Abstract

This study examines the interactions between local air pollutants and greenhouse gas emissions to assess potential synergies and trade-offs between local environmental pollution and climate policies, using the power generation sector in Brazil under different carbon scenarios up to 2050 as a case study. To this end, an integrated approach was developed, combining energy scenarios under different carbon mitigation targets and a local air pollution assessment model, tailored to the context of the Brazilian power sector. Results reveal that there are deep interactions between climate change mitigation and local air pollution abatement strategies. Increasing the diffusion of low-carbon technologies results in both mitigation of climate change and lower terrestrial acidification potential impacts, due to the rapid phase-out of fossil fuel power technologies. However, local air pollution indicators for particulate matter formation and human toxicity may rise in response to greenhouse gas emission mitigation constraints, indicating the existence of potential trade-offs. Some of these trade-offs can be offset by introducing available end-of-pipe pollution control measures reinforced by dedicated air quality policies.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Effective actions are required to accelerate the pace of global responses to halt climate change and its threats to global sustainability (Rogelj et al. 2016). While there may be costs to climate change mitigation, policies that simultaneously tackle greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and promote local air quality co-benefits can induce cost savings (Rafaj et al. 2013). Although climate change and local air pollution (LAP) are usually addressed separately by policymakers, GHG emissions and local air pollutants have common sources and interact in the atmosphere, causing a series of interconnected effects on the environment at local, regional and global scales (Thambiran and Diab 2011).

Thus, when tackling climate change, low-carbon policies may achieve two goals at once, by simultaneously contributing to climate change mitigation, while promoting better air quality in urban areas. At the same time, the cost of abatement technologies for local air pollutants may decrease if they are integrated with climate policies (van Harmelen et al. 2002). In fact, both problems are related to economic development and are driven by the current patterns of energy production and consumption and existing policy setups (Rafaj et al. 2014).

Several studies on co-benefits of GHG mitigation policies at the global level have been undertaken. There is a general consensus among studies for both developed and developing countries that there are additional benefits from mitigation of GHG emissions in terms of improved air quality (Bollen 2015; Klausbruckner et al. 2016; Puppim de Oliveira and Doll 2016; Rao et al. 2017; West et al. 2013). For instance, Rao et al. (2017) developed different air pollution narratives under the global Shared Socio-economic Pathway (SSP) framework, concluding that scenarios with limited climate change mitigation present higher air pollution impacts than scenarios with more stringent carbon mitigation trajectories. However, environmental assessments on renewables, carbon capture and storage (CCS) and conventional fossil fuel power generation technologies address the local impacts of air pollution from a global perspective (Castelo Branco et al. 2013; Hertwich 2013). Therefore, these studies do not integrate regional energy scenarios to investigate the implications of integrated climate and LAP policy strategies at the national level.

In Brazil, little attention has been paid to these issues, with a few exceptions. Schaeffer and Szklo (2001) analysed the expansion of the Brazilian power sector up to 2020. The authors concluded that, depending on how priorities are set, conflicts between LAP and global climate issues may arise. While relevant to the field, the authors applied a simple power-sector-only least-cost optimisation model based on generic emission factors, without considering the implementation of LAP abatement technologies, to assess energy scenarios and their implications for both climate and LAP strategies.

This study presents a new framework for examining interactions between LAP and GHG emissions from national or regional power generation sectors under different carbon scenarios up to 2050, allowing the comparison of linkages between climate mitigation policies and stringent air pollution control strategies. To this end, an integrated approach was developed, combining a set of optimised climate mitigation energy scenarios with a LAP assessment model. This approach can be applied to any region or country or even globally. As a case study, we tailored it to the context of the Brazilian power sector. To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first attempt to evaluate, at the national level, the interactions of climate policies and LAP control strategies in the Brazilian power sector. Furthermore, results presented here are relevant to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) adopted by the United Nations in 2015, particularly those related to local air pollution (SDG 3 on “Good health” and SDG 11 on “Sustainable cities and communities”) (UN 2015). Although this paper focuses on a case study for Brazil, this research provides evidence that climate and development goals need to be assessed in an integrated manner to tease out trade-offs and synergies between the Paris Agreement and the SDGs. While the current framework has been applied to Brazil, global conclusions in terms of linkages between climate and LAP goals of low-carbon technologies, such as renewables and CCS, can be drawn.

2 Material and methods

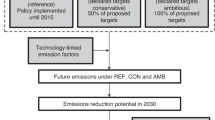

To assess the potential synergies and trade-offs of climate policies and LAP, the present research is organised in three methodological stages, as shown in Fig. 1, entailing (i) selection of optimal power supply portfolios under different carbon restrictions from previous studies, (ii) evaluation of GHG emissions and (iii) quantification of LAP indicators.

