Abstract

Background

Despite recent advances and better understanding of the etiology and the pathogenesis of gastrointestinal ulcer diseases, e.g., duodenal ulcer, the molecular events leading to ulcer development, delayed healing, and recurrence remain poorly elucidated.

Aims

After we found that duodenal ulcers did not heal despite increased levels of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), we tested the hypothesis that an imbalance in angiogenic VEGF and anti-angiogenic endostatin and angiostatin might be important in the development and delayed healing of experimental duodenal ulcers.

Methods

Levels of VEGF, endostatin, and angiostatin, and the expression and activity of related matrix metalloproteinases (MMP) 2 and 9 were measured in scrapings of rat proximal duodenal mucosa in the early and late stages of chemically induced duodenal ulceration. Furthermore, animals were treated with recombinant endostatin and MMP 2 inhibitor to test the relationship between MMP2 and endostatin and their involvement in healing of experimental duodenal ulcers.

Results

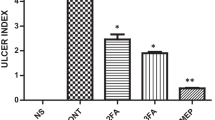

A concurrent increase of duodenal VEGF, endostatin, and angiostatin was noted during duodenal ulceration. Endostatin treatment aggravated duodenal ulcer. Levels of MMP2, but not MMP9, were increased. Inhibition of MMP2 reduced levels of endostatin and angiostatin, and attenuated duodenal ulcers.

Conclusions

Increased levels of endostatin and angiostatin induced by MMP2 delayed healing of duodenal ulcers despite concurrently increased VEGF. Thus, an inappropriate angiogenic response or “angiogenic imbalance” may be an important new mechanism in ulcer development and impaired healing.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Sonnenberg A, Everhart JE. Health impact of peptic ulcer in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:614–620.

Bytzer P, Teglbjaerg PS. Danish Ulcer Study Group. Helicobacter pylori-negative duodenal ulcers: prevalence, clinical characteristics, and prognosis—results from a randomized trial with 2-year follow-up. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1409–1416.

Kong SX, Hatoum HT, Zhao SZ, Agrawal NM, Geis SG. Prevalence and cost of hospitalization for gastrointestinal complications related to peptic ulcers with bleeding or perforation: comparison of two national databases. Am J Manag Care. 1998;4:399–409.

Manuel D, Cutler A, Goldstein J, Fennerty MB, Brown K. Decreasing prevalence combined with increasing eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection in the United States has not resulted in fewer hospital admissions for peptic ulcer disease-related complications. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:1423–1427.

Chan FK, Leung WK. Peptic-ulcer disease. Lancet. 2002;360:933–941.

Jayaraj AP, Tovey FI, Lewin MR, Clark CG. Duodenal ulcer prevalence: experimental evidence for the possible role of dietary lipids. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;15:610–616.

Selye H, Szabo S. Experimental model for production of perforating duodenal ulcers by cysteamine in the rat. Nature. 1973;244:458–459.

Szabo S, Reynolds ES, Unger SH. Structure-activity relations between alkyl nucleophilic chemicals causing duodenal ulcer and adrenocortical necrosis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1982;223:68–76.

Fukuhara S, Suzuki H, Masaoka T, et al. Enhanced ghrelin secretion in rats with cysteamine-induced duodenal ulcers. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;289:G138–G145.

Szabo S, Shing Y, Folkman MJ, et al. Angiogenesis and growth factors in ulcer healing. In: Fan Tai-Ping D, Kohn EC, eds. New Angiogenesis. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press, 2001;119–211.

Folkman J. Angiogenesis. Annu Rev Med. 2006;57:1–18.

Pandya NM, Dhalla NS, Santani DD. Angiogenesis—a new target for future therapy. Vascul Pharmacol. 2006;44:265–274.

Vincze A, Nagata M, Sandor Zs, Szabo S. ELISA and western blot studies with basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) in experimental duodenal ulceration and healing. Inflammopharmacology. 1996;4:261–265.

Szabo S, Vincze A, Sandor Zs, et al. Vascular approach to gastroduodenal ulceration: new studies with endothelins and VEGF. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43(9 Suppl):40S–45S.

Folkman J, Szabo S, Stovroff M, McNeil P, Li W, Shing Y. Duodenal ulcer: discovery of a new mechanism and development of angiogenic therapy that accelerates healing. Ann Surg. 1991;214:414–426.

Szabo S, Kusstatscher S, Sakoulas G, Sandor Z, Vincze A, Jadus M. Growth factors: new ‘endogenous drugs’ for ulcer healing. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1995;30:15–18.

Deng X, Szabo S, Khomenko T, Jadus MR, Yoshida M. Gene therapy with naked DNA or adenoviral vector of VEGF or PDGF increases endogenous VEGF, PDGF and bFGF expression and accelerates chronic duodenal ulcer healing in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;311:982–988.

Szabo S, Vincze A. Growth factors in ulcer healing: lessons from recent studies. J Physiol (Paris). 2000;94:77–81.

Hanahan D, Folkman J. Patterns and emerging mechanisms of the angiogenic switch during tumorigenesis. Cell. 1996;86:353–364.

O’Reilly MS, Holmgren L, Shing Y, et al. Angiostatin: a novel angiogenesis inhibitor that mediates the suppression of metastases by a Lewis lung carcinoma. Cell. 1994;79:315–328.

O’Reilly MS, Boehm T, Shing Y, et al. Endostatin: an endogenous inhibitor of angiogenesis and tumor growth. Cell. 1997;88:277–285.

