Abstract

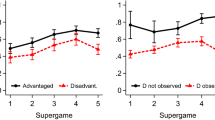

In this paper, we analyse if individual inequality aversion measured with simple experimental games depends on whether the monetary endowment in these games is either a windfall gain (“house money”) or a reward for a certain effort-related performance. We then examine whether the way of preference elicitation affects the explanatory power of inequality aversion in social dilemma situations. Our results indicate that individual inequality aversion measured by the model of Fehr and Schmidt (Quarterly Journal of Economics 114(3):817–868, 1999) is not generally robust to the way endowments emerge. The inequality aversion model has only low predictive power for individual behaviour. It performs best when the endowment is house money and relatively small.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The house money effect has also been investigated in other areas of research and with different experimental settings: for house money effects in public good games see e.g. Clark (2002), Harrison (2007), Cherry et al. (2005), Kroll et al. (2007), for house money effects in risky choices see e.g. Keeler et al. (1985), Thaler and Johnson (1990), Arkes et al. (1994), Keasey and Moon (1996), and Ackert et al. (2006).

In the following, all conditions are stated for the case of two players. The generalisation to the n-player case is straightforward and can be found in Fehr and Schmidt (1999).

This condition is employed by Fehr and Schmidt (1999) in order to facilitate the critical condition for cooperation in a voluntary contribution game (VCG). Proposition 4 of their proof (part C, p. 862) states that a player with β i >1−m, where m denotes the marginal per capita return of the public investment, chooses to cooperate in a VCG if the following condition is met: k/(n−1)≤(m+β i −1)/(α i +β i ) where k are players with β i <1−m. If α i ≥β i this is the sole condition that has to be fulfilled. If we abandon α i ≥β i a second condition might become binding, namely k/(n−1)≤m/2. As we will see in Sect. 3, for treatments with cooperation hypothesis this condition always holds in our experiment.

Namely, title and authors of the article, name, volume, and page number of the journal.

They were informed about their relative performance, so subjects could infer to which group (rich or poor) they belong.

Payoffs in games A and B were determined in experimental pre-tests to ensure that we obtained a sufficient number of observations for each decision.

With respect to this aspect our design differs from previous experiments (see the introduction for an overview). However, since in real world decision situations inequity concerns often prevail in situations were both sides have to show effort in order to create the cake at stake we believe that our implementation is warrantable.

The €1.00 was chosen as a minimum payoff in order to avoid the possibility of zero payoffs.

While the direct-response method is often considered as the first-best solution, Brandts and Charness (2011) argue: “[The strategy method]… may lead subjects to make more thoughtful decisions and, through the analysis of a complete strategy, may lead to better insights into the motives and thought-processes underlying subjects’ decisions” (p. 377).

As the threshold values for F&S parameters, α i =0.1 and β i =0.4, also the value for the punishment costs, c=0.1, was derived from the F&S model. More precisely, the value c=0.1 was chosen in order to make for game D (the PD with punishment) punishment of a defector a credible threat for a subject with α i >0.1 (see Sect. 3.4).

If not otherwise stated all statistical tests are two-sided throughout the paper.

The chi-square test statistics are: No effort rich vs. Effort rich (chi-squared=12.7, df=3, p=0.005), No effort rich vs. Effort poor (chi-squared=14.2, df=3, p=0.003) and No effort rich vs. No effort poor (chi-squared=12.7, df=3, p=0.005).

Nearly identical results are obtained when the logit regression for the PD is done with subsamples which are pooled across treatment variables (Effort, No Effort, Rich and Poor). In particular C-hypothesis is significant in No effort poor only.

This conclusion is also supported when the logit regression for the PD is done with subsamples which are pooled across treatment variables (Effort, No Effort, Rich and Poor).

Nearly identical results are obtained when the logit regression for the punishment decision is done with subsamples which are pooled across treatment variables (Effort, No Effort, Rich and Poor). In particular, P-hypothesis is significant in No Effort rich only.

References

Ackert, L. F., Charupat, N., Church, B. K., & Deaves, R. (2006). An experimental examination of the house money effect in a multi-period setting. Experimental Economics, 9(1), 5–16.

Arkes, H. R., Joyner, C. A., Pezzo, M. V., Gradwohl Nash, J., Siegel-Jacoby, K., & Stone, E. (1994). The psychology of windfall gains. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 59(3), 331–347.