2.1 Power supply scenarios

The methodology begins with exogenous energy systems scenarios that achieve certain emissions or radiative forcing targets. For the case of Brazil, model version COPPE-MSB v1.3.1 was used to generate the climate mitigation scenarios described in Koberle et al. (2015), which represent least-cost pathways for the evolution of the Brazilian power sector. These exogenous results served as inputs for the air pollution computation, through which LAP co-benefits were assessed. Mitigation scenarios include efforts associated with the Brazilian Nationally Determined Contribution – NDC (LC0 scenario), as well as an enhanced ambition to cope with the global effort to keep average temperature rise below 2 °C relative to pre-industrial era (LC100 scenario).

The two climate mitigation scenarios here explored are, then, compared to a baseline scenario, which reflects current trends for the Brazilian energy system. This scenario excludes carbon emission prices, as well as technological options for improved energy efficiency (Szklo et al. 2017). This attempts to represent the current situation in Brazil, whereby such technologies are not introduced due to typical barriers to energy efficiency measures, such as market and institutional failures.Footnote 1

In the low-carbon (LC) scenarios the model is allowed to run with the full range of technological innovation options. As the result of energy efficiency measures with negative costs, electricity demand is lower in all LC scenarios. The LC0 scenario assumes a carbon price equal to zero, so that only non-regret measures, such as improvements in energy efficiency,Footnote 2 are adopted. As demonstrated by Koberle et al. (2015), the LC0 scenario delivers most of the energy sector targets included in the Brazilian NDC (GoB 2015) pledged under the Paris Agreement goals (COP21).

The LC100 scenario introduces a carbon price of $100/tCO2e, bringing about deeper changes in the structure of the power sector. Particularly noteworthy is the removal of sub-critical pulverised coal power plants and the introduction of sugarcane bagasse-fired power plants and coal power plants with carbon capture and storage (CCS). Figure 2 shows the power system technologies deployed in the baseline and climate policy scenarios.

It is important to note that these scenarios are not the result of the present study, but the starting point from which the LAP assessment is carried out. For more details on the scenarios and their relation to the Brazilian NDC, the reader is referred to Koberle et al. (2015)Footnote 3 and Supplementary Materials.

One of the limitations of this study relates to the structure of the COPPE-MSB model. It is a very detailed, both temporally and spatially, perfect-foresight cost optimisation model. The model gives the lower overall system cost solution, subject to the restrictions imposed (e.g. attending demand, resource availability, and operational constraints) and according to inputted techno-economic assumptions (see Supplementary Materials). Although the model assumes a perfect market competition, something rarely observed in complex human economic systems, constraints were used to mimic market failures wherever applicable. Also, as cost-minimisation is an explicit goal of energy policy in Brazil (as highlighted by the auctions system for new power generation capacity), the model solution is a realistic representation of a desired goal. Baseline results indicating the expansion of coal power capacity in Brazil may be particularly controversial, but coal is, indeed, the marginal cost plant in the absence of any environmental constraints, a condition the baseline scenario is designed to capture. At the same time, it is noted that the additional costs for installing pollution controls as well as potential efficiency losses to the power supply technologies are not explicitly accounted for in the COPPE-MSB model. Indeed, adding these costs to the optimization would not allow testing the co-benefits that climate policy, by itself, could have in terms of LAP reduction from a least-cost baseline.

2.2 Environmental assessment of power generation technologies

In this study, an inventory of GHG and LAP emissions was developed to assess the contribution of the power sector to climate change and air quality impacts in Brazil. The selected baseline year is 2010 and projections were made up to 2050. Results have been validated for the baseline year 2010 based on the Third National Communication of Brazil to the United Nations Framework Convention of Climate Change (MCTI 2016).

The analysis focuses on available/conventional generation technologies currently used and likely to be implemented in the power sector. Advanced low-carbon technologies, which are yet to become available at a commercial scale but that might be cost-competitive under high carbon price scenarios, are also considered. The available options encompass 24 fossil-based, renewable-based and CCS technologies.

The system boundaries of the LAP analysis only comprise direct emissions of downstream processes, i.e. the operation of power plants to generate electricity in grid-connected and isolated systems. Thus, upstream activities have been excluded from the analysis. Although the evaluation of the entire life cycle of power generation systems is essential to measure the overall environmental impacts of the power sector, as highlighted by Portugal Pereira et al. (2014); Portugal-Pereira et al. (2016), this work compares impacts of climate mitigation scenarios on LAP. Thus, including life cycle impacts of power generation scenarios would increase the “noise” of results, while bringing limited added value to the analysis of LAP/climate change linkages. Further details about life cycle implications of future energy scenarios in Brazil are reported by Portugal-Pereira et al. (2016).

The inventory assessed three GHGs and 19 airborne pollutants. The emissions of carbon and sulphur dioxides (CO2 and SO2) in uncontrolled facilities are constrained mainly by fuel properties, being proportional to carbon and sulphur contents in the fuel and net conversion efficiency (EPE 2007; IPCC 2006). The equation to estimate the CO2 emission factor is displayed in Eq. 1. It assumes that CO2 emissions are equal to the difference between the total emissions emitted if fuel was fully oxidised into CO2 and the carbon emitted in the form of CO, CH4 and non-methanogenic volatile compounds (NMVOC).

