Abstract

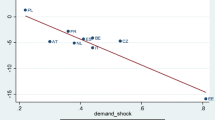

We explore the effects of EU-accession on firms in Central and Eastern Europe. We draw on trade theory and institutional reform literature to argue changes in both the perceived market structures and productivity distributions. Using firm level data from six waves of the World Bank’s Enterprise Survey between 2002 and 2013, we document a decreasing likelihood of higher market concentration as countries accede. We show changes in the firm level productivity distributions. EU-membership tends to a decrease the variance of productivity across firms, and shifts the distribution towards higher productivity levels. Less concentrated markets are associated with higher productivity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See http://ec.europa.eu/enlargement/countries/package/index_en.htm. Accessed on 22 June 2016.

The datasets, sampling procedures and the methodology used in the data collection are publicly available. See http://www.enterprisesurveys.org/. Accessed on 22 June 2016.

All datasets that were available on 13 October 2014 were used to consider the survey wave in 2013. Descriptive statistics are available in the supplementary material.

Melitz’ work has triggered a lot of research on internationally trading firms and trade gains (e.g., Helpman et al. 2004; Haskel et al. 2007). Yet, only few firms are internationally active. It remains unclear how the competitive environment of domestic firms is affected by openness, especially because there may be second order effects of (e.g., if domestic firms are affected by international value chains as suppliers or by competing against other firms that are part suppliers).

The questionnaires in 2002 and 2005 asked about the number of competitors in the local market for the main product line or service (q12ba). The given answer categories were “none”, “1–3” and “4 or more”. The question in the survey waves 2007 and 2009 was ‘How many competitors did this establishment’s main product/product line face?’ (e2). Possible answers were “none”, “one”, “2–5” and “more than 5”. The survey waves 2012 and 2013 contain a question about the number of competitors for the main product/service in the main market (e2b). The answer category ‘more than I can count’ was assigned to the polypoly.

A distinction needs to be made between market structures and competition. Market structures mainly refer to the number of firms and perhaps their size distribution, while this may differ from competitive firm behaviour at the industry level (Martin 2012).

See http://ec.europa.eu/enlargement/index_en.htm. Accessed on 22 June 2016.

Collapsing the micro-data at the country-year level allows for a fixed effect at the macro-economic level. These unreported results confirm the conjecture that EU-membership is associated with less concentrated markets.

References

Acemoglu D, Aghion P, Zilibotti F (2006) Distance to frontier, selection, and economic growth. J Eur Econ Assoc 4(1):37–74

Aghion P, Bloom N, Blundell R, Griffith R, Howitt P (2005) Competition and innovation: an inverted-U relationship. Q J Econ 120:701–728

Angrist J, Chernozhukov V, Fernández-Val I (2006) Quantile regression under misspecification, with an application to the U.S. wage structure. Econometrica 74:539–563

Arrow K (1962) Economic welfare and the allocation of resources for invention. In: Nelson R (ed) The rate and direction of inventive activity. Princeton University Press, Princeton, pp 609–626

Bartelsman EJ, Haltiwanger J, Scarpetta S (2004) Microeconomic evidence of creative destruction in industrial and developing countries (policy research working paper no. 3463). World Bank, Washington

Boeheim M, Friesenbichler KS (2016) Exporting the competition policy regime of the European Union: success or failure? Empirical evidence for acceding countries. J Common Mark Stud 54(3):569–582

Buccirossi P, Ciari L, Duso T, Spagnolo G, Vitale C (2011) Measuring the deterrence properties of competition policy: the competition policy indexes. J Compet Law Econ 7(1):165–204

Clarke GRG (2011) Competition policy and innovation in accession countries: empirical evidence. Int J Econ Finance 3(3):1–10. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijef.v3n3p38

Correa PG, Fernandes AM, Uregian CJ (2010) Technology adoption and the investment climate: firm-level evidence for Eastern Europe and Central Asia. World Bank Econ Rev 24(1):121–147

de Bondt R, Vandekerckhove J (2012) Reflections on the relation between competition and innovation. J Ind Compet Trade 12:7–19

