Abstract

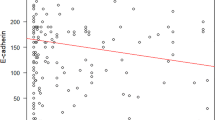

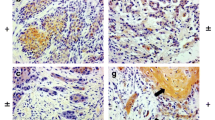

Multiple primary tumors can occur in up to 35 % of the patients with head and neck cancer, however its clinicopathological features remain controversial. Deregulation of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) signaling has been associated with aggressive malignancies and tumor progression to metastasis in several cancer types. This study is the first to explore EMT process in multiple primary oral squamous cell carcinomas (OSCC). Immunohistochemical analysis of E-cadherin, catenin (α, β, and γ), APC, collagen IV, Ki-67, cyclin D1, and CD44 were performed in a tissue microarray containing multiple representative areas from 102 OSCC patients followed-up by at least 10 years. Results were analysed in relation to clinicopathological characteristics and survival rates in patients presenting multiple primary tumors versus patients without second primary tumors or metastatic disease. Significant association was observed among multiple OSCCs and protein expression of E-cadherin (P = 0.002), β-catenin (P = 0.047), APC (P = 0.017), and cyclin D1 (P = 0.001) as well as between lymph nodes metastasis and Ki-67 staining (P = 0.021). OSCCs presenting vascular embolization were associated with negative β-catenin membrane expression (P = 0.050). There was a significantly lower survival probability for patients with multiple OSCC (log-rank test, P < 0.0001), for tumors showing negative protein expression for E-cadherin (log-rank test, P = 0.003) and β-catenin (log-rank test, P = 0.031). Stratified multivariate survival analysis revealed a prognostic interdependence of E-cadherin and β-catenin co-downexpression in predicting the worst overall survival (log-rank test, P = 0.007). EMT markers have a predicted value for invasiveness related to multiple primary tumors in OSCC and co-downregulation of E-cadherin and β-catenin has a significant prognostic impact in these cases.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Billroth T (1882) Die Allgemeine Chirurgische Pathologie und Therapie In 51 Vorlesungen: Ein Handbuch für Studierende und Aerzte. R Riemer, Berlin 980

Gan SJ et al (2013) Incidence and pattern of second primary malignancies in patients with index oropharyngeal cancers versus index nonoropharyngeal head and neck cancers. Cancer 119(14):2593–2601

Bold B et al (2008) Usefulness of PET/CT for detecting a second primary cancer after treatment for squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Clin Nucl Med 33(12):831–833

van Oijen MG et al (2000) The origins of multiple squamous cell carcinomas in the aerodigestive tract. Cancer 88(4):884–893

Stokkel MP et al (1999) 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose dual-head positron emission tomography as a procedure for detecting simultaneous primary tumors in cases of head and neck cancer. Cancer 86(11):2370–2377

McGarry GW et al (1992) Multiple primary malignant tumours in patients with head and neck cancer: the implications for follow-up. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci 17(6):558–562

Liao LJ et al (2013) The impact of second primary malignancies on head and neck cancer survivors: a nationwide cohort study. PLoS One 8(4):e62116

Slaughter DP, Southwick HW, Smejkal W (1953) Field cancerization in oral stratified squamous epithelium; clinical implications of multicentric origin. Cancer 6(5):963–968

Perez-Ordonez B, Beauchemin M, Jordan RC (2006) Molecular biology of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. J Clin Pathol 59(5):445–453

Califano J et al (2000) Genetic progression and clonal relationship of recurrent premalignant head and neck lesions. Clin Cancer Res 6(2):347–352

Califano J et al (1996) Genetic progression model for head and neck cancer: implications for field cancerization. Cancer Res 56(11):2488–2492

Braakhuis BJ et al (2002) Second primary tumors and field cancerization in oral and oropharyngeal cancer: molecular techniques provide new insights and definitions. Head Neck 24(2):198–206

Tabor MP et al (2002) Multiple head and neck tumors frequently originate from a single preneoplastic lesion. Am J Pathol 161(3):1051–1060

Bedi GC et al (1996) Multiple head and neck tumors: evidence for a common clonal origin. Cancer Res 56(11):2484–2487

Koukourakis MI et al (2012) Cancer stem cell phenotype relates to radio-chemotherapy outcome in locally advanced squamous cell head-neck cancer. Br J Cancer 106(5):846–853

Yang CC et al (2013) Membrane type 1 matrix metalloproteinase induces an epithelial to mesenchymal transition and cancer stem cell-like properties in SCC9 cells. BMC Cancer 13:171

La Fleur L, Johansson AC, Roberg K (2012) A CD44high/EGFRlow subpopulation within head and neck cancer cell lines shows an epithelial-mesenchymal transition phenotype and resistance to treatment. PLoS One 7(9):e44071

Biddle A, Mackenzie IC (2012) Cancer stem cells and EMT in carcinoma. Cancer metastasis rev 31(1–2):285–293

Chen C et al (2013) Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and cancer stem(-like) cells in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Lett 338(1):47–56

Berx G et al (2007) Pre-EMTing metastasis? Recapitulation of morphogenetic processes in cancer. Clin Exp Metastasis 24(8):587–597

