Abstract

This study examines the long-run causal relationship between government revenues and spending of the Swedish economy over the period 1722–2011. The results based on hidden cointegration technique and a modified version of the Granger non-causality test, show that there exists a long-run and asymmetric relationship between government spending and government revenues. Our estimation results can be summarized into three main empirical findings. First, the government follows a hard budget constraint and soft budget constraint strategies in the case of negative and positive shocks, respectively. Second, negative shocks to the fiscal budget are removed fairly quickly compared to positive shocks. Third, bi-directional causality between revenues and expenditures offers support in favor of the fiscal synchronization hypothesis. The policy implication is that budget deficit’s reduction could be achieved through government spending cut, accompanied by contemporaneous tax controls.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Government budget has significant effects on many economic decisions, such as labor supply, savings and investments. The identification of the revenue-expenditure nexus is important to determine the appropriate strategy for fiscal discipline and fiscal policy. The aim of this paper is to examine the long-run causal relationship between government revenues and spending in Sweden during 1722–2011.

The major source of government revenue in Sweden was based on taxation. During the nineteenth century, Sweden had a state income tax system based on so-called appropriations. The system was rather heterogeneous, depending on the economic and social order present in the agricultural society.Footnote 1 In addition to these income taxes, there were also some basic taxes, such as armament fees and personal protection fees, which could be characterized as lump-sum taxes. These taxes were mainly ruled out during the 1890s and a completely new state income tax system, considered to be the predecessor of today’s ‘modern’ tax system, came into the picture in 1903.

By implementing the new tax system, it became mandatory for taxpayers to provide an income tax return which was rather progressive. Major state tax reforms were then carried out in different periods. Initially, the tax system had a pure fiscal function, i.e. taxes were imposed to finance public expenditures. During the 1930s, the function of the tax system also was to reduce cyclical fluctuations and stabilize the economy by under- or over-financing the budget. At the end of the 1940s, a more extensive function of redistribution was introduced as an important aspect of the tax system.

Beside the ordinary state tax system, temporary taxes were collected during and between the World Wars. The 1920 state tax system was more progressive than the 1903 and 1911 state tax systems. With the 1939 tax reform, the state marginal income tax rate starts to vary substantially between different income groups. The 1948 tax reform was almost exclusively supported from a redistribution perspective, which was highly controversial at that time. Although no new major state tax reform occurred until 1971, the state tax rate increased significantly for wage earners after the Second World War. The tax reform of 1971 was resulted in the fact that the deduction of the local tax paid was eliminated and the statutory tax rate decreased. However, this implied that the marginal income tax rate could be substantially higher, but also lower for taxpayers with low income. For income- re-distributional purposes, marginal income tax rates and progressivity was further emphasized in this reform. With minor tax reforms occurred in 1983–1985, and in particular, a major tax reform in 1990–1991, the tax rates decreased. Due to the crises and the depression of the 1990s, the tax rate was rather increased.

The government budget generally reflects the economic policy of a government, and it is partly through the budget that the government conducts its three main methods of establishing control: the allocative function, the stabilization function, and the distributive function. Over time, it was considerable changes in emphasis on these different economic functions of the budget. In the nineteenth century, government finance was primarily concerned with the allocative function. The goal of government was to raise revenue as efficiently as possible to perform the limited tasks, especially in case of infrastructure development. As the twentieth century began, the distribution function received increased significance. Social welfare benefits became important. In the later interwar period, and more especially in the 1950s and 1960s, stabilization was central, although equity was also a major concern in the design of tax systems. In the 1980s and 1990s, once more, allocative issues came into the picture, and stabilization and distribution became less significant in government finance.

With this historical background, it is interesting to examine the revenue-expenditure nexus accounting for possible asymmetric fluctuations of revenues over expenditures and vice versa. Especially, as the literature review section indicates, empirical evidence is mixed and inconclusive. Thus, the recently developed multivariate hidden cointegration (Granger and Yoon 2002) is applied as an alternative methodology to examine the long-run relationship between government spending and revenues.

