Abstract

Many forest protected areas (PAs) are located in developing countries, where forests are a major source of food and fuel. Thus, biodiversity conservation may have unintended consequences on welfare of people in local communities. To explore this issue, we examine the effects of the new PAs in Nepal established during 1995–2003. Using the Nepal Living Standard Survey collected in 1995/1996 and 2003/2004, we evaluate the effects of these new PAs on household consumption, wood collection, and time use. Our estimates suggest that the establishment of PAs reduce the average wood collection by 20–40% compared to the period prior to PA establishment, with greater impact when PAs are strictly managed. We find evidence that households adjust to the new PAs with at least modest shifts to fuel purchased in market but not by using fuel conserving stoves, and that PAs are ineffective when climate makes fuelwood for heating essential or if households are in regions with large dependence on wood as a fuel. Finally, while wood collection reductions could lower household welfare, we find no evidence that PAs trigger either large decreases or increases in total consumption or consumption of food.

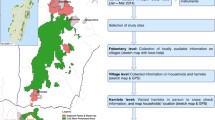

Source of shape file: World Database of Protected Area, Available at: www.protectedplanet.net. (Color figure online)

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See also http://www.protectedplanet.net/.

According to the World Bank Open Data development indicators (2018) on the terrestrial protected areas, higher income countries have 15.1% of land under protection, and lower income countries have 15.9% area under protection.

Data extracted from the Nepalese census available in IPUMS. The closest substitute for firewood is dung (11.95% in 2001 and 12.55% in 2011).

Category I includes strict nature reserves and wilderness areas, Category II includes national parks, Category III includes natural monuments and natural landmarks, Category IV includes wildlife reserves and wildlife sanctuaries, Category V includes protected landscapes/seascapes, and Category VI includes managed resource protected areas.

We also hypothesized that treatment effects might be higher if households had extensive access to livestock (since dung is a common substitute for wood as a fuel) and in places with many community forests before the PA was established so they had access to an alternative. No results supported those hypotheses, so the analyses are not reported here to reduce tables.

Only 30 households in this panel live near strict PAs, which prevents us from estimating Eq. (2).

References

Adams WM, Aveling R, Brockington D, Dickson B, Elliott J, Hutton J, Roe D, Vira B, Wolmer W (2004) Biodiversity conservation and the eradication of poverty. Science 306(5699):1146–1149

Albers HJ, Robinson EJ (2007) Spatial-temporal aspects of cost-benefit analysis for park management: an example from Khao Yai National Park, Thailand. J For Econ 13(2–3):129–150

Albers HJ, Robinson EJ (2015) 11. Spatial economics of forest conservation. In: Layton DF (ed) Handbook on the economics of natural resources. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, pp 305–329

Alix-Garcia J, Aronson G, Radeloff V, Ramirez-Reyes C, Shapiro E, Sims K, Yañez-Pagans, P (2014) Environmental and socioeconomic impacts of Mexico’s payments for ecosystem services program. International Initiative for Impact Evaluation Working paper

Allcott H (2015) Site selection bias in program evaluation. Q J Econ 130(3):1117–1165

Allendorf TD (2007) Residents’ attitudes toward three protected areas in southwestern Nepal. Biodivers Conserv 16(7):2087

Andam KS, Ferraro PJ, Pfaff A, Sanchez-Azofeifa GA, Robalino JA (2008) Measuring the effectiveness of protected area networks in reducing deforestation. Proc Natl Acad Sci 105(42):16089–16094

Andam KS, Ferraro PJ, Sims KR, Healy A, Holland MB (2010) Protected areas reduced poverty in Costa Rica and Thailand. Proc Natl Acad Sci 107(22):9996–10001

Angrist JD, Pischke J-S (2014) Mastering ‘metrics: the path from cause to effect. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Bajracharya SB (2004) Community involvement in conservation: an assessment of impacts and implications in the Annapurna Conservation Area, Nepal. Doctoral dissertation, University of Edinburgh