Eq. 1 Estimation of CO2 emissions(gCO2/kWhe)

where EFCO2,f,y is the emission of CO2 in g per generated kWhe of fuel f combusted with technology t in the year y, C f is the carbon content of fuel f (kg/GJ) (IPCC 2006), η t (%) is the conversion efficiency of technology t in the year y, EFCO, EFCH4 and EFNMVOC (g/kWhe) refer to the emission factor of carbon monoxide, methane, and non-methanogenic volatile compounds, respectively, MCO2 is the molar mass of CO2 (44.0095 g/mol) and AC is the atomic mass of carbon (12.0107 g/mol).

Similarly, the emission factor for SO2 assumes that fuels are fully oxidised and sulphur content is emitted as SO2 with no retention in ashes and no desulphurising control (Eq. 2).

Eq. 2 Estimation of SO2 emissions (gSO2.kWhe) (gSO2/kWhe)

Where EFSO2,f,y is the emission of SO2 in g per generated kWhe of fuel f combusted with technology t in the year y, S f is the sulphur content of fuel f (kg/GJ), η t (%) is the conversion efficiency of technology t in the year y, MSO2 refers to the molar mass of SO2 (64.0638 g/mol) and AS is the atomic mass of sulphur (32.0650 g/mol).

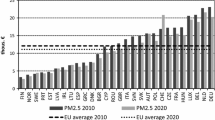

As for other airborne pollutants (PM10, NO x , SO2, etc.), specific emission factors were compiled for representative combustion technologies extrapolated from national guidelines and emission control standards in Brazil and the database of EMEPCONNAIR standards (EEA 2013). The emission factors calculated and estimated in this work are presented in the Supplementary Materials.

Airborne pollutants were aggregated into mid-point indicators through characterisation factors, which reflect the relative influence of inventory output flows (i.e. the emission levels of a given pollutant) for a common or similar environmental burden (e.g. acidification potential) within the cause-effect chain (Eq. 3). In this study, the selected impact categories include: climate change, measured as CO2e; particulate matter formation potential (PMF), as PM10e; terrestrial acidification potential (TAP), in SO2e; and human toxicity (HT), in 1,4-Diethylbenzene equivalent (1–4-DBe). The characterisation factors for LAP impacts derive from an adaptation of the ReCiPe method following mid-point impact categories (Goedkoop et al. 2008). As for climate change impacts, the GHG’s GWPFootnote 4 factors were selected from the IPCC AR5 report (Myhre et al. 2013) in a 100-year timeframe. The Supplementary Materials show the characterisation factors of each assessed impact.

Eq. 3 Estimation of mid-point indicators according to ReCiPe method

Where IMid-point refers to the assessed impact, EF i is the emission factor and F i expresses the characterisation factor of pollutant i for the selected impact.

Conventional fossil fuel thermal power plants are the main contributors to the impacts assessed here, with elevated amounts of emissions per unit of power generated (Table 1). Among fossil fuel technologies, the pulverised coal options were the largest contributors to climate change and human toxicity, followed by diesel and HFO, since these fuels have high carbon contents. These fossil fuel technologies also induce impacts on TAP and PMF if no control technologies are applied. Natural gas power plants, on the other hand, are the least impactful among fossil fuel technologies, with negligible direct emissions of sulphur dioxide (SO2) and limited nitrogen oxides (NO x ), particulates and mercury (Hg). Also, their GHG emissions are nearly half of conventional pulverised coal technologies per unit of electricity generated.

Biomass power plants have negligible impacts on GHG emissions as the direct CO2 emitted during the combustion of biomass is from biogenic sources, therefore assumed to be null. Nonetheless, biomass power plants without air pollution control technologies cause large impacts in terms of PMF and HT loads, comparable to conventional diesel and HFO technologies.

Although plants equipped with CCS facilities reduce climate change impacts significantly, leading to a reduction of up to 82–88% of end-of-pipe CO2e emissions, 36–55% of SO2e emissions and 8–37% of PM10e emissions, this technology results in an energy penalty, as it requires additional consumption of fuel and consequently emits supplementary GHG emissions per kWh generated (Castelo Branco et al. 2013). Despite the assumption that these plants are equipped with pollution controls, in terms of overall impacts on LAP this technology outcomes are limited due to the energy penalties. Furthermore, these technologies result in 14–76% higher impacts of HT than conventional technologies.

Non-biomass renewable technologies have null direct impacts during their operation, as they have no direct emission of air pollutants. Although hydropower plants with large reservoirs in tropical environments may emit considerable amounts of methane due to significant flooding of organic matter that decays under anaerobic conditions (IEA 2012), methane concentration varies widely with type of vegetation flooded, passage of time and external variables, such as temperature, inflow rate, wind, water depth and oxygen content (Hertwich 2013). For this reason, direct impacts of hydropower plants were not considered in this study.

