Abstract

Central to this paper is the analysis of inflation dynamics in the Euro Area as well as in eleven individual Euro Area member countries between 1990 and 2012. Based on the hybrid new Keynesian Phillips curve, the analyses include survey measures from Consensus Economics to compare inflation dynamics across Euro Area member countries. Particular focus is set on the choice of suitable measures of real marginal cost. In addition to the well-known output gap, the role of finance-neutral output gaps and unemployment gaps is examined. Throughout the analyses, price setting is found to be largely backward-looking, but with a decreasing trend over time. Countries’ varying sensitivity to the different measures of real marginal cost is highlighted, which may indicate persistent heterogeneity in Euro Area inflation dynamics. With the onset of the financial crisis, finance-neutral output gaps outperform alternative measures of real marginal cost.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

EA data is calculated as the weighted average of EA11 countries based on quarterly Gross Domestic Product (GDP) weights; in the case of GDP and credit data, sums of absolute values are included.

Forecast errors are determined as mean absolute percentage errors (MAPE) and found to be smaller than 20 basis points in the majority of countries. Thus, forecasts are considered overall unbiased. The fact that forecasters themselves (among them Consensus Economics forecasters) rely on Phillips curve relationships when forming expectations on macroeconomic variables (Fendel et al. 2011) is considered a further viable justification for using Consensus Economics inflation forecasts.

An exception to the broad literature supporting survey measures of inflation expectations has been Nunes (2010) who finds the weight of rational expectations to be comparably higher and concludes that survey expectations do not correspond to ‘true’ inflation expectations.

HAC weight matrix using Bartlett (Newey-West) kernel with a lag length of four is chosen here.

Following Borio et al. (2007), the trade-weighted output gap takes into account the share of EA10 related imports relative to total imports of one country in the respective quarter. The weight is calculated based on information of the IMF Direction of Trade Database.

Correlations between the output gap and the EA-weighted output gap are >0.99 in all EA-countries. A detailed description of trade weight derivations and estimation results are available upon request.

Testing for the inflationary pressure of real effective exchange rates in a similar set-up to that of oil prices does, nonetheless, not yield significant insights into the inflation formation process. Both results are available upon request.

Testing for weak instruments indicates that the hypothesis of weak instruments can be rejected only at the >10 % confidence interval for the following countries: Austria, Finland, France, and Ireland.

Estimation results are not reported separately, but are available upon request.

Despite technical disadvantages of the HP filter compared to other filtering methods, e.g. band-pass filters, it is preferred due to the possibility of estimating it in state space form.

In line with the traditional HP filter, \(\lambda \) is set to 1600, determined by the error variances of the respective state and observation equation. In order to ensure that implicit business cycle frequencies correspond to those of the standard HP filter in the baseline specification, \(\lambda \) is set in line with Borio et al. (2014). Particular attention is paid to \(\beta \), as values close to one would estimate unit root output gaps, but, with the exception of the EA aggregate, values never approach the upper limit of 0.95.

Various additional variables may be included to represent the financial cycle, among them measures of credit quality and spreads, financial firm indicators as well as leverage and liquidity. With respect to limited availability of data for EA11 countries, preference is given to the estimation of finance-neutral output gaps for all EA11 countries, accepting a smaller set of financial cycle variables.

Due to partially short time series for residential property prices, this time series has been excluded from the observation equation when the number of observations was reduced extensively. Table 3 indicates where this is the case.

As the post-2007 data sample is still rather small, analyses are expected to be more informative as longer time series become available.

Testing for a break in 1999 (2001 in the case of Greece) in response to the changeover to the Euro indicates a decrease in \(\gamma _b\) in the majority of countries. No systematic differences are, nonetheless, observed for the role of the output gap.

References

Adam K, Padula M (2011) Inflation dynamics and subjective expectations in the United States. Econ Inq 49(1):13–25

Batchelor R (2001) How useful are the forecasts of intergovernmental agencies? The IMF and OECD versus the consensus. Appl Econ 33(2):225–235

Beccarini A, Gros D (2008) At what cost price stability? New evidence about the Phillips curve in Europe and the United States. CEPS Working Document, No. 302

Benigno P, López-Salido JD (2006) Inflation persistence and optimal monetary policy in the Euro Area. J Money Credit Bank 38(3):587–614

Borio C (2014) The financial cycle and macroeconomics: What have we learnt? J BanK Finance 45:182–198

Borio C, Disyatat P, Juselius M (2014) A parsimonious approach to incorporating economic information in measures of potential output. BIS Working Papers, No. 442

Borio C, Disyatat P, Juselius M et al (2013) Rethinking potential output: embedding information about the financial cycle. BIS Working Papers, No. 404

Borio C, Filardo A J (2007) Globalisation and inflation: new cross-country evidence on the global determinants of domestic inflation. BIS Working Papers, No. 227

Brissimis SN, Magginas NS (2008) Inflation forecasts and the new Keynesian Phillips curve. Int J Cent Bank 4(2):1–22

Buchmann M (2009) Nonparametric hybrid Phillips curves based on subjective expectations: estimates for the Euro Area. ECB Working Paper Series, No. 1119