Lee JM et al (2006) The epithelial-mesenchymal transition: new insights in signaling, development, and disease. J Cell Biol 172(7):973–981

Edme N et al (2002) Ras induces NBT-II epithelial cell scattering through the coordinate activities of Rac and MAPK pathways. J Cell Sci 115(12):2591–2601

Lo Muzio L (2001) A possible role for the WNT-1 pathway in oral carcinogenesis. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 12(2):152–165

Boyer B, Valles AM, Edme N (2000) Induction and regulation of epithelial-mesenchymal transitions. Biochem Pharmacol 60(8):1091–1099

O’Sullivan B, Shah J (2003) New TNM staging criteria for head and neck tumors. Semin Surg Oncol 21(1):30–42

Wahi PN et al (1971) Histological typing of oral and oropharyngeal tumours. World Health Organization, Geneva, pp 17–18

da Silva SD et al (2014) TWIST1 is a molecular marker for a poor prognosis in oral cancer and represents a potential therapeutic target. Cancer 120(3):352–362

Kononen J et al (1998) Tissue microarrays for high-throughput molecular profiling of tumor specimens. Nat Med 4(7):844–847

Kokko LL et al (2011) Significance of site-specific prognosis of cancer stem cell marker CD44 in head and neck squamous-cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol 47(6):510–516

Goldman M et al (2013) The UCSC Cancer Genomics Browser: update 2013. Nucl acids res 41(Database issue):D949–954

Hafner C et al (2002) Clonality of multifocal urothelial carcinomas: 10 years of molecular genetic studies. Int J Cancer 101(1):1–6

Mani SA et al (2008) The epithelial-mesenchymal transition generates cells with properties of stem cells. Cell 133(4):704–715

Liu LK et al (2010) Upregulation of vimentin and aberrant expression of E-cadherin/beta-catenin complex in oral squamous cell carcinomas: correlation with the clinicopathological features and patient outcome. Mod pathol 23(2):213–224

Tanaka N et al (2003) Expression of E-cadherin, alpha-catenin, and beta-catenin in the process of lymph node metastasis in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Cancer 89(3):557–563

Tanaka F et al (2013) Snail promotes Cyr61 secretion to prime collective cell migration and form invasive tumor nests in squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Lett 329(2):243–252

Huber GF et al (2011) Down regulation of E-Cadherin (ECAD) - a predictor for occult metastatic disease in sentinel node biopsy of early squamous cell carcinomas of the oral cavity and oropharynx. BMC Cancer 11(217):1–8

Smith A, Teknos TN, Pan Q (2013) Epithelial to mesenchymal transition in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol 49(4):287–292

Ishida K et al (2007) Nuclear localization of beta-catenin involved in precancerous change in oral leukoplakia. Mol Cancer 6:62

Alami J, Williams BR, Yeger H (2003) Differential expression of E-cadherin and beta catenin in primary and metastatic Wilms’s tumours. Mol Pathol 56(4):218–225

Etienne-Manneville S (2008) Polarity proteins in migration and invasion. Oncogene 27(55):6970–6980

Hanken H et al (2014) CCND1 amplification and cyclin D1 immunohistochemical expression in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Clin Oral Invest 18(1):269–276

Klimowicz AC et al (2013) The prognostic impact of a combined carbonic anhydrase IX and Ki67 signature in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Cancer 109(7):1859–1866

Gonzalez-Moles MA et al (2010) Analysis of Ki-67 expression in oral squamous cell carcinoma: why Ki-67 is not a prognostic indicator. Oral Oncol 46(7):525–530

Perisanidis C et al (2012) Evaluation of immunohistochemical expression of p53, p21, p27, cyclin D1, and Ki67 in oral and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. J Oral Pathol Med 41(1):40–46

Pich A, Chiusa L, Navone R (2004) Prognostic relevance of cell proliferation in head and neck tumors. Ann Oncol 15(9):1319–1329

Li L, Bhatia R (2011) Stem cell quiescence. Clin Cancer Res 17(15):4936–4941

Hildebrand LC et al (2014) Spatial distribution of cancer stem cells in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. J Oral Pathol Med 34(1):11–18

Mack B, Gires O (2008) CD44s and CD44v6 expression in head and neck epithelia. PLoS One 3(10):e3360

Georgolios A et al (2006) The role of CD44 adhesion molecule in oral cavity cancer. Exp Oncol 28(2):94–98

Ritchie KE, Nor JE (2013) Perivascular stem cell niche in head and neck cancer. Cancer Lett 338(1):41–46

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP 06/61039-8 and CEPID/FAPESP 98/14335). GBM is supported by the Swiss Cancer League, Effingerstrasse 40, 3001 Bern, Switzerland (BIL KFS-3002-08-2012). The authors would like to acknowledge José Ivanildo Neves, Carlos Ferreira Nascimento, and Severino Ferreira for their technical assistance.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

da Silva, S.D., Morand, G.B., Alobaid, F.A. et al. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) markers have prognostic impact in multiple primary oral squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Exp Metastasis 32, 55–63 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10585-014-9690-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10585-014-9690-1