Direct impacts of nuclear power operation are also negligible, because end-of-pipe emissions of enriched uranium fission and steam turbines are limited. Nevertheless, nuclear power technologies might be extremely impactful on human health, mainly during decommission procedures and the treatment of nuclear residues, which exceed human time scales (Portugal-Pereira and Esteban 2014).

2.2.1 LAP abatement through end-of-pipe control measures

The performance of power plants in terms of TAP and PMF can be improved by the addition of emission controls commercially available today, such as filters and precipitators. However, such measures have costs and were not included in the original scenarios of Koberle et al. (2015). Their inclusion would have changed the investment cost of the technologies assessed and, thus, the model’s cost-optimal solution. Therefore, the baseline reflects the least-cost configuration for the power system so as to test the effect that climate policy, by itself, could have on LAP emissions.

Currently, there are abatement technologies put in place to some extent in existing Brazilian power plants, since there are federal and state level environmental regulations to constrain the emission levels of SO2 and PM pollutants (CONAMA Resolution No. 8/1990 and No. 436/2011). However, to the authors’ knowledge and according to a survey conducted with local experts, the enforcement of air quality regulations is inadequate in the country. For this reason, the existing measures do not achieve the expected removal rates, and in many cases, they are installed but not fully operated.

In the future, plants are expected to have tighter emission abatement requirements, reinforced by more stringent legislation. However, given the uncertain policy panorama of Brazil, this assumption is not straightforward, since most of the control technologies require additional costs and investments in monitoring infrastructure. For this reason, two scenario variants for LAP controls were considered assuming (i) no control of SO2, NO x and PM10, and (ii) stringent control of pollutants with the most efficient technologies adopted for all power plant capacity installed after 2030. Characteristics of the LAP abatement measures have been extracted from the GAINS model (IIASA 2016) and the assumed removal rates are shown in Table 2.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 GHG emissions

Figure 3 illustrates the GHG emissions from power generation scenarios, showing that in the absence of climate policies, power sector GHG emissions would increase fourfold, rising from 36 MtCO2e in 2010 to 157 MtCO2e in 2050. The likely saturation of hydropower potential outside the Amazon region implies the current hydro/bagasse power generation mix may have limited potential to fulfil steadily rising future electricity demand. Deploying new coal thermal power plants emerges as a least-cost option to fill the gap, so that, if realised, by 2050, coal-based power would contribute to 89% (141 MtCO2e) of the sector’s GHG emissions, followed by NG technologies (9%) (14 MtCO2e). Nuclear and renewable energy sources, on the other hand, have no direct GHG emissions. These findings are in line with previous analyses of energy sector impacts on climate change in Brazil (Lima et al. 2015; Lucena et al. 2015; Portugal-Pereira et al. 2016). Although Brazil does not have an updated governmental Energy Strategy up to 2050, under the government’s 10-year Strategic Energy Plan there is indication for 10.5 GW expansion of NG and coal thermal power plant capacity (EPE 2015).

In the LC0 scenario, which delivers most of the Brazilian NDC targets, the power sector emits 84 MtCO2e in 2050, which means a reduction of 46% when compared to the baseline scenario, despite a doubling of demand compared to 2010 levels. Under this scenario, non-regret measures are implemented, including capacity expansion of bagasse thermal power plants as well as wind turbines. This scenario to some extent reflects the Brazilian NDC’s proposed expansion of the share of non-hydro renewables in power generation to at least 23% of total installed capacity by 2030 (GoB 2015).

Under a stringent climate policy scenario (LC100) carbon prices reaching $100 per tonne of CO2e in 2050 bring emissions down to 18 MtCO2e. Here, the least-cost solution introduces coal power with CCS and an expansion of bagasse power plant capacity, drastically reducing GHG emissions. It is important to note that this ambition will remain unlikely if Brazil maintains its present energy trajectory, based on least-cost generation technologies regardless of environmental externalities. Power generation technologies with higher LCOE than conventional ones are not the top priority in the domestic energy agenda, delaying introduction of innovative low-carbon technologies such as CCS and biomass with CCS (BECCS) which are not yet mature or tested at scale.

3.2 Local air pollution

Figure 4 shows LAP impacts (measured as TAP, PMF and HT) in the baseline and climate mitigation scenarios, with and without end-of-pipe abatement technologies—the control scenario variants. The figure shows that the need for deployment of LAP abatement technologies varies according to the GHG mitigation target scenario, indicating interlinkages between climate mitigation and LAP.

In the case of TAP, these interlinkages are synergistic, since climate policies reduce SO2e emissions, the main indicator of terrestrial acidification potential (Fig. 4a), suggesting low-carbon technologies result in mitigation of both climate change and TAP. In 2050, in the LC0 and LC100 scenarios, SO2e emissions reach 71 and 41% of baseline scenario levels, respectively. This is a direct result of drastically lower use of coal-fired power in these scenarios.

