Abstract

Language, which plays a special role for the learning of mathematics, is investigated in this article for the specific discourse practice of explaining during whole-class discussions: On the one hand, explaining is a medium for learning since school cannot be thought of without communication. On the other hand, students at the beginning of secondary school are still in the process of language acquisition and are also still learning how to communicate mathematically. Thus, students are learning to explain in mathema-tics classrooms. This empirical study focuses on the overall question of how discourse competence, participation in classroom discourse, and mathematical learning opportunities are related. For that purpose, the approach of Interactional Discourse Analysis is introduced to mathematics education research and coordinated with the Interactional-Epistemic Perspective from mathematics education. The relevance of explaining is shown theoretically and empirically and a description is given of how limited discourse competence and limited epistemic participation proceed across situations.

Similar content being viewed by others

As many researchers have emphasized (e.g., Pimm, 1987), language is an important learning medium in mathematics classrooms. Statistical studies repeatedly have shown that students, including multilingual and monolingual students, with higher language proficiency outperform students with lower language proficiency (e.g., Haag, Heppt, Stanat, Kuhl, & Pant, 2013). These are not the only findings that call for taking into account the epistemic function of language in the processes of knowledge constitution as a medium of thinking (Heller & Morek, 2015; Vygotsky, 1978). Students with low language proficiency might be hindered not only by reading obstacles in tests (communicative function of language); they also seem to be constrained during the whole learning-teaching process, especially with regard to topics with higher cognitive demands (Prediger, Wilhelm, Büchter, Gürsoy, & Benholz, 2018). With respect to language diverse classrooms (Barwell et al., 2016), language is increasingly treated also as a learning goal (Lampert & Cobb, 2003), and the conceptualization of academic language and everyday language (Cummins, 2000; Schleppegrell, 2004; Snow & Uccelli, 2009) is well established and discussed in mathematics education research.

Acknowledging this twofold role of language as learning medium and learning goal, research and practice in mathematics education has already put effort into enhancing students’ academic language proficiency (Barwell et al., 2016). However, most practical teaching approaches for language learners still focus on the level of vocabulary or specific grammar constructions (e.g., Department for Education and Employment (DfEE), 2000), although many researchers call for transcending the word and sentence level and for giving greater emphasis to the discourse level of academic language (Barwell, 2012; Moschkovich, 2002, 2015). Furthermore, it has been emphasized that students’ participation in discourse is especially important for developing conceptual understanding (Bailey, 2007, p. 15 for written products; Moschkovich, 2015, p. 57). The present study shows that the discourse practice of explaining in whole-class discussions is a crucial learning medium (explaining to learn); at the same time, it is an underrepresented learning goal, and classrooms should provide opportunities for learning to explain as part of language proficiency on the discourse level.

In this way, the present study aims at gaining a deeper understanding of the interplay between, rather than unidirectional impact of, academic language proficiency on the discourse level, participation in classroom discourse, and mathematics learning opportunities. Therefore, whole-class discussions are analyzed from two perspectives: The epistemic perspective focuses on the processes of joint knowledge constitution and their mathematical peculiarities and describes students’ participation in single situations but also across situations. The linguistic perspective analyzes the same processes and students in the perspective of language proficiency on the discourse level. Coordinating these perspectives provides the theoretical foundation for pursuing the following overall research question:

How is limited discourse competence connected to students’ participation in knowledge construction and how does that constrain their mathematical learning opportunities?

After a theoretical overview on discourse and practices in mathematics education, the theories of Interactional Discourse Analysis (IDA) and Interactional-Epistemic Perspective (IEP) are presented in Section 1. Section 2 outlines the methods of the study. The quantitative and qualitative results are then presented and the insights from both perspectives are coordinated in Section 3 and discussed in Section 4.

1 Theoretical background

1.1 Discourse and practices in mathematics education research

Krummheuer (2011) and Sfard (2008) gave the term participationist perspectives to all those theoretical approaches in which learning is conceptualized as participation in classroom discourses: “Whereas acquisitionists view individual development as proceeding from personal acquisitions to participation in collective activities, participationists reverse the picture and claim that people go from participation in collectively implemented activities to similar forms of doing performed single-handedly” (Sfard, 2008, p. 78). More or less explicitly, the participationist perspective follows traditions of Vygotsky (1978), where learning mathematics is conceptualized as corresponding to “a process of enculturation into mathematical practices, including discursive practices (e.g., ways of explaining, proving, or defining mathematical concepts)” (Barwell, 2014, p. 332). Prominent are references to Lave and Wenger’s (1991) construct of legitimate peripheral participation. Applied to mathematics learning in schools, students’ learning is seen as inseparable from participation in the classroom interaction.

Within the mathematics education community, the participationist perspective can be traced back to early interactionist perspectives, focusing on norms and practices and how they are interactively established in classroom micro-cultures (Cobb & Bauersfeld, 1995; Yackel & Cobb, 1996). The construct of mathematical practices was introduced to capture collective mathematical development and describes interactively established ways of joint action in mathematics classrooms. It is used descriptively and prescriptively in design research frameworks (Yackel & Cobb, 1996); prescriptive use is also dominant in curricula (e.g., Common Core State Standards Initiative, 2010). Here, it is used only for descriptive purposes.