Demirgüç-Kunt A, Levine R (1999) Bank-based and market-based financial systems: cross-country comparisons. The World Bank Policy Research Papers. https://doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-2143

Devereux P (2007) Small sample bias in synthetic cohort models of labor supply. J Appl Econom 22:839–848

Dimitrova Q (2010) The new member states of the EU in the aftermath of enlargement: do new European rules remain empty shells? Eur J Public Policy 17(1):137–148

Djankov S, Murrell P (2002) Enterprise restructuring in transition: a quantitative survey. J Econ Lit 15:739–792

Dunne T, Klimek SD, Roberts MJ, Xu DY (2013) Entry, exit and the determinants of market structure. Rand J Econ 44(3):462–487

Dutz MA, Vagliasindi M (2000) Competition policy implementation in transition economies: an empirical assessment. Eur Econ review 44(4–6):762–772

Estrin S (2002) Competition and corporate governance in transition. J Econ Perspect 16(1):101–124

European Bank for Reconstruction and Development—EBRD (2013) Stuck in transition? Transition report 2013. European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, London

Ferrier GD, Klinedinst M, Linvill CB (1998) Static and dynamic productivity among Yugoslav enterprises: components and correlates. J Comp Econ 26:805–821

Friesenbichler K, Peneder M (2016) Innovation, competition and productivity. Econ Transit 24(3):535–580

Grabbe H (2002) European union conditionality and the “Cquis Communautaire”. Int Polit Sci Rev 23(3):249–268

Greene WH (2003) Econometric analysis, 5th edn. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs

Haskel JE, Pereira SC, Slaughter MJ (2007) Does inward foreign direct investment boost the productivity of domestic firms? Rev Econ Stat 89(3):482–496

Havrylyshyn O (2013) Is the transition over? A definition and some measurements. In: Hare P, Turley G (eds) Handbook of the economics and political economy of transition. Routledge, Abingdon, pp 59–73

Hayek FA (1968) Der Wettbewerb als Entdeckungsverfahren. Freiburger Studien, Tübingen

Helpman E, Melitz M, Rubinstein Y (2004) Export versus FDI with heterogeneous firms. Am Econ Rev 94:300–316

Hoelscher J, Stephan J (2009) Competition and antitrust policy in the enlarged European Union: a level playing field? J Common Mark Stud 47(4):863–889

Hsieh CT, Klenow PJ (2009) Misallocation and manufacturing TFP in China and India. Q J Econ 124(4):1403–1448

Kancs D (2007) Does economic integration affect the structure of industries? Empirical evidence from CEE. Econ Syst Res 19(1):73–97

Kornai J (1992) The postsocialist transition and the state: reflections in the light of Hungarian fiscal problems. Am Econ Rev 82(2):1–21

Krieger-Boden C, Soltwedel R (2013) Identifying European economic integration and globalization: a review of concepts and measures. Reg Stud 47(9):1425–1442

Machado JAF, Santos Silva JMC (2000) Glejser’s test revisited. J Econom 97(1):189–202

Martin S (2012) Market structure and market performance. Rev Ind Organ 40:87–108

Melitz MJ (2003) The impact of trade on intra-industry reallocations and aggregate industry productivity. Econometrica 71(6):1695–1725

Melitz MJ, Ottaviano GIP (2008) Market size, trade, and productivity. Rev Econ Stud 75(1):295–316

Méon PG, Weill L (2005) Does better governance foster efficiency? An aggregate frontier analysis. Econ Gov 6(1):75–90

Motta M (2004) Competition policy: theory and practice. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Münich D, Svejnar J (2007) Unemployment in East and West Europe. Labour Econ 14(4):681–694

Nickell SJ (1996) Competition and corporate performance. J Polit Econ 104(4):724–746

Olley GS, Pakes A (1992) The dynamics of productivity in the telecommunications equipment industry. No. w3977. National Bureau of Economic Research

Ospina S, Schiffbauer M (2010) Competition and firm productivity: evidence from firm-level data (IMF working paper no. 10/67). International Monetary Fund, Washington

Resmini L (2007) Regional patterns of industry location in transition countries: does economic integration with the European Union matter? Reg Stud 41(6):747–764

