourne for helpful comments and discussions. The results from the ‘first wave’ of the experiments formed the basis for Helen’s Honors thesis at the University of Melbourne. The authors acknowledge funding from the Department of Economics, and the Faculty of Business and Economics at the University of Melbourne.

Appendix

Appendix

The demand for costly punishment by individual. The first digit in each subfigure indicates the treatment in which the individual participated (1 = Treatment P; 2 = Treatment PR; 3 = Treatment R). The number after the comma is a unique subject ID. The dashed lines help separate visually subjects belonging to a different treatment

The demand for costly reward by individual. The first digit in each subfigure indicates the treatment in which the individual participated (1 = Treatment P; 2 = Treatment PR; 3 = Treatment R). The number after the comma is a unique subject ID. The dashed lines help separate visually subjects belonging to a different treatment

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nikiforakis, N., Mitchell, H. Mixing the carrots with the sticks: third party punishment and reward. Exp Econ 17, 1–23 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-013-9354-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-013-9354-z