Abstract

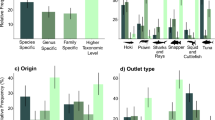

We investigate whether consumers are willing to pay for sustainability in seafood. To do this, we estimate a logit random utility model (RUM) of seafood purchases using a product-level scanner dataset from a quasi-experimental setting that includes data both before and after the implementation of a seafood advisory and sustainability label. Each seafood product is defined as a bundle of attributes, including price, species, and sustainability rating. The sustainability rating is communicated to consumers through the use of a color-based traffic light label system, where a color rating is assigned to each seafood stock-keeping unit. Combining a structural demand model with a difference-in-differences approach allows us to take advantage of the implementation of the labeling treatment in a subset of stores in the local retail chain to estimate consumers’ willingness to pay (WTP) for green, yellow, and red sustainability labels. We find that the addition of a yellow sustainability label negatively impacts consumer’s WTP for seafood products, however this simple average effect does not fully capture many independent underlying mechanisms, such as consumer preferences for wild-caught versus farmed products, and the color-distribution of available labeled products within a species, which are empirically explored. Additional results from a second stage generalized least squares regression of RUM product fixed effects on product characteristics indicate that consumers prefer selective harvest methods, wild caught seafood, and U.S. caught seafood.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

One has to look outside the seafood industry for additional empirically based studies on the efficacy of product labels. Studies on restaurants hygiene (Jin and Leslie 2003), organic milk certification (Kiesel and Villas-Boas 2007; Batte et al. 2007), wine quality (Hilger et al. 2011) and apparel (Nimon and Beghin 1999) estimate significant relationships between attributes covered by these labels and price premiums or market share gains.

As shown in a variety of settings, consumers do not always incorporate all available information (Ippolito and Mathios 1995; Mathios 2000). Teisl et al. (2002) is one of the few studies on the seafood industry using consumer purchase data to confirm that the dolphin-safe tuna label increased the market share of canned tuna. More recently, Shimshack et al. (2007) and Teisl et al. (2011), investigate the impact of seafood risk advisories for certain population groups.

Subsequent to our data collection, the yellow label’s definition was changed from “proceed with caution” to “good alternative.” We discuss this re-definition in our results and conclusion Sects. 5 and 6, respectively. Perhaps most importantly, we note that some consumers may have interpreted “proceed with caution” as a signal of increased health risk, rather than a signal about environmental sustainability.

FishWise is a sustainable seafood consultancy that promotes the health and recovery of ocean ecosystems through environmentally responsible practices. FishWise scores are assigned based on the Monterey Bay Aquarium methodology while taking into account additional third-party standards from organizations including the Marine Stewardship Council, the Aquaculture Stewardship Council, the Environmental Defense Fund, and various government agencies.

These data were previously analyzed in a reduced-form analysis by Hallstein and Villas-Boas (2013).

The data do not contain customer information.

We assume that the sustainability label system weakly increased consumers’ knowledge (information) about the environmental sustainability and healthiness of the available seafood products. Other possible sources of information include popular media, other sustainability labeling programs, and scientific literature. For example, starting in 1999, the Monterey Bay Aquarium's Seafood Watch program began distributing pocket guides about seafood sustainability to consumers. Beyond the labeling program, which is the focus of this study, we do not have information about the utilization or provision of additional information by consumers shopping at the Retailer.

Figures A1 and A2 in the Appendix present the share of seafood sales and units of seafood sold over time for all seafood products and stratified by green, yellow, and red ratings.

We define the following to be selective catch methods: midwater trawl, hand line, pole, troll, setline, bottom longline, traps, and salmon gear (Seafoodwatch 2014).

Recall that the descriptions for green labels (“best choice”) and red labels (“worst choice”) were much clearer in comparison.

We hypothesize that consumers may interpret full-price seafood as of higher quality than discounted seafood.

We estimate single-species regressions for other species as well. In all other cases, our results show no negative and significant impact on yellow labeled products.

