Abstract

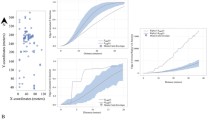

Citrus black spot (CBS), caused by Phyllosticta citricarpa, is one of the main fungal diseases of citrus worldwide. The Mediterranean Basin is free of the disease and thus phytosanitary measures are in place to avoid the entry of P. citricarpa in the EU territory. However, the suitability of the climates present in the Mediterranean Basin for CBS establishment and spread is debated. As a case study, an analysis of climate types and environmental variables in South Africa was conducted to identify potential associations with CBS distribution. The spread of the disease was traced and georeferenced datasets of CBS distribution and environmental variables were assembled. In 1950 CBS was still confined to areas of temperate climates with summer rainfall (Cw, Cf), but spread afterwards to neighbouring regions with markedly drier conditions. Actually, the hot arid steppe (BSh) is the predominant climate where CBS develops in South Africa nowadays. The disease was not detected in the Mediterranean-type climates Csa and Csb as defined by the Köppen-Geiger system and the more restrictive Aschmann’s classification criteria. However, arid steppe (BS) climates, where CBS is prevalent in South Africa, are common in important citrus areas in the Mediterranean Basin. The most noticeable change in the environmental range occupied by CBS in South Africa was the amount and seasonality of rainfall. Due to the spread of the disease to dryer regions, the minimum annual precipitation in CBS-affected areas declined from 663 mm in 1950 to 339 mm at present. The minimum value precipitation of warmest quarter also declined from 290 to 96 mm. Strong spatial autocorrelation in CBS distribution data was detected, so further modelling efforts should consider the relative contribution of environmental variables and spatial effects to estimate the potential geographical range of CBS.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Anonymous (1984). R.110 Agricultural pest act, 1983 (Act 36 of 1983). Control measures. Government Gazette, 9047, 6–11.

Anonymous (2000). Council Directive 2000/29/EC of 8 May 2000 on protective measures against the introduction into the Community of organisms harmful to plants or plant products and against their spread within the Community. Official Journal of the European Communities, L 169, 1–112.

Anonymous (2002). R.831 Agricultural pest act, 1983 (Act 36 of 1983). Control measures: Amendment. Government Gazette, 23517, 15–17.

Anonymous (2005a). R.457 Agricultural pest act, 1983 (Act 36 of 1983). Control measures: Amendment. Government Gazette, 27580, 3–4.

Anonymous (2005b). R.563 Correction notice. Agricultural pest act, 1983 (Act 36 of 1983). Control measures: amendment. Government Gazette, 27665, 5–6.

Anonymous (2006). Commission Decision of 5 July 2006 recognising certain third countries and certain areas of third countries as being free from Xanthomonas campestris (all strains pathogenic to Citrus), Cercospora angolensis Carv. et Mendes and Guignardia citricarpa Kiely (all strains pathogenic to Citrus). Official Journal of the European Union, L 187, 35–36.

Anonymous (2008). R.461 Agricultural pest act, 1983 (Act 36 of 1983). Control measures: amendment. Government Gazette, 30988, 4–5.

Anonymous (2014a). R.442 Agricultural pest act, 1983 (Act 36 of 1983). Control measures: amendment. Government Gazette, 37702, 4–11.

Anonymous (2014b). Title7: Agriculture. Part 319 Foreign quarantine notices. Subpart 56 Fruits and Vegetables. U.S. Government Printing Office. Code of Federal Regulations, 304–373.

APHIS, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service USA (2012). Pest-free areas. http://www.aphis.usda.gov/import_export/plants/manuals/ports/downloads/DesignatedPestFreeAreas.pdf. Accessed 5 Dec 2014.

Araújo, D., Raetano, C., Ramos, H., Spósito, M., & Prado, E. (2013). Interferência da redução no volume de aplicação sobre o controle da mancha preta (Guignardia citricarpa Kiely) em frutos de laranja ‘Valência’. Summa Phytopathologica, 39, 172–179.