The technique allows for asymmetry in the long-run relationship between data components and allows for distinct cointegrating relationships between subcomponents of time-series even when cointegration between two time-series is not identified. Another advantage of using this technique is that it allows a straightforward delimitation of the data in an economically sensible way. The process is estimated by the Johansen cointegration approach. To the best of my knowledge, this is the first study on the relationship between government spending and revenues based on Swedish historical data (1722–2011) using hidden cointegration and the Toda and Yamamoto (1995) and Yamada and Toda (1998) procedure which is expected to improve the standard F-statistics in the causality test procedure.

The paper is organized as follows: Sect. 2 reviews previous studies, Sect. 3 outlines some theoretical considerations, and Sect. 4 explains data and methodology used in this study. The results are presented and interpreted in Sect. 5. Finally, conclusions and policy implications are given in Sect. 6.

2 Previous studies

The literature on public spending and revenues can be categorized into four groups. First, the tax-and-spend hypothesis, proposed by Friedman (1978), suggests that increases in state taxes will result in increases in expenditures such that budget deficit reduction becomes unlikely. This hypothesis is confirmed by the existence of unidirectional causality running from revenues (i.e. taxes) to expenditures. This implies that imposition of higher taxes in order to reduce the size of the budget deficit would rather raise it instead.

Buchanan and Wagner (1978) indicate that increasing tax revenues reduces government expenditures via fiscal illusion; that is, the public perceives the use of indirect (rather than direct) taxation to finance government spending as being cheaper, even though they are paying for this spending through inflation, crowding out of the private sector and higher interest rates. This hypothesis supports a negative unidirectional causality running from revenues to expenditures. The fiscal illusion hypothesis, which is based on the public’s subjective perceptions of the cost of government spending, seems closer to asymmetric responses of revenue effects in expenditure relations. Bohn (1991), Mounts and Sowell (1997), Garcia and Henin (1999), Chang et al. (2002) and Payne et al. (2008) have provided evidence for the tax-and-spend hypothesis.

Second, the spend-and-tax hypothesis, suggested by Peacock and Wiseman (1979), claims that spending decisions are made first and then followed by the adjustment in tax revenues. This hypothesis is consistent with Barro (1979) view that expenditures are financed by higher future taxes and the budget deficit can only be reduced through spending cuts. However, the spend-and-tax hypothesis results in the existence of a positive unidirectional causality running from government expenditures to revenues. Evidence in favor of the spend-and-tax hypothesis has been provided by Von Fustenberg et al. (1986), Joulfaian and Mookerjee (1991), Provopoulos and Zambaras (1991), Koren and Stiassny (1995), Kollias and Makrydakis (2000), Hondroyiannis and Papapetrou (1996), Vamvoukas (1997), Ross and Payne (1998), Park (1998), Saunoris and Payne (2010), Afonso and Rault (2009), and Paleologou (2013).

Third, the fiscal synchronization hypothesis asserts that revenues and expenditures are adjusted simultaneously (Musgrave 1966; Meltzer and Richard 1981). According to this hypothesis, government’s decision on the optimal levels of expenditure and taxation is determined concurrently and depends on the voters’ welfare maximizing demand for public services and on voters’ attitude towards the redistribution function of the government, based on the comparison of their marginal benefits and cost of public services. This implies bidirectional causality between government expenditure and government revenue. In this case, governments make decisions about revenues and expenditures simultaneously. The studies of Miller and Russek (1989), Hasan and Sukar (1995), Li (2001), Kollias and Paleologou (2006), Paleologou (2013), and Athanasenas et al. (2014) have provided evidence for the fiscal synchronization hypothesis.

Fourth, the institutional separation or fiscal neutrality hypothesis states that decisions on revenues are independent from decisions on expenditures due to the independent functions of the executive and legislative branches of the government (Wildavsky 1988). Empirical evidence by Baghestani and McNown (1994), and Kollias and Paleologou (2006) reveal no relation between revenues and expenditures, supporting this hypothesis for a number of countries.