References

Alfnes F, Guttormensen AG, Steine G, Kolstad K (2006) Consumer’s willingness to pay for the color of salmon: a choice experiment with real economic incentives. Am J Agric Econ 88:1050–1061

Asche F, Guillen J (2012) The importance of fishing method, gear and origin: the Spanish hake market. Mar Policy 36:365–369

Asche F, Larsen TA, Smith MD, Sogn-Grundvåg G, Young JA (2015) Pricing of eco-labels with retailer heterogeneity. Food Policy 53:82–93

Batte MT, Hooker NH, Haab TC, Beaverson J (2007) Putting their money where their mouths are: consumer willingness to pay for multi-ingredient, processed organic food products. Food Policy 32:145–149

Berry S (1994) Estimating discrete-choice models of product differentiation. RAND J Econ 25–2:242–262

Berry S, Levinsohn J, Pakes A (1995) Automobile prices in market equilibrium. Econometrica 63:841–890

Bjørner TB, Hansen LG, Russell CS (2004) Environmental labeling and consumers’ choice—an empirical analysis of the effect of the Nordic Swan. J Environ Econ Manag 47–3:411–434

Blomquist J, Bartolino V, Waldo S (2015) Price premiums for providing eco-labelled seafood: evidence from MSC-certified cod in Sweden. J Agric Econ. https://doi.org/10.1111/1477-9552.12106

Carroll M, Anderson J, Martinez-Garmendia J (2001) Pricing U.S. North Atlantic Bluefin Tuna and implications for management. Agribusiness 17:243–254

Chamberlain G (1982) Multi variate regression models for panel data. J Econom 18:5–46

Costello C, Gaines SD, Lynham J (2008) Can catch shares prevent fisheries collapse? Science 321:1678–1681

Delgado CL, Wada N, Rosegrant MW, Meijer S, Ahmed M (2003) Outlook for fish to 2020: meeting global demand. Technical report, International Food Policy Research Institute

Fischer C, Lyon TP (2014) Competing environmental labels. J Econ Manag Strategy 23–3:692–716

Fischer C, Lyon TP (2015) A theory of multi-tier ecolabel competition. Ross school of business paper no. 1319. University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

Hallstein E, Villas-Boas SB (2013) Can household consumers save the wild fish? Lessons from a sustainable seafood advisory. J Environ Econ Manag 66–1:52–71

Hensher DA, Bradley M (1993) Using stated response data to enrich revealed preference discrete choice models. Mark Lett 4–2:139–152

Hilger J, Rafert G, Villas-Boas SB (2011) Expert opinion and the demand for experience goods: an experimental approach in the retail wine market. Rev Econ Stat 93–4:1289–1296

Hoffman D (1987) Two-step generalized least squares estimators in multi-equation generated regressor models. Rev Econ Stat 69–2:336–346

Ippolito P, Mathios AD (1995) Information and advertising: the case of fat consumption in the United States. Am Econ Rev 85–2:91–95

Jaffry S, Pickering H, Ghulam Y, Whitmarsh D, Wattage P (2004) Consumer choices for quality and sustainability labeled seafood products in the U.K. Food Policy 29:215–228

Jin G, Leslie P (2003) The effect of information on product quality: evidence from restaurant hygiene grade cards. Q J Econ 118:409–451

Johnston RJ, Roheim CA (2006) A battle of taste and environmental convictions for eco-labeled seafood: a contingent ranking experiment. J Agric Resour Econ 31:283–300

Johnston RJ, Wessells CR, Donath H, Asche F (2001) Measuring consumer preferences for eco-labeled seafood: an international comparisons. J Agric Resour Econ 26:20–39

Kiesel K, Villas-Boas SB (2007) Got organic milk? Consumer valuations of milk labels after the implementation of the USDA organic seal. J Agric Food Ind Organ 5:4

Mathios AD (2000) The impact of mandatory disclosure laws on product choices: an analysis of the salad dressing market. J Law Econ 42–2:651–677

McConnell K, Strand I (2000) Hedonic prices for fish: Tuna prices in Hawaii. Am J Agric Econ 82:133–144

McFadden D (1974) The measurement of urban travel demand. J Public Econ 3:303–328

