Abstract

There are some necessary conditions on causal relations that seem to be so trivial that they do not merit further inquiry. Many philosophers assume that the requirement that there could be no temporal gaps between causes and their effects is such a condition. Bertrand Russell disagrees. In this paper, an in-depth discussion of Russell’s argument against this necessary condition is the centerpiece of an analysis of what is at stake when one accepts or denies that there can be temporal gaps between causes and effects. It is argued that whether one accepts or denies this condition, one is implicated in taking on substantial and wide-ranging philosophical positions. Therefore, it is not a trivial necessary condition of causal relations and it merits further inquiry.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Baldwin, J. M. (Ed.). (1901). Dictionary of philosophy and psychology. London: Macmillan and Co., Limited.

Beauchamp, T., & Rosenberg, A. (1981). Hume and the problem of causation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Brand, M. (1980). Simultaneous causation. In P. van Inwagen (Ed.), Time and cause (pp. 137–153). Dordrecht: D. Reidel Publishing Company.

Chakravartty, A. (2005). Causal realism: Events and processes. Erkenntnis, 63, 7–31.

Chalmers, D. J. (2002). Does conceivability entail possibility? In T. Gendler & J. Hawthorne (Eds.), Conceivability and Possibility (pp. 145–200). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dainton, B. (2010). Time and space. Durham: Acumen Publishing Limited.

Dasgupta, S. (2016). Metaphysical rationalism. Noûs, 50, 379–418.

Dummett, M. (2000). Is time a continuum of instants? Philosophy, 75, 497–515.

Dummett, M. (2003). How should we conceive of time? Philosophy, 78, 387–396.

Dummett, M. (2005). Hume’s atomism about events: A response to Ulrich Meyer. Philosophy, 80, 141–144.

Ehring, D. (1985). Simultaneous causation and causal chains. Analysis, 45, 98–102.

Ehring, D. (1987). Non-simultaneous causation. Analysis, 47, 28–32.

Field, H. (2003). Causation in a physical world. In M. Loux & D. Zimmerman (Eds.), Oxford handbook of metaphysics (pp. 435–460). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hitchcock, C. (2007). What Russell got right. In H. Price & R. Corry (Eds.), Causation, physics, and the constitution of reality: Russell’s republic revisited (pp. 45–65). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Huemer, M., & Kovitz, B. (2003). Causation as simultaneous and continuous. The Philosophical Quarterly, 53, 556–565.

Hume, D. (1999). An enquiry concerning human understanding. In T. L. Beauchamp (Ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hume, D. (2000). A treatise of human nature. In D. F. Norton & M. J. Norton (Eds.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kant, I. (1998). Critique of pure reason (P. Guyer & A. Wood, Trans.). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Kistler, M. (2002). Causation in contemporary analytical philosophy. In C. Esposito & P. Porro (Eds.), La Causalità-La Causalité-Die Kausalität-Causality (pp. 635–668). Turnhout: Brepols.

Kleinschmidt, S. (2013). Reasoning without the principle of sufficient reason. In T. Goldschmidt (Ed.), The puzzle of existence: Why is there something rather than nothing? (pp. 47–79). New York: Routledge.

Kline, A. D. (1980). Are there cases of simultaneous causation? In PSA: Proceedings of the biennial meeting of the philosophy of science association 1980 (pp. 292–301).

Kline, A. D. (1982). The ‘established maxim’ and causal chains. In PSA: Proceedings of the biennial meeting of the philosophy of science association 1982 (pp. 65–74).

Kline, A. D. (1985). Humean causation and the necessity of temporal discontinuity. Mind, 94, 550–556.

Lewis, D. (1973). Causation. Journal of Philosophy, 70, 556–567.

Lewis, D. (Ed.) (1986). Causation. In: Philosophical papers, Volume II (pp. 159–213). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lipkind, D. (1979). Russell on the notion of cause. Canadian Journal of Philosophy, 9, 701–720.

Lorente, M. (1976). Bases for a discrete special relativity. International Journal of Theoretical Physics, 15, 927–947.

Lorente, M. (1986a). Space-time groups for the lattice. International Journal of Theoretical Physics, 25, 55–65.

Lorente, M. (1986b). Physical models on discrete space and time. In B. Gruber & R. Lenczewski (Eds.), Symmetries in science II. Boston: Springer.

Lorente, M. (1993). Representations of classical groups on the lattice and its application to the field theory on discrete space-time. In B. Gruber (Ed.), Symmetries in science VI. Boston: Springer.

Ma, C. K. W. (1999). Causation & physics. Retrieved December 11, 2015, from arXiv:quant-ph/9906061.

Mackie, J. L. (1974). The cement of the universe. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Mellor, D. H. (1995). The facts of causation. London: Routledge Press.

