Abstract

This study examines the association between sibship size and wealth in adulthood. The study draws on resource dilution theory and additionally discusses potentially wealth-enhancing consequences of having siblings. Data from the German Socio-Economic Panel Study (SOEP, N = 3502 individuals) are used to estimate multilevel regression models adjusted for concurrent parental wealth and other important confounders neglected in extant work. The main results of the current study show that additional siblings reduce wealth by about 38%. Parental wealth moderates the association so that sibship size is more negatively associated with filial wealth when parents are wealthier. Birth order position does not moderate the association between sibship size and wealth. The findings suggest that fertility in the family of origin has a systematic impact on wealth attainment and may contribute to population-level wealth inequalities independently from other socio-economic characteristics in families of origin such as parental wealth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The confluence model states that the average intellectual environment in a family is important for child development. Young children reduce the “intellectual average”, and therefore, larger sibship sizes have negative developmental consequences (especially for first-born children). At the same time, interaction between siblings and tutoring of younger siblings by older siblings may improve outcomes for older siblings (Härkönen 2014; Zajonc and Markus 1975).

Full, half, step and adopted siblings are all included, as resource dilution may occur through all these different types of siblings. A control variable for half and step siblings is included in multivariate models.

Respondents from booster samples added in 2012 and thereafter are dropped as they have not participated in the wealth module in 2012 or they provide too few cases where parents and children are observed in separate households.

The birth order index is constructed as follows: Birth order index = (Birth order position of individual/((Number of siblings + 1)/2)) − 1. For instance, an only child has the value 0.000 (= [1/1] − 1), the first-born child in a two-child family has the value − 0.333 (= [1/1.5] − 1), and the second-born child in a two-child family has the value 0.333 (= [2/1.5] − 1).

The question regarding risk preferences is: “Are you generally a person who is fully prepared to take risks or do you try to avoid taking risks?" with answer categories (11-point scale) from “risk averse” to “fully prepared to take risks”. This question has been fielded in 2004, 2006 and then annually since 2008 until 2016. The question regarding impulsiveness is: “Do you generally think things over for a long time before acting—in other words, are you not impulsive at all? Or do you generally act without thinking things over for long, in other words, are you very impulsive?” with answer categories (11-point scale) from “not at all impulsive” to “very impulsive”. The question has been fielded in 2008 and 2013.

It is assumed that these characteristics do not change after a childbirth.

Family fixed-effects models cannot be estimated as the sibship size is a family-level characteristic.

References

Anastasi, A. (1956). Intelligence and family size. Psychological Bulletin,53(3), 187–209.

Angrist, J. D., Lavy, V., & Schlosser, A. (2010). Multiple experiments for the causal link between the quantity and quality of children. Journal of Labor Economics,28(4), 773–824.

Bach, S., Thiemann, A. (2016). Inheritance tax revenue low despite surge in inheritances. DIW Economic Bulletin 4/5 2016. Berlin: Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung. https://www.diw.de/documents/publikationen/73/diw_01.c.525511.de/diw_econ_bull_2016-04-1.pdf. Accessed July 20, 2016.

Baranowska-Rataj, A., de Luna, X., & Ivarsson, A. (2016). Does the number of siblings affect health in midlife? Evidence from the Swedish prescribed drug register. Demographic Research,35(43), 1259–1302.

Becker, G. S., & Tomes, N. (1976). Child endowments and the quantity and quality of children. Journal of Political Economy,84, S143–S162.

Behrman, J. R., Pollak, R. A., & Taubman, P. (1982). Parental preferences and provision for progeny. Journal of Political Economy,90, 52–73.

Bernardi, F., & Boertien, D. (2017). Explaining conflicting results in research on the heterogeneous effects of parental separation on children’s educational attainment according to social background. European Journal of Population,33, 243–266.

Bernardi, F., & Radl, J. (2014). The long-term consequences of parental divorce for children’s educational attainment. Demographic Research,30, 1653–1680.

