Abstract

We analyze the introduction of capitation taxes as a mean of regulating professional services in a Principal-Agent moral-hazard framework. Although the tax increases cost and lowers participation, we find that it reduces the marginal price associated with quality. The optimal capitation system balances these opposing effects. We use the setup to derive comparative statics results and discuss possible impacts of improvements in ICT on occupational regulation. We find that the results are more ambiguous than often suggested.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

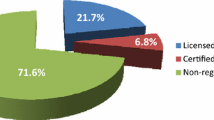

See for instance the report by the US Council on Licensure, Enforcement, and Regulation.CLEAR 2004 (see http://www.clearhq.org/mission). Also for the US, the report states that there are up to 1100 occupations that were either licensed, certified, or registered in at least one State.

While we focus on informational asymmetry to justify regulation, there is also a literature which uses the idea of merit goods and the benefit of public protection; for instance, see Ogus (2004) and the citation therein.

See Akerlof (1970).

See The White House (2015).

The Hamilton Project is an economic policy initiative at the Brooking Institution that was launched in 2006. According to the initiators, “ the Project provides a platform for a broad range of leading economic thinkers to inject innovative and pragmatic policy options into the national debate. The Project offers proposals rooted in evidence and experience, not doctrine and ideology, and brings those ideas to bear on policy debates in relevant and effective ways” (see http://www.hamiltonproject.org/about/).

See for instance Laffont and Martimort (2002).

An alternative would have been to allocate the bargaining power more evenly between the parties. For instance, by using either Nash Bargaining and Rubinstein Bargaining. These alternatives have been explored in the literature, see e.g. Pitchford (1998) and Demougin and Helm (2006).The main conclusion of this literature is that although different distributions of bargaining power affect the respective weights in the trade-offs, it does not fundamentally change the logic nor the direction of the trade-offs found under the standard paradigm. Hence, for the sake of parsimony and ease of comparability, we adopt the usual framework.

We introduced the parameters \(\alpha \) and \(\mu \) for the needs of the comparative static analyzes which follow.

Note that in the context of a risk-neutral agency problem, the restriction to a binary signal is without loss of generality because useful information from any monitoring technology can always be aggregated into a binary variable; see e.g. Demougin and Fluet (1998).

In that example, the agent is subject to random mistakes that follow a Poisson process. The agent’s choice of effort determines the average number of mistakes. The variable \(\theta \) measures the likelihood of verifying a mistake. Finally, due to the risk neutrality of parties, the information is aggregated in a binary proxy where the incentive scheme pays a bonus if and only if no mistake is verified. Naturally, in such a context, improving monitoring means verifying a mistake with a higher likelihood.

See footnote 10.

There are many other alternatives. For instance, one could assume loss aversion which has been shown in experiments to provide a fairly realistic representation of individual preferences. In this type of environment, Herweg et al. (2010) have shown that a binary incentive scheme would emerge endogenously.

For a recent theoretical analysis and an empirical case study, see Demougin and Fabel (2019).

In the more general case where c(x) is a strictly increasing and convex function, we would obtain \(\frac{xc^{\prime }(x)}{\theta }\).

See for instance, Laffont and Martimort (2002) chapter 2.

Analytically, the slope of welfare with respect to quality at the point \(x^{FB}(\alpha )\) is nil. Hence small variations in x around \(x^{FB}(\alpha )\) only have an impact through their second-order derivatives. In contrast, a small reduction in the critical \(\tau ^{c}\) has a direct positive effect on participation and, thus, on welfare. For a similar line of reasoning, see e.g. Laffont and Tirole (1993, p. 467).

Alternatively, it states that the informational content of s has increased; for further discussion of this intuition, see Demougin and Fluet (2001) and footnote 11.

