Abstract

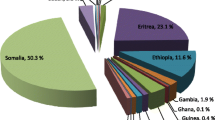

Female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C) is a rising issue in western societies as a consequence of international migration. Our paper presents demography-driven projections of female flows with FGM/C from each practicing country to each EU28 member state for the 3 sub-periods 2016–2020, 2021–2025, and 2026–2030, with the aim of supporting resource planning and policy making. According to our projections, the EU28 countries will receive a flow of around 400,000 female migrants between 2016 and 2020, and around 1.3 million female migrants between 2016 and 2030 from FGM/C practicing countries. About one-third of them, corresponding to an estimated 127,000 between 2016 and 2020, and more than 400,000 between 2016 and 2030 will have undergone FGM/C before migration. Among these female flows, slightly more than 20% is expected to be made up of girls aged 0–14. According to the expected age at arrival, 20% of these girls are expected to have already undergone FGM/C, while slightly less than 10% are to be considered potentially at risk of undergoing FGM/C after migration. As the number of women with FGM/C in Europe is expected to rise at quite a fast rate, it is important to act timely by designing targeted interventions and policies at the national and at the European level to assist cut women and protect children. Such measures are particularly compelling in France, Italy, Spain, UK, and Sweden that are expected to be the most affected countries by migration from FGM/C practicing countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Abdulcadir, J., Rodriguez, M. I., & Say, L. (2015). Research gaps in the care of women with female genital mutilation: An analysis. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 122(3), 294–303.

Adepoju, A. (2011). Reflections on international migration and development in sub-Saharan Africa. African Population Studies, 25(2), 298–319.

African Union. (2006). African common position on migration and development. Banjul, The Gambia: African Union. Internet resource. Accessed Nov 2016. http://www.un.org/en/africa/osaa/pdf/au/cap_migrationanddev_2006.pdf.

Ahmed, S. A., Cruz, M., Go, D. S., Maliszewska, M., & Osorio-Rodarte, I. (2014). How significant is Africa’s demographic dividend for its future growth and poverty reduction? World Bank policy research working paper 7134. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Andro, A., Cambois, E., & Lesclingand, M. (2014). Long-term consequences of female genital mutilation in a European context: Self perceived health of FGM women compared to non-FGM women. Social Science and Medicine, 106, 177–184.

Berg, R., & Denison, E. (2012). Does female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C) affect women’s sexual functioning? A systematic review of the sexual consequences of FGM/C. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 9(1), 41–56.

Berg, R., & Denison, E. (2013). A tradition in transition: Factors perpetuating and hindering the continuance of female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C) summarized in a systematic review. Health Care for Women International, 34(10), 837–859.

Bijak, J., Disney, G., & Wisniowski, A. (2015). How to forecast international migration. CPC briefing paper 28. Southampton: ESRC Centre for Population Change.

Blangiardo, G. C. (2014). Scenarios of migration inflows to the EU-28 members according to push factors related to the labor market in the countries of origin. KING project—demography unit overview paper no 11, Oct 2014.

Bossard, L. (2009). The future of international migration to OECD countries regional note West Africa. Paris: OECD.

Boswell, C. (2002). Addressing the causes of migratory and refugee movements: The role of the European Union. New issues in refugee research. Working paper no. 73. Geneva: UNHCR.

Brown, C., Beecham, D., & Barrett, H. (2013). The applicability of behaviour change in intervention programmes targeted at ending female genital mutilation in the EU: Integrating social cognitive and community level approaches. Obstetrics and Gynecology International Article ID 324362, 12 p.

Cappon, S., L’Ecluse, C., Clays, E., Tency, I., & Leye, E. (2015). Female genital mutilation: Knowledge, attitude and practices of Flemish midwives. Midwifery, 31(3), e29–e35.

Chibber, R., El-Saleh, E., & El-Harmi, J. (2011). Female circumcision: Obstetrical and psychological sequelae continues unabated in the 21st century. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine, 24(6), 833–836.

Clemens, M. A. (2014). Does development reduce migration? In R. B. L. Lucas (Ed.), International handbook on migration and economic development. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd.

Cross, C., Gelderblom, D., Roux, N., & Mafukidze, J. (2006). Views on migration in Sub-Saharan Africa. In Proceedings of an African migration alliance workshop. Cape Town: HSCR Press.

Czaika, M., & De Haas, H. (2012). The role of internal and international relative deprivation in global migration. Oxford Development Studies, 40(4), 423–442.

Czaika, M., & Vothknecht, M. (2012). Migration as cause and consequence of aspirations DEMIG project paper 13. Oxford: IMI Working Papers Series.

De Haas, H. (2008a). Migration and development. A theoretical perspective. IMI working paper no. 9. Oxford: IMI. https://www.imi.ox.ac.uk/pdfs/wp/wp-09-08.pdf. Accessed Nov 2016.

