Abstract

Climate change distress has been shown to be associated with markers of negative mental health. However, it is unclear whether climate change distress is also associated with suicidal ideation and whether this association might be mediated by perceptions of entrapment. On this background, the purpose of the present study was to investigate the association between climate change distress/impairment, entrapment, and suicidal ideation. Participants were recruited at a university in the Ruhr region in Germany. Overall, 323 participants (68.4% female; Mage=26.14, SDage=8.35, range: 18–63 years) filled out self-report questionnaires on climate change distress/impairment, entrapment, and suicidal ideation online. Climate change distress/impairment was significantly positively associated with suicidal ideation. Entrapment completely mediated the association between climate change distress/impairment and suicidal ideation. Results underlines how stressful and existential climate change is experienced by many young persons. Findings underscore the need to develop and evaluate interventions to target climate change distress/impairment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The World Health Organization (i.e., distress and sense of loss due to changes of the home environment; cf., COP24 2020) has identified climate change, including the warming of the global surface temperature, the loss of species, rising oceans and increases in natural disasters (e.g., flooding, draught, storms, wildfires) as a challenge of utmost significance, with substantial threats to life, health, and wellbeing (cf., Watts et al. 2018). Climate change is not only associated with an impact on physical health (Parker et al. 2019; Wu et al. 2022), but also with the risk of increasing prevalence of mental disorders (Cianconi et al. 2020; Clayton 2020; Hrabok et al. 2020; Radua et al. 2024). In line, concerns about climate change have been shown to be associated with markers of negative mental health, such as stress, anxiety, depressiveness, loneliness, worry, hopelessness, guilt, grief, anger and lower perceived longevity (Hajek and König 2022b, 2023; Hickman et al. 2021; Léger-Goodes et al. 2022; Ojala et al. 2021; Wullenkord et al. 2021). On the bright side, concerns about climate change have also been shown to be associated with pro-environmental behavior and environmental activism (e.g., Ogunbode et al. 2022; Whitmarsh et al. 2022; Wullenkord et al. 2021). In consequence, eco-anxiety or climate anxiety, that is anxiety about the consequences and progression of climate change, has become a significant focus of scientific research (Ojala et al. 2021). In a recent study, more than 45% of young adults from ten countries worldwide, stated that concerns about climate change negatively affected their daily lives (Hickman et al. 2021) and about one-quarter of respondents to an U.S. survey state to feel high levels of climate anxiety (American Psychological Association 2020). There are findings showing that distress related to climate change is more common in younger people (Clayton 2020; Hajek and König 2022a) and is more often reported by women than by men (Wullenkord et al. 2021).

It is well known that various major stressors – including the COVID-19 pandemic (Brailovskaia et al. 2021) – can be associated with increased suicidal ideation and behavior (Liu and Miller 2014). Yet, it is unclear in as much climate change distress is associated with suicidal ideation in young adults. There is evidence, that environmental changes caused by climate change (e.g., hotter temperatures, increased drought, air pollution, natural disasters) are associated with heightened suicide and suicide attempt rates (Dumont et al. 2020; Ngu et al. 2021). Furthermore, in a recent study focusing on high school students living in Kenya an association between being worried about climate change and suicidal ideation, suicide plans and lifetime suicide attempts as well as severity of emotional symptoms were found (Ndetei et al. 2024). However, studies on the association between climate change distress and suicidal ideation/behavior are still rare. In principle, suicidal ideation and suicide attempts are prevalent in adolescents (Donath et al. 2019) and young adults (Mortier et al. 2018). Suicidal ideation is a central risk factor for suicide attempts and suicides (Franklin et al. 2017); even though, most people who consider suicide do not show a transition to suicidal behavior (Ribeiro et al. 2016). Still, suicide ideation is highly distressing and represents a mental health outcome in its own right (Jobes and Joiner 2019). Against this background, a first aim of the current study was to investigate the association between climate change distress/impairment and suicidal ideation. Furthermore, it was investigated in as much the association between climate change distress/impairment and suicidal ideation is mediated by perceptions of entrapment.

