Abstract

Oral examinations are a fairly common way of evaluating candidates in professional certification settings. This paper explores the objectivity of the process followed for hiring judges in Greece, with an emphasis on the effect of gender on the hiring decision. Using data for the years 2008–2014, I find statistically significant and robust evidence of female candidates performing slightly worse than male candidates in the oral examination. The mechanism that explains this difference (discrimination, difference in skills, etc.) is not clear. Nevertheless, this result stresses the importance of applying enhanced meritocratic safeguards to oral examinations, especially when a career as a judge is at stake.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Interrater reliability is the correlation of one examiner’s ratings with those of another.

However, see also Lunz and Bashook (2008), who do not find such an effect.

Interestingly, self-esteem was found to be negatively correlated with outcomes for both genders (Mellanby et al. 2013).

One important limitation of the above result is that the written scores that I have at my disposal are only for those candidates who cleared the threshold in order to participate in the oral part. The effect of this limitation will be further discussed below.

The administrative court adjudicates disputes between citizens and the government.

In my sample, out of 18 exams, only in two cases were there fewer candidates than open positions at the stage of the oral examination.

Prior to 2011, there were only two types, one for civil and criminal judges and one for administrative judges.

Prior to 2009, there was no mandatory foreign language test. Candidates had the option to be tested on one or two of the four foreign languages mentioned.

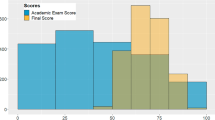

Prior to 2011, the written and the oral parts counted equally for a candidate’s final grade (each 50 percent). Moreover, the bonus for each foreign language was 0.2 (foreign languages were optional in 2008, but at least one was mandatory from 2009 onward) and there was no bonus for a graduate degree.

In the same vein, Goldin and Rouse (2000) identify a causal link between gender and getting hired by a symphonic orchestra by comparing “blind” auditions (in which a screen is used to hide the identity of the musician from the jury) and non-blind ones. Similar links between labor market outcomes and attributes such as race or looks have also been established in the literature (see, e.g., Bertrand and Mullainathan (2004) and Hamermesh and Biddle (1994)), albeit in a more experimental setting.

Note also the larger and significant effect of the “related” variable on the probability of success, an effect that is larger when the oral score is omitted.

Note, though, that in the left column the effect of the omitted variable (oral score) is captured in part by the “male” coefficient showing an indiscernible positive effect on the probability of success for men. In the right column, the effect of the omitted variable (written score) on the “male” coefficient is captured in part by the “male” coefficient showing a similar indiscernible negative effect on the probability of success for men.

The authors found that the gender composition of examination committees had an impact on the performance of male and female candidates. In that particular case similarity of gender hurt the performance of a candidate. However, this type of mechanism can be revealed only at the exam-committee level and not at the individual-candidate level. However, as noted, I only have access to 18 exams out of which I was able to verify the gender composition of 13 committees. Moreover, the gender variation of the committees is not considerable. In six out of the 13 committees there were no women examiners. In four committees there was one woman, in two committees two women, and in one committee three women. There was a female chair in four committees. As a result, because of the lack of a sufficient number of committees and also of gender variation within the committees, I am not in a position to test the committee-composition mechanism.

One should note, though, that there may be more underlying factors which I cannot account for given the limitations of the data set.

Of course, one could argue that knowledge obtained in a graduate degree could be more helpful in an oral test than a written test. However, the counter argument to that would be that the oral part is much shorter than the 20-hour written part (five sessions times four hours each), therefore, if anything, candidates have more room to display the skills acquired in their graduate degrees in the written part.

It should be noted, though, that anecdotal evidence suggests that several of the non-related candidates were also raised in similar environments, such as a family in which one or both parents are lawyers.

Another possible explanation could be that the examiners become increasingly lenient as the examination progresses, perhaps due to tiredness or lowering of standards.

An alternative solution would be to bar the candidates who will take the examination later from being in the room when the first candidates take it. However, this method reduces the transparency of the process and would cause other problems.

References

Anastakis, D. J., Cohen, R., & Reznick, R. K. (1991). The structured oral examination as a method for assessing surgical residents. American Journal of Surgery, 162(1), 67–70.

Antonovics, K., & Knight, B. G. (2009). A new look at racial profiling: Evidence from the Boston police department. Review of Economics and Statistics, 91(1), 163–177.

Arrow, K. (1973). The Theory of Discrimination. In O. Ashenfelter & A. Rees (Eds.), Discrimination in labor markets (pp. 3–33). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Bagues, M. F., & Esteve-Volart, B. (2010). Can gender parity break the glass ceiling? Evidence from a repeated randomized experiment. Review of Economic Studies, 77(4), 1301–1328.

Becker, G. (1971). The economics of discrimination. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bertrand, M., & Mullainathan, S. (2004). Are Emily and Greg more employable than Lakisha and Jamal? A field experiment on labor market discrimination. American Economic Review, 94(4), 991–1013.

Broder, I. E. (1993). Review of NSF economics proposals: Gender and institutional patterns. American Economic Review, 83(4), 964–970.

Chaudhuri, A. (2012). Gender and corruption: A survey of the experimental evidence. Research in Experimental Economics, 15, 13–49.

Dharmapala, D., & Ross, S. L. (2004). Racial bias in motor vehicle searches: Additional theory and evidence. Contributions in Economic Analysis and Policy, 3(1), 1–23.

Dollar, D., Fisman, R., & Gatti, R. (2001). Are women really the fairer sex? Corruption and women in government. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 46(4), 423–429.

Farsides, T., & Woodfield, R. (2007). Individual and gender differences in good and first-class undergraduate degree performance. British Journal of Psychology, 98(3), 467–483.