Aschmann, H. (1973). Distribution and peculiarity of Mediterranean ecosystems. In F. Di Castri & H. A. Mooney (Eds.), Mediterranean type ecosystems. Origin and structure (pp. 11–19). New York: Springer.

Bivand, R. (2014). spdep: spatial dependence: weighting schemes, statistics and models. R package version 0.5-77. http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=spdep.

Bivand, R., Keitt, T., & Rowlingson, B. (2014). rgdal: bindings for the geospatial data abstraction library. R package version 0.8-16. http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rgdal.

Carstens, E., le Roux, H. F., Holtzhausen, M. A., van Rooyen, L., Coetzee, J., Wentzel, R., Laubscher, W., Dawood, Z., Venter, E., Schutte, G. C., Fourie, P. H., & Hattingh, V. (2012). Citrus black spot is absent in the Western Cape, Northern Cape and Free State Provinces. South African Journal of Science, 108, 56–61.

Chandelier, A., Helson, M., Dvorakb, M., & Gischer, F. (2014). Detection and quantification of airborne inoculum of Hymenoscyphus pseudoalbidus using real-time PCR assays. Plant Pathology, 63, 1296–1305.

DAFF, Department of Agriculture Forestry and Fisheries South Africa (2009). Movement of citrus plants and other citrus related plants. Citrus maps poster 2009. http://www.nda.agric.za/doaDev/sideMenu/plantHealth/docs/CitrusMapsPoster2009.pdf. Accessed 21 Oct 2014.

DAFF, Department of Agriculture Forestry and Fisheries South Africa (2014). The standards of plant quarantine on fresh orange grapefruit and lemon produced in the Republic of South Africa and on fresh orange and grapefruit produced in the Kingdom of Swaziland. http://www.nda.agric.za/doaDev/sideMenu/plantHealth/Japancitrusprotocol.htm. Accessed 5 Dec 2014.

Doidge, E. M. (1929). Some diseases of citrus prevalent in South Africa. South African Journal of Science, 26, 320–325.

EFSA, European Food Safety Authority. (2008). Scientific opinion of the panel on plant health (PLH) on a request from the European Commission on Guignardia citricarpa Kiely. The EFSA Journal, 925, 1–108.

EFSA, European Food Safety Authority. (2014). Scientific opinion on the risk of Phyllosticta citricarpa (Guignardia citricarpa) for the EU territory with identification and evaluation of risk reduction options. EFSA Journal, 12, 3557.

Er, H. L., Roberts, P. D., Marois, J. J., & van Bruggen, A. H. C. (2013). Potential distribution of citrus black spot in the United States based on climatic conditions. European Journal of Plant Pathology, 137, 635–647.

FAO, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2014). Crop production database FAOSTAT. http://faostat.fao.org/default.aspx. Accessed 12 Dec 2014.

Fourie, P. H., Schutte, G. C., Serfontein, S., & Swart, S. H. (2013). Modeling the effect of temperature and wetness on Guignardia pseudothecium maturation and ascospore release in citrus orchards. Phytopathology, 103, 281–292.

Gebrehiwet, Y., Ngqangweni, S., & Kirsten, J. F. (2007). Quantifying the trade effect of sanitary and phytosanitary regulations of OECD countries on South African food exports. Agrekon, 46, 23–39.

Graham, J. H., Gottwald, T. R., Timmer, L. W., Bergamin Filho, A., Van den Bosch, F., Irey, M. S., Taylor, E., Magarey, R. D., & Takeuchi, Y. (2014). Response to “Potential distribution of citrus black spot in the United States based on climatic conditions”, Er et al. 2013. European Journal of Plant Pathology, 139, 231–234.

Hijmans, R. J. (2014). Raster: geographic data analysis and modeling. R package version 2.2-31. http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=raster.

Hijmans, R. J., Cameron, S. E., Parra, J. L., Jones, P. G., & Jarvis, A. (2005). Very high resolution interpolated climate surfaces for global land areas. International Journal of Climatology, 25, 1965–1978.

IPPC, International Plant Protection Convention (1995). Requirements for the establishment of pest free areas. International Standards for Phytosanitary Measures, ISPM 4. Rome: IPPC.

