Abstract

What distinguishes indicative conditionals from subjunctive conditionals, according to one popular view, is that the so-called Adams’ thesis holds for the former kind of conditionals but the so-called Skyrms’ thesis for the latter. According to a plausible metaphysical view, both conditionals and chances supervene on non-modal facts. But since chances do not supervene on facts about particular events but facts about event-types, the past as well as the future is chancy. Some philosophers have worried that this metaphysical view is incompatible with the aforementioned view on the probability of conditionals. This paper however shows that there is no need to worry, as these views can all be simultaneously satisfied within the so-called Multidimensional Possible World Semantics for conditionals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

What I am calling ‘subjunctive conditionals’, some (e.g. David Lewis) call ‘counterfactuals’. Neither term is perfect, as Lewis (1986a) points out, since the conditionals in question are not always expressed in the subjunctive mood, nor are their antecedents always assumed to be false. I will classify conditionals by their truth conditions rather than surface grammar, and like e.g. Lewis (1986a) and Hannes Leitgeb (2012a), I will assume that subjunctive conditionals and counterfactual conditionals are the same type of conditional.

The view is named after David Hume, “the greater denier of necessary connections” (Lewis 1987: ix).

Or, on Lewis’ view, two worlds like ours (see e.g. Lewis 1987). For the present purposes, I will treat supervenience theses as being either necessarily true or necessarily false.

Various empirical and metaphysical objections have been raised against Humean Supervenience. I will not try to defend the view against these objections, but rather focus on trying to make it compatible with the aforementioned view on the probability of conditionals.

Hoefer and Frigg’s Humean theory of chance has various advantages over Lewis’. For instance, the former can make sense of the idea that there can be non-trivial objective chances in deterministic systems, which is an idea that seems to have recently been gaining increasing support. For the present purposes, however, the important difference between Hoefer’s and Lewis’ theories is that on the latter view, only the future can be chancy (see e.g. Lewis 1980), but both past and future events can be chancy on Hoefer and Frigg’s theory.

This terminology is borrowed from (Bradley 2012).

I will follow the terminology in (Bradley 2012) and thus speak of vectors rather than n-tuples.

As the above table indicates, the MD-semantics entails the truth of the Conditional Excluded Middle (CEM); that is, the principle that for all sentences A and B, either \(A\rightarrow B\) or \(A\rightarrow\neg B\) is true. For given the ordinary excluded middle, either B or \(\neg B\) is true at each counter-actual A-world.

What counts as sufficient should for instance depend on the context of utterance, the kind of sentences involved, etc.

This assumption should be restricted to conditionals with consistent antecedents.

See (Gundersen 2004) for an argument that even the weak centring condition is counterintuitive.

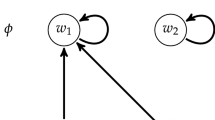

Since it follows from centring, like the discussion above illustrates, that \(\mathcal{P}r(w_{1}\mid w_{1})=1\) and \(\mathcal{P}r(w_{2}\mid w_{1})=0, \) an agent’s state of uncertainty given centring can be represented as:

W 1

W 2

W 1

\(\mathcal{P}(w_{1})\)

0

W 2

0

\(\mathcal{P}(w_{2})\)

W 3

\(\mathcal{P}(w_{3}).\mathcal{P}r(w_{1}\mid w_{3})\)

\(\mathcal{P}(w_{3}).\mathcal{P}r(w_{2}\mid w_{3})\)

W 4

\(\mathcal{P}(w_{4}).\mathcal{P}r(w_{1}\mid w_{4})\)

\(\mathcal{P}(w_{4}).\mathcal{P}r(w_{2}\mid w_{4})\)

The example of Oswald and Kennedy, discussed above, shows that AT does not in general hold for subjunctive conditionals. Here is another example: The Aragawa restaurant in Tokyo is apparently the most expensive restaurant in the world. Hence, the conditional probability that you are rich, given that he frequently dine at Aragawa, is quite high. And so is the probability of the indicative conditional: ‘If you frequently dine at Aragawa, then you are rich’. But the same is not true of the subjunctive conditional: ‘If you were to frequently dine at Aragawa, you would be rich.’ In fact, if you are like most people, frequently dining at Aragawa would bankrupt you!

In addition to Adams, Richard Jeffrey (1964) and Robert Stalnaker (1970) were prominent early proponents of some version of AT. Adams himself did actually not accept AT in the form that I have been discussing it. Rather, according to Adams, P in AT should not be interpreted as measuring the probability of a sentence’s truth, but rather something like its degree of assertibility (The same can be said about how Brian Skyrms interpreted P in what I am calling ‘Skyrms’ thesis’).