Calvo GA (1983) Staggered prices in a utility-maximizing framework. J Monet Econ 12(3):383–398

Christiano LJ, Eichenbaum M, Evans CL (2005) Nominal rigidities and the dynamic effects of a shock to monetary policy. J Polit Econ 113(1):1–45

Claessens S, Kose MA, Terrones ME (2012) How do business and financial cycles interact? J Int Econ 87(1):178–190

Dovern J, Fritsche U, Slacalek J (2012) Disagreement among forecasters in G7 countries. Rev Econ Stat 94(4):1081–1096

Dovern J, Weisser J (2011) Accuracy, unbiasedness and efficiency of professional macroeconomic forecasts: an empirical comparison for the G7. Int J Forecast 27(2):452–465

Dreher A, Marchesi S, Vreeland JR (2008) The political economy of IMF forecasts. Public Choice 137(1):145–171

Drehmann M, Borio C, Tsatsaronis K (2012) Characterising the financial cycle: don’t lose sight of the medium term! BIS Working Papers, No. 380

ECB (2015). The definition of price stability. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/mopo/strategy/pricestab/html/index.en.html. Accessed 14 July 2015

European Commission (2014) Analysing current disinflationary trends in the Euro Area. European Economy: European Economic Forecast, 2/2014

Fendel R, Lis EM, Rülke J-C (2011) Do professional forecasters believe in the Phillips curve? Evidence from the G7 countries. J Forecast 30(2):268–287

Frenkel M, Rülke J-C, Zimmermann L (2013) Do private sector forecasters chase after IMF or OECD forecasts? J Macroecon 37:217–229

Friedman M (1968) The role of monetary policy. Am Econ Rev 58:1–17

Fuhrer J, Olivei G, Tootell G M (2009) Empirical estimates of changing inflation dynamics. Federal Reserve Bank of Boston Working Papers, No. 09/4

Galí J, Gertler M, Lopez-Salido JD (2001) European inflation dynamics. Eur Econ Rev 45(7):1237–1270

Galí J, Gertler ML (1999) Inflation dynamics: a structural econometric analysis. J Monet Econ 44(2):195–222

Galí J, Gertler ML, David López-Salido J (2005) Robustness of the estimates of the hybrid New Keynesian Phillips curve. J Monet Econ 52(6):1107–1118

Henzel S, Wollmershaeuser T (2008) The new Keynesian Phillips curve and the role of expectations: evidence from the Ifo world economic survey. Econ Model 25(5):811–832

Hodrick RJ, Prescott EC (1997) Postwar US business cycles: an empirical investigation. J Money Credit Bank 29(1):1–16

IMF (2013) The dog that didn’t bark: has inflation been muzzled or was it just sleeping. IMF World Economic Outlook (April). Chapter 3:1–17

Jondeau E, Le Bihan H (2005) Testing for the new Keynesian Phillips curve. Additional international evidence. Econ Model 22(3):521–550

Kleibergen F, Mavroeidis S (2009) Weak instrument robust tests in GMM and the new Keynesian Phillips curve. J Bus Econ Stat 27(3):293–311

Koop G, Onorante L (2012) Estimating Phillips curves in turbulent times using the ECB’s Survey of Professional Forecasters. ECB Working Paper Series, No. 1422

Mavroeidis S (2005) Identification issues in forward-looking models estimated by GMM, with an application to the Phillips curve. J Money Credit Bank 37(3):421–448

Mavroeidis S, Plagborg-Møller M, Stock JH (2014) Empirical evidence on inflation expectations in the new Keynesian Phillips curve. J Econ Lit 52(1):124–188

Mazumder S (2010) The new Keynesian Phillips curve and the cyclicality of marginal cost. J Macroecon 32(3):747–765

McAdam P, Willman A (2004) Supply, factor shares and inflation persistence: re-examining Euro-area new-Keynesian Phillips curves. Oxf Bull Econ Stat 66(Supplement):637–670

Montiel Olea JL, Pflueger C (2013) A robust test for weak instruments. J Bus Econ Stat 31(3):358–369

Montoya LA, Doehring B (2011) The improbable renaissance of the Phillips curve: the crisis and Euro Area inflation dynamics. European Commission Economic Papers, No 446

Newey WK, West KD (1987) A simple, positive semi-definite, heteroskedasticity and autocorrelationconsistent covariance matrix. Econometrica 55(3):703–708

Nunes R (2010) Inflation dynamics: the role of expectations. J Money Credit Bank 42(6):1161–1172

Oinonen S, Paloviita M (2014) Updating the Euro Area Phillips curve: the slope has increased. Bank of Finland Research Discussion Papers, No. 31/2014

Oinonen S, Paloviita M, Vilmi L (2013) How have inflation dynamics changed over time? Evidence from the Euro Area and USA. Bank of Finland Research Discussion Papers, No. 6/2013

O’Reilly G, Whelan K (2005) Has Euro-area inflation persistence changed over time? Rev Econ Stat 87(4):709–720

Paloviita M (2006) Inflation dynamics in the Euro Area and the role of expectations. Empir Econ 31(4):847–860