More recently, Sfard (2008) even conceptualizes communication and cognition as inseparable in the joint term commognition. Although we share Sfard’s perspective that interaction and students’ epistemic processes (i.e., processes of individual knowledge constitution) are strongly intertwined, we prefer to analytically separate the discourse from the epistemic processes in order to be able to investigate their subtle and strong connections empirically.

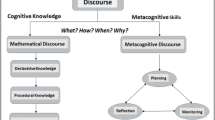

Research in the last decade has repeatedly shown that students with underprivileged social backgrounds encounter more obstacles for successful participation in classroom discourse than their peers do (Diversity in Mathematics Education Center for Learning and Teaching, 2007). The first empirical evidence from a variety of studies that this unequal participation is critical with respect to equity (e.g., Bailey, 2007; Barwell, 2012; Gresalfi, Martin, Hand, & Greeno, 2009; Krummheuer, 2011) can be combined into a hypothesized chain of connections (Fig. 1).

Participation in mathematical discourse is implicitly considered from two perspectives: taking part in discourse practices according to discursive norms (henceforth referred to as discursive participation) and taking part in the joint epistemic processes of knowledge constitution (henceforth referred to as epistemic participation). In our research approach, we disentangle both aspects and show their interplay empirically (the impact is not unidirectional, symbolized by bidirectional arrows in Fig. 1). For this purpose, a discourse analytical approach is required to conceptualize individual discourse competence as the crucial part of academic language proficiency on the discourse level (Section 1.2).

The dependencies of discursive and epistemic participation can be empirically identified in three time scales: within a given situation (“In this scene, Paul’s epistemic participation and the shown discourse competence are limited”), across several situations (“Across all analyzed situations, Paul shows similar discursive or epistemic participation profiles”, in which case we can talk about profiles), and in its development over time (“After half a year, Paul could enhance his discourse competence”).

As far as we have studied the literature, the connections between participation and learning opportunities were mainly identified within single situations (e.g., Barwell, 2012; Gresalfi et al., 2009; Krummheuer, 2011), whereas little research exists across situations or on the development over time. Thus, beyond considering written discourses (e.g., Bailey, 2007) or desirable practices (existing in curricula or in design research classrooms), we focus on analyzing oral discourses in everyday classrooms across situations and over half a year.

This research approach is theoretically grounded in the next sections by profound conceptualizations of (A) the involved aspects of academic language proficiency on the discourse level (discourse competence), and (B) constructs that capture the epistemic function of language in the epistemic processes of students’ knowledge construction.

1.2 Discourse practices and discourse competence in the Interactional Discourse Analysis (IDA)

A variety of discourse analytic approaches have been applied and further developed in mathematics education research (Ryve, 2011, for a critical overview). For example, analysis with Systemic Functional Linguistics reveals whether a student participates or not (e.g., Meaney, Trinick, & Fairhall, 2012; Setati, 2005). However, none of these approaches provides a conceptualization of individual students’ discourse competence in order to grasp the notion of participation in more detail. The perspective of Interactional Discourse Analysis (IDA; Quasthoff, Heller, & Morek, 2017) fills this gap as it matches the descriptive needs and comprises the idea of vocabulary and grammar serving discourse practices. This article shows how it substantially contributes to the process of theorizing, especially with respect to individual discourse competences.

IDA is compatible with participationist views in mathematics education, as it conceptualizes discourses as interactionally co-constructed according to the shared ethnomethodological roots (Garfinkel, 1967). In this framework, oral discourse practices are defined as multi-unit turns that are interactively co-constructed, contextualized, and functionally oriented towards particular genres (Bergmann & Luckmann, 1995) such as narration, explanation, or argumentation. Hence, discourse practices rely on patterns available in speech communities’ knowledge, for instance, to solve the communication-related problem of conveying or constructing knowledge (explanations) or negotiating divergent validity claims (argumentation). This definition particularly offers a way of differentiating different discourse practices and thus offers an opportunity for further specifying the language demands of talk in mathematics classrooms. Furthermore, it is compatible with research on argumentation and explanation in mathematics education (e.g., Krummheuer, 2011; Mercer, Wegerif, & Dawes, 1999).

Based on several empirical studies on acquisition of different discourse practices, IDA developed a model of discourse competence that is analytically divided into three facets (Quasthoff, 2011):

-

Contextualization competence is the ability to embed the discourse unit in a particular (social and sequential) context and shape it accordingly.

-

Textualization competence describes the ability to internally build up a discourse unit according to the requirement of the specific practice.

-

Marking competence captures the ability to use linguistic forms in order to explicate (con)textualization structures, thus communicating them adequately.

Accordingly, students who participate adequately in classroom discourse have to recognize contextually when to place which discourse practice (e.g., explanation instead of narratives), master the specific textualization patterns (e.g., explaining general procedures step-by-step), and use a specific lexical and grammatical repertoire to mark it (e.g., “that’s why” for explaining). A study comparing the same fifth graders’ activities in families, peer groups, and class (Morek, 2015) revealed that contextualization competence is the key competence to participate adequately in class. It strongly depends on acquisitional contexts outside school and therefore forms a source of social differences.