Babcock, L., & Loewenstein, G. (1997). Explaining bargaining impasse: the role of self-serving biases. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 11(1), 109–126.

Ben-Ner, A., Putterman, L., Kong, F., & Magan, D. (2004). Reciprocity in a two-part dictator game. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 53(3), 333–352.

Blanco, M., Engelmann, D., & Normann, H.-T. (2011). A within-subject analysis of other-regarding preferences. Games and Economic Behavior, 72(2), 321–338.

Brandts, J., & Charness, G. (2011). The strategy versus the direct-response method: a first survey of experimental comparisons. Experimental Economics, 14(3), 375–398.

Bolton, G. E., & Ockenfels, A. (2000). ERC. A theory of equity, reciprocity and competition. American Economic Review, 90(1), 166–193.

Brosig, J., Riechmann, T., & Weimann, J. (2007). Selfish in the end? An investigation of consistency and stability of individual behaviour. FEMM Working Paper No. 07005, University of Magdeburg.

Charness, G., & Grosskopf, B. (2001). Relative payoffs and happiness: an experimental study. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 45, 301–328.

Charness, G., & Rabin, M. (2002). Understanding social preferences with simple tests. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117, 817–868.

Cherry, T. L. (2001). Mental accounting and other-regarding behaviour: evidence from the lab. Journal of Economic Psychology, 22(5), 605–615.

Cherry, T. L., Frykblom, P., & Shogren, J. F. (2002). Hardnose the dictator. American Economic Review, 92(4), 1218–1221.

Cherry, T. L., Kroll, S., & Shogren, J. F. (2005). The impact of endowment heterogeneity and origin on public good contributions: evidence from the lab. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 57(3), 357–365.

Clark, J. (2002). House money effects in public good experiments. Experimental Economics, 5, 223–231.

Dannenberg, A., Riechmann, T., Sturm, B., & Vogt, C. (2010), Stability and explanatory power of inequality aversion—an investigation of the house money effect. ZEW Discussion Paper No. 10-006, Mannheim.

Dufwenberg, M., & Kirchsteiger, G. (2004). A theory of sequential reciprocity. Games and Economic Behavior, 47, 268–298.

Eckel, C. C., & Grossman, P. J. (1996). Altruism in anonymous dictator games. Games and Economic Behavior, 16, 181–191.

Engelmann, D., & Strobel, M. (2004). Inequality aversion, efficiency, and maximin preferences in simple distribution experiments. American Economic Review, 94(4), 857–869.

Falk, A., & Fischbacher, U. (2006). A theory of reciprocity. Games and Economic Behavior, 54(2), 293–315.

Falk, A., Fehr, E., & Fischbacher, U. (2008). Testing theories of fairness—intentions matter. Games and Economic Behavior, 62, 287–303.

Fehr, E., & Gächter, S. (2000). Cooperation and punishment in public goods experiments. American Economic Review, 90(4), 980–994.

Fehr, E., & Schmidt, K. M. (1999). A theory of fairness, competition, and cooperation. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114(3), 817–868.

Fehr, E., & Schmidt, K. M. (2006). The economics of fairness, reciprocity and altruism—experimental evidence and new theories. In S.-C. Kolm & J. M. Ythier (Eds.), Handbook on the economics of giving, reciprocity and altruism (Vol. 1, pp. 615–691). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Fischbacher, U. (2007). z-Tree: Zurich toolbox for ready-made economic experiments. Experimental Economics, 10(2), 171–178.

Fischbacher, U., & Gächter, S. (2010). Social preferences, beliefs, and the dynamics of free riding in public goods experiments. The American Economic Review, American Economic Association, 100(1), 541–556.

Goeree, J. K., & Holt, C. A. (2000). Asymmetric inequality aversion and noisy behavior in alternating-offer bargaining games. European Economic Review, 44(4–6), 1079–1089.

Greiner, B. (2003). An online recruitment system for economic experiments. In K. Kremer & V. Macho (Eds.), Forschung und wissenschaftliches Rechnen 2003. GWDG Bericht 63 (pp. 79–93). Göttingen: Ges. für Wiss. Datenverarbeitung, 2004.

Harrison, G. (2007). House money effects in public good experiments: comment. Experimental Economics, 10(4), 429–437.

Hoffman, E., McCabe, K., Shachat, K., & Smith, V. (1994). Preferences, property rights and anonymity in bargaining games. Games and Economic Behavior, 7(3), 346–380.