Baland J, Bardhan P, Das S, Mookherjee D, Sarkar R (2010) The environmental impact of poverty: evidence from firewood collection in rural Nepal. Econ Dev Cult Change 59(1):23–61

Bardhan P, Udry C (1999) Development microeconomics. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Barrett CB, Travis AJ, Dasgupta P (2011) On biodiversity conservation and poverty traps. Proc Natl Acad Sci 108(34):13907–13912

Baylis K, Honey-Rosés J, Börner J, Corbera E, Ezzine-de-Blas D, Ferraro PJ, Lapeyre R, Persson UM, Pfaff A, Wunder S (2016) Mainstreaming impact evaluation in nature conservation. Conserv Lett 9(1):58–64

Bode M, Tulloch AI, Mills M, Venter O, Ando AW (2015) A conservation planning approach to mitigate the impacts of leakage from protected area networks. Conserv Biol 29(3):765–774

Bookbinder MP, Dinerstein E, Rijal A, Cauley H, Rajouria A (1998) Ecotourism’s support of biodiversity conservation. Conserv Biol 12(6):1399–1404

Brandon K, Redford KH, Sanderson S (eds) (1998) Parks in peril: people, politics, and protected areas. Island Press, Washington

Budhathoki P (2004) Linking communities with conservation in developing countries: buffer zone management initiatives in Nepal. Oryx 38(3):334–341

Canavire-Bacarreza G, Hanauer MM (2013) Estimating the impacts of Bolivia’s protected areas on poverty. World Dev 41:265–285

CBS (1996, 2004) Nepal Living Standard Survey, Kathmandu. Retrieved from: http://cbs.gov.np

Cernea MM, Schmidt-Soltau K (2006) Poverty risks and national parks: policy issues in conservation and resettlement. World Dev 34(10):1808–1830

Clements T, Suon S, Wilkie DS, Milner-Gulland EJ (2014) Impacts of protected areas on local livelihoods in Cambodia. World Dev 64:S125–S134

Ferraro PJ, Hanauer MM (2011) Protecting ecosystems and alleviating poverty with parks and reserves:‘win-win’or tradeoffs? Environ Resour Econ 48(2):269–286

Ferraro PJ, Pattanayak SK (2006) Money for nothing? A call for empirical evaluation of biodiversity conservation investments. PLoS Biol 4(4):e105

Foerster S, Wilkie DS, Morelli GA, Demmer J, Starkey M, Telfer P, Steil M (2011) Human livelihoods and protected areas in Gabon: a cross-sectional comparison of welfare and consumption patterns. Oryx 45(3):347–356

Hansen MC, Potapov PV, Moore R, Hancher M, Turubanova SA, Tyukavina A, Thau D, Stehman SV, Goetz SJ, Loveland TR, Kommareddy A (2013) High-resolution global maps of 21st-century forest cover change. Science 342(6160):850–853

Heinen JT, Shrestha SK (2006) Evolving policies for conservation: an historical profile of the protected area system of Nepal. J Environ Plan Manag 49(1):41–58

Imbens GW, Wooldridge JM (2009) Recent developments in the Econometrics of program evaluation. J Econ Lit 47(1):5–86

Keiter RB (2014) Nepal’s buffer zone legislation: legal and policy issues

Man, U. N. E. S. C. O (2011) World Database on Protected Areas WDPA

Meyer BD (1995) Natural and quasi-experiments in economics. J Bus Econ Stat 13(2):151–161

Ministry of Culture, Tourism and Civil Aviation (2014) Tourism statistics 2013. Kathmandu, Nepal. Retrieved from http://www.tourism.gov.np/en

Miranda JJ, Corral L, Blackman A, Asner G, Lima E (2016) Effects of protected areas on forest cover change and local communities: evidence from the Peruvian Amazon. World Dev 78:288–307