Whereas IDA provides the theoretical perspective for describing different discourse practices, discursive participation and individual discourse competence (Fig. 2), the Interactional-Epistemic Perspective (IEP) focuses on the joint epistemic processes of knowledge constitution and the individual profiles of epistemic participation (Erath & Prediger, 2015).

1.3 Interactional-Epistemic Perspective (IEP) on discourse practices of explaining

The IEP elaborated interactionist traditions (Section 1.1) by analyzing the joint epistemic processes of knowledge constitution systematically. In this way, it investigates which forms of knowledge (conceptual/procedural) are constituted in which epistemic modes (e.g., explicit formulations, exemplifications, or functions) and by whom in the interaction in mathematics classrooms. For this epistemic focus, Prediger and Erath (2014) developed the epistemic matrix as tool for analyzing explanations in whole-class discussions (Fig. 3) since they serve as important mathematical learning opportunities. In the matrix, each utterance in collective explanations is captured, including both questions and answers, by assigning one or more epistemic fields (cells of the matrix).

Epistemic matrix as analytic tool for epistemic processes (with the navigation pathway of Episode 1). Note: Circles with turn numbers show teachers, rectangles with names and turn numbers show students, and arrows indicate teacher’s navigations, e.g., demanding an explicit formulation after student’s offered examples

The rows of the matrix comprise categories of possible objects of explaining (indicated by “--”), differentiated in four conceptual and three procedural logical levels. For example, a teacher can ask for both an explanation of the --concept-- “maximum” and the --procedure-- of identifying it in a diagram.

In the columns of the matrix, the different means by which an object can be explained are systematized in six different epistemic modes (indicated by “||”) that categorize the role of the means for the constitution of knowledge: ||labelling & naming|| is the only mode that can be addressed by a single word (e.g., “maximum”). The more linguistically elaborate mode ||explicit formulation|| includes verbalizing formal theorems (--propositions--) and definitions (--concepts--) as well as instructions (--procedures--). The mode ||exemplification|| addresses examples and counterexamples, whereas ||meaning & connection|| comprises all aspects that bridge to another level or mode, for example, pre-existing knowledge. The mode ||purpose & evaluation|| belongs to a pragmatic approach of explaining by its inner mathematical or everyday functions, often combined with an evaluation of applicability. Going back to the aforementioned example of the --concept-- “maximum,” a student can explain it by giving a definition (||explicit formulation||) or examples (||exemplification||). By these means, utterances are characterized from a subject-specific perspective while simultaneously bearing the interactional nature of knowledge constitution in mind.

This is further reflected in the second function of the epistemic matrix: Displaying the analysis of all utterances of one collective explanation in the epistemic matrix allows the researchers to capture whole sequences in so-called explaining pathways through the matrix (Fig. 3). The interactive process can thus be visualized and an individual student’s contribution can be located not only from a mathematical perspective (in the matrix) but especially in its embedding in the process (in the pathway).

1.4 Refined research questions

Based on these theoretical foundations, we focus our analysis on a specific discourse practice: explaining in whole-class discussions in grade 5 classrooms. This choice will be justified by the results from research question Q1, as explaining turns out to be the most frequently demanded discourse practice. In order to investigate how discourse competence and the discourse practice of explaining intertwine with the learning of mathematics, we rely on the coordinated theoretical framework, span the investigation across several situations and over time (i.e., after half a year), and thereby refine the preliminary general research question into two finer questions, Q2 and Q3:

-

Q1

How frequently does explaining occur among the discourse practices established in grade 5 classrooms and how much do students actively participate in the discourse situations?

-

Q2

How can students’ discursive and epistemic participation in explanations in whole-class discussions be characterized across situations and over time?

-

Q3

To which degree do these participation profiles coincide with each other and with students’ discourse competences and how do they develop over time?

2 Methods for the quantitative and coordinated qualitative analysis of classroom interactions

Within the interdisciplinary project InterPass, two coordinated qualitative analyses of the video data were conducted in IEP and IDA, first separately, then by searching for empirical and theoretical alignment of dually conceptualized phenomena. This way of coordinating two theoretical perspectives is one of the strategies for networking theories (Prediger, Bikner-Ahsbahs, & Arzarello, 2008). The methodological prerequisite of coordinating theoretical perspectives is the coherence of background theories, which is here guaranteed by joint ethnomethodological roots underlying both interactionist approaches (Erath, 2017b; Garfinkel, 1967).

2.1 Methods for data gathering

Video data was gathered in grade 5 classes (students’ aged 10–11 years old) in five schools with different achievement levels and in neighborhoods with contrasting social backgrounds. Seventy-three mathematics lessons were filmed (55 full hours of video material): At least eight lessons in each classroom were filmed directly after students’ transition to secondary school and about four lessons in each were filmed 6 months later in order to grasp continuities and discontinuities. The study focuses on whole-class discussions, not on seatwork or group work where less support for acquiring discourse competence can be expected. About 190 sequences of whole-class discussion were transcribed. Questionnaires were administered on students’ family and language background.

The qualitative part of this article refers to three focus students from a grammar school in a non-privileged urban area. The classroom was chosen based on the quantitative analysis as the one with the highest student participation time in classroom discourse. Three boys were selected due to similar backgrounds (gender, age, father Turkish, mother German) but different kinds of participation. The data corpus for the longitudinal analysis comprises all transcripts of whole-class discussions that actively involved the boys (beginning + middle of the year: Monir 27 + 12 transcripts, Nahema 15 + 4, Thasin 34 + 14), including data from German language lesson in the case of IDA.