Iriberri, N., & Rey-Biel, P. (2011). The role of role uncertainty in modified dictator games. Experimental Economics, 14(2), 160–180.

Keasey, K., & Moon, P. (1996). Gambling with the house money in capital expenditure decisions: an experimental analysis. Economics Letters, 50(1), 105–110.

Keeler, J., James, W., & Abdel-Ghany, M. (1985). The relative size of windfall income and the permanent income hypothesis. Journal of Business and Statistics, 3(3), 209–215.

Kosfeld, M., Okada, A., & Riedl, A. (2009) Institution formation in public goods games. American Economic Review, 99(4), 1335–1355.

Kroll, S., Cherry, T. L., & Shogren, J. F. (2007). The impact of endowment heterogeneity and origin in best-shot public good games. Experimental Economics, 10(4), 411–428.

Ockenfels, A., & Weimann, J. (1999). Types and patterns: an experimental East-West-German comparison of cooperation and solidarity. Journal of Public Economics, 71(2), 275–287.

Oxoby, R. J. & Spraggon, J. (2008). Mine and yours: property rights in dictator games. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 65(3–4), 703–713.

Reinstein, D., & Riener, G. (2009). House money effects on charitable giving: an experiment. Discussion paper.

Rosenboim, M., & Shavit, T. (2011). Whose money is it anyway? Using prepaid incentives in experimental economics to create a natural environment. Experimental Economics, doi:10.1007/s10683-011-9294-4.

Ruffle, B. J. (1998). More is better, but fair is fair: tipping in dictator and ultimatum games. Games and Economic Behavior, 23(2), 247–265.

Teyssier, S. (2009). Inequity and risk aversion in sequential public good games. Working Paper 09-19, GATE, Écully.

Thaler, R. H., & Johnson, E. J. (1990). Gambling with the house money and trying to break even: the effects of prior outcomes on risky choices. Management Science, 36(6), 643–660.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank two anonymous referees and the editor for very useful comments and suggestions. Financial support from the German Science Foundation is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

In this appendix we derive the Nash equilibrium for game C (PD) and the subgame perfect equilibrium (SPE) for game D (PD-P).

PD game (C—cooperation, D—defection) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

PD | j | ||

Utility | C | D | |

i | C | 8.4, 8.4 | 4.2−7.0α i , 11.2−7.0β j |

D | 11.2−7.0β i , 4.2−7.0α j | 7.0, 7.0 | |

Strategy combination {i,j} | i | j |

|---|---|---|

{C,C}a | 8.4>11.2−7.0β i ⇒β i >0.4 | 8.4 > 11.2 - 7.0β j ⇒β j >0.4 |

{D,D}a | 7.0>4.2−7.0α i ⇒α i >−0.4 | 7.0>4.2−7.0α j ⇒α j >−0.4 |

{C,D} | 4.2−7.0α i >7.0⇒α i <−0.4 | 11.2−7.0β j >8.4⇒β j <0.4 |

{D,C} | 11.2−7.0β i >8.4⇒β i <0.4 | 4.2−7.0α j >7.0⇒α j <−0.4 |

PD-P game (P—punishment, NP—no punishment) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

PD-P: {C,C} | j | ||

Utility | P | NP | |

i | P | 4.0, 4.0 | 8.0−3.6β i , 4.4−3.6α j |

NP | 4.4−3.6α i , 8.0−3.6β j | 8.4, 8.4 | |

Strategy combination {i,j} | i | j |

|---|---|---|

{NP,NP}a | 8.4>8.0−3.6β i ⇒β i >−0.1 | 8.4>8.0−3.6β j ⇒β j >−0.1 |

{P,P}a | 4.0>4.4−3.6α i ⇒α i >0.1 | 4.0>4.4−3.6α j ⇒α j >0.1 |

{NP,P} | 4.4−3.6α i >4.0⇒α i <0.1 | 8.0−3.6β j >8.4⇒β j <−0.1 |

{P,NP} | 8.0−3.6β i >8.4⇒β i <−0.1 | 4.4−3.6α j >4.0⇒α j <0.1 |

PD-P: {C,D} | j | ||

|---|---|---|---|

Utility | P | NP | |

i | P | −0.2−7.0α i , 6.8−7.0β j | 3.8−3.4α i , 7.2−3.4β j |

NP | 0.2−10.6α i , 10.8−10.6β j | 4.2−7.0α i , 11.2−7.0β j | |

Strategy combination {i,j} | i | j |

|---|---|---|

{NP,NP}a | 4.2−7.0α i >3.8−3.4α i ⇒α i <0.1 | 11.2−7.0β j >10.8−10.6β j ⇒β j >−0.1 |

