Abstract

We study the retirement effects on mental health using a fuzzy regression discontinuity design based on the eligibility age to the state pension in the Netherlands. We find that the mental effects are heterogeneous by gender and marital status. Retirement of partnered men positively affects mental health of both themselves and their partners. Partnered female retirement has hardly any effect on their own mental health or the mental health of their partners. Single persons retirement does not seem to have an effect on their mental health status.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Some studies focus on the effects of retirement on physical health or health behaviors. See for example Nielsen (2019) and Celidoni and Rebba (2017). There are also studies that investigate the effects of retirement on a composite indicator of health that includes mental health. These are also discussed below.

Quite a few studies investigate the relationship between retirement and mortality. These studies are all based on administrative data. The results are all over the place. Hernaes et al. (2013) find that a retirement reform in Norway induced some workers to indeed retire early, but their mortality was not affected. Hallberg et al. (2015) find that a retirement reform for Swedish army personnel increased early retirement and reduced mortality. Bloemen et al. (2017) using a temporary change in the rules for early retirement of older civil servants in the Netherlands finds that early retirement reduces mortality. Fitzpatrick and Moore (2018) on the other hand find that early retirement in the U.S. increased male mortality but for females there is no significant increase in mortality after retirement. Kuhn et al. (2018) use Austrian administrative data finding that retirement increased mortality for men but not for women.

For adults, the net monthly minimum wage in the Netherlands in 2018 was €1440.

They take value 0 when individual i (or his/her partner) is interviewed in the month in which (s)he becomes eligible to the state pension.

Instead of collapsing the information on mental health from ordered categories to dummy indicators, we could have used these categories either in nonlinear ordered response models or, after assigning them a cardinal meaning, in usual linear models estimated by 2SLS. However, Bond and Lang (2019) criticized the use of ordered variables like happiness scores, because it is difficult to compare these variables across individuals. By collapsing them to binary indicators, we avoid this limit.

See https://www.dataarchive.lissdata.nl/study_units/view/1 for the full list of studies of the LISS panel.

Hetschko et al. (2013) show that even though unemployed are not actively performing paid work, they do experience an increase in their life satisfaction upon retirement as social norms no longer require them to be employed whereas prior to retirement they were expected to look for a job.

Hours of work are defined as usual weekly working hours.

Since not all the respondents to the health survey responded in the same month also to the monthly background variables, we could not match 1101 observations.

The Cronbach’s alpha of these five variables suggests relatively high internal consistency. It is equal to 0.836 (0.850) for (wo)men living in a couple and 0.869 (0.857) for (fe)male singles.

References

Abolhassani, M., & Alessie, R. (2013). Subjective well-being around retirement. De Economist, 161, 349–366.

Atalay, K., Barrett, G. F., & Staneva, A. (2019). The effect of retirement on elderly cognitive functioning. Journal of Health Economics, 66, 37–53.

Barreca, A. I., Lindo, J. M., & Waddell, G. R. (2016). Heaping-induced bias in regression-discontinuity designs. Economic Inquiry, 54(1), 268–293.

Bassanini, A., & Caroli, E. (2015). Is work bad for health? The role of constraint versus choice. Annals of Economics and Statistics, 119(120), 13–37.

Belloni, M., Meschi, E., & Pasini, G. (2016). The effect on mental health of retiring during the economic crisis. Health Economics, 25(S2), 126–140.

Bertoni, M., & Brunello, G. (2017). Pappa ante portas: The effect of the husband’s retirement on the wife’s mental health in Japan. Social Science & Medicine, 175, 135–142.

Berwick, D., Murphy, J., Goldman, P., Ware, J., Barsky, A., & Weinstein, M. (1991). Performance of a five-item mental health screening test. Medical Care, 29(2), 169–176.

Bloemen, H., Hochguertel, S., & Zweerink, J. (2017). The causal effect of retirement on mortality: Evidence from targeted incentives to retire early. Health Economics, 26(12), e204–e218.

Bloemen, H., Hochguertel, S., & Zweerink, J. (2019). The effect of incentive-induced retirement on spousal retirement rates: Evidence from a natural experiment. Economic Inquiry, 57(12), 910–930.

Bond, T. N., & Lang, K. (2019). The sad truth about happiness scales. Journal of Political Economy, 127(4), 1629–1640.

Bonsang, E., Adam, S., & Perelman, S. (2012). Does retirement affect cognitive functioning? Journal of Health Economics, 31(3), 490–501.