2.2 Methods for the quantitative video data analysis

Time analysis for students’ participation

In a first quantitative approach, students’ participation was operationalized by all students’ share of time in classroom discourse and measured by a time analysis of the video material in all classrooms. As Praetorius, Pauli, Reusser, Rakoczy, and Klieme (2014) showed that analyzing one lesson gives a sufficiently reliable measure for classroom management (providing students with quality learning time), the lesson with the greatest extent of classroom discourse (operationalized by longest duration of globally organized whole-class talk) was selected for each classroom. Based on timecodes for each speaker’s contribution, we measured lesson time, length of classroom discourse, length of globally organized parts of the classroom discourse, and length of teachers’ and students’ utterances in globally organized parts of the classroom discourse. The different shares in classroom discourse were then calculated in relation to the overall duration of classroom discourse.

Frequency analysis of discourse practices

In order to capture the complete video material with respect to the established discourse practices, teachers’ demands (i.e., questions and prompts) for different discourse practices were coded in the whole-class discussion time of all 55 h of mathematics lessons (operationalizations of the practices are given in Fig. 4). The coding was conducted by two independent raters, who reached an agreement of 90% for same codings. After the interrater reliability check, the coders discussed all divergent codes to achieve full agreement.

2.3 Methods for the qualitative data analysis

Linguistic analysis by IDA

Students’ performances in the facets of contextualization, textualization, and marking (Section 1.2) were analyzed by means of the analytic tool GLOBE (Hausendorf & Quasthoff, 2005), which captures students’ discourse participation within single situations as well as their discourse competence across situations in the whole data corpus.

Epistemic analysis by IEP

For the epistemic analysis, each explanation demanded or given in a classroom interaction was characterized by the addressed epistemic fields (Section 1.3). The epistemic participation of each student within a single discourse situation can be grasped by its location in the matrix and in relation to the joint epistemic processes of knowledge constitution that are captured by explaining pathways through the matrix (based on consensual validation of all four researchers). The focus students’ utterances were further evaluated as having high epistemic quality if two of the following categories were fulfilled (Erath, 2017b, pp. 208ff for detailed analysis): (1) the utterance was seized, (2) the utterance contributed to an advanced step in knowledge constitution (i.e., not to collecting everyday experiences), and (3) the cognitive demand of the addressed epistemic fields (i.e., not referring to pure knowledge of facts or repetition). In order to capture the profiles (Erath & Prediger, 2015) and find the regularities across situations and in its development, these evaluations were collected in the epistemic matrix (Fig. 8).

3 Empirical results

3.1 Results of the quantitative analysis: differing opportunities for explaining across classroom micro-cultures

3.1.1 Frequency analysis for discourse practices

The frequency analysis of discourse practices coded and counted all teachers’ demands for each discourse practice (Q1) and shows the relevance of explaining in the observed whole-class discussions (Fig. 4). Teacher demands were selected since (1) they are easier to identify and categorize than whole sequences, (2) they are highly relevant for students’ learning opportunities as they structure the process, and (3) teachers’ epistemic expectations influence the space of cognitive demands of students’ answers.

The five math teachers elicited discourse practices 359 times in 55 h. The most frequent practices were explaining and arguing, which mainly address the negotiation of meanings relevant for developing conceptual understanding (which cannot be accomplished by reporting or describing), but also address explaining general procedures, etc. Reporting concrete solution pathways are demanded less often. This dominance of explaining justifies the theoretically set focus on these activities from the empirical perspective also. Furthermore, with 15 occurrences, word explanations did not have the importance attributed to them in the literature on language-sensitive classrooms (e.g., DfEE, 2000).

3.1.2 Time analysis for approximating students’ participation in discourse practices

The variance between learning opportunities for discourse practices in five mathematics classrooms becomes visible in the time analysis for each class. Figure 5 shows the average percentage of time in whole-class discussions devoted to

-

whole-class talk with so-called local sequences in which students’ utterances are restricted to isolated words or maximally one sentence (not counted as discourse practices) and,

-

within the time dedicated to discourse practices (discourse units comprising more than a sentence), the share of teachers’ and students’ activities.

The share of students’ discourse activities (up to 39%) indicates that mathematics classrooms are an important place for enculturation into discourse practices, just as in language lessons, as the overall project has shown (Erath, 2018). However, the class-wise comparison shows that students’ participation in whole-class discourse activities varies, particularly between classes A and C. This huge variance shows that a large share of discourse practices (the two lower parts of the stacks together) does not necessarily mean a high amount of student participation in discourse practices, since teachers can take a lot of time.

Although the small classroom sample size (n = 5) is not suitable for statistical generalization, we can conclude that comparing only the differences between seatwork, group work, and whole-class discussion (as done, for example, in Hiebert et al., 2003) cannot account for students’ opportunities for active participation in discourse practices.

