Abstract

Regulatory law enforcement bias in the inspection, charging, and sanctioning process has been linked to the characteristics of offenses, the attributes of the regulatory agencies and the corporation, and the political and economic environment. However, the bargaining process of regulatory agencies has been less thoroughly investigated. To fill this gap in the literature, this study investigates whether certain extralegal variables affect the post-inspection bargaining process at the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). In particular, since previous studies have focused exclusively on fine reductions, this study examines the full range of bargaining options, including count, charge, and fine reductions. Further, this is one of the first studies to directly examine whether company financial resources impact bargaining at OSHA. Because the data are multilevel data, I use multilevel logistic and linear regressions to examine whether extralegal variables affect the reductions given to facilities in the steel, oil, pulp, and paper industries. Specifically, I test whether facility level variables (unionization and experience with the system), company level variables (financial performance and size) and state level variables (political and economic environment) affect the reductions received by facilities during the post-inspection process at OSHA. Although there was some evidence to support the idea that state political views and system familiarity affect bargaining, the results overall tend to cast doubt on the notion that extralegal variables impact the decision-making process at OSHA. Due to sample limitations, the multilevel models employed here are exploratory, but they suggest that previous studies may have overestimated the effects of extralegal variables.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Planned inspections involve random selection of establishments. OSHA designates a given industry as a priority for planned inspections, and then each area office compiles a list of establishments in those industries in their area and selects sites from that list at random [17].

Personal interview with OSHA representative from OSHA Compliance Helpline, December, 4, 2004

Obviously, it is not possible to include every theory so theories were chosen based on their relevance and popularity as explanations for the presence of extralegal variables.

For evidence to the contrary, see Huber [22]. He argues that there are neutral explanations for what appear to be the disparate influence of politics and economic conditions. For example, he argues that politics may affect enforcement outcomes, but that is not the same as saying it affects discretionary decisions. Huber [22] states that “where businesses challenge OSHA inspectors, threaten workers, and appeal citations, OSHA will be slowed despite its best efforts” (p. 161). Similarly, he argues that unemployment affects worker behavior, not OSHA behavior. Huber [22] argues that during times of unemployment, workers are less willing to cooperate with OSHA so OSHA inspectors have a harder time finding violations.

Albonetti [2] reported evidence of this theory within the criminal justice system. In her analysis of 400 offenders charged with burglary and robbery, offenders with prior records received more reductions. Albonetti [2] explained this was due to the familiarity with the system that allowed these offenders to know when to continue negotiating for a better deal.

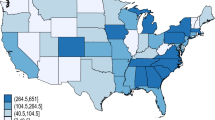

The focus of the original study was on EPA water violations so the four industries were chosen based on their use of water permits and comparable chemicals and because the industries are known water polluters [64]. However, as major manufacturing industries, they are also subject to extensive OSHA regulations. Manufacturing workplaces have long been a focus of OSHA activity [19]. All four industries in this study are covered by OSHA under the General Industry category and monitored for basic regulations that cover all workplaces. Additionally, each industry has standards that apply specifically to that industry. The pulp and paper industries have special regulations for the preparation of pulpwood using power saws and chippers, the chemical process of making pulp using sulfur, and bleaching rooms, machines, and chemicals [60]. The petroleum refining industry has special regulations for the distillation process involved in producing gasoline and for the handling of the chemical by-products [61]. Similarly, the regulations of the steel industry dictate the use of and standards for the blast furnaces and coke ovens involved in the conversion of iron to steel [61]. Further, previous studies have focused on manufacturing industries to examine OSHA violations [11, 18, 31, 34, 38, 43, 50]; Hill et al. [21] reported that the paper and steel industries were among the worst offenders in their sample while oil was an average offender.