Saliola F, Seker M (2011) Total factor productivity across the developing world (enterprise surveys—enterprise note series working paper no. 23). The World Bank, Washington

Schimmelfenning F, Sedelmaier U (2004) Governance by conditionality: EU rule transfer to the candidate countries of Central and Eastern Europe. J Eur Public Policy 11(4):669–687

Schumpeter J (1942) Capitalism, socialism, and democracy. Harper and Bros, New York

Smeets R, Wei Y (2010) Productivity effects of United States multinational enterprises: the roles of market orientation and regional integration. Reg Stud 44(8):949–963

Sutton J (1991) Sunk costs and market structure. MIT Press, London

Syverson C (2011) What determines productivity? J Econ Lit 49:326–365

Verardi V, Croux C (2009) Robust regression in Stata. Stata J 9(3):439–453

Voigt S (2009) The effects of competition policy on development—cross-country evidence using four new indicators. J Dev Stud 45(8):1225–1248

Acknowledgements

For valuable comments and suggestions I would like to thank Karl Aiginger, George Clarke, Geoffrey Hewings, Peter Huber, Nils Karlsson, Bruce Lyons, Michael Pfaffermayr, Michael Peneder, Philipp Schmidt-Dengler and Patrik Tingvall. Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the EARIE 2015, the workshop on “Sustainable Regional Growth and Cohesion” at WIFO in 2014 and the research seminar at Ratio in 2016. I thank Anna Strauss, Peter Reschenhofer and Elisabeth Neppl for their research assistance. Research support from the Anniversary Fund of the Oesterreichische Nationalbank (Project No. 15280) is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Disclaimer: An earlier version was published as ‘Friesenbichler, Klaus S. 2014. “EU Accession, Domestic Market Competition and Total Factor Productivity. Firm Level Evidence.” WIFO Working Papers, no. 492 (December).’

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix

Appendix

Control variables | |

Foreign ownership | This is a dummy variable that takes on the value one if at least one of the (co-)owners is a private foreign individual, company or organisation |

State ownership, majority | A dummy variable that takes on the value one, if at least one of the (co-)owners is the government or the state, and if the public stake exceeds 50% |

State ownership, minority | A dummy variable that takes on the value one, if at least one of the (co-)owners is the government or the state, but holds a stake less than 50% |

Size of locality | An dummy variable takes on the value of one if the establishment is located in the country’s capital or a locality of more than 250,000 inhabitants, and zero otherwise |

University | The fraction of the persons employed full time that holds a university degree |

Labour | The labour stock is defined as the absolute number of persons employed full time |

Capital–labour-ratio | The capital–labour-ratio is computed as the capital stock divided by labour stock. The capital stock is defined as the replacement value of machinery, vehicles, equipment, land and buildings. This variable is a measure for the capital intensity |

Export share | This is the percentage of total sales that were exported, either directly or indirectly (sold domestically to a third party that exports products) |

Firm age | The firm age is the difference between the survey year and the year in which the establishment began operations |

Industry affiliation | Firms are assigned to 15 manufacturing and 9 service industries at the ISIC Rev. 3.1 two-digit level |

Import competition | Using BACI data, a trade database at the product level, we define import penetration ratio at the country level as a measure of economy-wide openness. The industry share of imports is used as an indicator for the relative import competition |

EBRD, C.P. | The EBRD transition indicator for competition policy |

Time and country effects | Dummy variables control for the survey waves and country-wide effects |

Country-level control variables | Additional country level variables used are the population density, the area of the country and GDP per capita (base year 2005) as well as GDP growth. The data were drawn from the World-Bank Development Indicator Database. See http://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/world-development-indicators [accessed on 1 Nov. 2016] |

Variables used in the productivity analysis | |

Sales | The establishment’s total annual sales |

Labour | The labour stock is defined as the absolute number of persons employed full time |

Capital stock | The capital stock is defined as the replacement value of machinery, vehicles, equipment, land and buildings |

Intermediate inputs | The cost of raw materials and intermediate goods used in production in the last fiscal |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Friesenbichler, K.S. Does EU-accession affect domestic market structures and firm level productivity?. Empirica 47, 343–364 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-018-9423-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-018-9423-9