Entrapment has been defined as a desire to escape from an unbearable situation, tied with the perception that all escape routes are blocked (Gilbert and Allan 1998). Since many young people indicate to feel perplexity and amazement because of adult and political inaction towards climate change (Hickman et al. 2021), perceptions of entrapment might be closely tied to climate change distress. In this sense, Pihkala (2020) emphasizes that uncertainty, uncontrollability and unpredictability are central aspects of eco-anxiety, which might lead to feelings of helplessness, powerlessness and being overwhelmed (see also Pihkala 2022). According to different suicide theories (Galynker 2017; Williams 2001) – including the Integrated Motivational-Volitional Model of Suicide (O’Connor and Kirtley 2018) – entrapment is a core component of the psychological mechanisms underlying suicidal ideation (O’Connor and Portzky 2018). In accord with the theoretical assumption, an association between entrapment and suicidal thoughts has been shown in clinical and non-clinical samples (Forkmann and Teismann 2017; Höller et al. 2022; Siddaway et al. 2015; Taylor et al. 2010), even after statistical control of concurrent risk factors (e.g., depression, hopelessness, suicidal ideation; e.g., O’Connor et al. 2013). Additionally, entrapment has been found to be both a moderator and mediator between risk and protective factors and suicide-related behaviors (e.g., Li et al. 2018; Lucht et al. 2020; Teismann and Forkmann 2017). Still, the association between climate change distress and entrapment has not been studied by now.

Against this background, the aim of the current study was twofold: The first aim was to examine whether climate change distress/impairment is associated with suicidal ideation. The second aim was to examine whether this association is mediated by entrapment.

2 Methods

2.1 Participants

Between May and September 2023, 323 persons (68.4% female; Mage=26.14, SDage=8.35, range: 18–63 years; marital status: 46.7% single, 42.4% with romantic partner, 10.8% married; occupation: 81.7% students, 18.3% employees) participated in a single assessment using an online survey. A lifetime suicide attempt was reported by 33 participants (10.2%) and a suicide attempt within the past four weeks was reported by six participants (1.9%); the average number of lifetime suicide attempts was M = 2.21 (SD = 2.01, range: 1–10) and 98 participants (30.3%) reported some suicidal ideation (SIBS- score ≥ 1) in the last four weeks. All participants were Caucasian.

2.2 Procedure

Data was collected using an anonymous online survey (https://www.unipark.de/). Participants were recruited through flyers distributed at a university in the Ruhr region in Germany as well as postings on the homepage of this university. The study was advertised as an investigation of the association between climate change distress and one’s own well-being (suicidal ideation was not mentioned in the advertisements). In order to take part, participants had to be at least 18 years old and to provide their written consent to study participation by ticking an appropriate box at the beginning of the survey. Prior to assessments, participants were informed about the purpose of the study, the voluntary nature of their participation, data storage and security. The study was approved by the responsible Ethics Committee. Students were compensated by course credits.

2.3 Measures

Suicide Ideation and Behavior Scale (SIBS; Teismann et al. 2021). The SIBS comprises six items assessing suicidal ideation, suicidal intent, suicidal impulses, and suicide planning within the past four weeks. Items are rated on a 6-point Likert-type scale from 0 (never) to 5 (many times a day). Three further items assess the occurrence of a suicide attempt within the last four weeks as well as occurrence/frequency of lifetime suicide attempts. Good internal consistency has been demonstrated in German samples: α = 0.873 (e.g., Teismann et al. 2021). Internal consistency was α = 0.908 in the current sample.

Short Defeat and Entrapment Scale – Entrapment Subscale (SDES; Griffiths et al. 2015; Höller et al. 2020). The entrapment subscale of the SDES comprises four items assessing feelings of being trapped by internal or external causes. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (not at all like me) to 5 (extremely like me). Higher scores indicate stronger feelings of entrapment. The alpha coefficient for the German version of the scale has been found to be good in a non-clinical sample (α = 0.830; Höller et al. 2020) and it was α = 0.861 in the current sample.

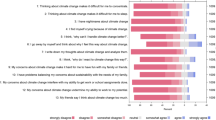

Climate Change Stress and Impairment Scale (CC-DIS; Hepp et al. 2022). The CC-DIS consists of two subscales: The distress subscale comprises 15 items assessing feelings of anger, sadness and anxiety concerning climate change. The impairment subscale comprises eight items assessing general impairment, social impairment and school/work-related impairment associated with climate change. Items are answered on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). Higher scores indicate greater distress/impairment. In the current study a total score, comprising both subscales, was used: α = 0.900.