IPPC, International Plant Protection Convention (2005). Requirements for the establishment of areas of low pest prevalence. International Standards for Phytosanitary Measures, ISPM 22. Rome: IPPC.

IPPC, International Plant Protection Convention (2007). Recognition of pest free areas and areas of low pest prevalence. International Standards for Phytosanitary Measures, ISPM 29. Rome: IPPC.

Kiely, T. B. (1948). Preliminary studies on Guignardia citricarpa, n. sp.: the ascigenous stage of Phoma citricarpa McAlp. and its relation to black spot of citrus. Proceedings of the Linnean Society of New South Wales, 68, 249–292.

Klausmeyer, K. R., & Shaw, M. R. (2009). Climate change, habitat loss, protected areas and the climate adaptation potential of species in Mediterranean ecosystems worldwide. Plos One, 4, e6392.

Köppen, W. (1936). Das geographisca system der klimate. In W. Köppen & G. Geiger (Eds.), Handbuch der klimatologie (p. 44). Berlin: Gebrüder Borntraeger.

Korf, H. J. G. (1998). Survival of Phyllostica citricarpa, anamorph of the citrus black spot pathogen. M. Sc. Thesis. Pretoria: University of Pretoria.

Kotzé, J. M. (1981). Epidemiology and control of citrus black spot in South-Africa. Plant Disease, 65, 945–950.

Kotzé, J. M. (2000). Black spot. In L. W. Timmer, S. M. Garnsey, & J. H. Graham (Eds.), Compendium of citrus diseases (2nd ed., pp. 10–12). St. Paul: APS Press.

Latimer, A. M., Wu, S. S., Gelfand, A. E., & Silander, J. A. (2006). Building statistical models to analyze species distributions. Ecological Applications, 16, 33–50.

Lee, Y. S., & Huang, C. S. (1973). Effect of climatic factors on the development and discharge of ascospores of the citrus black spot fungus. Journal of Taiwan Agricultural Research, 22, 154–144.

Loecher, M. (2014). RgoogleMaps: overlays on Google map tiles in R. R package version 1.2.0.6. http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=RgoogleMaps.

Magarey, R., Sutton, T., & Thayer, C. (2005). A simple generic infection model for foliar fungal plant pathogens. Phytopathology, 95, 92–100.

Magarey, R., Chanelli, S., & Holtz T. (2011). Validation study and risk assessment: Guignardia citricarpa, (citrus black spot). USDA-APHIS-PPQ-CPHST-PERAL /NCSU.

MAGRAMA, Ministerio de Agricultura, Alimentación y Medio Ambiente (2013). Anuario de estadística 2013. (pp. 1095). Madrid: MAGRAMA, Secretaría General Técnica, Centro de Publicaciones.

Makowski, D., Vicent, A., Pautasso, M., Stancanelli, G., & Rafoss, T. (2014). Comparison of statistical models in a meta-analysis of fungicide treatments for the control of citrus black spot caused by Phyllosticta citricarpa. European Journal of Plant Pathology, 139, 79–94.

McOnie, K. C. (1964a). Apparent absence of Guignardia citricarpa Kiley from localities where citrus black spot is absent. South African Journal of Agricultural Science, 7, 347–354.

McOnie, K. C. (1964b). The latent occurrence in citrus and other hosts of Guignardia easily confused with G. citricarpa, the citrus black spot pathogen. Phytopathology, 54, 40–43.

McOnie, K. C. (1964c). Orchard development and discharge of ascospores of Guignardia citricarpa and onset of infection in relation to control of citrus black spot. Phytopathology, 54, 1448–1454.

Mondal, S. N., Gottwald, T. R., & Timmer, L. W. (2003). Environmental factors affecting the release and dispersal of ascospores of Mycosphaerella citri. Phytopathology, 93, 1031–1036.

Paul, I. (2005). Modelling the distribution of citrus black spot caused by Guignardia citricarpa Kiely. Ph. D. Thesis. Pretoria: University of Pretoria.