In order to evaluate the derivative, we substituted in (26) the respective definitions of \(X^{c},\tau ^{c}\), and \(\tau _{\phi }^{c}\) from (9), (20) and (21) to obtain

$$\begin{aligned} \left( \alpha v^{\prime }\left( \frac{\theta }{1-\theta }\phi \right) -1\right) \frac{\theta }{1-\theta }+\phi \frac{g(\alpha v\left( \frac{\theta }{1-\theta }\phi \right) -\frac{\theta }{1-\theta }\phi -\phi \ |\ \mu )}{G(\alpha v\left( \frac{\theta }{1-\theta }\phi \right) -\frac{\theta }{1-\theta }\phi -\phi \ |\ \mu )}\left( \left( \alpha v^{\prime }\left( X^{c}\left( \theta ,\phi \right) \right) -1\right) \frac{\theta }{1-\theta }-1\right) =0 \end{aligned}$$and directly applied the implicit function theorem.

Note \(\frac{d}{d\tau }\left[ \frac{g(\tau |\mu )}{G(\tau |\mu )}\right] =\frac{d^{2}}{d\tau ^{2}}\left[ \ln G(\tau |\mu )\right] \) where the RHS is negative since \(g(\tau \ |\ \mu )\) being decreasing in \(\mu \) implies log-concavity (see Bagnoli and Bergstrom (2005), and the brief discussion on page 8)).

Note, however, from basic statistics that while RHRD implies FOSD, the reverse does not hold – e.g. see Hickman (2009). Accordingly, for distributions which do satisfy FOSD but not RHRD it is possible that transaction costs reducing improvements could lead to a reduction in the capitation tax.

References

Adams, Frank A., Ekelund, Robert B., & Jackson, John D. (2002). Occupational licensing of a credence good: The regulation of midwifery. Southern Economic Journal, 69(3), 659–675.

Akerlof, G. A. (1970). The market for lemons: Quality uncertainty and the market mechanism. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 84(3), 488–500.

Angrist, J. D., & Guryan, J. (2008). Does teacher testing raise teacher quality? Evidence from State certification requirements. Economics of Education Review, 27, 483–503.

Bagnoli, M., & Bergstrom, T. (2005). Log-concave probability and its applications. Economic Theory, 26(2), 445–469.

Blair, P. Q., & Fisher, M. (2022). Does occupational licensing reduce value creation on digital platforms? National Bureau of Economic Research. WP30388.

Boek, S. (2008). Taxation in the later roman empire: A study on the character of the late antique economy. Thesis of Ancient History, Leiden University.

Buddin, R., & Zamarro, G. (2008). Teacher qualifications and student achievement in Urban elementary schools. Journal of Urban Economics, 66(2), 103–115.

Canton, E.,D. Ciriaci & I. Solera (2014). The economic impact of professional services Liberalisation, Economic Papers 533 of the European Commission.

Carpenter, C. G., & Stephenson, F. E. (2006). The 150-hour rule as a barrier to entering public accountancy. Journal of Labor Research, 27(1), 115–126.

Carpenter, D. (2008). Regulation through titling laws: A case study of occupational regulation. Regulation and Governance, 2(3), 340–359.

Carpenter, D. (2008). Testing the utility of licensing: Evidence from a field experiment on occupational regulation. Journal of Applied Business and Economics, 13(2), 28–41.

Chevalier, J., & Morton, F. S. (2008). State casket sales restrictions: A pointless undertaking? Journal of Law and Economics, 51(1), 1–23.

Chung, B. W. (2022). The costs and potential benefits of occupational licensing: A case of real estate license reform. Labour Economics, 76, 102172.

Demougin, D., & Fabel, O. (2019). The nexus between contract duration and the use of formal and informal incentive pay. Labour, 33(3), 351–370.

Demougin, D., & Fluet, C. (1998). Mechanism sufficient statistic in the risk-neutral agency problem. Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics, 154(4), 622–639.

Demougin, D., & Fluet, C. (2001). Monitoring versus incentives. The European Economic Review, 45(9), 1741–1764.

Demougin, D., & Helm, C. (2006). Moral hazard and bargaining power. German Economic Review, 7(4), 463–470.

Farronato, C., Fradkin, A., Larsen, B. & Brynjolfsson, E. (2020). Consumer protection in an online World: An analysis of occupational licensing. National Bureau of Economic Research. WP26601.