Bonsang, E., & Klein, T. (2012). Retirement and subjective well-being. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 83(3), 311–329.

Calonico, S., Cattaneo, M., & Titiunik, R. (2014). Robust nonparametric confidence intervals for regression-discontinuity designs. Econometrica, 82(6), 2295–2326.

Cattaneo, M., Jansson, M., & Ma, X. (2018). Manipulation testing based on density discontinuity. Stata Journal, 18(1), 234–261.

Celidoni, M., Dal Bianco, C., & Weber, G. (2017). Retirement and cognitive decline. A longitudinal analysis using SHARE data. Journal of Health Economics, 56, 113–125.

Celidoni, M., & Rebba, V. (2017). Healthier lifestyles after retirement in Europe? Evidence from SHARE. European Journal of Health Economics, 18, 805–830.

Coe, N. B., & Zamarro, G. (2011). Retirement effects on health in Europe. Journal of Health Economics, 30, 77–86.

Coile, C. C. (2015). Economic determinants of workers’ retirement decisions. Journal of Economic Surveys, 29(4), 830–853.

Dong, Y. (2015). Regression discontinuity applications with rounding errors in the running variable. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 30(3), 422–446.

Eibich, P. (2015). Understanding the effect of retirement on health: Mechanisms and heterogeneity. Journal of Health Economics, 43, 1–12.

Fé, E., & Hollingsworth, B. (2016). Short- and long-run estimates of the local effects of retirement on health. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series A, 179(4), 1051–1067.

Fitzpatrick, M., & Moore, T. (2018). The mortality effects of retirement: Evidence from social security eligibility at age 62. Journal of Public Economcis, 157, 121–137.

Fonseca, R., Kapteyn, A., Lee, J., Zamarro, G., & Feeney, K. (2014). A longitudinal study of well-being of older Europeans: Does retirement matter? Journal of Population Ageing, 7(1), 21–41.

Gelman, A., & Imbens, G. (2019). Why high-order polynomials should not be used in regression discontinuity designs. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, 37(3), 447–456.

Gorry, A., Gorry, D., & Slavov, S. N. (2018). Does retirement improve health and life satisfaction? Health Economics, 27(12), 2067–2086.

Hahn, J., Todd, P., & van der Klaauw, W. (2001). Identification and estimation of treatment effects with a regression-discontinuity design. Econometrica, 69(1), 201–09.

Hallberg, D., Johansson, P., & Josephson, M. (2015). Is an early retirement offer good for your health? Quasi-experimental evidence from the army. Journal of Health Economics, 44, 274–285.

Heller-Sahlgren, G. (2017). Retirement blues. Journal of Health Economics, 54, 66–78.

Hernaes, E., Markussen, S., Piggott, J., & Vestad, O. L. (2013). Does retirement age impact mortality? Journal of Health Economics, 32(3), 586–598.

Hessel, P. (2016). Does retirement (really) lead to worse health among European men and women across all educational levels? Social Science & Medicine, 151, 19–26.

Hetschko, C., Knabe, A., & Schöb, R. (2013). Changing identity: Retiring from unemployment. Economic Journal, 124, 149–166.

Horner, E. M. (2014). Subjective well-being and retirement: Analysis and policy recommendations. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15(1), 125–144.

Imbens, G., & Kalyanaraman, K. (2012). Optimal bandwidth choice for the regression discontinuity estimator. Review of Economic Studies, 79(3), 933–959.

Johnston, D. W., & Lee, W.-S. (2009). Retiring to a good life? The short-term effects of retirement on health. Economics Letters, 103, 8–11.

Kesavayuth, D., Rosenman, R. E., & Zikos, V. (2016). Retirement, personality, and well-being. Economic Inquiry, 54(2), 733–750.

Knoef, M., & de Vos, K., (2009). The representativeness of LISS, an online probability panel. CentERdata, Tilburg University. Retrieved on 26 June 2020 from https://www.lissdata.nl/sites/default/files/bestanden/paper_knoef_devos_website.pdf.

Kolodziej, I. W., & García-Gómez, P. (2019). Saved by retirement: Beyond the mean effect on mental health. Social Science & Medicine, 225, 85–97.

Kuhn, A., Staubli, S., Wuellrich, J.-P., & Zweimüller, J. (2018). Fatal attraction? Extended unemployment benefits, labor force exits, and mortality. NBER Working Paper No. 25124, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Lee, D., & Lemieux, T. (2010). Regression discontinuity designs in economics. Journal of Economic Literature, 48(2), 281–355.