3.2 Two episodes with students’ differential participation

For the qualitative analysis within a given situation (Section 1.1) with respect to research questions Q2 and Q3, we zoom into the micro-culture of class A. Among all observed classrooms, this teacher has established the most opportunities for students’ active participation within whole-class discourse practices. Thereby, gains of the two theoretical perspectives and their interrelation can be demonstrated in order to account for the connection between epistemic and discursive participation in classroom discourse (Fig. 2), discourse competence, and differential mathematical learning opportunities. For this, three multilingual boys with different language proficiencies in German are compared: Nahema, Monir, and Thasin.

3.2.1 Episode 1: “The meaning of rounded zero”

Episode 1 is part of a whole-class discussion on the interpretation of “no symbol” for cats in the dot plot in Fig. 6. Two students gave opposing interpretations (“nothing written” versus “under ten kilograms, maybe one and a half or two”) followed by teacher’s demand to collect several weights of cats (line 14) in order to evaluate the solutions (the translated transcripts use “[…]” for missing parts, “(.)”, “(-)”, and “(--)” for breaks of increasing length, and all capital letters for emphasized words):

Interpreting a rounded zero (Esper & Schornstein 2005, p. 11; translated by the authors)

Analysis in IDA

This sequence shows very diverse ways of discursive participation that Nahema, Monir, and Thasin have within a single situation:

-

Nahema textualizes adequately; however, he does not contextualize his report as factual evidence but rather as a “sensation.” As far as this goes, his contextualization does not entirely succeed: He does not tailor it to its function within the explanation.

-

Monir contextualizes the conditional relevance adequately and textualizes his discourse unit by demonstrating a conclusion: Initially, he elaborates the premise, exemplifies it, and marks a contrast (using “but,” line 35). The conclusion is not explicated, although he begins to refer to the mathematical model. Monir’s recurrent hesitations and reformulations, his resorting to gestures and examples points to the limits of his marking competence.

-

Thasin contextualizes adequately and explicates a possible mathematization by using subjunctive and reference to a general rule. By using more complex linguistic devices such as the structure of conditions “if. . . then,” technical terms and the impersonal pronoun, he succeeds in a generalizing textualization to the point, which expresses the explanation precisely and detaches it from the particular case. Thus, his discursive participation is the most elaborate in textualization and marking.

Analysis in IEP

Altogether five children state their experiences with the weight of cats, addressing the epistemic mode ||meaning & connection|| on the logical levels --concrete solution-- and --models-- (“--” symbolizes the levels and “||” symbolizes the modes in the epistemic matrix in Fig. 3). The stated weight of cats rises up to ‘NINE kilo’ (Nahema, line 24), which is rejected by other students. In lines 28/30, the teacher navigates back to the mathematical core of the episode by asking how the situation might be modeled. In the epistemic matrix, this navigation is represented as a shift to the epistemic field --models-- ||explicit formulation|| (Fig. 3). Monir shifts to the meaning of the weight symbols (--models-- ||meaning & connection||) and then to the mode ||explicit formulation|| in line 35 by explaining that a weight symbol is not printed when the weight has less than 2 digits. The teacher does not evaluate Monir’s utterance but supports accomplishing it by translating his gestures into words. Thasin (lines 39/41) models the situation by using the concept of rounding on tens and directly addresses the epistemic field --models-- ||explicit formulation||. In his conclusion (line 42), the teacher evaluates Monir’s and Thasin’s suggestions as plausible and reformulates both.

From the IEP, Episode 1 illustrates some of the main differences in students’ epistemic participation within a single situation: Whereas Nahema contributes at the beginning of the episode by stating his everyday experience, Monir and Thasin take part in the cognitively more demanding explanations of possible mathematical models for the dot plot in later steps of the navigation pathway. Their utterances have a higher epistemic quality.

3.2.2 Episode 2: “Smart lists”

Episode 2 is extracted from a whole-class discussion on different ways of sorting students’ signs of the zodiac (which were written unsorted on the blackboard before), starting from two students’ lists on the blackboard (Fig. 7).

Analysis in IDA

Nahema offers a minimally argumentative discourse unit, positioning himself in favor of one solution. He contextualizes adequately, whereas in textualizing, he does not fulfill teacher’s expectations for giving reasons and balancing pros and cons. Nahema adequately marks his small unit. Monir’s contribution reveals a relatively high contextualizing competence in that he embeds his unit by taking up issues that have been discussed before (“easier” in line 29) and developing them further. He textualizes by relating two criteria and suggesting a concrete improvement. Monir marks his contribution by the connector “but” for the adversative relation between the two features balanced in his argument. His exemplary suggestion relies on deictic devices and gestures, which is communicatively sufficient for the visually accessible chart.

Analysis in IEP

Episode 2 exemplifies a repeatedly observed way of explaining in this classroom: In a first step, the teacher asks the class to compare the lists and state advantages and disadvantages (line 01), the teacher addresses the levels --concrete solutions/procedures/semiotic representations-- in the epistemic mode ||purpose & evaluation|| since he demands an evaluation of two representations and the procedures for their generation, which are at the same time the concrete solutions of two students. This serves as a starting point for the second step: the explication of hints and instructions for creating “good” representations (not printed here completely, only Monir’s contribution in line 29).

Students’ varying epistemic participation becomes visible here in unequally demanding steps of the collective pathways through the epistemic matrix and the linked processes of knowledge construction. Whereas Nahema participates only in the first step by evaluating the two lists by repeating a previously mentioned category (Denise, line 07) and without referring to a mathematical basis, Monir contributes to the second step, which is cognitively more demanding: Monir gives an idea for improvement, building on his evaluation; therefore, the epistemic quality of his utterance is higher.