Paloviita M (2008) Estimating open economy Phillips curves for the Euro Area with directly measured expectations. Bank of Finland Research Discussion Papers, No. 16/2008

Phelps ES (1967) Phillips curves, expectations of inflation and optimal unemployment over time. Economica 34:254–281

Phillips AW (1958) The relation between unemployment and the rate of change of money wage rates in the United Kingdom, 1862–1957. Economica 25:283–299

Riggi M, Venditti F (2014) Surprise! Euro Area inflation has fallen, Bank of Italy Occasional Paper, No 237

Roberts JM (1997) Is inflation sticky? J Monet Econ 39(2):173–196

Rotemberg JJ (1982) Sticky prices in the United States. J Polit Econ 90(6):1187–1211

Rudd J, Whelan K (2005a) Does labor’s share drive inflation? J Money Credit Bank 37(2):297–312

Rudd J, Whelan K (2005b) New tests of the new-Keynesian Phillips curve. J Monet Econ 52(6):1167–1181

Rudd J, Whelan K (2007) Modeling inflation dynamics: a critical review of recent research. J Money Credit Bank 39(Supplement S1):155–170

Rumler F (2007) Estimates of the open economy new Keynesian Phillips curve for Euro Area countries. Open Econ Rev 18(4):427–451

Staiger DO, Stock JH (1997) Instrumental variables regression with weak instruments. Econometrica 65(3):557–586

Stock J H, Yogo M (2005) Testing for weak instruments in linear IV regression. In: Andrews DW, Stock JH (eds) Identification and inference for econometric models: essays in honor of Thomas J. Rothenberg, 80–108

Woodford M (2003) Interest and prices: foundations of a theory of monetary policy. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Woodford M (2007) Interpreting inflation persistence: comments on the conference on ’quantitative evidence on price determination’. J Money Credit Bank 39(Supplement 1):203–210

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: Variables and data sources

Variable | Source | Comment |

|---|---|---|

Time span | ||

HICP: Inflation Year-over-year (yoy) change harmonized index of consumer prices (HICP) in % | Eurostat OECD | HICP inflation (Eurostat), beginning of 1990s complemented with CPI inflation (OECD) |

Q1 1990-Q4 2012 | ||

CHICP: Core inflation yoy change CHICP in % | Eurostat OECD | CHICP inflation (Eurostat), before 1997 complemented with core CPI inflation (OECD) |

Q1 1990-Q4 2012 | ||

IFC: Inflation expectations Survey measure of expected inflation for the current and coming year | Consensus Economics | Quarterly data based on monthly forecasts for current and coming year |

Q1 1990-Q4 2012 | ||

GAP: Output gap Deviation of GDP from HP filtered GDP in % of HP filtered GDP | Eurostat AMECO | Real GDP in mEUR seasonally adjusted and adj. by working days |

Q1 1979-Q4 2012 | ||

FNGAP: Finance-neutral output gap (1) log real credit to the private non-financial sector in bnEUR (2) log real residential property price index | OECD | Both time series are demeaned using Cesàro means |

Q1 1990-Q4 2012 | ||

UGAP: Unemployment gap Deviation of the harmonized unemployment rate from its structural level | OECD | Annual NAIRU estimates (OECD) for four quarters of the respective year |

Q1 1990-Q4 2012 | ||

OIL: Oil price Crude oil, Brent in EUR yoy growth in % | Thomson Reuters Ecowin | Quarterly oil price corresponds to three-month averages |

Q1 1990-Q4 2012 | ||

NULC: Nominal unit labour cost yoy change in NULC in % | Eurostat AMECO | Seasonally adjusted and adj. by working days (Eurostat), complemented with AMECO data |

Q1 1990-Q4 2012 | ||

RULC: Real unit labor cost yoy change in RULC in % | Eurostat AMECO | Seasonally adjusted and adj. by working days (Eurostat), complemented with AMECO data |

Q1 1990-Q4 2012 | ||

I3M: Short-term interest rate 3-month Euribor/3-month money market rates in % | Eurostat | 3-month money market rates before 1999 |

Q1 1990-Q4 2012 | ||

I10Y: Long-term interest rate 10-year government bond interest rates | Eurostat | EMU convergence criterion bond yields |

Q1 1990-Q4 2012 | ||

SPREAD: Interest rate spread Difference between long- and short-term interest rates | own calculations | – |

Q1 1990- Q4 2012 | ||

REERL/REERC: Real effective exchange rate Index (level values) or yoy growth in % | BIS | Index values or yoy growth included depending on correlation statistics |

Q1 1990-Q4 2012 | ||

CAPAL/CAPAC: Capacity utilization Share of total in % or yoy growth in % | European Commission | Business and Consumer Survey, question #13; index values or yoy growth included depending on correlation statistics |

Q1 1990-Q4 2012 |

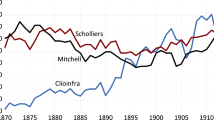

Appendix 2: Baseline specification rolling regression estimation results

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Amberger, J., Fendel, R. Understanding inflation dynamics in the Euro Area: deviants and commonalities across member countries. Empirica 44, 261–293 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-016-9322-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-016-9322-x