Thus, several studies have investigated the revenue-expenditure nexus and provided a mixed and contradictory evidence on the relationship between the variables. The results were dependent on the time period, the methodology used, and the countries in the sample. However, a few papers have estimated asymmetric relationship between government expenditures and revenues. Almost all these studies with some exceptions have used linear relationships in which the adjustment is assumed to be independent of whether shocks are positive or negative. However, if expenditures (revenues) respond faster and lager in magnitude to revenue (expenditures) increases than decreases then this relationship is asymmetric.

3 Theoretical framework

The literature on budget deficit sustainability is primarily concerned with whether or not the government’s intertemporal solvency constraint is violated. Hakkio and Rush (1991), Martin (2000), Cunado et al. (2004), and Paleologou (2013) have shown that cointegration between government revenues and expenditures is considered as evidence in support of the intertemporal budget constraint. The theoretical rationale underlying the use of the cointegration methodology starts with the government’s one-period budget constraint given in Eq. (1):

where SPEN t is government purchases of goods, services and transfer payments; B t is government debt; REVN t is government revenues, and i t is the real interest rate. Solving Eq. (1) leads to:

where r t = ∏s = 1 t Πσ s and σ s = (1 + i s ) − 1. The intertemporal budget solvency requires that the current debt must be financed by surpluses in future periods. This means that the second term on the right-hand side of Eq. (2) is: \(\mathop {\lim }\limits_{n \to \infty } r_{n} B_{n} = 0\). In the absence of this condition, the government is allowed to undertake a Ponzi scheme in which the maturing debt is financed by issuing a new debt. Sustainability of the budget deficit is related to the condition that the limit of the government debt term in Eq. (2) is equal to zero. Then, the stock of government debt is expected to grow on average no faster than the growth rate of the economy. Since the real interest rate is assumed to follow a stationary process (Hakkio and Rush 1991) this transforms Eq. (1) into a long-run relationship between government revenue and expenditure given as:

where SPEN t is government expenditures including interest payments on debt; α and β are the cointegrating parameters, and ε t shows the residuals reflecting the budgetary disequilibrium between REVN t and SPEN t . Thus, sustainability of a budget deficit requires that REVN t and SPEN t are cointegrated. There are two versions of sustainability. First, a deficit will exhibit “strong” sustainability if REVN t and SPEN t are cointegrated and β = 1. This means that the government follows a hard budget constraint strategy. If REVN t and SPEN t are cointegrated and 0 < β < 1, then, the deficit exhibits “weak” sustainability. This implies that the government follows a soft budget constraint strategy. However, the “weak” form of a sustainable budget deficit is not consistent with the government’s ability to market its debt in the long run. As the government expenditure increases more than it receives in revenues, the risk of default rises, i.e., the debt term may not converge to zero, leading to the government offering higher interest rates in order to service its debt.

4 Data and methodology

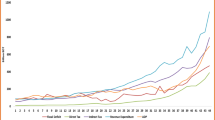

Data used in this study are government expenditures and revenues in Sweden over the period 1722–2011. The variables are in Swedish krona and obtained from Fregert and Svensson (2014). The descriptive statistics is shown in Table 1 and Fig. 1 indicates time plots of the variables. There is no any common approach as to the existence, or nature, of the asymmetric relationship between government spending and revenues. Error correction models (ECM) or vector autoregressive models (VAR) used in the literature suffer from problems of low power in test statistics and bias issues stemming from misspecified exogenous thresholds for determining statistical regimes. Furthermore, ECM or VAR models assume asymmetry as a short-run relationship between the series, i.e., asymmetry presents only in the adjustments process to the equilibrium and not in the cointegration relationship and there exists no long-run asymmetry.

To overcome the problems related to threshold autoregressive ECMs, Granger and Yoon (2002) approach is adopted here that deals effectively with these issues.Footnote 2 They investigate the presence of a co-integrating relationship not between the aggregate series but between their components, which they call ‘hidden co-integration’. That is, they allow for the possibility that, even if no linear co-integration exists, there may be a long-run relation between the positive and negative non-stationary components of some series.

This technique allows us to investigate not only if spending respond to revenue changes, but also if this response depends on the sign of the changes. Granger and Yoon also show that the non-linear adjustment mechanism to long-run equilibrium can be easily reduced to a linear one without any loss of information. Their hidden cointegration technique identifies the dynamics between data components.