Regarding PMF and HT impact categories, on the other hand, results show limited co-benefits (Figure 4b, c). While CCS facilities significantly reduce CO2 and SO2 emissions, these facilities have an energy penalty and require larger amounts of fuel per kWh delivered, which results in higher emissions of particulates when compared to conventional technologies. Also, bagasse power plants have higher particulate matter emissions than coal per unit of power generated, so that their increasing participation in climate mitigation scenarios imply more severe impacts in PMF category if no additional control measures are introduced. Therefore, the scenarios pursuing only climate mitigation result in higher LAP impacts in the PMF category, which is 13–23% higher than in the baseline scenario, while HT is mitigated by only 11–28%, depending on the mitigation scenario.

Summarising, since TAP emissions are reduced in both GHG scenarios, it follows that the cost of mitigating SO2 emissions will be lower in these scenarios. On the other hand, since PM formation increases in the mitigation scenarios, a likely rise in the cost of particulate matter emissions abatement is expected for the system as a whole.

LAP impacts can be mitigated through adoption of end-of-pipe abatement technologies, which can drastically reduce SO2e and PM10e emissions from coal and biomass plants. This is simulated in the control scenario variants for TAP and PMF (Fig. 4a, b). For the baseline, the potential for emission reductions is about 90% for SO2e and 94% for PM10e in 2050. In the climate mitigation scenarios, the need for deployment of LAP abatement technologies varies according to the GHG mitigation target scenario and the LAP category considered, being lower for TAP but higher for PMF. Policy framework and market failures prevent significant deployment of LAP abatement technologies in Brazil to date.

3.3 Climate change and local air pollution synergies and trade-offs

The findings of this study are consistent with the hypothesis that climate policies can generate co-benefits in terms of air quality in Brazil, mainly due to an increased share of non-combustible renewables. Regarding LAP, carbon pricing may have distinct consequences depending on the impact category considered. Since local air pollutants considered in this study cause damage to human and natural systems, the climate mitigation alternatives evaluated could potentially generate benefits in terms of human health and local environment. However, findings also reveal trade-offs involving some of the low-carbon technologies. In particular, sugarcane bagasse combustion and CCS solutions—if no LAP abatement measures are applied by 2050—may increase some LAP impact categories despite reducing GHG emissions.

Potential co-benefits from energy efficiency gains and from increased shares of non-combustible renewables are clearly observed in all impact categories, and are favoured by higher carbon prices. As mentioned, non-combustible technologies have null direct emissions and are thus favoured by the fact that this study does not include life cycle emissions. For bagasse combustion and CCS facilities, clear benefits exist for TAP and, to a limited extent, for HT. Bagasse has reduced sulphur content, which directly results in lower SO2 emissions, a major contributor to TAP. For technical reasons involving separation membrane affinity to sulphur compounds, CCS technologies require sulphur removal before CO2 capture, which also brings about reductions in TAP.

In addition to the benefits, there are also trade-offs involved between climate change mitigation and LAP. The most obvious interchange involves the increase of PMF in the GHG mitigation scenarios due to higher penetration of biomass combustion generation technologies (mainly sugarcane bagasse). Bagasse combustion generates almost twice as much particulate matter per unit of power generated than coal combustion, if no post-combustion PM-control measures are introduced. However, as shown by the control scenario analysis, this trade-off could be offset by implementing control measures in new plants and retrofitting existing ones, although the capital costs and energy penalties involved may pose a challenge to the ethanol-producing sector. Finally, present-day impacts of Brazilian bagasse power plants are limited by the fact that they are mainly installed in ethanol distilleries and sugar mills, which are usually small-scale, geographically dispersed and located far from densely populated areas, although it may be risky to assume this will always be the case.

Although CCS also requires the removal of PM for technical reasons, CCS is neutral in overall balance for the PMF impact category because of the 43% energy penalty involved in carbon capture, which causes an increase in the amount of fuel burned, offsetting the benefit of the PM removal process. This increased fuel consumption caused by CCS also results in higher emissions of 1.4-DBe, implying higher HT impacts, when compared to the baseline trend. Emissions of 1.4-DBe increase by 76% for domestic coal, 14% for imported coal and 27% for bagasse (Table 1).

Concerning LAP control mechanisms, the presence of both synergies and trade-offs, as explained in Section 3.2, means the abatement of GHGs, TAP and PMF requires a tailored policy approach addressing all these environmental domains in parallel. The results reinforce the need for an integrated analysis of climate and local air pollution abatement and a tailored study to this end—quantifying the full impacts on the costs and human health—should be undertaken in the future.

Overall, there are significant synergies between climate change mitigation and LAP abatement in the power sector in Brazil. Since LAP impacts are local and short-term, LAP abatement measures could serve as additional incentives for the country to adopt more stringent GHG emission mitigation efforts. Globally, because of differences in the temporal and spatial scales of climate change and LAP, the co-benefits occur earlier and closer to where the climate policies were adopted. This serves as motivation for addressing these issues in an integrated way. For this reason, LAP abatement should be strengthened and systematically incorporated in the development and low-carbon policies. This could actually accelerate the implementation of the strategy indicated in the Brazilian NDC to reduce GHG emissions by 43% below 2005 levels by 2030, by incorporating 45% of renewable sources in the energy sector and by improving energy efficiency by 10% by 2030 (GoB 2015). In the same line, the linkage between climate change and LAP could strengthen the enactment of the SDGs in Brazil, particularly the ones related to climate change and air pollution. This interplay between climate change and the other SDGs is particularly important, since there are interdependencies between the different SDGs, among which energy access and pollution abatement are of particular significance for Brazil.

