Abstract

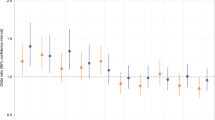

Studies report increased risk of congenital heart defects (CHD) in the offspring of mothers with diabetes, where high blood glucose levels might confer the risk. We explored the association between intake of sucrose-sweetened soft beverages during pregnancy and risk of CHD. Prospective cohort data with 88,514 pregnant women participating in the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study was linked with information on infant CHD diagnoses from national health registers and the Cardiovascular Diseases in Norway Project. Risk ratios were estimated by fitting generalized linear models and generalized additive models. The prevalence of children with CHD was 12/1000 in this cohort (1049/88,514). Among these, 201 had severe and 848 had non-severe CHD (patent ductus arteriosus; valvular pulmonary stenosis; ventricular septal defect; atrial septal defect). Only non-severe CHD was associated with sucrose-sweetened soft beverages. The adjusted risk ratios (aRR) for non-severe CHD was 1.30 (95% CI 1.07–1.58) for women who consumed 25–70 ml/day and 1.27 (95% CI 1.06–1.52) for women who consumed ≥ 70 ml/day when compared to those drinking ≤ 25 ml/day. Dose–response analyses revealed an association between the risk of non-severe CHD and the increasing exposure to sucrose-sweetened soft beverages, especially for septal defects with aRR = 1.26 (95% CI 1.07–1.47) per tenfold increase in daily intake dose. The findings persisted after adjustment for maternal diabetes or after excluding mothers with diabetes (n = 19). Fruit juices, cordial beverages and artificial sweeteners showed no associations with CHD. The findings suggest that sucrose-sweetened soft beverages may affect the CHD risk in offspring.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Dolk H, Loane M, Garne E. Congenital heart defects in Europe. Circulation. 2011;123(8):841–9.

Hoffman JIE, Kaplan S. The incidence of congenital heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39(12):1890–900.

Botto LD, Lin AE, Riehle-Colarusso T, Malik S, Correa A, National Birth Defects Prevention S. Seeking causes: classifying and evaluating congenital heart defects in etiologic studies. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2007;79(10):714–27.

Liu S, Joseph KS, Lisonkova S, Rouleau J, Van den Hof M, Sauve R, et al. Association between maternal chronic conditions and congenital heart defects: a population-based cohort study. Circulation. 2013;137(5):583–9.

Wilson PD, Loffredo CA, Correa-Villaseñor A, Ferencz C. Attributable fraction for cardiac malformations. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;148(5):414–23.

Fung A, Manlhiot C, Naik S, Rosenberg H, Smythe J, Lougheed J, et al. Impact of prenatal risk factors on congenital heart disease in the current era. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2(3):e000064.

Stoll C, Alembik Y, Roth MP, Dott B, De Geeter B. Risk factors in congenital heart disease. Eur J Epidemiol. 1989;5(3):382–91.

Wilson PD, Correa-Villaseñor A, Loffredo CA, Ferencz C. Temporal trends in prevalence of cardiovascular malformations in Maryland and the District of Columbia, 1981–1988. Epidemiology. 1993;4(3):259–65.

Lisowski LA, Verheijen PM, Copel JA, Kleinman CS, Wassink S, Visser GHA, et al. Congenital heart disease in pregnancies complicated by maternal diabetes mellitus. Herz. 2010;35(1):19–26.

Shaw JE, Sicree RA, Zimmet PZ. Global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2010 and 2030. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;87(1):4–14.

Loffredo CA, Wilson PD, Ferencz C. Maternal diabetes: an independent risk factor for major cardiovascular malformations with increased mortality of affected infants. Teratology. 2001;64(2):98–106.

Sulo G, Igland J, Vollset SE, Nygǻrd O, Øyen N, Tell GS. Cardiovascular disease and diabetes mellitus in Norway during 1994–2009 CVDNOR—a nationwide research project. Norsk Epidemiol. 2013;23(1):101–7.

Wren C, Birrell G, Hawthorne G. Cardiovascular malformations in infants of diabetic mothers. Heart. 2003;89(10):1217.

Øyen N, Diaz LJ, Leirgul E, Boyd HA, Priest J, Mathiesen ER, et al. Pre-pregnancy diabetes and offspring risk of congenital heart disease: a nation-wide cohort study. Circulation. 2016;137(5):2243–53.