The two episodes show that within two given situations, the discursive and epistemic participation coincide: higher degrees of discourse competence and higher epistemic quality can be observed in the same utterances. The next section presents the analyses across situations and over time.

3.3 Epistemic participation profile across situations and over time (IEP)

Both episodes presented illustrate typical characteristics of the three students’ participation in whole-class discussions as identified recurrently. The recurrent patterns are visible across situations in the identified epistemic participation profiles based on 22 analyzed transcripts (all transcripts with a mathematical contribution of one of the three students).

The three boys’ epistemic participation profiles (Fig. 8) were compiled by locating all their contributions in the addressed epistemic fields (Erath & Prediger, 2015) and by capturing the epistemic quality of their utterances (Erath, 2017b). As an example of how the contributions were coded, the entry “2.4.8” in the column “M” represents Monir’s eighth contribution in the fourth lesson of the second data collection and bold italics indicates that two of the three categories of epistemic quality (Section 2.3) were fulfilled. That the entry can be found in several fields means that Monir addressed different epistemic fields with the contribution coded “2.4.8.”

Epistemic participation profiles (from Erath & Prediger, 2015)

Clear tendencies become visible, even without accounting for the complete analysis:

-

Thasin (violet) frequently connects different logical levels and addresses the epistemic mode ||meaning & connection|| on procedural and conceptual logical levels. Most of his contributions show a high epistemic quality. Thereby, the construction of meaning of cognitively demanding content is a central characteristic of his epistemic profile.

-

Monir (blue) mainly stays on procedural levels and succeeds in contributing to developing abstract content on these levels. This is reflected in the mainly high epistemic quality of his utterances. He rather rarely contributes in classroom discourse on conceptual levels.

-

Nahema (green) also mainly addresses procedural levels but, in contrast to Monir and Thasin, the epistemic quality of his contributions is mainly low. Most of the time, he contributes by referring to purposes and sometimes first ideas concerning meaning and assessment of concrete solutions and procedures.

Most striking for us was the finding that across all sequences (Erath, 2017b), no development over time could be found for the focus students’ epistemic participation. In contrast, their addressed epistemic fields and the epistemic quality of their contributions stay rather constant. This also applies to moments in which students raise their hands without being called on.

3.4 Discursive participation profile across situations and over time (IDA)

In the IDA analysis, the two episodes presented in Section 3.2 also appear typical for students’ discursive participation profiles across situations. These discursive participation profiles have been identified by the observable indicators in all relevant sequences involving the focus boys, including transcripts from German language classes in the case of IDA.

The results are summarized in Table 1 and are based on more than the two episodes shown; thus, not every episode is represented as a single entry. They show clear coherences across situations and little development over time, the exception being Nahema, who started with rather local contributions that became increasingly discursive. Since the competences are regarded as a continuum, a description of each competence is given for each student instead of a strict classification. However, there are big differences in the three boys’ discursive participation profiles, from which we can conclude that there are underlying differential discourse competences.

3.5 Coordinating the perspectives on discursive and epistemic participation profiles

Although the participation of the three focus boys was analyzed separately in IEP and IDA, the empirical results of the discursive and epistemic participation profiles can be perfectly aligned, in both the concrete episodes (Section 3.2) and across all analyzed episodes and over time (Sections 3.3 and 3.4). The alignment of the coordinated perspectives shows not only that discourse competence is a prerequisite for productive and receptive discursive and epistemic participation but also how it is:

-

For students like Nahema who have difficulties in contextualizing academic language practices, it seems harder to step in in the epistemically relevant moments. Only in the beginning of navigation pathways, he contributes with low epistemic quality.

-

Students like Monir, who adequately contextualizes discursive practices such as explaining and arguing but predominantly employs illustrative procedures, show substantial mathematical learning opportunities. However, they are epistemically restricted to procedural levels, with a threshold to conceptual levels, which are crucial for higher cognitive demands.

-

Students like Thasin, who already dispose of more complex academic language devices and are able to independently textualize in a more abstract or general way, are also able to address different epistemic modes referring to more cognitively demanding content. With the active part they play in linking different levels and modes, they substantially contribute to conceptually deep knowledge construction.

Hence, the analysis of classroom discourse from the perspectives IDA and IEP shows how the joint epistemic processes of knowledge constitution (which constitute mathematical learning opportunities) are shaped by the discourse competence underlying the discursive participation.