Miteva DA, Pattanayak SK, Ferraro PJ (2012) Evaluation of biodiversity policy instruments: what works and what doesn’t? Oxf Rev Econ Policy 28(1):69–92

Nagendra H, Karmacharya M, Karna B (2005) Evaluating forest management in Nepal: views across space and time. Ecol Soc 10(1):24

Nelson A, Chomitz KM (2011) Effectiveness of strict vs. multiple use protected areas in reducing tropical forest fires: a global analysis using matching methods. PLoS ONE 6(8):e22722

Ostrom E (2008) Institutions and the environment. Econ Affairs 28(3):24–31

Pattanayak S, Sills E, Mehta A, Kramer R (2003) Local uses of parks: uncovering patterns of household production from the forests of Siberut, Indonesia. Conserv Soc 1(2):209–222

Paudel NS, Vedeld PO (2015) Prospects and challenges of tenure and forest governance reform in the context of REDD + initiatives in Nepal. For Policy Econ 52:1–8

Pfaff A, Robalino J, Lima E, Sandoval C, Herrera LD (2014) Governance, location and avoided deforestation from protected areas: greater restrictions can have lower impact, due to differences in location. World Dev 55:7–20

Phillips A (2004) The history of the international system of protected area management categories. Parks 14(3):4–14

Pullin AS, Bangpan M, Dalrymple S, Dickson K, Haddaway NR, Healey JR, Hauari H, Hockley N, Jones JP, Knight T, Vigurs C (2013) Human well-being impacts of terrestrial protected areas. Environ Evid 2(1):19

Rosenbaum PR (1987) The role of a second control group in an observational study. Stat Sci 2(3):292–306

Shah P, Baylis K (2015) Evaluating heterogeneous conservation effects of forest protection in Indonesia. PLoS ONE 10(6):e0124872

Sims KR (2010) Conservation and development: evidence from Thai protected areas. J Environ Econ Manag 60(2):94–114

Solon G, Haider SJ, Wooldridge JM (2015) What are we weighting for? J Hum Resour 50(2):301–316

Soussan J, Shrestha BK, Uprety LP (1995) The social dynamics of deforestation: a case study from Nepal. Parthenon Publishing Group, Nashville

The World Bank (2018) Terrestrial Protected Areas (% of total land area). Data retrieved from World Development Indicators. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/ER.LND.PTLD.ZS/?end=2018&start=2016&view=chart

Wilkie DS, Morelli GA, Demmer J, Starkey M, Telfer P, Steil M (2006) Parks and people: assessing the human welfare effects of establishing protected areas for biodiversity conservation. Conserv Biol 20(1):247–249

Yergeau ME, Boccanfuso D, Goyette J (2017) Linking conservation and welfare: a theoretical model with application to Nepal. J Environ Econ Manag 85:95–109

Acknowledgements

We thank Erica Myers, Kathy Baylis, Carl Nelson, Payal Shah, Phillip Garcia, Hope Michelson, and Xian Fan Bak for their invaluable comments and suggestions. This paper has also benefited from comments by seminar and conference participants at the Agricultural and Applied Economics Association Meeting, Association of Environmental and Resource Economics Meeting, and Southern Economics Association Annual Meeting. We would like to thank Chet Bahadur Roka from Central Bureau of Statistics of Nepal for making the NLSS data available to us. All errors are our own. This work was supported in part by USDA-NIFA Multistate Hatch W4133 Grant #ILLU-470-353 and NSF Grant #1339944.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

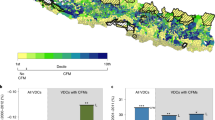

See Figs. 6, 7, 8 and Tables 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Howlader, A., Ando, A.W. Consequences of Protected Areas for Household Forest Extraction, Time Use, and Consumption: Evidence from Nepal. Environ Resource Econ 75, 769–808 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-020-00407-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-020-00407-2