Abstract

Objective

The P300 event-related potential reflects high-level cognitive processing; it is also sensitive to attentional modulation, impeding its use in malingering detection. Can this be overcome by particularly salient stimuli, e.g., motion or faces?

Methods

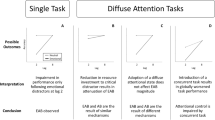

In 11 subjects, we ran two concurrent, uncorrelated oddball sequences (“main sequence” and “distractor sequence”). We modulated the subjects’ attention via three types of tasks: (1) count main oddballs, (2) passive viewing, and (3) count distractor oddballs. For the main sequence, the frequent stimulus was homogeneously gray, and oddballs were (a) stationary gratings, (b) moving gratings, or (c) faces. For the distractor sequence, the frequent stimulus was a black fixation target, with a white fixation target as oddball.

Results

P300 amplitudes were larger for faces than for stationary and moving gratings. Median P300 amplitudes were largest when attending; the P300 was substantially reduced in the “passive” condition (down to 30 % for gratings and down to 80 % for faces) and somewhat more for the “distraction” condition (down to 40 % for gratings and down to 55 % for faces). With distraction, significant P300s occurred in 9 of 11 subjects for faces, only in 5 or 4 with stationary or moving gratings, respectively.

Conclusions

Face-evoked P300s were more resistant to distraction than those to stationary or moving gratings. This provides support for the socio-cognitive role of faces being associated with privileged processing mechanisms. Attentional modulation of P300 depends on stimulus category. Face stimuli may help to objectively access higher level processing while minimizing willful influences.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Howard JE, Dorfman LJ (1986) Evoked potentials in hysteria and malingering. J Clin Neurophysiol 3:39–49

Villegas RB, Ilsen PF (2007) Functional vision loss: a diagnosis of exclusion. Optometry 78:523–533

Towle VL, Harter MR (1977) Objective determination of human visual acuity: pattern evoked potentials. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 16:1073–1076

Teping C (1981) Determination of visual acuity by the visually evoked cortical potential (author’s transl). Klin Monbl Augenheilkd 179:169–172

Odom JV, Hoyt CS, Marg E (1981) Effect of natural deprivation and unilateral eye patching on visual acuity of infants and children: evoked potential measurements. Arch Ophthalmol 99:1412–1416

Röver J, Bach M (1987) Pattern electroretinogram plus visual evoked potential: a decisive test in patients suspected of malingering. Doc Ophthalmol 66:245–251

Nakamura A, Akio T, Matsuda E, Wakami Y (2001) Pattern visual evoked potentials in malingering. J Neuroophthalmol 21:42–45

McBain VA, Robson AG, Hogg CR, Holder GE (2007) Assessment of patients with suspected non-organic visual loss using pattern appearance visual evoked potentials. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 245:502–510

Bach M, Maurer JP, Wolf ME (2008) Visual evoked potential-based acuity assessment in normal vision, artificially degraded vision, and in patients. Br J Ophthalmol 92:396–403

Mackay AM, Bradnam MS, Hamilton R, Elliot AT, Dutton GN (2008) Real-time rapid acuity assessment using VEPs: development and validation of the step VEP technique. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 49:438–441

Almoqbel F, Leat SJ, Irving E (2008) The technique, validity and clinical use of the sweep VEP. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 28:393–403

Di Russo F, Martinez A, Sereno MI, Pitzalis S, Hillyard SA (2002) Cortical sources of the early components of the visual evoked potential. Hum Brain Mapp 15:95–111

Jiraskova N, Kuba M, Kremlacek J, Rozsival P (2011) Normal sensory and absent cognitive electrophysiological responses in functional visual loss following chemical eye burn. Doc Ophthalmol 123:51–57

Sutton S, Braren M, Zubin J, John ER (1965) Evoked-potential correlates of stimulus uncertainty. Science 150:1187–1188

Linden DEJ (2005) The p300: where in the brain is it produced and what does it tell us? Neuroscientist 11:563–576

Katayama J, Polich J (1999) Auditory and visual P300 topography from a 3 stimulus paradigm. Clin Neurophysiol 110:463–468

Picton TW (1992) The P300 wave of the human event-related potential. J Clin Neurophysiol 9:456–479

Gratton G, Bosco CM, Kramer AF, Coles MG, Wickens CD, Donchin E (1990) Event-related brain potentials as indices of information extraction and response priming. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 75:419–432

Sangal B, Sangal JM (1996) Topography of auditory and visual P300 in normal adults. Clin Electroencephalogr 27:145–150

Duncan-Johnson CC, Donchin E (1977) On quantifying surprise: the variation of event-related potentials with subjective probability. Psychophysiology 14:456–467

Fein G, Turetsky B (1989) P300 latency variability in normal elderly: effects of paradigm and measurement technique. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 72:384–394

Ramachandran G, Porjesz B, Begleiter H, Litke A (1996) A simple auditory oddball task in young adult males at high risk for alcoholism. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 20:9–15

Barrett G, Neshige R, Shibasaki H (1987) Human auditory and somatosensory event-related potentials: effects of response condition and age. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 66:409–419

Soltani M, Knight RT (2000) Neural origins of the P300. Crit Rev Neurobiol 14:199–224

Polich J (2003) Theoretical overview of P3a and P3b. In: Polich J (ed) Detection of change. Springer, US, pp 83–98

Polich J (2004) Neuropsychology of P3a and P3b: a theoretical overview. Brainwaves and mind: recent developments. Wheaton, Kjellberg, pp 15–29

Rosenfeld JP, Biroschak JR, Kleschen MJ, Smith KM (2005) Subjective and objective probability effects on P300 amplitude revisited. Psychophysiology 42:356–359