Federman, M. N., Harrington, D. E., & Krynski, K. J. (2006). The impact of state licensing regulations on low-skilled immigrants: The case of Vietnamese manicurists. American Economic Review, 96(2), 237–241.

Friedman, M. (1962). Capitalism and freedom. University of Chicago Press.

Jacob, J., & Murray, D. (2006). Supply-side effects of the 150-Hour educational requirement to CPA licensing. Journal of Regulatory Economics, 30(2), 159–178.

Jackson, R. E. (2006). Post-graduate educational requirements and entry into the CPA profession. Journal of Labor Research, 27(1), 101–114.

Hadfield, G. K. (2000). The price of law: How the market for lawyers distorts the justice system. Michigan Law Review, 98, 953–1006.

Herweg, Fabian, Muller, Daniel, & Weinschenk, Philipp. (2010). Binary payment schemes: Moral hazard and loss aversion. American Economic Review, 100(5), 2451–77.

Hickman, B. R. (2009). Introduction to probability theory for graduate economics. http://home.uchicago.edu/hickmanbr/uploads/PT_REVIEW_CH4.pdf.

Hubbard, T. N. (2000). The demand for monitoring technologies: The case of trucking. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 115(2), 533–560.

Hubbard, T. N. (2003). Information, decisions and productivity: On board computers and capacity utilization in trucking. American Economic Review, 93(4), 1328–1353.

Humphris, M., & Koumenta, A. (2015). The effects of occupational licensing on employment, skills and quality: A case study of two occupations in the UK. Queen Mary University of London.

Kleiner, M. M. (2017). Regulating access to work in the gig labor market: The case of Uber. Employment Research, 24(3), 4–6.

Kleiner, M. M. (2015). Reforming occupational licensing policies, the Hamilton project. Brookings, Discussion Paper 01-2015.

Kleiner, M. M. (2006). Licensing occupations: Ensuring quality Or restricting competition? Upjohn Institute.

Kleiner, M. M. (2000). Occupational Licensing. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 14(4), 189–202.

Kleiner, M. M., & Koumenta, M. (2022). Grease or Grit? International Case Studies of Occupational Licensing and Its Effects on Efficiency and Quality. W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research.

Kleiner, M. M., & Soltas, E. J. (2019). A welfare analysis of occupational licensing in US States. Review of Economic Studies Forthcoming

Kleiner, M. M. & Vorotnikov, E. (2016). Analyzing occupational licensing among the States. Mimeo.

Kleiner, M. M. & Krueger, A. B. (2011). Analyzing the extent and influence of occupational licensing on the labor market. Discussion paper series //Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit, No. 5505, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:101:1-201104113785.

Kleiner, M. M., & Krueger, A. B. (2013). Analyzing the extent and influence of occupational licensing on the labor market. Journal of Labor Economics, 31(2), 173–202.

Kleiner, M. M. & R. M. Todd (2009). Mortgage broker regulations that matter: Analyzing earnings, employment, and outcomes for consumers. In D. H. Autor (ed) NBER book: Studies of Labor Market Intermediation: pp. 183 - 231.

Kleiner, M. M., & Kudrle, R. T. (2000). Does regulation affect economic outcomes: The case of dentistry. Journal of Law and Economics, 43(2), 547–582.

Laffont, J.-J. & Martimort, D. (2002). The Theory of Incentives: The Principal–Agent Model. Princeton University Press.

Laffont, J.-J., & Tirole, J. (1993). A Theory of Incentives in Procurement and Regulation. MIT Press.

Leland, H. E. (1979). Quacks, lemons, and licensing: A theory of minimum quality standards. Journal of Political Economy,87(6), 1328–1346.

Milgrom, P. (1981). Good news and bad news: Representation theorems and applications. Bell Journal of Economics,12(2), 380–390.

Miozzo, M., & Ramirez, M. (2003). Services innovation and the transformation of work: The case of UK telecommunications. New Technology, Work and Employment 18(1), 62–79.

Murphy, K. J. (1998). Executive compensation. Handbook of Labor Economics 3(B): 2485–2563.

Ogus, A. (2004). Regulation: Legal form and economic theory. Second Edition.Hart Publishing.

