Abstract

Background

The risk of metachronous advanced neoplasia after diagnosing serrated polyps in patients with IBD is poorly understood.

Methods

A retrospective multicenter cohort study was conducted between 2010 and 2019 at three tertiary centers in Montreal, Canada. From pathology databases, we identified 1587 consecutive patients with serrated polyps (sessile serrated lesion, traditional serrated adenoma, or serrated epithelial change). We included patients aged 45–74 and excluded patients with polyposis, colorectal cancer, or no follow-up. The primary outcome was the risk of metachronous advanced neoplasia (advanced adenoma, advanced serrated lesion, or colorectal cancer) after index serrated polyp, comparing patients with and without IBD.

Results

477 patients with serrated polyps were eligible (mean age 61 years): 37 with IBD, totaling 45 serrated polyps and 440 without IBD, totaling 586 serrated polyps. The median follow-up was 3.4 years. There was no difference in metachronous advanced neoplasia (HR 0.77, 95% CI 0.32–1.84), metachronous advanced adenoma (HR 0.54, 95% CI 0.11–2.67), and metachronous advanced serrated lesion (HR 0.76, 95% CI 0.26–2.18) risk. When comparing serrated polyps in mucosa involved or uninvolved with IBD, both groups had similar intervals from IBD to serrated polyp diagnosis (p > 0.05), maximal therapies (p > 0.05), mucosal inflammation, inflammatory markers, and fecal calprotectin (p > 0.05).

Conclusion

The risk of metachronous advanced neoplasia after serrated polyp detection was similar in patients with and without IBD. Serrated polyps in IBD occurred independently of inflammation. This helps inform surveillance intervals for patients with IBD diagnosed with serrated polyps.

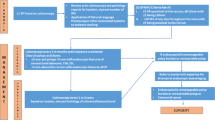

Graphical Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- AA:

-

Advanced adenoma

- ASL:

-

Advanced serrated lesion

- CRC:

-

Colorectal cancer

- ESGE:

-

European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

- HP:

-

Hyperplastic polyp

- IBD:

-

Inflammatory bowel disease

- MAN:

-

Metachronous advanced neoplasia

- SEC:

-

Serrated epithelial change

- SP:

-

Serrated polyp

- SP-IA:

-

Serrated polyp in an involved area of the colon in IBD

- SP-UA:

-

Serrated polyp in an uninvolved area of the colon in IBD

- SSL:

-

Sessile serrated lesion

- TSA:

-

Traditional serrated adenoma

- USMSTF:

-

United States Multi Society Task Force

References

Farraye FA, Odze RD, Eaden J, Itzkowitz SH. AGA technical review on the diagnosis and management of colorectal neoplasia in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:746–74, 74.e1–4; quiz e12–3.

Klepp P, Brackmann S, Cvancarova M, Hoivik ML, Hovde Ø, Henriksen M et al. Risk of colorectal cancer in a population-based study 20 years after diagnosis of ulcerative colitis: results from the IBSEN study. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2020;7:e000361.

Jess T, Simonsen J, Jørgensen KT, Pedersen BV, Nielsen NM, Frisch M. Decreasing risk of colorectal cancer in patients with inflammatory bowel disease over 30 years. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:375–81.e1; quiz e13–4.

Söderlund S, Brandt L, Lapidus A, Karlén P, Broström O, Löfberg R, et al. Decreasing time-trends of colorectal cancer in a large cohort of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1561–7; quiz 818–9.

Lashner BA, Silverstein MD, Hanauer SB. Hazard rates for dysplasia and cancer in ulcerative colitis. Results from a surveillance program. Dig Dis Sci. 1989;34:1536–41.

Ekbom A, Helmick C, Zack M, Adami HO. Ulcerative colitis and colorectal cancer. A population-based study. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:1228–33.

Gupta RB, Harpaz N, Itzkowitz S, Hossain S, Matula S, Kornbluth A, et al. Histologic inflammation is a risk factor for progression to colorectal neoplasia in ulcerative colitis: a cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1099–105; quiz 340–1.

Matkowskyj KA, Chen ZE, Rao MS, Yang G-Y. Dysplastic lesions in inflammatory bowel disease: molecular pathogenesis to morphology. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:338–350.

Azer SA. Overview of molecular pathways in inflammatory bowel disease associated with colorectal cancer development. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25:271–281.

Laine L, Kaltenbach T, Barkun A, McQuaid KR, Subramanian V, Soetikno R. SCENIC international consensus statement on surveillance and management of dysplasia in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:639–51.e28.

Lengauer C, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Genetic instabilities in human cancers. Nature. 1998;396:643–649.

Rex DK, Ahnen DJ, Baron JA, Batts KP, Burke CA, Burt RW, et al. Serrated Lesions of the colorectum: review and recommendations from an expert panel. Am Coll Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1315–29; quiz 1314, 1330.

Snover DC. Update on the serrated pathway to colorectal carcinoma. Human Pathology. 2011;42:1–10.

Weisenberger DJ, Siegmund KD, Campan M, Young J, Long TI, Faasse MA et al. CpG island methylator phenotype underlies sporadic microsatellite instability and is tightly associated with BRAF mutation in colorectal cancer. Nat Genet 2006;38:787–793.

Nagtegaal ID, Odze RD, Klimstra D, Paradis V, Rugge M, Schirmacher P et al. The 2019 WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. Histopathology. 2020;76:182–188.

Parian A, Koh J, Limketkai BN, Eluri S, Rubin DT, Brant SR et al. Association between serrated epithelial changes and colorectal dysplasia in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;84:87–95.e1.

Parian AM, Limketkai BN, Chowdhury R, Brewer GG, Salem G, Falloon K et al. Serrated epithelial change is associated with high rates of neoplasia in ulcerative colitis patients: a case-controlled study and systematic review with meta-analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021;27:1475–1481.