Hansenne M (2000) Le potentiel évoqué cognitif P300 (I): aspects théorique et psychobiologique. Neurophysiol Clin 30:191–210

Polich J (2007) Updating P300: an integrative theory of P3a and P3b. Clin Neurophysiol 118:2128–2148

Towle VL, Sutcliffe E, Sokol S (1985) Diagnosing functional visual deficits with the P300 component of the visual evoked potential. Arch Ophthalmol 103:47–50

Lorenz J, Kunze K, Bromm B (1998) Differentiation of conversive sensory loss and malingering by P300 in a modified oddball task. NeuroReport 9:187–191

Heinrich SP, Marhöfer D, Bach M (2010) “Cognitive” visual acuity estimation based on the event-related potential P300 component. Clin Neurophysiol 121:1464–1472

Becker DE, Shapiro D (1980) Directing attention toward stimuli affects the P300 but not the orienting response. Psychophysiology 17:385–389

Heinze HJ, Luck SJ, Mangun GR, Hillyard SA (1990) Visual event-related potentials index focused attention within bilateral stimulus arrays. I. Evidence for early selection. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 75:511–527

Polich J, Kok A (1995) Cognitive and biological determinants of P300: an integrative review. Biol Psychol 41:103–146

Polich J, Corey-Bloom J (2005) Alzheimer’s disease and P300: review and evaluation of task and modality. Curr Alzheimer Res 2:515–525

Saevarsson S, Kristjánsson Á, Bach M, Heinrich SP (2012) P300 in neglect. Clin Neurophysiol 123:496–506

Rosenfeld JP, Soskins M, Bosh G, Ryan A (2004) Simple, effective countermeasures to P300-based tests of detection of concealed information. Psychophysiology 41:205–219

Bargh JA (1982) Attention and automaticity in the processing of self-relevant information. J Pers Soc Psychol 43:425–436

Abrams RA, Christ SE (2003) Motion onset captures attention. Psychol Sci 14:427–432

Dehaene S, Changeux J-P (2011) Experimental and theoretical approaches to conscious processing. Neuron 70:200–227

Livingstone M, Hubel D (1988) Segregation of form, color, movement, and depth: anatomy, physiology, and perception. Science 240:740–749

Changizi MA, Zhang Q, Shimojo S (2006) Bare skin, blood and the evolution of primate colour vision. Biol Lett 2:217–221

Sergent J, Ohta S, MacDonald B (1992) Functional neuroanatomy of face and object processing. A positron emission tomography study. Brain 115(Pt 1):15–36

Kanwisher N, McDermott J, Chun MM (1997) The fusiform face area: a module in human extrastriate cortex specialized for face perception. J Neurosci 17:4302–4311

Meijer EH, Smulders FTY, Merckelbach HLGJ, Wolf AG (2007) The P300 is sensitive to concealed face recognition. Int J Psychophysiol 66:231–237

World Medical Association (2000) Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. J Am Med Assoc 284:3043–3045

Bex PJ, Makous W (2002) Spatial frequency, phase, and the contrast of natural images. J Opt Soc Am A Opt Image Sci Vis 19:1096–1106

Heinrich SP, Bach M (2008) Signal and noise in P300 recordings to visual stimuli. Doc Ophthalmol 117:73–83

Chertoff ME, Goldstein R, Mease MR (1988) Early event-related potentials with passive subject participation. J Speech Hear Res 31:460–465

Katayama J, Polich J (1996) P300, probability, and the three-tone paradigm. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 100:555–562

American Clinical Neurophysiology Society (2006) Guideline 5: guidelines for standard electrode position nomenclature. J Clin Neurophysiol 23:107–110

Efron B (1979) Bootstrap methods: another look at the jackknife. Ann Stat 7:1–26

Jeffreys DA, Axford JG (1972) Source locations of pattern-specific components of human visual evoked potentials. I. Component of striate cortical origin. Exp Brain Res 16:1–21

Odom JV, Bach M, Brigell M, Holder GE, McCulloch DL, Tormene AP, Vaegan (2010) ISCEV standard for clinical visual evoked potentials (2009 update). Doc Ophthalmol 120:111–119

Jeffreys DA (1989) A face-responsive potential recorded from the human scalp. Exp Brain Res 78:193–202

Bötzel K, Grüsser O-J (1989) Electric brain potentials evoked by pictures of faces and non-faces: a search for “face-specific” EEG-potentials. Exp Brain Res 77:349–360

Joyce C, Rossion B (2005) The face-sensitive N170 and VPP components manifest the same brain processes: the effect of reference electrode site. Clin Neurophysiol 116:2613–2631

Eimer M (2011) The face-sensitivity of the N170 component. Front Hum Neurosci. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2011.00119

Tacikowski P, Nowicka A (2010) Allocation of attention to self-name and self-face: an ERP study. Biol Psychol 84:318–324

Cherry EC (1953) Some experiments on the recognition of speech, with one and with two ears. J Acoust Soc Am 25:975–979

Moray N (1959) Attention in dichotic listening: affective cues and the influence of instructions. Q J Exp Psychol 11:56–60

Wolford G, Morrison F (1980) Processing of unattended visual information. Mem Cognit 8:521–527

Wood N, Cowan N (1995) The cocktail party phenomenon revisited: how frequent are attention shifts to one’s name in an irrelevant auditory channel? J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn 21:255–260

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (BA 877/18 and BA 877/21). We are grateful to our subjects for their participation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Marhöfer, D.J., Bach, M. & Heinrich, S.P. Faces are more attractive than motion: evidence from two simultaneous oddball paradigms. Doc Ophthalmol 128, 201–209 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10633-014-9434-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10633-014-9434-1