Furnham, A., & Chamorro-Premuzic, T. (2005). Individual differences and beliefs concerning preference for university assessment methods. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 35(9), 1968–1994.

Gerdeman, A. M. (1998). Understanding the oral examination process in professional certification examinations. Ph.D. thesis.

Goldberg, C. B. (2005). Relational demography and similarity-attraction in interview assessments and subsequent offer decisions are we missing something? Group and Organization Management, 30(6), 597–624.

Goldin, C., & Rouse, C. (2000). Orchestrating impartiality: The impact of “blind” auditions on female musicians. American Economic Review, 90(4), 715–741.

Graves, L. M., & Powell, G. N. (1995). The effect of sex similarity on recruiters’ evaluations of applicants: A test of the similarity-attraction paradigm. Personnel Psychology, 48(1), 85–98.

Graves, L. M., & Powell, G. N. (1996). Sex similarity, quality of the employment interview and recruiters’ evaluation of actual applicants. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 69(3), 243–261.

Hamermesh, D., & Biddle, J. E. (1994). Beauty and the labor market. American Economic Review, 84(5), 1174–1194.

Holland, P. W. (1986). Statistics and causal inference. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 81(396), 945–960.

Houston, J. E., & Myford, C. M. (2009). Judges’ perception of candidates’ organization and communication, in relation to oral certification examination ratings. Academic Medicine, 84(11), 1603–1609.

Houston, J. E., & Smith, E. V. (2008). Relationship of candidate communication and organization skills to oral certification examination scores. Evaluation and the Health Professions, 31(4), 404–418.

Knowles, J., Persico, N., & Todd, P. (2001). Racial bias in motor-vehicle searches: Theory and evidence. Journal of Political Economy, 109(1), 203–229.

Lavy, V. (2008). Do gender stereotypes reduce girls’ or boys’ human capital outcomes? Evidence from a natural experiment. Journal of Public Economics, 92(10), 2083–2105.

Levine, H. G., & McGuire, C. H. (1970). The validity and reliability of oral examinations in assessing cognitive skills in medicine. Journal of Educational Measurement, 7(2), 63–74.

Lunz, M. E., & Bashook, P. G. (2008). Relationship between candidate communication ability and oral certification examination scores. Medical Education, 42(12), 1227–1233.

Mellanby, J., Martin, M., & O’Doherty, J. (2000). The gender gap in final examination results at Oxford University. British Journal of Psychology, 91(3), 377–390.

Mellanby, J., Zimdars, A., & Cortina-Borja, M. (2013). Sex differences in degree performance at the University of Oxford. Learning and Individual Differences, 26, 103–111.

Petersen, T., Saporta, I., & Seidel, M.-D. L. (2000). Offering a job: Meritocracy and social networks. American Journal of Sociology, 106(3), 763–816.

Price, J., & Wolfers, J. (2010). Racial discrimination among NBA referees. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 125(4), 1859–1887.

Pulakos, E. D., White, L. A., Oppler, S. H., & Borman, W. C. (1989). Examination of race and sex effects on performance ratings. Journal of Applied Psychology, 74(5), 770.

Raymond, M. R., Webb, L. C., & Houston, W. M. (1991). Correcting performance-rating errors in oral examinations. Evaluation and the Health Professions, 14(1), 100–122.

Reis, S. B., Young, I. P., & Jury, J. C. (1999). Female administrators: A crack in the glass ceiling. Journal of Personnel Evaluation in Education, 13(1), 71–82.

Rivas, M. F. (2013). An experiment on corruption and gender. Bulletin of Economic Research, 65(1), 10–42.

Roberts, C., Sarangi, S., Southgate, L., Wakeford, R., & Wass, V. (2000). Oral examinations—equal opportunities, ethnicity, and fairness in the MRCGP. British Medical Journal, 320–374(7231), 370.

Rubin, D. B. (1974). Estimating causal effects of treatments in randomized and nonrandomized studies. Journal of Educational Psychology, 66(5), 688–701.

Santos-Pinto, L. (2012). Labor market signaling and self-confidence: Wage compression and the gender pay gap. Journal of Labor Economics, 30(4), 873–914.

Seddon, G., & Pedrosa, M. (1990). Non-verbal effects in oral testing. British Educational Research Journal, 16(3), 305–310.

Swamy, A., Knack, S., Lee, Y., & Azfar, O. (2001). Gender and corruption. Journal of Development Economics, 64(1), 25–55.

Thomas, C. S., Mellsop, G., Callender, K., Crawshaw, J., Ellis, P., Hall, A., MacDonald, J., Silfverski, P., - old, & Romans-Clarkson, S. (1993). The oral examination: A study of academic and non-academic factors. Medical Education, 27(5), 433–439.

Wakeford, R., Farooqi, A., Rashid, A., & Southgate, L. (1992). Does the MRCGP examination discriminate against Asian doctors? British Medical Journal, 305(6845), 92.

Wass, V., Wakeford, R., Neighbour, R., & Van der Vleuten, C. (2003). Achieving acceptable reliability in oral examinations: An analysis of the Royal College of General Practitioners membership examination’s oral component. Medical Education, 37(2), 126–131.

Yaphe, J., & Street, S. (2003). How do examiners decide? A qualitative study of the process of decision making in the oral examination component of the MRCGP examination. Medical Education, 37(9), 764–771.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

I would like to thank wholeheartedly my friend Athanasios Anagnostopoulos, who had the initial idea for this paper. I am also grateful to Ben Anderson, Michael O’Hara, Dean Scrimgeour, Robert Turner, and two anonymous referees for their helpful comments and suggestions. Adib Chowdhury provided excellent research assistance.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Georgiou, G. Are oral examinations objective? Evidence from the hiring process for judges in Greece. Eur J Law Econ 44, 217–239 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10657-016-9545-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10657-016-9545-0