Distler JH, Hirth A, Kurowska-Stolarska M, Gay RE, Gay S, Distler O. Angiogenic and angiostatic factors in the molecular control of angiogenesis. Q J Nucl Med. 2003;47:149–161.

Heljasvaara R, Nyberg P, Luostarinen J, et al. Generation of biologically active endostatin fragments from human collagen XVIII by distinct matrix metalloproteases. Exp Cell Res. 2005;307:292–304.

Claesson-Welsh L, Welsh M, Ito N, et al. Angiostatin induces endothelial cell apoptosis and activation of focal adhesion kinase independently of the integrin-binding motif RGD. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:5579–5583.

Taddei L, Chiarugi P, Brogelli L, et al. Inhibitory effect of full-length human endostatin on in vitro angiogenesis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;263:340–345.

Rundhaug JE. Matrix metalloproteinases and angiogenesis. J Cell Mol Med. 2005;9:267–285.

Sandor Z, Deng XM, Khomenko T, Tarnawski AS, Szabo S. Altered angiogenic balance in ulcerative colitis: a key to impaired healing? Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;350:147–150.

Deng X, Tolstanova G, Khomenko T, et al. Mesalamine restores angiogenic balance in experimental ulcerative colitis by reducing expression of endostatin and angiostatin: novel molecular mechanism for therapeutic action of mesalamine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;331:1071–1078.

Smith E, Hoffman R. Multiple fragments related to angiostatin and endostatin in fluid from venous leg ulcers. Wound Rep Reg. 2005;13:148–157.

Bucalo B, Eaglstein WH, Falanga V. Inhibition of cell proliferation by chronic wound fluid. Wound Rep Reg. 1993;1:181–186.

Drinkwater SL, Smith A, Sawyer BM, Burnand KG. Effect of venous ulcer exudates on angiogenesis in vitro. Br J Surg. 2002;89:709–713.

Drinkwater SL, Burnand KG, Ding R, Smith A. Increased but ineffectual angiogenic drive in non-healing venous leg ulcers. J Vasc Surg. 2003;38:1106–1112.

Ma L, Elliott SN, Cirino G, Buret A, Ignarro LJ, Wallace JL. Platelets modulate gastric ulcer healing: role of endostatin and vascular endothelial growth factor release. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:6470–6475.

Kato M, Wang H, Kainulainen V, et al. Physiological degradation converts the soluble syndecan-1 ectodomain from an inhibitor to a potent activator of FGF-2. Nat Med. 1998;4:691–697.

Sottile J. Regulation of angiogenesis by extracellular matrix. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1654:13–22.

Weckroth M, Vaheri A, Lauharanta J, Sorsa T, Konttinen YT. Matrix metalloproteinases, gelatinase and collagenase, in chronic leg ulcers. J Invest Dermatol. 1996;106:1119–1124.

Lauer G, Sollberg S, Cole M, et al. Expression and proteolysis of vascular endothelial growth factor is increased in chronic wounds. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:12–18.

Bloch W, Huggel K, Sasaki T, et al. The angiogenesis inhibitor endostatin impairs blood vessel maturation during wound healing. FASEB J. 2000;14:2373–2376.

Boehm T, Folkman J, Browder T, O’Reilly MS. Antiangiogenic therapy of experimental cancer does not induce acquired drug resistance. Nature. 1997;390:404–407.

Yamaguchi N, Anand-Apte B, Lee M, et al. Endostatin inhibits VEGF-induced endothelial cell migration and tumor growth independently of zinc binding. EMBO J. 1999;18:4414–4423.

McDonald NJ, Shivers WY, Narum DL, et al. Endostatin binds tropomyosin: a potential modulator of the antitumor activity of endostatin. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:25190–25196.

Mwaura B, Mahendran B, Hynes N, et al. The impact of differential expression of extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer, matrix metalloproteinase-2, tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase-2 and PDGF-AA on the chronicity of venous leg ulcers. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2006;31:306–310.

Swarnakar S, Mishra A, Ganguly K, Sharma AV. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 activity and expression is reduced by melatonin during prevention of ethanol-induced gastric ulcer in mice. J Pineal Res. 2007;43:56–64.

Mott JD, Werb Z. Regulation of matrix biology by matrix metalloproteinases. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2004;16:558–564.

Cornelius LA, Nehring LC, Harding E, et al. Matrix metalloproteinases generate angiostatin: effects on neovascularization. J Immunol. 1998;161:6845–6852.

Ferreras M, Felbor U, Lenhard T, Olsen BR, Delaissé J. Generation and degradation of human endostatin proteins by various proteinases. FEBS Lett. 2000;486:247–251.

Nilsson UW, Dabrosin C. Estradiol and tamoxifen regulate endostatin generation via matrix metalloproteinase activity in breast cancer in vivo. Cancer Res. 2006;66:4789–4794.

Ito A, Nagase H, Mori Y. Characterization of metalloproteinases in rat gastric tissues with acetic acid-induced ulcers. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1989;162:146–149.

Kobayashi S, Nakajima N, Ito Y, Moriyama M. Effects of lansoprazole on the expression of VEGF and cellular proliferation in a rat model of acetic acid-induced gastric ulcer. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:846–858.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration Merit Review grant and by contributions from CPRC, Inc.

Conflict of interest

No conflicts of interest exist.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Deng, X., Xiong, X., Khomenko, T. et al. Inappropriate Angiogenic Response as a Novel Mechanism of Duodenal Ulceration and Impaired Healing. Dig Dis Sci 56, 2792–2801 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-011-1753-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-011-1753-4