Åberg A, Westbom L, Källén B. Congenital malformations among infants whose mothers had gestational diabetes or preexisting diabetes. Early Hum Dev. 2001;61(2):85–95.

Jenkins KJ, Correa A, Feinstein JA, Botto L, Britt AE, Daniels SR, et al. Noninherited risk factors and congenital cardiovascular defects: current knowledge. Circulation. 2007;115(23):2995.

Meyer-Wittkopf M, Simpson JM, Sharland GK. Incidence of congenital heart defects in fetuses of diabetic mothers: a retrospective study of 326 cases. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1996;8(1):8–10.

Mohammed OJ, Latif ML, Pratten MK. Diabetes-induced effects on cardiomyocytes in chick embryonic heart micromass and mouse embryonic D3 differentiated stem cells. Reprod Toxicol. 2017;69:242–53.

Ramos-Arroyo MA, Rodriguez-Pinilla E, Cordero JF. Maternal diabetes: the risk for specific birth defects. Eur J Epidemiol. 1992;8(4):503–8.

Group THSCR. Hyperglycemia and adverse pregnancy outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(19):1991–2002.

Priest JR, Yang W, Reaven G, Knowles JW, Shaw GM. Maternal midpregnancy glucose levels and risk of congenital heart disease in offspring. JAMA Pediatrics. 2015;169(12):1112–6.

Blue GM, Kirk EP, Sholler GF, Harvey RP, Winlaw DS. Congenital heart disease: current knowledge about causes and inheritance. Med J Aust. 2012;197(3):155–9.

Lee AT, Reis D, Eriksson UJ. Hyperglycemia-induced embryonic dysmorphogenesis correlates with genomic DNA mutation frequency in vitro and in vivo. Diabetes. 1999;48(2):371–6.

Norwegian Directorate of Health. Utviklingen i norsk kosthold. 2015. Available online at www.helsedirektoratet.no/publikasjoner.

Øverby NC, Lillegaard ITL, Johansson L, Andersen LF. High intake of added sugar among Norwegian children and adolescents. Public Health Nutr. 2004;7(2):285–93.

Imamura F, O’Connor L, Ye Z, Mursu J, Hayashino Y, Bhupathiraju SN, et al. Consumption of sugar sweetened beverages, artificially sweetened beverages, and fruit juice and incidence of type 2 diabetes: systematic review, meta-analysis, and estimation of population attributable fraction. BMJ Brit Med J. 2015;351:p.h3576.

Malik VS, Popkin BM, Bray GA, Després J-P, Hu FB. Sugar-sweetened beverages, obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease risk. Circulation. 2010;121(11):1356.

Malik VS, Schulze MB, Hu FB. Intake of sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain: a systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84(2):274–88.

Henriksen T. Nutrition and pregnancy outcome. Nutr Rev. 2006;64(Suppl 2):19–23.

Martínez-Frías ML, Frías JP, Bermejo E, Rodríguez-Pinilla E, Prieto L, Frías JL. Pre-gestational maternal body mass index predicts an increased risk of congenital malformations in infants of mothers with gestational diabetes. Diabet Med. 2005;22(6):775–81.

Watkins ML, Rasmussen SA, Honein MA, Botto LD, Moore CA. Maternal obesity and risk for birth defects. Pediatrics. 2003;111(Supplement 1):1152–8.

Leirgul E, Brodwall K, Greve G, Vollset SE, Holmstrøm H, Tell GS, et al. Maternal diabetes, birth weight, and neonatal risk of congenital heart defects in Norway, 1994–2009. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(5):1116–25.

Parker SE, Werler MM, Shaw GM, Anderka M, Yazdy MM. Dietary glycemic index and the risk of birth defects. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;176(12):1110–20.

HAPO Study Cooperative Research Group, Metzger BE, Lowe LP, Dyer AR, Trimble ER, Chaovarindr U, Coustan DR, Hadden DR, McCance DR, Hod M, et al. Hyperglycemia and adverse pregnancy outcome. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1991–2002.

Magnus P, Irgens LM, Haug K, Nystad W, Skjærven R, Stoltenberg C, et al. Cohort profile: the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study (MoBa). Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35(5):1146–50.