According to SC: \(P(A\,\mapsto\, B) \geq P(A\wedge B), \) so given AT: P(A ∧ B)/P(A) ≥ P(A ∧ B). And that holds whenever \(0 < P(A)\leq 1, \) since then P(A).P(A ∧ B) ≤ P(A ∧ B). According to WC: \(P(A\supset B) \geq P(A\,\mapsto\, B), \) so given AT: \( P(A\supset B)=P(A\wedge B)+P(\neg A) \geq P(A\wedge B)/P(A). \) It is easy to see that this inequality holds when P(A ∧ B) = 0. Now assume that \(P(A\wedge B) > 0. \) The inequality we want to prove can be written as \(P(\neg A).P(A)+P(A).P(A\wedge B)\geq P(A\wedge B); \) and hence (since \(P(A\wedge B) > 0\)), as \(P(\neg A).P(A)/P(A\wedge B)+P(A\wedge B).P(A)/P(A\wedge B)\geq 1; \) which is equivalent to \(P(\neg A).P(A)/P(A\wedge B)+P(A)\geq 1. \) This last inequality holds if and only if: \(P(\neg A).P(A)/P(A\wedge B)\geq P(\neg A). \) To see that this holds, notice that it can be written as \(P(\neg A).P(A)\geq P(\neg A).P(A\wedge B)\) which is true since P(A) ≥ P(A ∧ B).

ST implies that two worlds cannot differ in counterfactuals without differing in chances; in other words, counterfactual conditionals supervene on chances. But then if chances supervene on facts, counterfactuals supervene on facts (since supervenience is a transitive relation). So if conditionals in general do not supervene on facts, then, given Skyrms’ thesis, chances cannot supervene on facts either.

Given the above assignments of worlds to sentences, we have \(B=\{\langle w_{3}, w_{1}\rangle \}\bigcup\{\langle w_{3}, w_{2}\rangle \}\bigcup\{\langle w_{1}, w_{1}\rangle \}\bigcup\{\langle w_{1}, w_{2}\rangle \}. \) But the conditional \(A\,\mapsto\, B\) is neither true in \(\langle w_{3}, w_{2}\rangle \) nor \(\langle w_{1}, w_{2}\rangle \) so as long as these have a positive probability, then \(P(A\,\mapsto\, B\mid B)\not=1. \) Now of course, given centring, which I have suggested we should accept for indicative conditionals, \(P(\langle w_{1}, w_{2}\rangle )=0\). But we have no justification for assuming that \(P(\langle w_{3}, w_{2}\rangle )=0. \) Hence, given the MD-semantics, we cannot assume that \(P(A\,\mapsto\, B\mid B)=1. \) (This means that \(P(A\,\mapsto\, B\mid B)\not=P(B\mid A\wedge B). \) Hence, AT only holds for simple indicative conditionals.)

In “A Lewisian Trilemma” (forthcoming in Ratio) I prove that the latter supervenience relation is implied by Strong and Weak Centring.

References

Adams, E. W. (1975). The logic of conditionals. Dordrecht: D. Reidel.

Bradley, R. (2011). Conditionals and supposition-based reasoning. Topoi, 30(1), 39–45.

Bradley, R. (2012). Multidimensional possible-world semantics for conditionals. Philosophical Review, 121(4), 539–571.

Frigg, R. & Hoefer, C. (ta.). The best humean system for statistical mechanics. Erkenntnis, (Forthcoming).

Gundersen, L. B. (2004). Outline of a new semantics for counterfactuals. Pacific Philosophical Quarterly, 85(1), 1–20.

Hájek, A. & Hall, N. (1994). The hypothesis of the conditional construal of conditional probability. In Probability and conditionals: Belief revision and rational decision. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hoefer, C. (2007). The third way on objective probability: A sceptic’s guide to objective chance. Mind, 116(463), 449–496.

Jeffrey, R. (1964). If. The Journal of Philosphy, 61(21), 702–1.

Joyce, J. (1999). The foundations of causal decision theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Leitgeb, H. (2012). A probabilistic semantics for counterfactuals. Part A. The Review of Symbolic Logic, 5(1), 26–84.

Leitgeb, H. (2012). A probabilistic semantics for counterfactuals. Part B. The Review of Symbolic Logic, 5(1), 85–121.

Lewis, D. (1976). Probabilities of conditionals and conditional probabilities. Philosophical Review, 85(3), 297–315.

Lewis, D. (1980). A subjectivist’s guide to objective chance. In Jeffrey, R. (Ed.), Studies in inductive logic and probability. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Lewis, D. (1986). Counterfactuals. Oxford: Blackwell (revised edition).

Lewis, D. (1986). Probabilities of conditionals and conditional probabilities II. Philosophical Review, 95(4), 581–589.

Lewis, D. (1987). Introduction. In Philosophical papers, Vol. 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lewis, D. (1994). Humean supervenience debugged. Mind, 103(412), 473–490.

Ramsey, F. P. (1990/1929). General propositions and causality. In D. H. Mellor (Ed.), Philosophical papers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Skyrms, B. (1981). The prior propensity account of subjunctive conditionals. In W. L. Harper, R. Stalnaker & G. Pearce (Eds.), Ifs: Conditionals, belief, decision, chance, and time. Dordrecht: D. Reidel.

Stalnaker, R. (1970). Probability and conditionals. Philosophy of Science, 1(80–64), 23–42.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Richard Bradley and two referees for Erkenntnis for helpful comments on this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stefánsson, H.O. Humean Supervenience and Multidimensional Semantics. Erkenn 79, 1391–1406 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10670-014-9607-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10670-014-9607-z