Pitchford, R. (1998). Moral hazard and limited liability: The real effects of contract bargaining. Economics Letters, 61(2), 251–259.

Posner, R. A. (1974). Theories of economic regulation. Bell Journal of Economics 5(2), 335–358.

Shapiro, C. (1986). Investment, moral-hazard and occupational licensing. The Review of Economics Studies LIII: 843–862.

Stigler, G. (1971). The theory of economic regulation. Bell Journal of Economics and Management Science, 2(1), 3–21.

The White House (2015). Occupational licensing: A framework for policymakers. report prepared by the department of the treasury office of economic policy, the council of economic advisers and the department of labor.

Thornton, R. J., Timmons, E. & Kukaev, I. (2021). The De-licensing of occupations in the United States: A shifting trend? Labor Law Journal.

White, W. D. (1978). The impact of occupational licensing of clinical laboratory personnel. Journal of Human Resources 13(1), 91–102.

White, W. D. (1980). Mandatory licensing of registered nurses: Introduction and impact. In S. Rottenberg (Ed.) Occupational licensing and Regulation pp. 47-72.

Acknowledgements

The authors are very grateful to Benjamin Bental, Yair Osheroff and the referees for their suggestions and numerous recent references. In particular, an earlier version referred to “ capitation tax” as “ capitation fee” which could be confused with doctor’s remuneration used in some countries, while “ tax” naturally conveys the idea that the payment is made to the government.

Funding

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Proof of Proposition 1

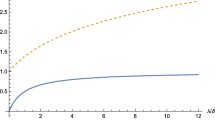

Suppose that \(X^{c}\left( \theta ,\phi \right) \le x^{SB}(\alpha ,\theta )\). Geometrically, this case is represented by Fig. 7a. Accordingly, we have \(x^{*}\left( \alpha ,\theta ,\phi \right) =x^{SB}(\alpha ,\theta )\). Suppose that \(X^{c}\left( \theta ,\phi \right) \ge x^{FB}(\alpha )\) which corresponds to Fig. 7b. Hence, we have \(x^{*}\left( \alpha ,\theta ,\phi \right) =x^{FB}(\alpha ).\)

Finally, consider the intermediate case \(x^{SB}(\alpha ,\theta )<X^{c}\left( \theta ,\phi \right) <x^{FB}(\alpha )\). By concavity of \(V(\cdot )\) with \(X^{c}\left( \theta ,\phi \right) <x^{FB}(\alpha )\), we know \(\alpha V^{\prime }(X^{c}\left( \theta ,\phi \right) )-1>0\) and, thus, \(x^{*}\left( \alpha ,\theta ,\phi \right) \ge X^{c}\left( \theta ,\phi \right) \). Also by concavity, we know \(x^{SB}(\alpha ,\theta )<X^{c}\left( \theta ,\phi \right) \) implies \(\alpha V^{\prime }(X^{c}\left( \theta ,\phi \right) )-\theta ^{-1}<0\) and therefore \(x^{*}\left( \alpha ,\theta ,\phi \right) \le X^{c}\left( \theta ,\phi \right) \). In short, it implies \(x^{*}\left( \alpha ,\theta ,\phi \right) =X^{c}\left( \theta ,\phi \right) \). \(\square \)

Proof of Proposition 3

We proceed in two steps.

-

1.

Consider any \(\phi \) with \(x^{*}\left( \alpha ,\theta ,\phi \right) <X^{c}\left( \theta ,\phi \right) \). We are in a situation as in Fig. 7b so that participating consumers set \(x^{*}\left( \alpha ,\theta ,\phi \right) =x^{FB}(\alpha )\). Keeping in mind that (16) is not satisfied, there is a critical transaction cost which is defined by:

$$\begin{aligned} \tau ^{c}\left( \alpha ,\theta ,\phi \right) =\alpha v(x^{FB}(\alpha ))-x^{FB}(\alpha )-\phi \end{aligned}$$(31)Now, consider an infinitesimal reduction in \(\phi \). By construction, this would not affect the quality implemented, but it would marginally raise \(\tau ^{c}\). Hence, it would increase the total number of participating consumers, thereby, raising the total sum of trade gains. Consequently, at \(\phi ^{*}\left( \alpha ,\theta ,\mu \right) \), we must have \(x^{*}\left( \alpha ,\theta ,\phi ^{*}\right) \ge X^{c}\left( \theta ,\phi ^{*}\right) \).