3.4 Implications beyond the Brazilian power-sector case study

Global and local environmental protection goals need to be included in the political agenda, along with other development priorities, to guarantee the implementation of policies to deliver the pledges made by the parties in the Paris Agreement and to meet the goals of the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. This study shows that an integrated assessment helps understanding the multiple benefits and potential trade-offs that might occur when implementing climate policies in power generation, in particular, and in the energy sector as a whole. An increased share of non-combustible renewables and energy efficiency measures result in significant air quality and human health benefits. This pattern is expected to be robust across all regions under decarbonization regimes. However, we also highlighted potential trade-offs when expanding bioenergy sources and CCS technologies, if no additional LAP abatement technologies are implemented—and again, this finding is not Brazil-specific and has to be considered by policymakers in general when assessing the impacts of deep cuts in GHG emissions.

The increasing share of wind and solar PV in the power generation mix has clear co-benefits in improving air quality and human health in all regions relying on fossil-/coal-fired technologies, as the direct impacts of non-combustible renewables on LAP are null. Nonetheless, as stated earlier, a fully integrated assessment, which considers the indirect impacts through the entire life cycle of material and infrastructure construction, should also be conducted to ensure the effective mitigation of impacts along the whole chain of electricity production technologies. Significant benefits are also found in energy efficiency improvements, as they result in reductions of final energy consumption and their associated emissions. However, future studies should clarify the implications of rebound effects in reducing or amplifying the benefits of energy efficiency interventions.

Potential trade-offs in some LAP indicators are observed in expanding bioenergy sources, which is a feature present in numerous national strategies to mitigate carbon emissions. While biomass resources can reduce the sulphur intensity of the fuel mix, which directly results in lower SO2 emissions and TAP impacts, biomass combustion technologies tend to generate high levels of particulate matter, that are known to be among the most dangerous stressors for human health globally. Therefore, bioenergy expansion must be associated with effective implementation of post-combustion PM-control measures. This may be a challenge, particularly in developing countries, given the high capital costs and energy penalties involved. CCS technologies also encompass potential trade-offs in terms of human health. Although CCS implies in sulphur and PM removal before CO2 capture, CCS units typically involve high energy penalties. Thus, to produce the same amount of energy, larger amounts of primary energy are required, potentially resulting in higher emissions of 1.4-DBe and higher HT impacts.

Globally, there are synergies between climate change mitigation and LAP abatement in the energy sector that, if properly monetized, could offset some of the costs of climate change mitigation and become an additional incentive for national policymakers to adopt more stringent GHG emission mitigation efforts.

4 Concluding remarks

Impact assessments of ambitious climate mitigation strategies defined by the NDC targets have recently become an important agenda for policymakers. This study developed and applied a novel, transparent approach to assess possible links between climate and air pollution policies. An integrated framework was proposed to quantify potential synergies and trade-offs between the application of low-carbon and conventional power generation technologies. The framework is applicable globally and has been applied here to the Brazilian power supply sector as a case study.

There are significant synergies identified in our analysis between climate change mitigation and air pollution abatement for energy conversion technologies. In this case study of Brazil’s climate mitigation scenarios, synergies were found in the expansion of non-combustible renewables (wind and solar) and energy efficiency measures. These are two of the explicit pillars of the Brazilian NDC targets for the energy sector. However, for some of the impact categories considered, LAP indicators rose in response to GHG mitigation scenarios, indicating the existence of potential trade-offs. For instance, the rise of bioenergy in the climate mitigation scenarios may result in higher LAP indicators. Some of these negative outcomes can be offset by the introduction of pollution control methods commercially available today, such as filters and precipitators. Such a set of measures involves additional costs and energy penalties, which are, however, lower than the expenditures required for the transformation of the energy system and—if properly designed and operated—will not compromise its implementation.

The outcomes of this study are intended to bring the relevance to policymakers of local air pollution beyond national level analyses. However, results are, of course, subject to assumptions and uncertainties of modelling parameters, including emission factors, LAP control technologies, policy setups, technological characterisation of energy systems and overnight costs of generated electricity. Furthermore, this work does not include impacts on human health of the assessed impact categories (e.g. premature deaths due to ambient PM pollution), which would consider population density and air pollution dispersion models. These issues are relevant for deeper analyses in future studies.

Notes

For a review of barriers to energy efficiency implementation, see Limaye et al. (2008).

It is important to note that there are hidden costs and other market barriers, which hamper the implementation of energy efficiency measures, and that are not perceived in a purely least-cost optimization framework. Therefore, the LC0 scenario assumes that some policies to overcome these barriers are implemented.