Lee, D. S., & Card, D. (2008). Regression discontinuity inference with specification error. Journal of Econometrics, 142(2), 655–674.

Mazzonna, F., & Peracchi, F. (2017). Unhealty retirement. Journal of Human Resources, 52(1), 128–151.

McCrary, J. (2008). Manipulation of the running variable in the regression discontinuity design: A density test. Journal of Econometrics, 142(2), 698–714.

Messe, P.-J., & Wolff, F.-C. (2019). The short-term effects of retirement on health with couples: Evidence from France. Social Science & Medicine, 221, 27–39.

Müller, T., & Shaikh, M. (2018). Your retirement and my health behavior: Evidence on retirement externalities from a fuzzy regression discontinuity design. Journal of Health Economics, 57, 45–59.

Nielsen, N. F. (2019). Sick of retirement? Journal of Health Economics, 65, 133–152.

Nishimura, Y., Oikawa, M., & Motegie, H. (2018). What explains the difference in the effect of retirement on health? Evidence from global aging data. Journal of Economic Surveys, 32(3), 792–847.

Rohwedder, S., & Willis, R. J. (2010). Mental retirement. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 24(1), 119–138.

Roodman, D. (2011). Estimating fully observed recursive mixed-process models with cmp. Stata Journal, 11(2), 159–206.

Scherpenzeel, A. (2010). How to cover the general population by internet interviewing: Problems of coverage and selection and possible solutions. Alert! Magazine, 50(3), 22–24.

Scherpenzeel, A. (2011). Data collection in a probability based internet panel: How the LISS panel was built and how it can be used. Bulletin of Sociological Methodology, 109(1), 56–61.

Scherpenzeel, A., & Das, M. (2010). “True” longitudinal and probability-based internet panels: Evidence from the Netherlands. In M. Das, M. Ester, & L. Kaczmirek (Eds.), Social and behavioral research and the internet: Advances in applied methods and research strategies, Chapter4 (pp. 77–104). Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis.

Van der Heide, I., van Rijn, R., Robroek, S., Burdorf, A., & Propper, K. (2013). Is retirement good for your health? A systematic review of longitudinal studies. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 1180.

Van der Klaauw, W. (2002). Estimating the effect of financial aid offers on college enrollment: A regression-discontinuity approach. International Economic Review, 43(4), 1249–1287.

van Ours, J. C. (2019). Health economics of the workplace: Workplace accidents and effects of job loss and retirement. In Oxford encyclopedia of health economics. Oxford University Press.

Xu, K. L. (2017). Regression discontinuity with categorical outcomes. Journal of Econometrics, 201(1), 1–18.

Acknowledgements

We thank CentERdata of Tilburg University for providing us with the LISS (Longitudinal Internet Studies for the Social sciences) panel data on which we based our empirical analysis. The LISS panel data were collected by CentERdata through its MESS project funded by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research. We also thank Isabella Giorgetti and participants at the 33rd Italian Association of Labour Economics (AIEL) conference (Ancona, 2018), the 59th Italian Economic Association (SIE) conference (Bologna, 2018) and seminar participants at the University of Bath, Monash University (Melbourne), LISER (Luxembourg), Deakin University (Melbourne), University of Technology Sydney and Erasmus School of Economics (Rotterdam) for helpful comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Details on Our Data and Sample

1.1 Sample Selection

Between 5072 and 6698 individuals were interviewed each year for the core study on health from 2007 until 2018, resulting in a total of 63,603 records. We matched each record on the basis of the information on the year and month of interview to the corresponding information about the retirement status and age in months coming from the background variables. We were able to match 62,502 records, belonging to 12,958 different individuals.Footnote 12 Given the aim of this paper, we restricted the sample to individuals close to the moment of the state pension eligibility. After defining according to the rules outlined in Sect. 2 a variable that measures the distance in months from the month in which an individual becomes eligible to the state pension, we kept all the observations who were within 84 months away from the month of the state pension eligibility at the moment of the interview. The sample size shrank therefore to 16,551 observations. Since the aim is, not only to unveil the effect of retirement on his/her-own mental health, but also to identify the impact on partner’s outcome variables, we restricted the sample to couples in which both partners answered the questionnaire on health (3497 couples) and to singles (4339 observations).