Depression-Anxiety-Stress Scales 21 – Depression Subscale (DASS-21D; Nilges and Essau 2015). The DASS-21D comprises seven items asking about depression symptoms within the past week. Items are rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale from 0 (did not apply to me at all) to 3 (applied to me very much or most of the time). Psychometric properties of the DASS are well established in both clinical and non-clinical studies (Nilges and Essau 2015). Internal consistency in the current sample was α = 0.913.

2.4 Statistical analyses

We used the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 28 and the macro Process version 4.0 (www.processmacro.org/index.html; Hayes 2021) for statistical analyses. We calculated first descriptive statistics, followed by zero-order bivariate correlation analyses to assess the relationships between the study variables. Furthermore, we ran a partial correlation analysis between climate change distress/impairment and entrapment, as well as between climate change distress/impairment and suicidal ideation, respectively controlling for depression. Next, we calculated a mediation analysis (Process: model 4) that included climate change distress/impairment as a predictor, entrapment as a mediator, and suicidal ideation as the outcome; we included age, gender, and depression as covariates. The basic relationship between climate change distress/impairment and suicidal ideation was denoted by c (the total effect). The path of climate change distress/impairment to entrapment was denoted by a, b denoted the path of entrapment to suicidal ideation. The indirect effect was presented by the combined effect of path a and path b. The direct effect of climate change distress/impairment to suicidal ideation after inclusion of entrapment in the model was denoted by c’. The bootstrapping procedure (10.000 samples) that provides percentile bootstrap confidence intervals (95%CI) assessed the mediation effect. A priori conducted power analyses (G*Power program, version 3.1) revealed that the sample size was sufficient for valid results (power > 0.80, α = 0.05, effect size f2 = 0.15; cf., Mayr et al. 2007).

3 Results

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics and correlations of the assessed variables. The correlation analyses revealed that climate change distress/impairment was significantly positively correlated with entrapment, depression, and suicidal ideation. Entrapment was significantly positively correlated with depression and suicidal ideation. Moreover, there was a significant positive correlation between depression and suicidal ideation (see Table 1). The partial correlation analyses revealed that after controlling for depression, climate change distress/impairment and entrapment, rp = 0.180, p =.001, as well as climate change distress/impairment and entrapment and suicidal ideation, rp = 0.117, p =.036, were still significantly positively correlated.

The mediation model was significant (see Fig. 1). Entrapment significantly mediated the positive relationship between climate change distress/impairment and suicidal ideation when controlling for age, gender, and depression. The basic link between climate change distress/impairment and suicidal ideation was significant (total effect, c: p =.026). The relationship between climate change distress/impairment and entrapment (path a: p =.006), and the link between entrapment and suicidal ideation (path b: p =.001) were also significant. The relationship between climate change distress/impairment and suicidal ideation was no longer significant after the inclusion of entrapment in the model (direct effect, c’: p =.088). The indirect effect was significant, ab: b = 0.007, SE = 0.004, 95% CI [0.001, 0.016].

4 Discussion

The aim of the present study was to examine the association between climate change distress/impairment, entrapment, and suicidal ideation. There were two main findings: (1) Climate change distress/impairment was associated with suicidal ideation in the current sample. (2) Entrapment completely mediated the association between climate change distress/impairment and suicidal ideation.

In line with previous studies (Hajek and König 2022b, 2023; Wullenkord et al. 2021), the current findings demonstrate that climate change distress/impairment is strongly associated with markers of negative mental health. Moreover, an association between climate change distress/impairment and suicidal ideation was established (cf., Ndetei et al. 2024) – even after controlling for concurrent depressive symptoms. This association underlines how stressful and existential climate change is experienced by some of the participants. The present study cannot make any statement about the extent to which climate change distress/impairment is associated not only with suicidal ideation but also with suicidal behavior. However, it should be emphasized that in the vast majority of cases, suicidal thoughts do not turn into suicidal behavior (Ribeiro et al. 2016).