McFadden D, Train KE (2000) Mixed MNL models for discrete response. J Appl Econom 15:447–470

Nevo A (2000) A practitioner’s guide to estimation of random-coefficients logit models of demand. J Econ Manag Strategy 9:513–548

Nevo A (2001) Measuring market power in the ready-to-eat cereal industry. Econometrica 69(2):307–342

Nevo A (2003) New products, quality changes and welfare measures computed from estimated demand systems. Rev Econ Stat 85:266–275

Nimon W, Beghin J (1999) Are eco-labels valuable? Evidence from the apparel industry. Am J Agric Econ 81–4:801–811

Pagan A (1984) Econometric issues in the analysis of regressions with generated regressors. Int Econ Rev 25–1:221–247

Roheim CA (2003) Early indications of market impacts from the marine stewardship council’s eco-labeling of seafood. Mar Resour Econ 18:95–104

Roheim CA, Gardiner L, Asche F (2007) Value of brands and other attributes: hedonic analysis of retail frozen fish in the UK. Mar Resour Econ 22–3:239–253

Roheim CA, Asche F, Santos JL (2011) The elusive price premium for eco-labeled products: evidence from seafood in the UK market. J Agric Econ 62–3:655–668

Seafoodwatch (2014) Fishing and farming methods. Monterey Bay Aquarium. May 6th, 2014. http://www.seafoodwatch.org/cr/cr_seafoodwatch/sfw_gear.aspx

Shimshack J, Ward M, Beatty T (2007) Mercury advisories: information, education, and fish consumption. J Environ Econ Manag 53–2:158–179

Smith MD, Roheim CA, Crowder LB, Halpern BS, Turnipseed M, Anderson JL, Asche F, Bourillón L, Guttormsen AG, Khan A, Liguori LA, McNevin A, O’Connor MO, Squires D, Tyedmers P, Brownstein C, Carden K, Klinger DH, Sagarin R, Selkoe KA (2010) Sustainability and global seafood. Science 327:784–786

Sogn-Grundvåg G, Larsen T, Young J (2013) The value of line-caught and other attributes: an exploration of price premiums for chilled fish in UK supermarkets. Mar Policy 38:41–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2012.05.017

Sun J, Chiang F, Owens M, Squires D (2017) Will American consumers pay more for eco-friendly labeled canned tuna? Estimating US consumer demand for canned tuna varieties using scanner data. Mar Policy 79:62–69

Swait J, Adamowicz W, van Bueren M (2004) Choice and temporal welfare impacts: incorporating history into discrete choice models. J Environ Econ Manag 47–1:94–116

Teisl MF, Roe B, Hicks RL (2002) Can eco-labels tune a market? Evidence from dolphin-safe labeling. J Environ Econ Manag 43–3:339–359

Teisl MF, Fromberg E, Smith AE, Boyle KJ, Engelberth HM (2011) Awake at the switch: improving fish consumption advisories for at-risk women. Sci Total Environ 409–18:3257–3266

Train K (2003) Discrete choice methods with simulation. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Watson R, Pauly D (2001) Systematic distortions in world fisheries catch trends. Nature 414:534–536

Funding

Funding was provided by California Sea Grant College Program (Grant No. Project: R/RCC-02, NA10OAR417 0060).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Seafood Sales Shares and Units

The share of seafood sales and units of seafood sold over time for all seafood products and stratified by green, yellow, and red ratings are presented in Figure A1 and Figure A2.

1.2 Total Traffic and Total Seafood Sales

Table 9 reports results of two difference-in-differences specifications on the total store traffic at the store-week level and total seafood purchases at the store-week level. Estimation results indicate that total store traffic was constant when controlling for both store-level and time-periods (Column 1). However, results indicate that seafood sales decreased when controlling for both store-level and time period (Column 2). Taken together, these two results suggest that the total share of non-seafood purchases in the treatment store increased during the treatment period.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hilger, J., Hallstein, E., Stevens, A.W. et al. Measuring Willingness to Pay for Environmental Attributes in Seafood. Environ Resource Econ 73, 307–332 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-018-0264-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-018-0264-6