De Haas, H. (2008b). The myth of invasion: The inconvenient realities of African migration to Europe. Third World Quarterly, 29(7), 1305–1322.

De Haas, H. (2010). Migration transitions: A theoretical and empirical inquiry into the developmental drivers of international migration, DEMIG, working paper no. 24, International Migration Institute, University of Oxford.

De Haas, H. (2011). The determinants of international migration. Conceptualising policy, origin and destination effects DEMIG project paper 2. Oxford: IMI Working Papers Series.

DHS. (2015). The DHS program. Tool and resources. Resource document. http://www.dhsprogram.com/. Accessed Nov 2016.

EIGE—European Institute for Gender Equality. (2013a). Female genital mutilation in the European Union and Croatia Vilnius: EIGE.

EIGE—European Institute for Gender Equality. (2013b). Good practices in combating female genital mutilation Vilnius: EIGE.

EIGE—European Institute for Gender Equality. (2015). Estimation of girls at risk of female genital mutilation in the European Union: EIGE.

European Parliament. (2014). European parliament resolution of 6 February 2014 on the commission communication entitled ‘Towards the elimination of female genital mutilation’. Resource document. European Parliament. http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?type=TA&reference=P7-TA-2014-0105&language=EN#def_1_10. Accessed Nov 2016.

Eurostat. (2017). Database. Internet resource. http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database. Accessed 6 Sep 2017.

Fargues, P. (2008). Emerging demographic patterns across the mediterranean and their implications for migration through 2030. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute.

Fargues, P. (2011). International migration and the demographic transition: A two-way interaction. International Migration Review, 45, 588–614.

Farina, P., & Ortensi, L. E. (2014). The mother to daughter transmission of female genital cutting in emigration as evidenced by Italian survey data. Genus, 70(2–3), 111–137.

Fassmann, H. (2014). Estimating migration potential: Egypt, Morocco and Turkey. In M. Bommes, H. Fassmannn, & W. Sievers (Eds.), Migration from the Middle East and North Africa to Europe. Past developments, current status and future potentials. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Fassmann, H., & Sievers, W. (2014). Introduction. In M. Bommes, H. Fassmannn, & W. Sievers (Eds.), Migration from the Middle East and North Africa to Europe. Past developments, current status and future potentials. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Flahaux, M.-L., & De Haas, H. (2016). African migration: Trends, patterns, drivers. Comparative Migration Studies, 4, 1. doi:10.1186/s40878.

Fleury, A. (2016). Understanding women and migration: A literature review. KNOMAD working paper 8. New York: The World Bank.

Foldès, P., Cuzin, B., & Andro, A. (2012). Reconstructive surgery after female genital mutilation: A prospective cohort study. The Lancet, 380, 134–141.

Gilardoni, G., D’Odorico, M., & Carrrillo, D. (2015). KING. Knowledge for INtegration governance. Evidence on migrants’ integration in Europe. Milan: ISMU.

Hatton, T. J., & Williamson, J. G. (2003). Demographic and economic pressure on emigration out of Africa. The Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 105, 465–486.

Hugo, G. (2007). Indonesia’s labor looks abroad. MPI—Migration Information Source. http://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/indonesias-labor-looks-abroad. Accessed Nov 2016.

IMI [International Migration Institute], & RMMS [Regional Mixed Migration Secretariat]. (2012). Global migration futures. Using scenarios to explore future migration in the Horn of Africa and Yemen. Project report. November 2012. Oxford & Nairobi: IMI & RMMS. https://www.imi.ox.ac.uk/publications/global-migration-futures-using-scenarios-to-explore-future-migration-in-the-horn-of-africa-yemen. Accessed Nov 2016.

IOM. (2014). Supporting the abandonment of female genital mutilation in the context of migration. Geneva: IOM.

ISMU. (2015). KING—Knowledge for INtegration governance. Resource document. ISMU. http://king.ismu.org/. Accessed Nov 2016.

Jamie, F. O. M. (2013). Gender and migration in Africa: Female Ethiopian migration in post-2008. Sudan Journal of Politics and Law, 6(1), 186–192.

Johnsdotter, S., Kontiemoussa, A. R., & Essen, B. (2009). Never my daughters’: A qualitative study regarding attitude change toward female genital cutting among Ethiopian and Eritrean families in Sweden. Health Care Women International, 30(1–2), 114–133.

Johnson, K., Grant, M., Khan, S., Moore, Z., Armstrong, A., & Sa, Z. (2009). Fieldwork-related factors and data quality in the demographic and health surveys program., DHS analytical studies no. 19 Calverton: ICF Macro.