-

2.

Consider any \(\phi \) with \(x^{*}\left( \alpha ,\theta ,\phi \right) >X^{c}\left( \alpha ,\theta ,\phi \right) \). This corresponds to a situation similar to the one represented in Fig. 6a. By (13) it implies that \(x^{*}\left( \alpha ,\theta ,\phi ^{*}\right) =x^{SB}(\alpha ,\theta )\) and, thus, \(x^{SB}(\alpha ,\theta )>X^{c}\left( \alpha ,\theta ,\phi \right) \). Consider an infinitesimal increase in the capitation to \(\phi +\varepsilon \) with \(\varepsilon >0\). It has no effect on the quality implemented – which remains at \(x^{SB}(\alpha ,\theta )\) – and no impact on participation. Hence, we have \(W\left( \phi ;\alpha ,\theta ,\mu \right) =W\left( \phi +\varepsilon ;\alpha ,\theta ,\mu \right) \). The same process will continue until we reach capitation tax \(\phi =\phi ^{SB}\left( \alpha ,\theta \right) \) which is implicitly defined so that the kink of the cost function \(C(x;\theta ,\phi ^{SB})\) occurs exactly at \(x^{SB}(\alpha ,\theta )\). Accordingly, we have \(W\left( \phi ;\alpha ,\theta ,\mu \right) =W\left( \phi ^{SB};\alpha ,\theta ,\mu \right) \). We now argue that \(W_{\phi }\left( \phi ^{SB};\alpha ,\theta ,\mu \right) >0\). Consider an additional infinitesimal increase in capitation at \(\phi ^{SB}\left( \alpha ,\theta \right) \). By (9) it forces participating consumers to marginally raise the quality they induce. This generates a first-order effect in quality. However, it has only a second-order effect on participation . Hence, \(x^{*}\left( \alpha ,\theta ,\phi \right) >X^{c}\left( \theta ,\phi \right) \) can never be optimal with the result that \(x^{*}\left( \alpha ,\theta ,\phi ^{*}\right) \le X^{c}\left( \theta ,\phi ^{*}\right) \).

Taking points 1 and 2 together confirms (i). Using (i), point 1 implies \(X^{c}\left( \theta ,\phi ^{*}\right)\, \le x^{FB}(\alpha )\) and point 2 validates \(x^{SB}(\alpha ,\theta )\le X^{c}\left( \theta ,\phi ^{*}\right) \). \(\square \)

Proof of Proposition 5

Slightly abusing notation, the first-order condition from (24) becomes:

Taking (20) into account and factorizing allows us to rewrite (32) as follows:

From the definition of \(X^{c}\) in (9), we have \(X_{\phi }^{c}>0\). Moreover, by Proposition 4 we know \(\tau _{\phi }^{c}\le 0\). Hence, we have \(\alpha v^{\prime }\left( X^{c}\right) \ge 1\) or equivalently \(\phi ^{*}\left( \alpha ,\theta \right) \le \phi ^{FB}\left( \alpha ,\theta \right) \). Note that the equality is not feasible since at \(\phi =\phi ^{FB}\left( \alpha ,\theta \right) \), we have \(\tau _{\phi }^{c}<0\). Using (22) and (9), the equality (32) can be equivalently rewritten as

which implies \(\alpha v^{\prime }\left( X^{c}\right) <\theta ^{-1}\). Accordingly, by (23) we have \(\phi ^{*}\left( \alpha ,\theta \right) >\phi ^{SB}\left( \alpha ,\theta \right) \). \(\square \)

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Deffains, B., Demougin, D. Capitation taxes and the regulation of professional services. Eur J Law Econ 55, 167–193 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10657-023-09762-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10657-023-09762-z