Jackson WE, Achkar JP, Macaron C, Lee L, Liu X, Pai RK et al. The significance of sessile serrated polyps in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:2213–2220.

Ko HM, Harpaz N, McBride RB, Cui M, Ye F, Zhang D et al. Serrated colorectal polyps in inflammatory bowel disease. Mod Pathol. 2015;28:1584–1593.

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370:1453–1457.

Djinbachian R, Lafontaine M, Anderson JC, Pohl H, Dufault T, Boivin M, Bouin M, von Renteln D. Risk of total metachronous advanced neoplasia at surveillance colonoscopy after detection of serrated lesions: a matched cohort study. Endoscopy. 2023;55:728–736.

Vennelaganti S, Cuatrecasas M, Vennalaganti P, Kennedy KF, Srinivasan S, Patil DT et al. Interobserver agreement among pathologists in the differentiation of sessile serrated from hyperplastic polyps. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:452–4.e1.

Schachschal G, Sehner S, Choschzick M, Aust D, Brandl L, Vieth M et al. Impact of reassessment of colonic hyperplastic polyps by expert GI pathologists. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2016;31:675–683.

Howdle P, Atkin W, Rutter M, Jankowski J, Fox B, Makin C, et al. NICE Clinical Guideline 118: Colonoscopic surveillance for prevention of colorectal cancer in people with ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease or adenomas. NICE Publication. 2011. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE).

Schoenfeld DA. Sample-size formula for the proportional-hazards regression model. Biometrics. 1983;39:499–503.

Lash RH, Genta RM, Schuler CM. Sessile serrated adenomas: prevalence of dysplasia and carcinoma in 2139 patients. J Clin Pathol. 2010;63:681–686.

Leddin D, Enns R, Hilsden R, Fallone CA, Rabeneck L, Sadowski DC et al. Colorectal cancer surveillance after index colonoscopy: guidance from the Canadian Association of Gastroenterology. Can J Gastroenterol. 2013;27:224–228.

Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, Smith RA, Brooks D, Andrews KS et al. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:130–160.

Lieberman DA, Rex DK, Winawer SJ, Giardiello FM, Johnson DA, Levin TR. Guidelines for colonoscopy surveillance after screening and polypectomy: a consensus update by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:844–857.

Gupta S, Lieberman D, Anderson JC, Burke CA, Dominitz JA, Kaltenbach T et al. Recommendations for follow-up after colonoscopy and polypectomy: a consensus update by the US multi-society task force on colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1131–53.e5.

Hassan C, Antonelli G, Dumonceau JM, Regula J, Bretthauer M, Chaussade S et al. Post-polypectomy colonoscopy surveillance: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline—Update 2020. Endoscopy. 2020;52:687–700.

Annese V, Beaugerie L, Egan L, Biancone L, Bolling C, Brandts C et al. European evidence-based consensus: inflammatory bowel disease and malignancies. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9:945–965.

Magro F, Gionchetti P, Eliakim R, Ardizzone S, Armuzzi A, Barreiro-de Acosta M et al. Third European evidence-based consensus on diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis. Part 1: definitions, diagnosis, extra-intestinal manifestations, pregnancy, cancer surveillance, surgery, and ileo-anal pouch disorders. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:649–70.

Shen J, Gibson JA, Schulte S, Khurana H, Farraye FA, Levine J et al. Clinical, pathologic, and outcome study of hyperplastic and sessile serrated polyps in inflammatory bowel disease. Hum Pathol. 2015;46:1548–1556.

Crockett SD, Nagtegaal ID. Terminology, molecular features, epidemiology, and management of serrated colorectal neoplasia. Gastroenterology. 2019;157:949–66.e4.

Hyun E, Helewa RM, Singh H, Wightman HR, Park J. Serrated polyps and polyposis of the colon: a brief review for surgeon endoscopists. Can J Surg. 2021;64:E561.

Jaravaza DR, Rigby JM. Hyperplastic polyp or sessile serrated lesion? The contribution of serial sections to reclassification. Diagn Pathol. 2020;15:140.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Alan Barkun (McGill University), MD, CM, MSc (Clinical Epidemiology), for his significant contribution to the review of this research project. The authors also thank Miguel Chagnon, MSc, statistician, and our research coordinators, Julie Fleury, MSc and Samira Hanin, MSc, for their help in bringing this project to fruition.

Funding

There was no funding for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Edgard Medawar contributed to Study concept and design; acquisition of data; statistical analysis; drafting of the manuscript; and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Roupen Djinbachian contributed to Study concept and design; acquisition of data; and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Ioana Popescu Crainic contributed to Acquisition of data and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Widad Safih contributed to Acquisition of data and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Robert Battat contributed to Study concept and design and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Jeffrey McCurdy contributed to Study concept and design and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Peter L Lakatos contributed to Study concept and design and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Daniel von Renteln contributed to Study concept and design; drafting of the manuscript; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; and study supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Edgard Medawar, Roupen Djinbachian, Ioana Popescu Crainic, Widad Safih, Jeffrey McCurdy, Robert Battat, Peter L Lakatos, and Daniel von Renteln have no conflicts of interest relevant to this paper to declare.

Ethical approval

This retrospective chart review study involving human participants was in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Montreal Hospital Center (approval number #CER 21.193). There was no direct patient involvement given the retrospective nature of this study. Confidentiality of the data collected was maintained through anonymization, data encryption, restricted database access, and adherence to local good clinical practice guidelines.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Medawar, E., Djinbachian, R., Crainic, I.P. et al. Serrated Polyps in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Indicate a Similar Risk of Metachronous Colorectal Neoplasia as in the General Population. Dig Dis Sci (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-024-08456-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-024-08456-z