The present study also contributes to the literature on the relationship between entrapment and suicidal ideation (O’Connor and Portzky 2018; Siddaway et al. 2015). In this regard, entrapment was shown to completely mediate the association between climate change distress/impairment and suicidal ideation, pointing to the possibiliy that climate change distress/impairment is relevant to suicidal ideation only when it translates into perceptions of entrapment. The present results support a core assumption of the Integrated Motivational-Volitional (IMV) Model of Suicide (O’Connor and Kirtley 2018), in which entrapment is understood as a crucial mediating factor between stress factors on the one hand and suicidal ideation on the other. Entrapment in the context of suicidal ideation/behaviour is often seen as an irrational and dysfunctional belief associated with stress-related cognitive narrowing (Büscher et al. 2023). However, given what is known about climate change, and the actions needed to attenuate climate change, the impression of being trapped in a hopeless situation is not necessarily an irrational or exaggerated perception of the present life-situation (cf., Cunsolo and Ellis 2018). Climate change awareness confronts individuals with the recognition of general human fragility, it questions the value of human action and human self-worth (Budziszewska and Jonsson 2021); one should therefore refrain from viewing anxiety regarding climate change as an expression of individual pathology. Still, thoughts about being better off dead represent a strong and maladaptive reaction. As such the question arises, how to deal with an existential threat without falling into (individual or collective) denial and disavowal.

A variety of psychological interventions have been proposed to reduce climate change distress, including validation, cognitive behavioral therapy, discouraging self-silencing, encouraging climate change activism and collective action (Baudon and Jachens 2021) as well as cultivating radical hope, i.e. accepting painful realities, without giving up and remaining determined to work towards a better future (Malboeuf-Hurtubise et al. 2024). With regard to the latter especially meaning-focused coping consisting of trust in different societal actors and a capability to switch perspective between worry and hope, has been shown to be associated with reduced anxiety in children and adolescents (Ojala 2012a, b). It is therefore possible that meaning-centered therapy (Chmielewski et al. 2023) could be a viable treatment option regarding climate change distress/impairment. However, the empirical support for most of the interventions mentioned is rather weak; pointing to the necessity to invest in the development and evaluation of intervention studies aimed at reducing climate change distress. Still it has to be emphasized that the experience of climate distress might rather be a sign of integrity than of individual pathology (Budziszewska and Jonsson 2021). Nonetheless, for those who are experiencing suicidal ideation due to climate change distress, attention must be paid to the specific treatment of suicidal thoughts (Gordon 2021).

A major limitation of the current study is its cross-sectional design. Therefore, conclusions on causality have to be handled carefully. Second, since the sample was young, predominately female and 100% Caucasian, it is unclear how the findings would generalize to a more diverse ethnic population. However, young women seem to be most affected by climate change distress/impairment (Clayton 2020; Hajek and König 2022a; Wullenkord et al. 2021), making it a relevant subgroup to focus on. Furthermore, the generalizability of the present findings is limited by the high percentage of students in the current sample and the fact that data were collected in one region in Germany. In future studies, it would be important to include samples from regions that are already more severely affected by the consequences of climate change (e.g., due to flooding or storm surges). Third, only a composite measure of climate change distress/impairment was used in the current study, whereas other conceptualizations such as eco-anxiety, climate anxiety, climate grief, climate anger and/or solastalgia (Coffey et al. 2021), were not investigated in the current study. A more comprehensive measurement of climate-related emotions should be used in future studies. Finally, the current study focused only on associations between climate change distress/impairment and markers of negative mental health, while associations with positive correlates of climate change distress/impairment (e.g., pro-environmental behavior an environmental activism) have not been studied. Corresponding associations have repeatedly been shown (e.g., Ogunbode et al. 2022; Wullenkord et al. 2021) – at least for lower levels of climate anxiety (Whitmarsh et al. 2022); accordingly, it would be interesting to investigate whether entrapment and suicidal ideation as a consequence of climate change distress/impairment have a motivating or a paralyzing effect on pro-environmental behavior.

In sum, the present study underscores that climate change distress/impairment could be associated with depression, entrapment, and suicidal ideation in young people. Furthermore, the present results point to entrapment as a significant psychological pathway connecting stressors and suicidal outcomes.