While this sample size is smaller than those generally used in OSHA research, some previous studies have utilized comparable sample sizes. For example, Cook and Gautschi [11] examined 113 plants; Weil [72] conducted his study using 250 facilities; Scherer et al. [41] used 555 inspections in their study of differences in OSHA inspection outcomes; and Headrick et al. [20] examined political influence at OSHA using 646 inspections.

Most OSHA studies do not include measures of prior inspections or violations and the few that do have used various periods of time. While Huber [22] suggested that four years was necessary to capture heterogeneity in employer practices and working conditions, McCaffrey [29] argued that one year of previous violations was sufficient to capture plant-specific working conditions. Other studies have used three years; Gray and Medeloff [19] measured priors by determining whether a plant had been inspected within the previous three years. I believe three years is sufficient for measuring familiarity with the system in this sample because every facility had both inspections and violations in that time period.

Because the sample used here is composed of a non-random sub-sample of companies (those that were found in violation upon inspection), I ran the Heckman two-step correction using the full sample, comprised of facilities that were inspected and found in violation and facilities that were inspected and not found in violation, to assess selection bias. The dependent variable was a measure of total violations for each facility so that facilities without violations would be missing data on this measure; those with missing data on the dependent variable are assumed to be not selected in the Heckman model. The Heckman model produced an inverse mills ratio (IMR), which was saved as a new variable in the data. The IMR was checked for collinearity with the other predictor variables, and it had a condition index of 52.569, which is problematic. Despite this, I ran all three models with the IMR as an additional predictor to see whether my other estimates would be affected. In general, the findings do not deviate with the changes in model specification. Because the alternative specification with the Heckman estimator found substantively similar results, and because inclusion of the IMR is problematic due to collinearity, the results of the uncorrected models are reported here.

For the amount of fine reduction, the dependent variable is again censored because not every company that was fined received a fine reduction. Once again, I ran a Heckman selection model. For this model, there were no issues with collinearity. All of the estimates were unaffected by the inclusion of the IMR except for the Federal variable, which became marginally significant, and the Prior Inspections variable, which changed directions and level of significance. Since there were no issues with collinearity and the findings in this model did deviate with the changes in model specification, I present the corrected model for this outcome.

Given the largely insignificant results of size and the financial resource variables (discussed more below), though, this finding raises the question of whether the bargaining stage variable is acting as a proxy for size and the resource variables. These variables were not highly or significantly correlated with bargaining stage, but I explored this question further by running each analysis without the bargaining stage variable. None of the insignificant variables gained significance when bargaining stage was eliminated from the analysis. Further, I created a dichotomous Bargain variable where 1 represented firms that challenged their initial fines, and I ran a multilevel logistic regression to determine whether these variables influenced the decision to challenge the initial fine. Only priors and federal OSHA were significant; both variables were positively significant indicating that firms with more priors and firms operating under federal OSHA were more likely to enter the bargaining process. Based on these results (tables available form the author upon request), bargaining stage does not seem to be acting as a proxy for size or the financial resource variables.

The results generated by the exploration of bargaining stage above lend more evidence to this resource hypothesis. Firms operating under federal OSHA are more likely to challenge violations, and so federal OSHA may be pressured to give more reductions or risk a backlog in its system. As Scholz et al. [44] pointed out, businesses can influence the level of enforcement by threatening or using more appeals, which could divert inspection resources to the appeals process.

This could be particularly relevant for bargaining decisions that are taken to the formal appeal in front of a Federal Review Commission since the president appoints the commissioners. However, this is not a huge issue in my sample because only 9% of cases used the formal Review Commission, and the majority of those cases (77%) were actually in State OSHA states. While it varies, the state governor typically appoints state OSHA review commissioners, and I did control for party affiliation of the governor.

In actuality, 16% of the facilities only have one violation during the study period, which would increase the average across the remaining facilities. Further, a benefit of cross-classified models is that they are explicitly designed to account for sample imbalances [23].

References

Afshartous, D., & de Leeuw, J. (2005). A predictive density approach to predicting a future observable in multilevel models. Journal of Statistical Planning and Inference, 128, 149–164.