Paul, I., van Jaarsveld, A. S., Korsten, L., & Hattingh, V. (2005). The potential global geographical distribution of citrus black spot caused by Guignardia citricarpa Kiely: likelihood of disease establishment in the European Union. Crop Protection, 24, 297–308.

Pebesma, E. J., & Bivand, R. S. (2005). Classes and methods for spatial data in R. R News, 5, 9–13.

Peel, M. C., Finlayson, B. L., & McMahon, T. A. (2007). Updated world map of the Koppen-Geiger climate classification. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, 11, 1633–1644.

Perryman, S. A. M., Clark, S. J., & West, J. S. (2014). Splash dispersal of Phyllosticta citricarpa conidia from infected citrus fruit. Scientific Reports, 4, 6568.

Plant, R. E. (2012). Spatial data analysis in ecology and agriculture using R. Boca Raton: CRC Press.

R-Core-Team (2013). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing.Vienna, Austria. http://www.R-project.org/.

Reuther, W., Webber, B. J., & Batchelor, L. D. (1967). The citrus industry. Vol I History, world distribution, botany and varieties. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Rieux, A., Soubeyrand, S., Bonnot, F., Klein, E. K., Ngando, J. E., Mehl, A., Ravigne, V., Carlier, J., & De Lapeyre de Bellaire, L. (2014). Long-distance wind-dispersal of spores in a fungal plant pathogen: estimation of anisotropic dispersal kernels from an extensive field experiment. PLoS ONE, 9, e103225.

Schubert, T. S., Dewdney, M. M., Peres, N. A., Palm, M. E., Jeyaprakash, A., Sutton, B., Mondal, S. N., Wang, N. Y., Rascoe, J., & Picton, D. D. (2012). First report of citrus black spot caused by Guignardia citricarpa on sweet orange [Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck] in North America. Plant Disease, 96, 1225.

Simberloff, D. (2009). The role of propagule pressure in biological invasions. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 40, 81–102.

Sposito, M. B., Amorim, L., Ribeiro, P. J., Bassanezi, R. B., & Krainski, E. T. (2007). Spatial pattern of trees affected by black spot in citrus groves in Brazil. Plant Disease, 91, 36–40.

Spósito, M. B., Amorim, L., Bassanezi, R. B., Yamamoto, P., Felippe, M. R., & Czermainski, A. B. C. (2011). Relative importance of inoculum sources of Guignardia citricarpa on the citrus black spot epidemic in Brazil. Crop Protection, 30, 1546–1552.

Vicent, A., & García-Jiménez, J. (2008). Risk of establishment of non-indigenous diseases of citrus fruit and foliage in Spain: an approach using meteorological databases and tree canopy climate data. Phytoparasitica, 36, 7–19.

Wager, V. A. (1952). The black spot disease of citrus in South Africa. Science Bulletin of the Department of Agriculture of the Union of South Africa, 303, 1–52.

Whiteside, J. O. (1967). Sources of inoculum of the black spot fungus, Guignardia citricarpa, in infected Rhodesian citrus orchards. The Rhodesia, Zambia and Malawi Journal of Agricultural Research, 5, 171–177.

Yonow, T., Hattingh, V., & de Villiers, M. (2013). CLIMEX modelling of the potential global distribution of the citrus black spot disease caused by Guignardia citricarpa and the risk posed to Europe. Crop Protection, 44, 18–28.

Acknowledgments

We thank V. Monzó (Plug Dayhe S.L.) for georeferencing disease distribution data, J.V. Castelló (IVIA) for retrieving historical references, and L.W Timmer (CREC-IFAS/University of Florida) and M. Pautasso (EFSA) for commenting the manuscript.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

ᅟ

Funding

DC and ALQ are supported by MINECO grant MTM2013-42323-P.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Martínez-Minaya, J., Conesa, D., López-Quílez, A. et al. Climatic distribution of citrus black spot caused by Phyllosticta citricarpa. A historical analysis of disease spread in South Africa. Eur J Plant Pathol 143, 69–83 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10658-015-0666-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10658-015-0666-z