Bischof, D. (2017). New graphic schemes for Stata: Plotplain and plotting. Stata Journal,17, 748–759.

Black, S. E., Devereux, P. J., & Salvanes, K. G. (2005). The more the merrier? The effect of family size and birth order on children’s education. The Quarterly Journal of Economics,120(2), 669–700.

Black, S. E., Devereux, P. J., & Salvanes, K. G. (2010). Small family, smart family? Family size and the IQ scores of young men. Journal of Human Resources,45(1), 33–58.

Blake, J. (1989). Family size and achievement. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Bobbitt-Zeher, D., Downey, D. B., & Merry, J. (2016). Number of siblings during childhood and the likelihood of divorce in adulthood. Journal of Family Issues,37, 2075–2094.

Booth, A. L., & Kee, H. J. (2008). Birth order matters: The effect of family size and birth order on educational attainment. Journal of Population Economics,22(2), 367–397.

Brown, S., Garino, G., & Taylor, K. (2013). Household debt and attitudes towards risk. Review of Income and Wealth,59(2), 283–304.

Cameron, L., Erkal, N., Gangadharan, L., & Meng, X. (2013). Little emperors: Behavioral impacts of China’s one-child policy. Science,339(6122), 953–957.

Cavapozzi, D., Fiume, A., G, C., & Weber, G. (2011). Human capital accumulation and investment behaviour. In A. Börsch-Supan, M. Brandt, K. Hank, & M. Schröder (Eds.), The individual and the welfare state: Life histories in Europe: 45–66. Berlin: Springer.

Charles, K. K., & Hurst, E. (2003). The correlation of wealth across generations. Journal of Political Economy,111(6), 1155–1182.

Conley, D., & Glauber, R. (2006). Parental educational investment and children’s academic risk: Estimates of the impact of sibship size and birth order from exogenous variation in fertility. Journal of Human Resources,51(4), 722–737.

Donkers, B., & van Soest, A. (1999). Subjective measures of household preferences and financial decisions. Journal of Economic Psychology,20(6), 613–642.

Downey, D. B. (1995). When bigger is not better: Family size, parental resources, and children’s educational performance. American Sociological Review,60(5), 746–761.

Downey, D. B. (2001). Number of siblings and intellectual development: The resource dilution explanation. American Psychologist,56(6–7), 497–504.

Downey, D. B., & Condron, D. J. (2004). Playing well with others in kindergarten: The benefit of siblings at home. Journal of Marriage and Family,66(2), 333–350.

Emery, T. (2013). Intergenerational transfers and European families: Does the number of siblings matter? Demographic Research,29(10), 247–274.

Friedline, T., Masa, R. D., & Chowa, G. A. (2015). Transforming wealth. Using the inverse hyperbolic sine (IHS) and splines to predict youth’s math achievement. Social Science Research,49, 264–287.

Galton, F. (1874). English men of science: Their nature and nurture. London: Macmillan.

Gibbs, B. G., Workman, J., & Downey, D. B. (2016). The (conditional) resource dilution model: State- and community-level modifications. Demography,53(3), 723–748.

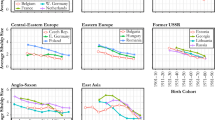

Goldstein, J. R., & Kreyenfeld, M. (2011). Has east germany overtaken west Germany? Recent trends in order-specific fertility. Population and Development Review,37(3), 453–472.

Grätz, M., & Torche, F. (2016). Compensation or reinforcement? The stratification of parental responses to children’s early ability. Demography,53, 1883–1904.

Guo, G., & Vanwey, L. K. (1999). Sibship size and intellectual development: Is the relationship causal? American Sociological Review,64(2), 169–187.

Hansen, M. N. (2014). Self-made wealth or family wealth? Changes in intergenerational wealth mobility. Social Forces,93(2), 457–481.

Hanushek, E. A. (1992). The trade-off between child quantity and quality. Journal of Political Economy,100(1), 84–117.

Härkönen, J. (2014). Birth order effects on educational attainment and educational transitions in west Germany. European Sociological Review,30(2), 166–179.