Albonetti, C. A. (1992). Charge reduction: an analysis of prosecutorial discretion in burglary and robbery cases. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 8(3), 317–333.

Alexander, C. R., Arlen, J., & Cohen, M. A. (1999). Regulating corporate criminal sanctions: federal guidelines and the sentencing of public firms. Journal of Law and Economics, 42(1), 393–422.

Atlas, M. (2007). Enforcement principles and environmental agencies: principal-agent relationships in a delegated environmental program. Law & Society Review, 41(4), 939–980.

Barnett, H. C. (1981). Corporate capitalism, corporate crime. Crime & Delinquency, 27, 4–23.

Bradbury, J. C. (2006). Regulatory federalism and workplace safety: evidence from OSHA enforcement, 1981-1995. Journal of Regulatory Economics, 29, 211–224.

Calavita, K. (1983). The demise of the occupational safety and health administration: a case study in symbolic action. Social Problems, 30(4), 437–448.

Carmel, M. (1994). OSHA regional penalty reductions inconsistent based on union status. Occupational Health & Safety, 63(10), 147.

Clinard, M. B., & Yeager, P. C. (1980). Corporate crime. New York City: The Free Press.

Cohen, M.A., Ho, C., Jones, E.D. & Schleich, L.M. (1988). Report to the U.S. sentencing commission on sentencing of organizations in the federal courts, 1984–1987. United States Sentencing Commission Discussion Materials on Organizational Sanctions, 1–22.

Cook, W. N., & Gautschi, F. H. (1981). OSHA, plant safety programs, and injury reduction. Industrial Relations, 20(3), 245–257.

Farber, H. S. (1984). Right-to-work laws and the extent of unionization. Journal of Labor Economics, 2(3), 319–352.

Frank, N. K., & Lombness, M. (1988). Controlling corporate illegality: the regulatory justice system. Cincinnati: Anderson Publishing Company.

Freund, P. A., & Holling, H. (2008). Creativity in the classroom: a multilevel analysis investigating the impact of creativity and reasoning ability on GPA. Creativity Research Journal, 20(3), 309–318.

Galanter, M. (1974). Why the “haves” come out ahead: speculation on the limits of legal change. Law & Society Review, 9, 95–160.

Galvin, M. A. (2014). Sentencing corporate crime: responses to scandal and Sarbanes Oxley (unpublished master’s thesis). College Park: University of Maryland.

Gomez, M. (1997). Factors associated with exposures in occupational safety and health administration data. American Industrial Hygiene Association Journal, 58, 186–195.

Gray, W. B., & Jones, C. A. (1991). Longitudinal patterns of compliance with occupational safety and health administration health and safety regulations in the manufacturing sector. The Journal of Human Resources, 26(4), 623–653.

Gray, W. B., & Medeloff, J. M. (2005). The declining effects of OSHA inspections on manufacturing injuries, 1979-1998. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 58(4), 571–587.

Headrick, B., Serra, G., & Twombly, J. (2002). Enforcement and oversight: using congressional oversight to shape OSHA bureaucratic behavior. American Politics Research, 30(6), 608–629.

Hill, C. W. L., Kelley, P. C., Agle, B. R., Hitt, M. A., & Hoskisson, R. E. (1992). An empirical examination of the causes of corporate wrongdoing in the United States. Human Relations , 45(10), 1055–1076.

Huber. (2007). The craft of bureaucratic neutrality: interests and influence in governmental regulation of occupational safety. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Johnson. (2012). Cross-classified multilevel models: an application to the criminal case processing of indicted terrorists. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 28, 163–189.

Jung, J. & Makowsky, M.D. (2013). The determinants of federal and state enforcement of workplace safety regulations: OSHA inspections 1990-2010. Available at SSRN: doi:10.2139/ssrn.2001203

Kim, D. (2007). Political control and bureaucratic autonomy revisited: a multi institutional analysis of OSHA enforcement. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 18, 33–55.