Kaplan-Marcusan, A., Torán-Monserrat, P., Moreno-Navarro, J., Castany Fàbregas, M. J., & Muñoz-Ortiz, L. (2009). Perception of primary health professionals about female genital mutilation: From healthcare to intercultural competence. BMC Health Services Research, 9, 11.

Leye, E., Mergaert, L., Arnaut, C., & O’Brien Green, S. (2014). Towards a better estimation of prevalence of female genital mutilation in the European Union: Interpreting existing evidence in all EU member states. Genus, LXX(1), 99–121.

Leye, E., Powell, R. A., Nienhuis, G., Claeys, P., & Temmerman, M. (2006). Health care in Europe for women with genital mutilation. Health Care for Women International, 27, 362–378.

Leye, E., Ysebaert, I., Deblonde, J., Claeys, P., Vermeulen, G., Jacquemyn, Y., et al. (2008). Female genital mutilation: Knowledge, attitudes and practices of Flemish gynaecologists. The European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care, 13(2), 182–190.

Lindstrom, D. P., & Ramírez, A. (2010). Pioneers and followers: Migrant selectivity and the development of US migration streams in latin America. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 630, 53–77.

Lucas, R. E. B. (2006). Migration and economic development in Africa: A review of evidence. Journal of African Economies, volume 15, AERC supplement, 2, 337–395.

Mackie, G., & Lejeune, J. (2009). Social dynamics of abandonment of harmful practices: A new look at the theory. Florence: UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre.

Martin, P. L. (2009). Demographic and economic trends: Implications for international mobility. Human development research paper 2009/19 UNDP.

Martin, P. L., & Taylor, J. E. (1996). The anatomy of a migration hump. In J. E. Taylor (Ed.), Development strategy, employment, and migration: Insights from models (pp. 43–62). Paris: OECD.

Massey, D. S., Arango, J., Hugo, G., Kouaouci, A., Pellegrino, A., & Taylor, J. E. (2005). Worlds in motion. Understanding international migration at the end of the millennium. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

McArthur, J. W. (2014). Pushing the employment frontiers for Africa’s rural and urban youth in Brookings Africa growth initiative-foresight Africa. Top priorities for the continent in 2014. Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution.

McKenzie, D., & Rapoport, H. (2010). Self-selection patterns in Mexico-US migration: The role of migration networks. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 92(4), 811–821.

Morison, L., Dirir, A., Elmi, S., Warsame, J., & Dirir, S. (2004). How experience and attitudes relating to female circumcision vary according to age on arrival in Britain: A study among young Somalis in London. Ethnicity and Health, 9(1), 75–100.

Mukherjee, A. (2014). Female genital mutilation in Egypt (Compared to Burkina Faso) scholarly horizons: University of Minnesota. Morris Undergraduate Journal, 1(2), 1–24.

Naudé, W. (2010). The determinants of migration from Sub-Saharan African countries. Journal of African Economies, 19(3), 330–356.

NRC [National Research Council]. (2000). Beyond six billion. Forecasting the world’s population. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Nyberg–Sørensen, N., Van Hear, N., & Engberg-Pedersen, P. (2002). The migration-development nexus evidence and policy options state-of-the-art overview. International Migration, 40(5), 3–7.

OECD. (2009). The future of international migration to OECD countries. Paris: OECD Publishing.

O’Neill, B. C., Balk, D., Brickman, M., & Ezra, M. (2001). A guide to global population projections. Demographic Research, 4, 203–288.

Orchid Project. (2012). Female genital cutting in Egypt. Resource document. The orchid project. http://orchidproject.org/female-genital-cutting-in-egypt/. Accessed Nov 2016.

Ortensi, L. E., Farina, P., & Menonna, A. (2015). Improving estimates of the prevalence of female genital mutilation/cutting among migrants in Western countries. Demographic Research, 32, 543–562.

Page, J. (2012). Youth, jobs, and structural change: Confronting Africa’s “Employment Problem”. African Development Bank Group working paper series no. 155. Tunis: African Development Bank.

Powell, R. A., Leye, E., Jayakody, A., Mwangi-Powell, F. N., & Morison, L. (2004). Female genital mutilation, asylum seekers and refugees: The need for an integrated European Union agenda. Health Policy, 70, 151–162.

PRB—Population Reference Bureau. (2001). Understanding and using population projections. Measure communication policy brief. Resource document. PRB. http://www.prb.org/pdf/UnderStndPopProj_Eng.pdf. Accessed Nov 2016.

PRB—Population Reference Bureau. (2009). Population reference bureau: World population data sheet 2009. Washington, DC: Population Reference Bureau Website.