The data components include both cumulative positive and negative changes of time series. If the components of two data series (negative or positive) are cointegrated, then the data has a hidden cointegration. This is an example of nonlinear cointegration that ordinary linear cointegration fails to identify. Suppose X t and Y t are two random walk time series:

where t = 1,2,…,T and X 0 , Y 0 are initial values, ε i and η i denote mean zero white noise disturbance terms. A standard cointegration exists if {X t ,Y t } are cointegrated by one cointegrating vector. When movements of X t and Y t are asymmetric, it is possible to detect hidden cointegrations between them. Granger and Yoon (2002) define positive and negative shocks as follows:

Thus,

Then the notations can be simplified with:

Thus,

Consequently,

The first difference (ΔX t = X t − X t−1) is calculated for both of the time series, which sort observations to positive and negative movements (ΔX + t and ΔX − t ). Then, it is also calculated the cumulative sum of positive (negative) changes, at a given time, for all variables (X + t = ∑ΔX + t and X − t = ∑ΔX − t ) via equations that are presented above. Similar calculations are implemented for Y. The variables X and Y are said to have hidden cointegration if their components are cointegrated. The process is estimated by implementing Johansen’s maximum likelihood approach.

Regarding the Granger non-causality test, Zapata and Rambaldi (1997) have shown that, in a regression context, for determining whether some parameters of the model are jointly zero, the traditional F-test is not valid when the variables are integrated or cointegrated and the test statistics does not have a standard distribution. This implies that the usual tests for exact linear restrictions on the parameters (e.g. the Wald test) do not have their usual asymptotic distributions if the data is integrated or cointegrated.

To deal with this issue and to avoid the pre-testing distortions associated with prior tests of non-stationarity and cointegration, the procedure proposed by Toda and Yamamoto (1995) and Yamada and Toda (1998) is used here to ensure that the usual test statistics for Granger causality have standard asymptotic distributions. They utilize a modified Wald test (MWald) for restrictions on the parameters of a VAR (k), where k is the lag length in the system. This test has an asymptotic Chi square distribution when a VAR (k + dmax) is estimated (where dmax is the maximal order of integration suspected to occur in the system).

Following Toda and Yamamoto (1995) and Yamada and Toda (1998), we can set up the following VAR(k + d(max)) model:

where B 0 is a 2 × 1 intercept vector, \(B_{1} - B_{{d_{\hbox{max} } }}\) are 2 × 2 matrices of coefficients and vec(ɛ) is white noise. Testing for Granger non-causality the general null hypothesis is,

where R is a (N × (22 · k + 2)) matrix of rank N and r is a (N × 1) null vector. N is the number of restrictions of the estimated coefficients and β = vec(B 0, …, B k ). Testing the hypothesis of Granger non-causality from REVN to SPEN (2) may be expressed in terms of the coefficients as,

where b 12 i are the coefficients of REVN t−1 and REVN t−k in the second equation of model (11). Evidence of causality from REVN to real SPEN is established by rejecting the null hypothesis. In a similar way, non-causality can be tested for the other direction. Evidence of causality from economic growth to REVN is established by rejecting the following null hypothesis, expressed in terms of the coefficients,

where b 21 i are the coefficients of SPEN t−1 and SPEN t−k in the first equation of model (11). This procedure is carried out both for positive and negative components.

Rambaldi and Doran (1996) have shown that MWald methods for testing Granger non-causality can be computed by using a seemingly unrelated regression (SUR). The main advantage of this method is that it does not require information regarding the cointegration properties of the system, as argued by Zapata and Rambaldi (1997).

A SUR-type VAR model has a normal, standard limiting Chi square distribution and the usual lag selection procedure to the system can be used even if there is no cointegration or if the stability and rank conditions are not fulfilled so long as the order of integration of the process is not greater than true lag length of the model (Yamada and Toda 1998). Furthermore, VAR models can be estimated using data in levels and testing for general restrictions even if the process may present integration or cointegration of an arbitrary order (Toda and Yamamoto 1995). We also perform a series of diagnostic tests to check whether the underlying statistical assumptions are fulfilled.