Data availability

The dataset and further material analysed during the current study will be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

American Psychological Association (2020) Majority of US adults believe climate change is most important issue today. www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2020/02/climate-change. Accessed September 2023 September 2023.

Baudon P, Jachens L (2021) A scoping review of interventions for the treatment of eco-anxiety. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(18):9636. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189636

Brailovskaia J, Teismann T, Friedrich S, Schneider S, Margraf J (2021) Suicide ideation during the COVID-19 outbreak in German university students: comparison with pre-COVID 19 rates. J Affect Disorders Rep 6:100228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadr.2021.100228

Budziszewska M, Jonsson SE (2021) From climate anxiety to climate action: an existential perspective on climate change concerns within psychotherapy. J Humanistic Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167821993243

Büscher R, Sander LB, Nuding M, Baumeister H, Teismann T (2023) Blending video therapy and digital self-help for individuals with suicidal ideation: intervention design and a qualitative study within the development process. JMIR Formative Res 7:e49043. https://doi.org/10.2196/49043

Chmielewski F, Regener R, Margraf J, Schulz S, Teismann T, Hirschfeld G et al (2023) The Scrooge group therapy: a meaning-centered group therapy for outpatients following CBT. J Humanistic Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1177/00221678231172530

Cianconi P, Betrò S, Janiri L (2020) The impact of climate change on mental health: a systematic descriptive review. Front Psychiatry 11:74. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00074

Clayton S (2020) Climate anxiety: psychological responses to climate change. J Anxiety Disord 74:102263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102263

Coffey Y, Bhullar N, Durkin J, Islam MS, Usher K (2021) Understanding eco-anxiety: a systematic scoping review of current literature and identified knowledge gaps. J Clim Change Health 3:100047. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joclim.2021.100047

COP24 (2020) COP24 Special report: health & climate change. https://www.who.int/publications-detail/cop24-special-report-health-climate-change. Accessed September 2023 September 2023

Cunsolo A, Ellis NR (2018) Ecological grief as a mental health response to climate change-related loss. Nat Clim Change 8(4):275–281. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0092-2

Donath C, Bergmann MC, Kliem S, Hillemacher T, Baier D (2019) Epidemiology of suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and direct self-injurious behavior in adolescents with a migration background: a representative study. BMC Pediatr 19(1):1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-019-1404-z

Dumont C, Haase E, Dolber T, Lewis J, Coverdale J (2020) Climate change and risk of completed suicide. J Nerv Ment Dis 208(7):559–565. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000001162

Forkmann T, Teismann T (2017) Entrapment, perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness as predictors of suicide ideation. Psychiatry Res 257:84–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.07.031

Franklin JC, Ribeiro JD, Fox KR, Bentley KH, Kleiman EM, Huang X et al (2017) Risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors: a meta-analysis of 50 years of research. Psychol Bull 143(2):187–232. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000084

Galynker I (2017) The suicidal crisis. Oxford University Press, New York

Gilbert P, Allan S (1998) The role of defeat and entrapment (arrested flight) in depression: an exploration of an evolutionary view. Psychol Med 28(3):585–598

Gordon KH (2021) The suicidal thoughts workbook: CBT skills to reduce emotional pain, increase hope, and prevent suicide. New Harbinger, Oakland

Griffiths AW, Wood AM, Maltby J, Taylor PJ, Panagioti M, Tai S (2015) The development of the short defeat and entrapment scale (SDES). Psychol Assess 27(4):1182–1194. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000110

Hajek A, König H-H (2022a) Climate anxiety in Germany. Public Health 212:89–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2022.09.007

Hajek A, König H-H (2022b) Climate anxiety, loneliness and perceived social isolation. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(22):14991. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192214991

Hajek A, König H-H (2023) Do individuals with high climate anxiety believe that they will die earlier? First evidence from Germany. Int J Environ Res Public Health 20(6):5064. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20065064

Hayes AF (2021) Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis, 2nd edn. The Guilford Press, New York

Hepp J, Klein SA, Horsten LK, Urbild J, Lane SP (2022) The climate change distress and impairment scale: introduction of the measure and first findings on pro-environmental behavior. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-1986606/v1