Finally, we dropped from the samples 128 couples for which at least one partner is interviewed in the month in which the eligibility to the state pension was attained, or in the previous or in the subsequent month. Similarly, we eliminated 79 singles. This refinement is due to a kind of heaping problem (Barreca et al. 2016) or rounding error (Dong 2015). From 1 January 2012, the state pension eligibility is indeed received from the day in which one satisfies the age requirement. Since we do not have the day of birth, but only the month in which an individual becomes eligible to the state pension, we cannot be sure, for those interviewed in the month in which they become eligible to the state pension, whether they are already eligible at the moment of the interview or they will be soon eligible to the state pension. Although this kind of error is likely to be randomly distributed across those observations interviewed in the month of state pension eligibility, it is present only above the cutoff (Lee and Card 2008). Given the small number of such observations, omitting them from the sample is the easiest way of facing the problem and getting unbiased estimates of the treatment effect for all the others (Barreca et al. 2016). The remaining sample has 3369 records of couples and 4260 singles.

Along the paper, we use different subsamples, depending on the chosen bandwidth. For example, when the chosen bandwidth is 42 (for couples satisfied by both partners), the sample is made up of 1250 couples and 2120 singles (861 men and 1259 women).

1.2 Definition of Variables and Descriptive Statistics

Table 5 clarifies the discrete nature of the outcome variables and the meaning attached to the numeric values. Information on happiness, calmness, depression, anxiety and feeling down in the last month is collected by asking individuals whether in the last month they felt, respectively, “happy”, “calm and peaceful”, “depressed and gloomy”, “very anxious” and “so down that nothing could cheer me up”. They could choose one the following six: (1) never, (2) seldom, (3) sometimes, (4) often, (5) mostly and (6) continuously. Since the top or the bottom categories were sometimes indicated rarely by respondents, we had to group them as detailed in the last column of Table 5. These five variables measuring mental health, with their original scores from 1 to 6, are the ones used to build the MHI-5 scale.Footnote 13 We summed up the scores of the five mental health variables after reversing depression, anxiety and feeling down, subtracted 5 and multiplied by 4. By doing so, the resulting MHI-5 scale spans from 100, for those reporting all 6s, to 0, for those reporting all 1 s. Larger numbers represent therefore better mental health conditions.

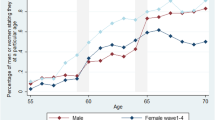

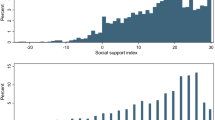

Table 6 provides descriptive statistics of the outcome variables. Table 7 reports summary statistics of the retirement indicator, the number of months from the age of state pension eligibility and the other control variables used in the econometric analysis. Finally, Fig. 4 shows the distribution of the age difference between husbands and wives in the sample used for our baseline estimates. The age difference is predominantly positive: males are on average older than their female partners. In almost 77% of the couples the male is older than the female. For 30% of the couples the male is at least two years older.

Appendix 2: Validity and Falsification Tests

As suggested by McCrary (2008), a jump in the density of the running variable at the threshold would be direct evidence of the failure of the local randomization assumption. Figure 5 displays the local polynomial density estimate of the running variable described in Cattaneo et al. (2018). The graphs show that there is no evidence of discontinuity in the population density at the cutoff, for both genders and whether living in a couple or not.

Graphical density test of the running variable, Notes: The solid line is the the local polynomial density estimate of the running variable described in Cattaneo et al. (2018). The local polynomial is of order 3. The robust bias-corrected test proposed in Cattaneo et al. (2018) cannot reject the null hypothesis of the absence of discontinuity: p value equal to 0.711 (0.293) for men (women) for couples; p value equal to 0.161 (0.872) for men (women) for singles

If the retirement probability is locally randomized near the cutoff, then the treatment should not have an effect on the pre-treatment covariates, i.e. the treated units should be similar to control units in terms of observed characteristics. We follow Lee and Lemieux (2010) and test if the discontinuity influences our predetermined variables, by estimating a seemingly unrelated regression (SUR) with one equation for each of the predetermined variables, with the same bandwidth (42 months) and local polynomial regression as in the baseline estimates. After the estimation of the SUR model, we performed joint and individual tests of the significance of the discontinuities. They are reported in Table 8. The single tests do not show systematic jumps at the cutoff: only 2 discontinuities out of 39 are significantly different from 0 at the usual 5% confidence level. All the joint tests do not reject the null hypothesis. Since we are testing the presence of discontinuities for many covariates, the joint tests suggest that the two significant discontinuities are so by random chance (Lee and Lemieux 2010).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Picchio, M., Ours, J.C. Mental Health Effects of Retirement. De Economist 168, 419–452 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10645-020-09369-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10645-020-09369-8