Household Finance and Consumption Network (HFCN). (2016). The household finance and consumption survey. Results from the second wave. Statistics paper series 18. Frankfurt: European Central Bank.

Iacovou, M. (2008). Family size, birth order, and educational attainment. Marriage & Family Review,42, 35–57.

Institute for Social Research. (2015). Accuracy code for imputation of 2007 wealth summary variables. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan. Retrieved May 19, 2015 from http://simba.isr.umich.edu/cb.aspx?vList=S817A.

Jacob, M. (2011). Do brothers affect their sisters’ chances to graduate? An analysis of sibling sex composition effects on graduation from a university or a Fachhochschule in Germany. Higher Education,61(3), 277–291.

Jokela, M. (2014). Life-course fertility patterns associated with childhood externalizing and internalizing behaviors. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry,23(12), 1201–1210.

Kalmijn, M. (2013). How mothers allocate support among adult children: Evidence from a multiactor survey. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences,68(2), 268–277.

Keister, L. A. (2003). Sharing the wealth: The effect of siblings on adults’ wealth ownership. Demography,40(3), 521–542.

Keister, L. A. (2004). Race, family structure, and wealth: The effect of childhood family on adult asset ownership. Sociological Perspectives,47(2), 161–187.

Keister, L. A. (2007). Upward wealth mobility: Exploring the Roman Catholic advantage. Social Forces,85(3), 1195–1225.

Keister, L. A. (2008). Conservative protestants and wealth: How religion perpetuates asset poverty. American Journal of Sociology,113(5), 1237–1271.

Killewald, A. (2013). Return to being black, living in the red: A race gap in wealth that goes beyond social origins. Demography,50(4), 1177–1195.

Klesment, M., & van Bavel, J. (2017). The reversal of the gender gap in education, motherhood, and women as main earners in Europe. European Sociological Review,33, 465–481.

Lawson, D. W., & Mace, R. (2009). Trade-offs in modern parenting: A longitudinal study of sibling competition for parental care. Evolution and Human Behavior,30(3), 170–183.

Lawson, D. W., Makoli, A., & Goodman, A. (2013). Sibling configuration predicts individual and descendant socioeconomic success in a modern post-industrial society. PLoS ONE,8(9), e73698.

Leopold, T., & Schneider, T. (2011). Family events and the timing of intergenerational transfers. Social Forces,90(2), 595–616.

Mechoulan, S., & Wolff, F.-C. (2015). Intra-household allocation of family resources and birth order: Evidence from France using siblings data. Journal of Population Economics,28(4), 937–964.

Meng, X.-L., & Rubin, D. B. (1992). Performing likelihood ratio tests with multiply-imputed data sets. Biometrika,79, 103–111.

Mulder, C. H., & Wagner, M. (1998). First-time home-ownership in the family life course. A west German–Dutch comparison. Urban Studies,35, 687–713.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2017). OECD social and welfare statistics. Retrieved July 11, 2018 from https://stats.oecd.org/BrandedView.aspx?oecd_bv_id=socwel-data-en&doi=efd30a09-en.

Osmanowski, M., & Cardona, A. (2016). Is less more? Number of siblings and frequency of maternal activities with preschool children. Marriage & Family Review, 52, 742–763.

Park, H. (2008). Public policy and the effect of sibship size on educational achievement: A comparative study of 20 countries. Social Science Research,37(3), 874–887.

Parr, N. (2006). Do children from small families do better? Journal of Population Research,23(1), 1–25.

Paternoster, R., Brame, R., M, P., & Piquero, A. (1998). Using the correct statistical test for the equality of regression coefficients. Criminology,36, 859–866.

Pence, K. (2006). The role of wealth transformations: An application to estimating the effect of tax incentives on saving. The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy,5, 1–24.

Phillips, M. (1999). Sibship size and academic achievement: What we now know and what we still need to know: Comment on Guo and VanWey. American Sociological Review,64(2), 188–192.