4 Conclusion and discussion

Language has often been described in its duality as both learning medium and learning goal (Lampert & Cobb, 2003). In this study, we investigated the duality in depth for the discourse practice of explaining in grade 5 whole-class discussions. Our analysis shows that explaining is the most frequent discourse practice (Q1), in which students’ active participation is very heterogeneous. Further analysis shows that discourse competence plays an important role in the learning of mathematics, since the identified epistemic and discursive participation profiles coincide (Q2/Q3):

“Explaining to learn” was shown to be highly relevant, as the discursive practice of explaining was quantitatively and qualitatively identified as crucial in the joint epistemic processes of knowledge constitution. The comparison of the three boys shows that discourse competences can be an unequally distributed prerequisite and that it shaped their discursive participation profiles, as has been shown in other studies (Barwell, 2012; Meaney et al., 2012; Mercer et al., 1999; Setati, 2005). What our investigation has added is to show how this coincides with their epistemic participation profiles across situations rather than within one situation. Even without accounting for causalities, these findings enrich earlier observations, as the epistemic process of knowledge construction is in view. The coordinated networking analysis provided insights into how all three facets of discursive competence are required for productively participating, especially in cognitively demanding classroom discourses. Beyond the quantity of students’ contributions, their location in the epistemic matrix proved particularly crucial for evaluating the epistemic quality of students’ participation in the process of joint knowledge construction, which is connected to students’ repertory of textualization. These findings provide an additional empirical grounding for Moschkovich’s (2015) emphasis on academic discourse competence as a prerequisite for knowledge construction, rather than knowledge of grammar and vocabulary.

However, other articles from the same project show (Erath, 2017a, 2018) that “learning to explain” has rarely taken place: In most classrooms, the allowance of any contribution, especially in the first steps of navigation pathways, produces a superficial broad participation of all students. This article shows systematically that the cognitively demanding parts of the epistemic navigation pathways are carried by those students with high discourse competence, like Thasin. Within a large body of video data, learning opportunities for discourse competence were rare, and students like Nahema and Monir received little support in contextualizing the discursive expectations or textualizing in more general and abstract ways. These insights complement the quantitative results on limited space for student participation (Hiebert et al., 2003) and call for further research.

Theorizing and investigating the interplay between “language use and human knowing” is one of the points highlighted by Ryve (2011, p. 188) as a further direction for research on discourse in mathematics classrooms. We have contributed to further defining discourse by introducing the concept of discourse competence and have shown how the specificity of discourse in mathematics classrooms can be included in research on general classroom discussions.

In spite of methodological limitations (small sample, restricted contexts, and no causality) which constrain a broad generalization, we can conclude that the discursive practice of explaining should be a more explicit learning goal in mathematics classrooms in order to compensate for unequally distributed discursive prerequisites (as similarly shown in different context by Meaney et al., 2012). Therefore, further research is needed to develop teaching-learning arrangements and professional development, with a focus on discursive rather than only on lexical and syntactical aspects of language-responsive teaching and learning.

References

Bailey, A. (2007). The language demands of school. Putting academic English to the test. New Haven: Yale.

Barwell, R. (2012). Discursive demands and equity in second language mathematics classrooms. In B. Herbel-Eisenmann, J. Choppin, D. Wagner, & D. Pimm (Eds.), Equity in discourse for mathematics education (pp. 147–163). Dordrecht: Springer.

Barwell, R. (2014). Language background in mathematics education. In S. Lerman (Ed.), Encyclopedia of mathematics education (pp. 331–336). Dordrecht: Springer.

Barwell, R., Clarkson, P., Halai, A., Kazima, M., Moschkovich, J., Planas, N., … Ubillus, M. V. (Eds.). (2016). Mathematics education and language diversity. The 21 st ICMI study. Cham: Springer.

Bergmann, J. R., & Luckmann, T. (1995). Reconstructive genres of everyday communication. In U. Quasthoff (Ed.), Aspects of oral communication (pp. 289–304). Berlin: de Gruyter.

Cobb, P., & Bauersfeld, H. (Eds.). (1995). The emergence of mathematical meaning. Interaction in classroom cultures. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Common Core State Standards Initiative – National Governors Association Center for Best Practices, Council of Chief State School Officers. (2010). Common core state standards for mathematics. Washington: National Governors Association Center for Best Practice.

Cummins, J. (2000). Language, power and pedagogy. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Department for Education and Employment (DfEE). (2000). The national numeracy strategy. Mathematical vocabulary. London, UK: DfEE. Retrieved January 23, 2016, from http://www.belb.org.uk/Downloads/num_mathematics_vocabulary.pdf

Diversity in Mathematics Education Center for Learning and Teaching. (2007). Culture, race, power, and mathematics education. In F. Lester (Ed.), Second handbook of research on mathematics teaching and learning (pp. 405–433). Charlotte: Information Age.

Erath, K. (2017a). Implicit and explicit processes of establishing explaining practices. Ambivalent learning opportunities in classroom discourse. In T. Dooley & G. Gueudet (Eds.), Proceedings of the tenth congress of the European Society for Research in Mathematics Education (pp. 1260–1267). Dublin: DCU and ERME.

Erath K. (2017b). Mathematisch diskursive Praktiken des Erklärens [Mathematical discursive practices of explaining]. Doctoral dissertation. Wiesbaden: Springer.

Erath, K. (2018). Creating space and supporting vulnerable learners. Teachers’ options for facilitating participation in oral explanations and the corresponding epistemic processes. In R. Hunter, M. Civil, B. Herbel-Eisenmann, N. Planas, & D. Wagner (Eds.), Mathematical discourse that breaks barriers and creates space for marginalized learners (pp. 39–60). Rotterdam: Sense.

Erath, K., & Prediger, S. (2015). Diverse epistemic participation profiles in socially established explaining practices. In K. Krainer & N. Vondrová (Eds.), Proceedings of the ninth congress of the European Society for Research in Mathematics Education (pp. 1374–1381). Prague: Charles University and ERME.