To maintain consistency in the LAP assessment, the GHG emission factors reported here result from a separate analysis (see Section 2) and are slightly different than the ones used in the COPPE-MSB model, since they are more detailed in the composition of emissions from power plants.

Global Warming Potential.

References

Amann M, Bertok I, Borken-Kleefeld J, Cofala J, Heyes C, Höglund-Isaksson L, Klimont Z, Nguyen B, Posch M, Rafaj P, Sandler R, Schöpp W, Wagner F, Winiwarter W (2011) Cost-effective control of air quality and greenhouse gases in Europe: modeling and policy applications. Environ Model Softw 26:1489–1501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsoft.2011.07.012

Bollen J (2015) The value of air pollution co-benefits of climate policies: analysis with a global sector-trade CGE model called WorldScan. Technol Forecast Soc Chang 90:178–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2014.10.008

Castelo Branco DA, Moura MCP, Szklo A, Schaeffer R (2013) Emissions reduction potential from CO2 capture: a life-cycle assessment of a Brazilian coal-fired power plant. Energy Policy 61:1221–1235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2013.06.043

EEA (2013) EEA Technical report. EMEP/EEA air pollutant emission inventory guidebook. Technical guidance to prepare national emission inventories. Copenhagen, Denmark

EPE (2007) National energy plan 2030 (Plano Nacional de Energia 2030) (in Portuguese). EnergyResearch Agency, Rio de Janeiro

EPE (2015) 10-Year National Energy Plan (Plano Decenal de Energia 2024). Empresa de Pesquisa Energética

GoB (2015) Federative Republic of Brazil. Intended Nationally Determined Contribution (INDC) towards achieving the objective of the UNFCCC. Available at: http://www4.unfccc.int/submissions/INDC/Published%20Documents/Brazil/1/BRAZIL%20iNDC%20english%20FINAL.pdf. Accessed 16 Apr 2018

Goedkoop M, Heijungs R, Huijbregts M, De Schryver A, Struijs J, van Zelm R (2009) ReCiPe 2008 A life cycle impact assessment method which comprises harmonised category indicators at the midpoint and the endpoint level First edition. Report I: Characterisation. Netherlands

Hertwich E (2013) Addressing biogenic greenhouse gas emissions from hydropower in LCA. Environ Sci Technol 47:9604–9611. https://doi.org/10.1021/es401820p

IEA (2012) Hydropower and the environment: managing the carbon balance in freshwater reservoirs, guideline from quantitative analysis of net GHG emissions from reservoirs. International Energy Agency, Paris

IIASA (2016) GAINS global online - greenhouse gas - air pollution interactions and synergies. Available at: http://www.iiasa.ac.at/web/home/research/researchPrograms/air/GAINS.html. Accessed 16 Apr 2018

IPCC (2006) IPCC guidelines for national greenhouse gas inventories. In: HS Eggleston, L Buendia, K Miwa, T Ngara, K Tanabe (eds) Prepared by the National Greenhouse Gas Inventories Programme. IGES, Japan

Klausbruckner C, Annegarn H, Henneman LRF, Rafaj P (2016) A policy review of synergies and trade-offs in South African climate change mitigation and air pollution control strategies. Environ Sci Pol 57:70–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2015.12.001

Koberle A, Rochedo P, Portugal-Pereira J, Szklo AS, de Lucena AFP, Schaeffer R (2015) Brazil chapter. In: Spencer T, Pierfedericci R (eds) Beyond the numbers: understanding the transformation induced by INDCs. A report of the MILES project consortium. IDDRI - MILES project consortium, Paris, p 80

Lima F, Portugal-Pereira J, Lucena AFP, Rochedo P, Cunha J, Lopes Nunes M, Szklo AS (2015) Analysis of energy security and sustainability in future low carbon scenarios for Brazil. Nat Resour Forum 39:175–190. https://doi.org/10.1111/1477-8947.12081

Limaye DR, Heffner GC, Sarkar A (2008) An analytical compendium of institutional frameworks for energy efficiency implementation. Energy Sector Management Assistance Program (ESMAP), Washington DC

Lucena AFP, Clarke L, Schaeffer R, Szklo A, Rochedo PRR, Daenzer K, Gurgel A, Kitous A, Kober T (2015) Climate policy scenarios in Brazil: A Multi-Model Comparison for Energy. Energy Econ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2015.02.005

MCTI (2016) Third National Communication of Brazil to the United Nations framework convention on climate change. Government of Brazil. Brasília, Brazil. Available at: https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/natc/branc3v3.pdf. Accessed 16 Apr 2018

Myhre G, Shindell D, Bréon F-M et al (2013) Anthropogenic and natural radiative forcing. In: Stocker TF, Qin D, Plattner G-K, Tignor M, Allen SK, Boschung J, Nauels A, Xia Y, Bex V, Midgley PM (eds) Climate change 2013: The physical science basis. Contribution of working group I to the fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Portugal Pereira J, Troncoso Parady G, Castro Dominguez B (2014) Japan’s energy conundrum: post-Fukushima scenarios from a life cycle perspective. Energy Policy 67:104–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2013.06.131