Magnus P, Birke C, Vejrup K, Haugan A, Alsaker E, Daltveit AK, et al. Cohort profile update: the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study (MoBa). Int J Epidemiol. 2016;35(5):1146–50.

Irgens LM. The Medical Birth Registry of Norway. Epidemiological research and surveillance throughout 30 years. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2000;79(6):435–9.

Leirgul E, Fomina T, Brodwall K, Greve G, Holmstrøm H, Vollset SE, et al. Birth prevalence of congenital heart defects in Norway 1994–2009—a nationwide study. Am Heart J. 2014;168(6):956–64.

Hagemo PS. BERTE—a database for children with congenital heart defects. Stud Health Technol Inf. 1994;14:98–101.

Øyen N, Poulsen G, Boyd HA, Wohlfahrt J, Jensen PKA, Melbye M. National time trends in congenital heart defects, Denmark, 1977–2005. Am Heart J. 2009;157(3):467-73.e1.

Strand BH, Dalgard OS, Tambs K, Rognerud M. Measuring the mental health status of the Norwegian population: a comparison of the instruments SCL-25, SCL-10, SCL-5 and MHI-5 (SF-36). Nord J Psychiatry. 2003;57(2):113–8.

Hastie T, Tibshirani R. Generalized additive models. 1st ed. Boca Raton: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 1990.

R CT. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna. https://www.R-project.org/2017.

Yoshida M, McKeown NM, Rogers G, Meigs JB, Saltzman E, D’Agostino R, et al. Surrogate markers of insulin resistance are associated with consumption of sugar-sweetened drinks and fruit juice in middle and older-aged adults. J Nutr. 2007;137(9):2121–7.

Schaefer EJ, Gleason JA, Dansinger ML. Dietary fructose and glucose differentially affect lipid and glucose homeostasis. J Nutr. 2009;139(6):1257–62.

Rippe JM, Angelopoulos TJ. Sucrose, high-fructose corn syrup, and fructose, their metabolism and potential health effects: what do we really know? Adv Nutr. 2013;4(2):236–45.

Palmer JR, Boggs DA, Krishnan S, Hu FB, Singer M, Rosenberg L. Sugar-sweetened beverages and incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus in african american women. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(14):1487–92.

Olafsdottir AS, Thorsdottir I, Gunnarsdottir I, Thorgeirsdottir H, Steingrimsdottir L. Comparison of women’s diet assessed by FFQs and 24-Hour recalls with and without underreporters: associations with biomarkers. Ann Nutr Metab. 2006;50(5):450–60.

Brantsaeter AL, Haugen M, Alexander J, Meltzer HM. Validity of a new food frequency questionnaire for pregnant women in the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study (MoBa). Matern Child Nutr. 2008;4(1):28–43.

Popkin BM, Nielsen SJ. The sweetening of the world’s diet. Obes Res. 2003;11(11):1325–32.

Acknowledgements

MTGD has received funding from an unrestricted grant from Oak Foundation, Geneva, Switzerland. The study sponsors were not involved in the study design; analysis, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication. This work was partly supported by the Research Council of Norway through its Centres of Excellence funding scheme, Project No. 262700. Dr. Øyen was funded by grants from Research Council of Norway (190858/V50) and Western Norway Regional Health Authorities (911734). Tatiana Fomina, Department of Global Health and Primary Care, University of Bergen, Norway, did the quality assurance of data and programmed the algorithm that maps congenital heart defects into embryologically-related defect phenotypes. We thank all the participating families in Norway who took part in this cohort study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MTGD, NØ and PM designed the study. MTGD and HG analyzed the data and MTGD drafted the paper. Authors participated in project meetings at which the analysis plan and data interpretation were discussed. All authors were responsible for interpretation of data and critically revised the article for important intellectual content.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest

Ethical approval

Written informed consent was obtained from all participating women, and the study has been approved by the Regional Committee for Ethics in Medical Research and the Data Inspectorate.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dale, M.T.G., Magnus, P., Leirgul, E. et al. Intake of sucrose-sweetened soft beverages during pregnancy and risk of congenital heart defects (CHD) in offspring: a Norwegian pregnancy cohort study. Eur J Epidemiol 34, 383–396 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-019-00480-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-019-00480-y