5 Estimation results

Positive and negative values for government expenditures and revenues, as described by Eqs. (4)–(10), are generated. First, we need to determine the degree of integration of each variable. A common practice is the use of the augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) test. We will use the Pantula principle where we start with the null hypothesis that the variable is I(2), and then reduce the order of differencing each time the null hypothesis is rejected until the null is not rejected. Schwarz’s criterion and the Breusch–Godfrey Lagrange multiplier test for residual autocorrelation of order p are used to choose the appropriate lag length. The second step is to test for hidden cointegration using the Johansen procedure. Tables 2 and 3 report the results of the ADF test for a second unit root and for one unit root. Comparing the ADF test statistics with their corresponding critical values, we conclude that the hypothesis of I(2) is rejected for all the series. Government expenditures and revenues are integrated of order one, I(1).

The hidden cointegration test results are obtained by implementing the Johansen maximum likelihood approach. The results, presented in Table 4, indicate that there is cointegration between both positive and negative components in the sample.Footnote 3 All the estimated cointegrating parameters are statistically significant at the conventional levels. The estimated vectors are normalized around government spending and these are shown in Table 5. The adjustment parameters are also estimated and presented in the last column of Table 5. The adjustment parameters also are statistically significant. However, the cointegration coefficient is close to unity in the case of negative values. The slope coefficient close to unity is an indication that the government follows a hard budget constraint strategy. The slope coefficient less than unity in the case of positive values means that the government follows a soft budget constraint strategy. Generally, these results imply that, over the long-run, the fiscal budget is strongly and weakly sustainable with fiscal taxes collections being able to cover 97 and 81% of the corresponding expenditure items, respectively. The adjustment parameters indicate that the government expenditures adjust to the deviation from the long-run equilibrium in the case of both positive and negative changes but there is quicker equilibrium reversion following a negative shock to governments budget whereas equilibrium adjustment is slower following a positive shock to the budget. In other words, the speed of adjustment when the budget is worsening is faster than when the budget is improving.

The results of the Granger non-causality tests, presented in Table 6, show that there is a bidirectional causality between negative and positive components of government spending and revenues. Moreover, the negative changes of revenues have a larger impact on the expenditures compared to the positive ones. A series of diagnostic tests is used to show that the underlying assumptions are fulfilled. Both models are successful in dealing with the problem of autocorrelation and normality as indicated by Tables 7, 8.

6 Conclusions and policy implications

This paper adopts the hidden cointegration approach (Granger and Yoon 2002) and the Granger non-causality methodology of the Toda and Yamamoto (1995) and Yamada and Toda (1998) to examine the response of Swedish government spending to Swedish government revenues’ changes and vice versa, during the period 1722–2011. The findings support clearly asymmetric fiscal adjustments, that is, government revenues (expenditures) react differently to increases and decreases of expenditures (revenues) in the long run. Furthermore, the negative changes of revenues have a larger impact on the expenditures compared to the positive ones. The government follows a hard budget constraint (strong deficit sustainability) and a soft budget constraint (weak deficit sustainability) strategies in the case of negative and positive values, respectively. Our estimation results further reveal that negative disturbances to the fiscal budget are corrected at a quicker rate than positive ones. Overall, our results offer support for the fiscal synchronization hypothesis.

The fiscal synchronization hypothesis or bidirectional causality between government expenditure and revenue argues that governments may change expenditure and taxes concurrently. This implies that, under the fiscal synchronization hypothesis, citizens decide on the level of spending and taxes. This is done through comparing the benefits of government to citizen’s marginal cost. Barro’s (1979) tax smoothing model provided further credence to the fiscal synchronization hypothesis. His model was based on the Ricardian equivalence view that deficit-financed government expenditure today results in future tax increases.