Hickman C, Marks E, Pihkala P, Clayton S, Lewandowski RE, Mayall EE et al (2021) Climate anxiety in children and young people and their beliefs about government responses to climate change: a global survey. Lancet Planet Health 5(12):e863–e873. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00278-3

Höller I, Teismann T, Cwik JC, Glaesmer H, Spangenberg L, Hallensleben N et al (2020) Short defeat and entrapment scale: a psychometric investigation in three German samples. Compr Psychiatr 98:152–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2020.152160

Höller I, Rath D, Teismann T, Glaesmer H, Lucht L, Paashaus L et al (2022) Defeat, entrapment, and suicidal ideation: twelve-month trajectories. Suicide Life‐Threatening Behav 52(1):69–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12777

Hrabok M, Delorme A, Agyapong VIO (2020) Threats to mental health and well-being associated with climate change. J Anxiety Disord 76:102295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102295

Jobes DA, Joiner TE (2019) Reflections on suicidal ideation. 40(4):227–230. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000615

Léger-Goodes T, Malboeuf-Hurtubise C, Mastine T, Généreux M, Paradis P-O, Camden C (2022) Eco-anxiety in children: a scoping review of the mental health impacts of the awareness of climate change. Front Psychol 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.872544

Li S, Yaseen ZS, Kim H-J, Briggs J, Duffy M, Frechette-Hagan A et al (2018) Entrapment as a mediator of suicide crises. BMC Psychiatry 18(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1587-0

Liu RT, Miller I (2014) Life events and suicidal ideation and behavior: a systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev 34(3):181–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2014.01.006

Lucht L, Höller I, Forkmann T, Teismann T, Schönfelder A, Rath D et al (2020) Validation of the motivational phase of the integrated motivational–volitional model of suicidal behavior in a German high-risk sample. J Affect Disord 274:871–879. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.079

Malboeuf-Hurtubise C, Léger-Goodes T, Herba CM, Bélanger N, Smith J, Marks E (2024) Meaning making and fostering radical hope: applying positive psychology to eco-anxiety research in youth. Front Child Adolesc Psychiatry 3:1296446. https://doi.org/10.3389/frcha.2024.1296446

Mayr S, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Faul F (2007) A short tutorial of GPower. Tutorials Quant Methods Psychol 3(2):51–59. https://doi.org/10.20982/tqmp.03.2.p051

Mortier P, Cuijpers P, Kiekens G, Auerbach RP, Demyttenaere K, Green JG et al (2018) The prevalence of suicidal thoughts and behaviours among college students: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med 48(4):554–565. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291717002215

Ndetei DM, Wasserman D, Mutiso V, Shanley JR, Musyimi C, Nyamai P et al (2024) The perceived impact of climate change on mental health and suicidality in Kenyan high school students. BMC Psychiatry 24(1):117. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-024-05568-8

Ngu FF, Kelman I, Chambers J, Ayeb-Karlsson S (2021) Correlating heatwaves and relative humidity with suicide (fatal intentional self-harm). Sci Rep 11(1):22175. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-01448-3

Nilges P, Essau C (2015) Die Depressions-Angst-Stress-Skalen. Der Schmerz 29(6):649–657. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00482-015-0019-z

O’Connor RC, Kirtley OJ (2018) The integrated motivational–volitional model of suicidal behaviour. Philosophical Trans Royal Soc B: Biol Sci 373(1754):20170268. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2017.0268

O’Connor RC, Smyth R, Ferguson E, Ryan C, Williams JMG (2013) Psychological processes and repeat suicidal behavior: a four-year prospective study. J Consult Clin Psychol 81(6):1137–1143. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033751

O’Connor RC, Portzky G (2018) The relationship between entrapment and suicidal behavior through the lens of the integrated motivational–volitional model of suicidal behavior. Curr Opin Psychol 22:12–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.07.021

Ogunbode CA, Doran R, Hanss D, Ojala M, Salmela-Aro K, van den Broek KL et al (2022) Climate anxiety, pro-environmental action and wellbeing: antecedents and outcomes of negative emotional responses to climate change in 28 countries. J Environ Psychol 84(1):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2022.101887