Esper, N. & Schornstein, J. (Eds.). (2005). Fokus Mathematik Gymnasium Klasse 5 Nordrhein-Westfalen. Berlin: Cornelsen.

Garfinkel, H. (1967). Studies in ethnomethodology. Engelwood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Gresalfi, M. S., Martin, T., Hand, V., & Greeno, J. G. (2009). Constructing competence: An analysis of student participation in the activity systems of mathematics classrooms. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 70(1), 49–70.

Haag, N., Heppt, B., Stanat, P., Kuhl, P., & Pant, H. A. (2013). Second language learners’ performance in mathematics. Disentangling the effects of academic language features. Learning and Instruction, 28(0), 24–34.

Hausendorf, H., & Quasthoff, U. (2005). Konversations-/Diskursanalyse. (Sprach-)Entwicklung durch Interaktion [Conversation-/discourse analysis. Language development through interaction]. In G. Mey (Ed.), Qualitative Forschung in der Entwicklungspsychologie (pp. 585–618). Cologne: Kölner Studien Verlag.

Heller, V., & Morek, M. (2015). Academic discourse as situated practice. Linguistics and Education, 31, 174–186.

Hiebert, J., Gallimore, R., Garnier, H., Givvin, K. B., Hollingsworth, H., Jacobs, J., … Stigler, J. (2003). Teaching mathematics in seven countries. Results from the TIMSS 1999 video study, NCES (200–013), U.S. Department of Education. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics.

Krummheuer, G. (2011). Representation of the notion “learning-as-participation” in everyday situations of mathematics classes. ZDM Mathematics Education, 43(1/2), 81–90.

Lampert, M., & Cobb, P. (2003). Communication and learning in the mathematics classroom. In J. Kilpatrick & D. Shifter (Eds.), Research companion to the NCTM standards (pp. 237–249). Reston: NCTM.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning. Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge: University Press.

Meaney, T., Trinick, T., & Fairhall, U. (2012). Collaborating to meet language challenges in indigenous mathematics classrooms. Dordrecht: Springer.

Mercer, N., Wegerif, R., & Dawes, L. (1999). Children’s talk and the development of reasoning in the classroom. British Research Journal, 25(1), 95–111.

Morek, M. (2015). Show that you know. Explanations, interactional identities and epistemic stance-taking in family talk and peer talk. Linguistics and Education, 18(31), 238–259.

Moschkovich, J. (2002). A situated and sociocultural perspective on bilingual mathematics learners. Mathematical Thinking and Learning, 4(2&3), 189–212.

Moschkovich, J. (2015). Academic literacy in mathematics for English learners. The Journal of Mathematical Behavior, 40(A), 43–62.

Pimm, D. (1987). Speaking mathematically. Communication in mathematics classrooms. London: Routledge.

Praetorius, A.-K., Pauli, C., Reusser, K., Rakoczy, K., & Klieme, E. (2014). One lesson is all you need? Stability of instructional quality across lessons. Learning and Instruction, 24(31), 2–12.

Prediger, S., & Erath, K. (2014). Content or interaction, or both? EURASIA Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 10(4), 313–327.

Prediger, S., Bikner-Ahsbahs, A., & Arzarello, F. (2008). Networking strategies and methods for connecting theoretical approaches. ZDM Mathematics Education, 40(2), 165–178.

Prediger, S., Wilhelm, N., Büchter, A., Gürsoy, E., & Benholz, C. (2018). Language proficiency and mathematics achievement. Journal für Mathematik-Didaktik, 38(3), 1–24.

Quasthoff, U. (2011). Diskurs- und Textfähigkeiten [Discourse and text proficiencies]. In L. Hoffmann, K. Leimbrink, & U. Quasthoff (Eds.), Die Matrix der menschlichen Entwicklung (pp. 210–251). Berlin: de Gruyter.

Quasthoff, U., Heller, V., & Morek, M. (2017). On the sequential organization and genre-orientation of discourse units in interaction. Discourse Studies, 19(1), 84–110.

Ryve, A. (2011). Discourse research in mathematics education: a critical evaluation of 108 journal articles. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 42(2), 167–199.

Schleppegrell, M. J. (2004). The language of schooling. A functional linguistics perspective. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Setati, M. (2005). Teaching mathematics in a primary multilingual classroom. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 36(5), 447–466.

Sfard, A. (2008). Thinking as communicating. Cambridge: University Press.

Snow, C. E., & Uccelli, P. (2009). The challenge of academic language. In D. R. Olson & N. Torrance (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of literacy (pp. 112–133). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Yackel, E., & Cobb, P. (1996). Sociomathematical norms, argumentation, and autonomy in mathematics. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 27(4), 458–477.

Acknowledgments

The research project InterPass (Interactive procedures of establishing matches and divergences for linguistic and microcultural practices) was funded by the German National Ministry for Education and Research (2012-2016, BMBF-grant 01JC1112 to S. Prediger/U. Quasthoff). The authors thank Anna-Marietha Vogler for her collaboration in the project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Erath, K., Prediger, S., Quasthoff, U. et al. Discourse competence as important part of academic language proficiency in mathematics classrooms: the case of explaining to learn and learning to explain. Educ Stud Math 99, 161–179 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10649-018-9830-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10649-018-9830-7