The existence of asymmetries in the budgetary adjustment process stems from different reasons: (1) policy makers respond differently to budget surplus as oppose to budget deficits since they would presumably be more aggressive in responding to deficits, (2) a close connection between the budget and business cycles due to the presence of automatic stabilizers and the observation that business cycles indicate asymmetric behavior, such asymmetries should translate to the budgetary adjustment process, (3) the belief that tax payers’ response to changes in the effective tax rate or tax base may also be asymmetric, (4) asymmetric variations in the interest rates and exchange rates in the international economy can translate into differences in trade tax revenues and profit tax revenues are sensitive to internal and external demand shocks, and (5) differences in defense expenditures are sensitive to political developments particularly during periods of war and peacetime (Ewing et al. 2006).

However, there are a number of policy implications of the findings. First, budget deficit’s reduction could be achieved through government expenditures cut, accompanied by contemporaneous tax controls. This outcome suggests that fiscal policymakers in Sweden should set revenues and expenditures simultaneously. That is, fiscal policymakers in Sweden should not make spending decisions in isolation from tax decisions. The joint determination of revenues and expenditures is appealing as long as it effectively restrains the budget deficit. Second, we further advise tax authorities to work closely with other fiscal institutions in moving towards a common goal of fiscal sustainability.

Notes

Stenkula et al. (2014) provide useful information about tax system in Sweden.

Another approach to investigate the possibility of asymmetric adjustment is threshold cointegration tests (e.g., Balke and Fomby 1997; Enders and Siklos 2001). In the threshold-autoregressive (TAR) model, asymmetry is a combination of short-run and long-run processes. The hidden cointegration is more flexible than threshold cointegration or the standard ECMs since it is not limited to two regimes and it is possible to explore all different combinations of cointegration between data components.

If cointegration was rejected, suggesting no long-run co-movements between government expenditures and revenues in the period 1722–2011, it could be possible to analyze short run co-movements among these variables and test for the Granger non-causality by dividing the sample into subperiods. Since cointegration is found in the whole sample, subperiod estimations are not performed.

References

Afonso A, Rault C (2009) Spend-and-tax: a panel data investigation for the EU. Econ Bull 29:2542–2548

Athanasenas A, Katrakilidis C, Trachanas E (2014) Government spending and revenues in the Greek economy: evidence from nonlinear cointegration. Empirica 41:365–376

Baghestani H, McNown R (1994) Do revenues or expenditure respond to budgetary disequilibria? South Econ J 60:311–322

Balke N, Fomby T (1997) Threshold cointegration. Int Econ Rev 38:627–645

Barro RJ (1979) On the determination of the public debt. J Polit Econ 87:940–971

Bohn H (1991) Budget balance through revenue or spending adjustments. J Monet Econ 27:333–359

Buchanan JM, Wagner RE (1978) Dialogues concerning fiscal religion. J Monet Econ 4:627–636

Chang T, Liu WR, Caudill SB (2002) Tax-and-spend, spend-and-tax, or fiscal synchronization: new evidence for ten countries. Appl Econ 34:1553–1561

Cunado J, Gil-Alana LA, Gracia FP (2004) Is the US fiscal deficit sustainable? A fractionally integrated approach. J Econ Bus 56:501–526

Enders W, Siklos PL (2001) Cointegration and threshold adjustment. J Bus Econ Stat 19(2):166–176

Ewing BT, Payne JE, Thompson MA, Al-Zoubi OM (2006) Government expenditures and revenues: evidence from asymmetric modeling. South Econ J 73:190–200

Fregert K, Svensson, R. (2014). Fiscal statistics for Sweden, 1670–2011. In: Edvinsson R, Jacobson T, Waldenström D (eds) Historical monetary and financial statistics for Sweden, vol II. House prices, stock returns, national accounts, and the riksbank balance sheet, 1620–2012, Ekerlid, Swedish Central Bank, Stockholm

Friedman M (1978) The limitations of tax limitation. Policy Rev, Summer, pp 7–14

Garcia S, Henin P-Y (1999) Balancing budget through tax increases or expenditure cuts: is it neutral? Econ Model 16:591–612

Granger CW, Yoon G (2002) Hidden cointegration. Department of Economics Working Paper. University of California, San Diego