Krull, J. L., & MacKinnon, D. P. (1999). Multilevel mediation modeling in group-based intervention studies. Evaluation Review, 23(4), 418–444.

Luke, D. (2004). Multilevel modeling. Quantitative applications in the social sciences. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Lynxwiler, J., Shover, N., & Clelland, D. A. (1983). The organization and impact of inspector discretion in a regulatory bureaucracy. Social Problems, 30(4), 425–435.

McCaffrey, D. P. (1983). An assessment of OSHA’s recent effects on injury rates. The Journal of Human Resources, 18(1), 131–147.

McKendall, M., Sanchez, C. & Sicilian, P. (1999). Corporate governance and corporate illegality: The effects of board structure on environmental violations. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 7(3), 201–223.

McKendall, M., DeMarr, B., & Jones-Rikkers, C. (2002). Ethical compliance programs and corporate illegality: testing the assumptions of the corporate sentencing guidelines. Journal of Business Ethics, 37(4), 367–383.

Naderi, A., & Mace, J. (2003). Education and earnings: a multilevel analysis a case study of the manufacturing sector in Iran. Economics of Education Review, 22, 143–156.

Pearce, F., & Snider, L. (1995). Regulating capitalism. In F. Pearce & L. Snider (Eds.), Corporate crime: contemporary debates (pp. 19–47). Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press.

Pedersen, D. H. (2000). Industrial responses to constrained OSHA regulation. American Industrial Hygiene Association Journal, 61(3), 381–387.

Piquero, N. L., & Davis, J. L. (2004). Extralegal factors and the sentencing of organizational defendants: an examination of the federal sentencing guidelines. Journal of Criminal Justice, 32, 643–654.

Reichman, N. (1992). Moving backstage: uncovering the role of compliance practices in shaping regulatory policy. In K. Schlegel & D. Weisburd (Eds.), White-collar crime reconsidered (pp. 244–268). Boston: Northeastern University Press.

Rocconi, L. M. (2013). Analyzing multilevel data: comparing findings from hierarchical linear modeling and ordinary least squares regression. Higher Education, 66, 439–461.

Ruser, J. W., & Smith, R. S. (1990). Reestimating OSHA’s effects: have the data changed? The Journal of Human Resources, 26(2), 212–235.

Seligman, P. J., Sieber, W. K., Pedersen, D. H., Sundin, D. S., & Frazier, T. M. (1988). Compliance with OSHA record-keeping requirements. American Journal of Public Health, 78(9), 1218–1219.

Scherer, R. F., Kaufman, D. J., & Aninina, M. F. (1993). Complaint resolution by OSHA in small and large manufacturing firms. Journal of Small Business Management, 31(1), 73–82.

Scherer, R. F., Owen, C. L., & Brodzinski, J. D. (1997). Differences in OSHA safety inspection outcomes: an investigation of regions in two industrial groups. The Mid-Atlantic Journal of Business, 33(2), 137–151.

Schmidt, P. (2002). Pursuing regulatory relief: strategic participation and litigation in U.S. OSHA rulemaking. Business & Politics, 4(1), 71–89.

Scholz, J. T., & Gray, W. B. (1990). OSHA enforcement and workplace injuries: a behavioral approach to risk assessment. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 3, 283–305.

Scholz, J. T., Twombly, J., & Headrick, B. (1991). Street-level political controls over federal bureaucracy. American Political Science Review, 85(3), 829–850.

Scholz, J. T., & Wei, F. H. (1986). Regulatory enforcement in a federalist system. American Political Science Review, 80, 1227–1249.