Portugal-Pereira J, Esteban M (2014) Implications of paradigm shift in Japan’s electricity security of supply: a multi-dimensional indicator assessment. Appl Energy 123:424–434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2014.01.024

Portugal-Pereira J, Köberle AC, Soria R, Lucena AFP, Szklo A, Schaeffer R (2016) Overlooked impacts of electricity expansion optimisation modelling: the life cycle side of the story. Energy 115(Part 2):1424–1435. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2016.03.062; http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0360544216303061

Puppim de Oliveira JA, Doll CNH (2016) Governance and networks for health co-benefits of climate change mitigation: lessons from two Indian cities. Environ Int 97:146–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2016.08.020

Rafaj P, Schöpp W, Russ P, Heyes C, Amann M (2013) Co-benefits of post-2012 global climate mitigation policies. Mitig Adapt Strateg Glob Chang 18:801–824. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-012-9390-6

Rafaj P, Amann M, Siri J, Wuester H (2014) Changes in European greenhouse gas and air pollutant emissions 1960–2010: decomposition of determining factors. Clim Chang 124:477–504. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-013-0826-0

Rao S, Klimont Z, Smith SJ, Van Dingenen R, Dentener F, Bouwman L, Riahi K, Amann M, Bodirsky BL, van Vuuren DP, Aleluia Reis L, Calvin K, Drouet L, Fricko O, Fujimori S, Gernaat D, Havlik P, Harmsen M, Hasegawa T, Heyes C, Hilaire J, Luderer G, Masui T, Stehfest E, Strefler J, van der Sluis S, Tavoni M (2017) Future air pollution in the Shared Socio-economic Pathways. Glob Environ Chang 42:346–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2016.05.012

Rogelj J, den Elzen M, Hohne N, Fransen T, Fekete H, Winkler H, Schaeffer R, Sha F, Riahi K, Meinshausen M (2016) Paris Agreement climate proposals need boost to keep warming well below 2°C. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature18307

Schaeffer R, Szklo A (2001) Future electric power technology choices of Brazil. Energy Policy 29:355–369. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0301-4215(00)00130-0

Szklo A, Lucena A, Schaeffer R, Silveira Soares Filho B, Leroy Davis J, Rajão R, Amaral Haddad E,Domingues EP, Campos A, Koberle A, Ribeiro A, Lima E, Barbosa FA, Império M, Rochedo P, Maia S, Leles Souza Costa W (2017) Integrated modelling and economic impacts of sectoral low carbon options (Modelagem integrada e impactos econômicos de opções setoriais de baixo carbono) (in Portuguese). Brasília: Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia, Inovações e Comunicações, ONU Meio Ambiente, Brazil. Available at: https://www.csr.ufmg.br/csr/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Modelagem-Integrada.pdf. Accessed 16 Apr 2018

Thambiran T, Diab RD (2011) The case for integrated air quality and climate change policies. Environ Sci Pol 14:1008–1017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2011.08.002

UN (2015) Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015: Transforming our world:the 2030 agenda for sustainable development (a/res/70/1). New York City. Available at: http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_RES_70_1_E.pdf. Accessed 16 Apr 2018

van Harmelen T, Bakker J, de Vries B, van Vuuren D, den Elzen M, Mayerhofer P (2002) Long-term reductions in costs of controlling regional air pollution in Europe due to climate policy. Environ Sci Pol 5:349–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1462-9011(02)00043-6; http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1462901102000436

West JJ, Smith SJ, Silva RA, Naik V, Zhang YQ, Fry MM, Anenberg S, Horowitz LW, Lamarque J-FF, Adelman Z, Fry MM, Anenberg S, Horowitz LW, Lamarque J-FF (2013) Co-benefits of mitigating global greenhouse gas emissions for future air quality and human health. Nat Clim Chang Chang 3:885–889. https://doi.org/10.1038/NCLIMATE2009

Funding

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 642147 and the MILES project (Modelling and Informing Low Emission Strategies), financed by Directorate General Climate Action (DG CLIMA), under contract to DG CLIMA (No. 21.0104/2014/684427/SER/ CLIMA.A.4). The work is largely based on published scenarios from a series of energy-economy integrated assessment models. The results presented here are not automatically endorsed by MILES project partners. The authors also acknowledge the financial support of the Brazilian Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Highlights

• Interaction of climate policies and local air pollution for the power sector in Brazil

• Rising share of low-carbon technologies reduce terrestrial acidification impacts

• Potential trade-offs for CCS and bioenergy technologies regarding particulates and HT impacts

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 58 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Portugal-Pereira, J., Koberle, A., Lucena, A.F.P. et al. Interactions between global climate change strategies and local air pollution: lessons learnt from the expansion of the power sector in Brazil. Climatic Change 148, 293–309 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-018-2193-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-018-2193-3