{P,P} | −0.2−7.0α i >0.2−10.6α i ⇒α i >0.1 | 6.8−7.0β j >7.2−3.4β j ⇒β j <−0.1 |

{NP,P} | 0.2−10.6α i >−0.2−7.0α i ⇒α i <0.1 | 10.8−10.6β j >11.2−7.0β j ⇒β j <−0.1 |

{P,NP}a | 3.8−3.4α i >4.2−7.0α i ⇒α i >0.1 | 7.2−3.4β j >6.8−7.0β j ⇒β j >−0.1 |

PD-P: {D,C} | j | ||

|---|---|---|---|

Utility | P | NP | |

i | P | 6.8−7.0β i , −0.2−7.0α j | 10.8−10.6β i , 0.2−10.6α j |

NP | 7.2−3.4β i , 3.8−3.4α j | 11.2−7.0β i , 4.2−7.0α j | |

Strategy combination {i,j} | i | j |

|---|---|---|

{NP,NP}a | 11.2−7.0β i >10.8−10.6β i ⇒β i >−0.1 | 4.2−7.0α j >3.8−3.4α j ⇒α j <0.1 |

{P,P} | 6.8−7.0β i >7.2−3.4β i ⇒β i <−0.1 | −0.2−7.0α j >0.2−10.6α j ⇒α j >0.1 |

{NP,P}a | 7.2−3.4β i >6.8−7.0β i ⇒β i >−0.1 | 3.8−3.4α j >4.2−7.0α j ⇒α j >0.1 |

{P,NP} | 10.8−10.6β i >11.2−7.0β i ⇒β i <−0.1 | 0.2−10.6α j >−0.2−7.0α j ⇒α j <0.1 |

PD-P: {D,D} | j | ||

|---|---|---|---|

Utility | P | NP | |

i | P | 2.6, 2.6 | 6.6−3.6β i , 3.0−3.6α j |

NP | 3.0−3.6α i , 6.6−3.6β j | 7.0, 7.0 | |

Strategy combination {i,j} | i | j |

|---|---|---|

{NP,NP}a | 7.0>6.6−3.6β i ⇒β i >−0.1 | 7.0>6.6−3.6β j ⇒β j >−0.1 |

{P,P}a | 2.6>3.0−3.6α i ⇒α i >0.1 | 2.6>3.0−3.6α j ⇒α j >0.1 |

{NP,P} | 3.0−3.6α i >2.6⇒α i <0.1 | 6.6−3.6β j >7.0⇒β j <−0.1 |

{P,NP} | 6.6−3.6β i >7.0⇒β i <−0.1 | 3.0−3.6α j >2.6⇒α j <0.1 |

We analyse 10 possible i−j-matchings FAIR-FAIR, FAIR-CARING, CARING-CARING, FAIR-ENVIOUS, FAIR-EGO, ENVIOUS-ENVIOUS, CARING-ENVIOUS, CARING-EGO, ENVIOUS-EGO, EGO-EGO. Thereby, we substitute the Nash equilibrium of the punishment subgame into the payoff matrix of the contribution stage in the PD. Here we show only the matchings ENVIOUS-ENVIOUS and ENVIOUS-EGO. All other matchings can be analysed accordingly.

ENVIOUS-ENVIOUS | |||

PD | j | ||

Utility | C | D | |

i | C | 8.4, 8.4 | 3.8−3.4α i , 7.2−3.4β j |

D | 7.2−3.4β i , 3.8−3.4α j | 7.0, 7.0 | |

ENVIOUS-EGO | |||

PD | j | ||

Utility | C | D | |

i | C | 8.4, 8.4 | 3.8−3.4α i , 7.2−3.4β j |

D | 11.2−7.0β i , 4.2−7.0α j | 7.0, 7.0 | |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dannenberg, A., Riechmann, T., Sturm, B. et al. Inequality aversion and the house money effect. Exp Econ 15, 460–484 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-011-9308-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-011-9308-2