Shapiro, S. P. (1984). Wayward capitalists: targets of the securities and exchange commission. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Shover, N., Clelland, D. A., & Lynxwiler, J. (1986). Enforcement or negotiation: constructing a regulatory bureaucracy. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Simpson, S. S., Garner, J., & Gibbs, C. (2007). Why do corporations obey the law? Assessing punitive and cooperative strategies of corporate crime control. NIJ Grant: Final Report (#2001-IJ-CX00020). U.S. Department of Justice: National Criminal Justice Reference Service.

Siskind, F. (2002). Twentieth century OSHA enforcement data. Online. Available: www.dol.gov/asp.

Smith, R. S. (1978). The impact of OSHA inspections on manufacturing injury rates. The Journal of Human Resources, 14(2), 145–170.

Snider, L. (1993). Theory and politics in the control of corporate crime. In F. Pearce & M. Woodiwiss (Eds.), Global crime connections: dynamics and control (pp. 212–240). London: Macmillan, and Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Spohn, C., & Holleran, D. (2000). The imprisonment penalty paid by young, unemployed black and Hispanic male offenders. Criminology, 38, 281–306.

Steffensmeier, D. (1980). Assessing the impact of the women’s movement on sex-based differences in the handling of adult criminal defendants. Crime & Delinquency, 26, 344–357.

Steffensmeier, D., & Demuth, D. (2006). Does gender modify the effects of race-ethnicity on criminal sanctioning? Sentences for male and female white, black, and Hispanic defendants. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 22, 241–261.

Steffensmeier, D., Ulmer, J., & Kramer, J. (1998). The interaction of race, gender, and age in criminal sentencing: the punishment cost of being young, black, and male. Criminology, 36, 763–798.

Sunstein, C. R. (2008). Is OSHA unconstitutional? Virginia Law Review, 94(6), 1407–1449.

Tso, G. K. F., & Guan, J. (2014). A multilevel regression approach to understand effects of environment indicators and household features on residential energy consumption. Energy, 66, 722–731.

U.S. Department of Labor (2009). OSHA field operation manual. Online. Available: www.osha.gov.

U.S. Department of Labor (2004a). State occupational safety and health plans. Online. Available: www.osha.gov.

U.S. Department of Labor (2004b). Standards. Online. Available: www.osha.gov.

U.S. Department of Labor (2004c). SIC Codes. Online. Available: www.osha.gov.

U.S. Department of Labor (2003). Employer rights and responsibilities following an OSHA inspection. Available: www.osha.gov.

U.S. Department of Labor (2002). OSHA inspections. OSHA Publication 2098. Online. Available: www.osha.gov.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (1995). Sector notebook project. Office of Compliance: Washington.

Ulmer, J. T., & Johnson, B. (2004). Sentencing in context: a multilevel analysis. Criminology, 42, 137–178.

Viscusi, W. K. (1979). The impact of occupational safety and health regulation. The Bell Journal of Economics, 117–140.

Viscusi, W. K. (1986). The impact of occupational safety and health regulation, 1973-1983. RAND Journal of Economics, 17(4), 567–580.

Visser, J. (2006). Union membership statistics in 24 countries. Monthly Labor Review, 129, 38–49.

Wang, K. (2006). Plea agreement in federal sentencing guidelines for organization cases: a beginning point of retrospective analysis. Paper presented at American Society of Criminology Annual Meeting, Los Angeles, CA.

Ward's Business Directory of U.S. and Private and Public Companies (1995). Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Research Inc.

Weil, D. (1991). Enforcing OSHA: the role of labor unions. Industrial Relations, 30(1), 20–36.

Weil, D. (1996). If OSHA is so bad, why is compliance so good? RAND Journal of Economics, 27(3), 618–640.

Weil, D. (2001). Assessing OSHA performance: new evidence from the construction industry. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 20(4), 651–674.

Yeager, P. C. (1987). Structural bias in regulatory law enforcement: the case of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Social Problems, 34(4), 330–344.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schell-Busey, N. Do extralegal variables impact the post-inspection process of the occupational safety and health administration?. Crime Law Soc Change 68, 187–216 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-017-9681-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-017-9681-7