Ojala M (2012a) Hope and climate change: the importance of hope for environmental engagement among young people. Environ Educ Res 18(5):625–642. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2011.637157

Ojala M (2012b) Regulating worry, promoting hope: how do children, adolescents, and young adults cope with climate change? Int J Environ Sci Educ 7(4):537–561

Ojala M, Cunsolo A, Ogunbode CA, Middleton J (2021) Anxiety, worry, and grief in a time of environmental and climate crisis: a narrative review. Annu Rev Environ Resour 46:35–58. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-012220-022716

Parker CL, Wellbery CE, Mueller M (2019) The changing climate: managing health impacts. Am Family Phys 100(10):618–626

Pihkala P (2020) Anxiety and the ecological crisis: an analysis of eco-anxiety and climate anxiety. Sustainability 12(19):7836. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12197836

Pihkala P (2022) Toward a taxonomy of climate emotions. Front Clim 3:738154. https://doi.org/10.3389/fclim.2021.738154

Radua J, De Prisco M, Oliva V, Fico G, Vieta E, Fusar-Poli P (2024) Impact of air pollution and climate change on mental health outcomes: an umbrella review of global evidence. World Psychiatry 23(2):244–256. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.21219

Ribeiro JD, Franklin JC, Fox KR, Bentley KH, Kleiman EM, Chang BP et al (2016) Self-injurious thoughts and behaviors as risk factors for future suicide ideation, attempts, and death: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol Med 46(2):225–236. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291715001804

Siddaway AP, Taylor PJ, Wood AM, Schulz J (2015) A meta-analysis of perceptions of defeat and entrapment in depression, anxiety problems, posttraumatic stress disorder, and suicidality. J Affect Disord 184:149–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.05.046

Taylor PJ, Gooding PA, Wood AM, Johnson J, Pratt D, Tarrier N (2010) Defeat and entrapment in schizophrenia: the relationship with suicidal ideation and positive psychotic symptoms. Psychiatry Res 178(2):244–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2009.10.015

Teismann T, Forkmann T (2017) Rumination, entrapment and suicide ideation: a mediational model. Clin Psychol Psychother 24(1):226–234. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.1999

Teismann T, Forkmann T, Glaesmer H, Juckel G, Cwik JC (2021) Skala Suizidales Erleben Und Verhalten (SSEV). Diagnostica 67(3):115–125. https://doi.org/10.1026/0012-1924/a000269

Watts N, Amann M, Ayeb-Karlsson S, Belesova K, Bouley T, Boykoff M et al (2018) The Lancet countdown on health and climate change: from 25 years of inaction to a global transformation for public health. Lancet 391(10120):581–630. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32464-9

Whitmarsh L, Player L, Jiongco A, James M, Williams M, Marks E et al (2022) Climate anxiety: what predicts it and how is it related to climate action? J Environ Psychol 83:101866. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2022.101866

Williams M (2001) Suicide and attempted suicide. Penguin Books, London

Wu Y, Li S, Zhao Q, Wen B, Gasparrini A, Tong S et al (2022) Global, regional, and national burden of mortality associated with short-term temperature variability from 2000–19: a three-stage modelling study. Lancet Planet Health 6(5):e410–e421. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(22)00073-0

Wullenkord MC, Tröger J, Hamann KRS, Loy LS, Reese G (2021) Anxiety and climate change: a validation of the climate anxiety scale in a German-speaking quota sample and an investigation of psychological correlates. Clim Change 168(20):1–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-021-03234-6

Acknowledgements

The present work was endorsed by DZPG (German Center for Mental Health).

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

The responsible Ethics Committees approved the present study and the study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

All participants give their consent to participation at the beginning of the study. Prior to assessments, participants were informed about the purpose of the study, the voluntary nature of their participation, data storage and security. They gave written informed consent before participating.

Consent for publication

All participants were properly instructed that data gained in the present study will be used for publication in an anonymous form and gave online their informed consent for publication.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Competing interests

None.

Financial interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Brailovskaia, J., Teismann, T. Climate change distress, entrapment, and suicidal ideation. Climatic Change 177, 127 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-024-03784-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-024-03784-5