Hakkio CS, Rush M (1991) Is the budget deficit “too large”? Econ Inq 29:429–445

Hasan SY, Sukar AH (1995) Short and long-run dynamics of expenditures and revenues and the government budget constraint: further evidence. J Econ 22:35–42

Hondroyiannis G, Papapetrou E (1996) An examination of the causal relationship between government spending and revenue: a cointegration analysis. Public Choice 89:363–374

Joulfaian D, Mookerjee R (1991) Dynamics of government revenues and expenditures in industrial economies. Appl Econ 23:1839–1844

Kollias C, Makrydakis S (2000) Tax and spend or spend and tax? Empirical evidence from Greece, Spain, Portugal and Ireland. Appl Econ 32:533–546

Kollias C, Paleologou S-M (2006) Fiscal policy in the European Union: tax and spend, spend and tax, fiscal synchronization or institutional separation? J Econ Stud 33:108–120

Koren S, Stiassny A (1995) Tax and spend or spend and tax? An empirical investigation for Austria. Empirica 22:127–149

Li X (2001) Government revenue, government expenditure, and temporal causality: evidence from China. Appl Econ 33:485–497

Martin GM (2000) US deficit sustainability: a new approach based on multiple endogenous breaks. J Appl Econom 15:83–105

Meltzer AH, Richard SF (1981) A rational theory of the size of government. J Polit Econ 89:914–927

Miller SM, Russek FS (1989) Co-integration and error-correction models: the temporal causality between government taxes and spending. South Econ J 57:221–229

Mounts SW, Sowell C (1997) Taxing, spending and the budget process: the role of the budget regime in the intertemporal budget constraint. Swiss J Econ Stat 133:421–439

Musgrave R (1966) Principles of budget determination. In: Cameron H, Henderson W (eds) Public finance: selected readings. Random House, New York, pp 15–27

Paleologou S-M (2013) Asymmetries in the revenue-expenditure nexus: a tale of three countries. Econ Model 30:52–60

Park WK (1998) Granger causality between government revenues and expenditures in Korea. J Econ Dev 23:145–155

Payne JE, Mohammadi H, Cak M (2008) Turkish budget deficit sustainability and the revenue expenditure nexus. Appl Econ 40:823–830

Peacock AT, Wiseman J (1979) Approaches to the analysis of government expenditure growth. Public Financ Q 7:3–23

Provopoulos G, Zambaras A (1991) Testing for causality between government spending and taxation. Public Choice 68:277–282

Rambaldi AN, Doran HE (1996) Testing for Granger non-causality in cointegrated systems made easy. Working Papers in Econometrics and Applied Statistics, Department of Econometrics, University of New England, vol. 88, pp 1–22

Ross KL, Payne JE (1998) A reexamination of budgetary disequilibria. Public Financ Rev 26:67–79

Saunoris JW, Payne JE (2010) Tax more or spend less? Asymmetries in the UK revenue–expenditure nexus. J Policy Model 32:478–487

Stenkula M, Johansson DDu, Rietz G (2014) Marginal taxation on labour income in Sweden from 1862 to 2010. Scand Econ Hist Rev 62(2):163–187

Toda YH, Yamamoto T (1995) Statistical inference in vector autoregressions with possibly integrated processes. J Econ 66:225–250

Vamvoukas G (1997) Budget expenditures and revenues: an application of error-correction modelling. Public Financ Rev 52:125–138

Von Fustenberg G, Green R, Jeong J (1986) Tax and spend, or spend and tax? Rev Econ Stat 68:179–188

Wildavsky A (1988) The new politics of the budgetary process. Scott Foresman, Glenview

Yamada H, Toda YH (1998) Inference in possibly integrated vector autoregressive models: some finite evidence. J Econ 86:55–95

Zapata HO, Rambaldi AN (1997) Monte Carlo evidence on cointegration and causation. Oxford Bulletin Econ Statistics 59(2):285–298

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the editor and two anonymous referees for their valuable comments and suggestions. Remaining errors are my responsibility.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Irandoust, M. Government spending and revenues in Sweden 1722–2011: evidence from hidden cointegration. Empirica 45, 543–557 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-017-9375-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-017-9375-5