Powell, B., & Steelman, L. C. (1993). The educational benefits of being spaced out: Sibship density and educational progress. American Sociological Review,58(3), 367–381.

Retherford, R. D., & Sewell, W. H. (1991). Birth order and intelligence: Further tests of the confluence model. American Sociological Review,56(2), 141–158.

Riphahn, R. T., & Serfling, O. (2005). Item non-response on income and wealth questions. Empirical Economics,30(2), 521–538.

Rodgers, J. L., Cleveland, H. H., van den Oord, E., & Rowe, D. C. (2000). Resolving the debate over birth order, family size, and intelligence. American Psychologist,55(6), 599–612.

Sandberg, J., & Rafail, P. (2014). Family size, cognitive outcomes, and familial interaction in stable, two-parent families: United States, 1997–2002. Demography,51(5), 1895–1931.

Schmidt, L. (2008). Risk preferences and the timing of marriage and childbearing. Demography,45(2), 439–460.

Sierminska, E. M., Frick, J. R., & G, M. M. (2010). Examining the gender wealth gap. Oxford Economic Papers,62, 669–690.

Spilerman, S. (2000). Wealth and Stratification Processes. Annual Review of Sociology,26(1), 497–524.

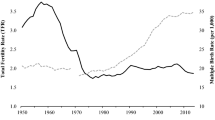

Statistisches Bundesamt. (2018). Zusammengefasste Geburtenziffer nach Kalenderjahren. Wiesbaden: Statistisches Bundesamt. Retrieved July 11, 2018 from https://www.destatis.de/DE/ZahlenFakten/GesellschaftStaat/Bevoelkerung/Geburten/Tabellen/GeburtenZiffer.html.

Steelman, L. C., Powell, B., Werum, R., & Carter, S. (2002). Reconsidering the effects of sibling configuration: Recent advances and challenges. Annual Review of Sociology,28, 243–269.

Szydlik, M. (2004). Inheritance and Inequality. Theoretical reasoning and empirical evidence. European Sociological Review,20, 31–45.

Trappe, H., Pollmann-Schult, M., & Schmitt, C. (2015). The rise and decline of the male breadwinner model. Institutional underpinnings and future expectations. European Sociological Review,31, 230–242.

Wagner, G. G., Frick, J. R., & Schupp, J. (2007). The German socio-economic panel study (SOEP): Scope, evolution and enhancements. Schmollers Jahrbuch,127(1), 139–170.

White, H. (1980). A heteroskedasticity-consistent covariance matrix estimator and a direct test for heteroskedasticity. Econometrica,48(4), 817–838.

Wiik, K. A. (2009). ‘You’d better wait!’. Socio-economic background and timing of first marriage versus first cohabitation. European Sociological Review, 25, 139–153.

Wilmoth, J., & Koso, G. (2002). Does marital history matter? Marital status and wealth outcomes among preretirement adults. Journal of Marriage and Family,64(1), 254–268.

Workman, J. (2017). Sibling additions, resource dilution, and cognitive development during early childhood. Journal of Marriage and Family,79(2), 462–474.

Yamokoski, A., & Keister, L. A. (2006). The wealth of single women: marital status and parenthood in the asset accumulation of young baby boomers in the United States. Feminist Economics,12(1–2), 167–194.

Zajonc, R. B., & Markus, G. B. (1975). Birth order and intellectual development. Psychological Review,82(1), 74–88.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Marita Jacob, Reinhard Schunck, seminar participants at the University of Cologne and University of Duisburg-Essen and participants at the ECSR Workshop “Demography and Inequality” for helpful comments on an earlier version of the manuscript. All errors remain those of the author. The computer code for the empirical analysis is available at https://osf.io/s62ed/.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

The informed consent of the interview participants was acquired by the SOEP and BHPS survey teams. The data are available through DIW Berlin and the UK Data Archive.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lersch, P.M. Fewer Siblings, More Wealth? Sibship Size and Wealth Attainment. Eur J Population 35, 959–986 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-018-09512-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-018-09512-x