Meyer, U. (2005). Dummett on the time-continuum. Philosophy, 80, 135–140.

Noordhof, P. (1999). Probabilistic causation, preemption and counterfactuals. Mind, 108, 95–125.

Paul, L. A., & Hall, N. (2013). Causation: A user’s guide. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Peirce, C. (1933). The logic of quantity. In C. Hartshorne & P. Weiss (Eds.), Collected papers of Charles Sanders Peirce (Vol. IV, pp. 85–152). Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Price, H. (2014). Where would we be without counterfactuals? In M. C. Galavotti, D. Dieks, W. J. Gonzalez, S. Hartmann, T. Uebel, & M. Weber (Eds.), New directions in the philosophy of science (pp. 589–607). Cham: Springer.

Ross, D., & Spurrett, D. (2007). Russell’s thesis revisited. The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 58, 45–76.

Russell, B. (1912). On the notion of cause. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 13, 1–26.

Shoemaker, S. (1969). Time without change. The Journal of Philosophy, 66, 363–381.

Smith, B., & Varzi, A. (2000). Fiat and bona fide boundaries. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 60, 401–420.

Trenholme, R. (1975). Causation and necessity. The Journal of Philosophy, 72, 444–465.

Varzi, A. (1997). Boundaries, continuity, and contact. Noûs, 31, 26–58.

Waterlow, S. (1974). Backwards causation and continuing. Mind, 78, 372–387.

Watkins, E. (2005). Kant and the metaphysics of causality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Weaver, C. G. (2013). A Church–Fitch proof for the universality of causation. Synthese, 190, 2749–2772.

Weber, Z., & Cotnoir, A. J. (2015). Inconsistent boundaries. Synthese, 192, 1267–1294.

Yablo, S. (1997). Wide causation. Philosophical Perspectives, 11, 251–281.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Sara Bernstein, Anjan Chakravartty, Xavi Lanao, Samuel Newlands, Caleb Ontiveros, Mark Puestohl, Sebastian Murgueitio Ramirez, Norman Sieroka, and Jeremy Steeger for discussion, guidance, and helpful comments on earlier drafts.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Russell’s Overall Argument

Appendix: Russell’s Overall Argument

Show: ~NTG

-

P1.

~~NTG. [assumption for reductio proof]

-

P2.

Either both causes and effects are instantaneous, or not. [disjunction introduction]

-

P3.

Both causes and effects are instantaneous. [assumption for conditional proof]

-

P4.

If both causes and effects are instantaneous, then there is a duration between them.

-

P5.

If there is a duration between causes and effects, then ~NTG.

-

P6.

~NTG. [P3, P4, P5, modus ponens]

-

P7.

If both causes and effects are instantaneous, then ~NTG. [P3, P6, conditional proof]

-

P8.

It is not the case that both causes and effects are instantaneous. [P1, P7, modus tollens]

-

P9.

Causes are not instantaneous. [P8, Baldwin’s definition]

-

P10.

Either causes are processes that undergo change over time, or causes are static through time and do not change. [P9]

-

P11.

Causes are processes that undergo change over time. [assumption for reductio proof]

-

P12.

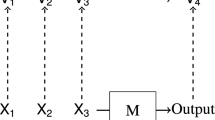

If causes are processes that undergo change over time, then they have temporal parts.

-

P13.

Causality is universal.

-

P14.

If causes have temporal parts, causality is universal, and NTG, then each temporal part of a cause could only be caused by the temporal part prior to it and could only cause the temporal part posterior to it.

-

P15.

If each temporal part of a cause could only be caused by the temporal part prior to it and could only cause the temporal part posterior to it, then only the last temporal part of the cause could be the cause of the first temporal part of the effect.

-

P16.

There could not be a last temporal part of a cause.

-

P17.

Only the last temporal part of a cause could be the cause of the first temporal part of its effect, and there could not be a last temporal part of a cause. [P11, P12, P13, P14, P15, modus ponens, P16, conjunction introduction]

-

P18.

There are no causes that are processes that undergo change over time. [P17]

-

P19.

There are causes that are processes that undergo change over time.

-

P20.

It is not the case that causes are processes that undergo change over time. [P11, P18, P19, reductio proof]

-

P21.

Causes are static and do not change over time. [P10, P20, disjunctive syllogism]

-

P22.

If causes are static and do not change over time, then there are no causes in nature and there are no explanations of why effects occur when they do.

-

P23.

It is not the case that there are no causes in nature and there are no explanations of why effects occur when they do.

-

P24.

It is not the case that causes are static and do not change over time. [P22, P23, modus tollens]

-

P25.

~NTG [P1, P21, P24, reductio proof]

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Clay, G. Russell and the Temporal Contiguity of Causes and Effects. Erkenn 83, 1245–1264 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10670-017-9939-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10670-017-9939-6