Ratha, D., Mohapatra, S., Özden, C., Plaza, S., Shaw, W., & Shimeles, A. (2011). Leveraging migration for Africa remittances, skills, and investments. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Raymer, J., & Rogers, A. (2008). Applying model migration schedules to represent age-specific migration flows. In J. Raymer & F. Willekens (Eds.), International migration in Europe. Data, models and estimates. Chichester: Wiley.

Reig-Alcaraz, M., Siles-González, J., & Solano-Ruiz, C. (2016). A mixed-method synthesis of knowledge, experiences and attitudes of health professionals to female genital mutilation. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 72(2), 245–260.

Reynolds, R. R. (2006). Professional Nigerian women, household economy, and immigration decisions. International, 44(5), 167–188.

Rogers, A., & Castro, L. (1981). Age patterns of migration: Cause-specific profiles. In A. Rogers (Ed.), Advances in multiregional demography (pp. 125–159). Luxemburg: International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Schoumaker, B., Flahaux, M. L., Schans, D., Beauchemin, C., Mazzucato, V., & Sakho, P. (2015). Changing patterns of African Migration: A comparative analysis. In C. Beauchemin (Ed.), Migration between Africa and Europe: Trends, factors and effects. New-York: Springer.

Shaw, W. (2007). Migration in Africa: A Review of the economic literature on international migration in 10 countries. Development prospects group. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Spadavecchia, C. (2013). Migration from Sub-Saharan Africa to Europe: The role of highly skilled women. Sociología y tecnociencia/Sociology and Technoscience, 3(3), 96–116.

Sudan Federal Ministry of Health and Central Bureau of Statistics. (2012). Sudan household and health survey. National report. Khartoum: Federal Ministry of Health and Central Bureau of Statistics.

Surico, D., Amadori, R., Gastaldo, L. B., Tinelli, R., & Surico, N. (2015). Female genital cutting: A survey among healthcare professionals in Italy. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 35(4), 393–396.

Thomas, K. J. A., & Logan, I. (2012). African female immigration to the United States and its policy implications. Canadian Journal of African Studies, 46(1), 87–107.

UNFPA. (2015). Demographic perspectives on female genital mutilation. New York: UNFPA.

UNHCR. (2014). Too much pain: Female genital mutilation & asylum in the European union—A statistical update. Internet resource. UNHCR. http://www.refworld.org/pdfid/5316e6db4.pdf. Accessed Nov 2016.

UNICEF. (2013). Female genital mutilation/cutting: A statistical overview and exploration of the dynamics of change. New York: United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF).

UNICEF. (2014a). Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS). Statistics and monitoring. Resource document. UNICEF. http://www.unicef.org/statistics/index_24302.html. Accessed 24 Sep 2015. Accessed Nov 2016.

UNICEF. (2014b). Female genital mutilations/cutting: what might the future hold?. New York: United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF).

UNICEF. (2016). Female genital mutilation/cutting: A global concern. New York: United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF).

Union, African. (2011). Decisions adopted during the 17th African Union Summit, 23 June–1 July 2011. Malabo: African Union.

Van Baelen, L., Ortensi, L. E., & Leye, E. (2016). Estimates of first-generation women and girls with female genital mutilation in the European Union, Norway and Switzerland. The European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care. doi:10.1080/13625187.2016.1234597.

Vogler, M., & Rotte, R. (2000). The effects of development on migration: Theoretical Issues and new empirical evidence. Journal of Population Economics, 13, 485–508.

WHO. (2008). Eliminating female genital mutilation. An interagency statement. New York: WHO.

Wouterse, F., & van den Berg, M. (2011). Heterogeneous migration flows from the Central Plateau of Burkina Faso: The role of natural and social capital. The Geographical Journal, 177(4), 357–366.

Yaro, J. A. (2008). Migration in West Africa: Patterns, issues and challenges. Centre for Migration Studies. Legon: University of Ghana.

Yoder, P. S., & Shanxiao, W. (2013). Female genital cutting: The interpretation of recent DHS sata. DHS comparative reports no. 33. Calverton: ICF International.

Yoder, P. S., Wangs, S., & Johansen, E. (2013). Estimates of female genital mutilation/cutting in 27 African Countries and Yemen. Studies in Family Planning, 44(2), 189–204.

Zaidi, N., Khalil, A., Roberts, C., & Browne, M. (2007). Knowledge of female genital mutilation among healthcare professionals. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 27(2), 161–164.

Zurynski, Y., Sureshkumar, P., Phu, A., & Elliott, E. (2015). Female genital mutilation and cutting: A systematic literature review of health professionals’ knowledge, attitudes and clinical practice. BMC International Health and Human Rights, 15, 32.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ortensi, L.E., Menonna, A. Migrating with Special Needs? Projections of Flows of Migrant Women with Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting Toward Europe 2016–2030. Eur J Population 33, 559–583 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-017-9426-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-017-9426-4