Abstract

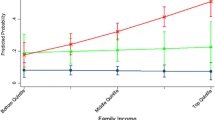

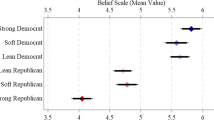

Research suggests that public divides on climate change may often be rooted in identity processes, driven in part by a motivation to associate with others with similar political and ideological views. In a large split-ballot national survey experiment of 2041 U.S. adults, we explored the role of a non-partisan identity—racial/ethnic majority and minority status—in climate change opinion, in addition to respondents’ political orientation (i.e., ideology and party affiliation). Specifically, we examined respondents’ climate beliefs and policy support, identification with groups that support environmental causes (“environmentalists”), and the sensitivity of these beliefs to other factors known to predict issue polarization (political orientation and issue framing). Results revealed that across all opinion metrics, non-Whites’ views were less politically polarized than those of Whites and were unaffected by exposure to different ways of framing the issue (as “global warming” versus “climate change”). Moreover, non-Whites were reliably less likely to self-identify as environmentalists compared to Whites, despite expressing existence beliefs and support for regulating greenhouse gases at levels comparable to Whites. These findings suggest that racial and ethnic identities can shape core climate change beliefs in previously overlooked ways. We consider implications for public outreach and climate science advocacy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

All interactive effects of race/ethnicity and political ideology on climate beliefs remain significant when controlling for party affiliation (Republican, Democrat) and other background variables known to predict environmental beliefs (i.e., gender, education, and income). Moreover, they emerge despite comparable variability in political ideology within both groups (SD = 1.47 vs. SD = 1.55, respectively; Range: 1–7 for both groups) (see Table 1 and Table 2).

We note that other researchers have similarly focused on effects of political ideology in the context of race (e.g., McCright and Dunlap 2011a and McCright and Dunlap 2011b). However, these studies did not examine interaction effects between race and political orientation among non-Whites (a direct test of differential political polarization), and importantly, they did not examine support for climate policies, indirect effects (e.g., via scientific consensus), or experimental effects of different issue frames – the focus of the present study.

References

Akerlof K, Maibach EW (2011) A rose by any other name…?: What members of the general public prefer to call “climate change.” Clim Chang 1–12

Baumer EP, Polletta F, Pierski N, Gay GK (2016). A simple intervention to reduce framing effects in perceptions of global climate change. Environ Communication

Bliuc AM, McGarty C, Thomas EF, Lala G, Berndsen M, Misajon R (2015) Public division about climate change rooted in conflicting socio-political identities. Nat Clim Chang 5:226–229

Bolsen T, Druckman JN (2016) Counteracting the politicization of science. J Commun

Chong D, Rogers R (2005) Racial solidarity and political participation. Polit Behav 27:347–374

Dietz T, Dan A, Shwom R (2007) Support for climate change policy: social psychological and social structural influences. Rural Sociol 72:185–214

Ding D, Maibach EW, Zhao X, Roser-Renouf C, Leiserowitz A (2011) Support for climate policy and societal action are linked to perceptions about scientific agreement. Nat Clim Chang 1:462–466

Dovidio JF, Gaertner SL, Pearson AR, Riek BM (2005) Social identities and social context: social attitudes and personal well-being. Ad Group Process 22:231–260

Finucane ML, Slovic P, Mertz CK, Flynn J, Satterfield TA (2000) Gender, race, and perceived risk: the ‘white male’ effect. Health Risk Soc 2:159–172

Flynn J, Slovic P, Mertz CK (1994) Gender, race, and perception of environmental health risks. Risk Anal 14:1101–1108

Goffman E (1959) The presentation of self in everyday life. University of Edinburgh

Green 2.0 (Formerly the Green Diversity Initiative). Leadership at Work. Retrieved from http://www.diversegreen.org/leadership/. Accessed 1 Jan 2016

Guber DL (2013) A cooling climate for change? Party polarization and the politics of global warming. Am Behav Sci 57:93–115

Hamilton LC (2011) Education, politics and opinions about climate change evidence for interaction effects. Clim Chang 104:231–242

Kahan DM, Braman D, Gastil J, Slovic P, Mertz CK (2007) Culture and identity-protective cognition: explaining the white-male effect in risk perception. J Empir Leg Stud 4:465–505

Kinder DR, Sanders, LM (1996) Divided by color: racial politics and democratic ideals. University of Chicago Press

Kinder DR, Winter N (2001) Exploring the racial divide: blacks, whites, and opinion on national policy. Am J Polit Sci 45:439–456

Krosnick JA, Holbrook AL, Visser PS (2000) The impact of the fall 1997 debate about global warming on American public opinion. Public Underst Sci 9:239–260

Leiserowitz A, Akerlof K (2010) Race, ethnicity and public responses to climate change. Yale Project on climate change communication, New Haven

Leiserowitz A, Feinberg G, Rosenthal S, Smith N, Anderson A, Roser-Renouf C, Maibach E (2014) What's in a name? Global warming vs. climate change. Yale University and George Mason University. Yale Project on Climate Change Communication, New Haven

Lorenzoni I, Leiserowitz A, de Franca DM, Poortinga W, Pidgeon NF (2006) Cross-National comparisons of image associations with “global warming” and “climate change” among laypeople in the United States Of America and Great Britain. J Risk Res 9:265–281

Malka A, Krosnick JA, Langer G (2009) The association of knowledge with concern about global warming: trusted information sources shape public thinking. Risk Anal 29:633–647

McCright AM (2008). The social bases of climate change knowledge, concern, and policy support in the U.S. general public. Hofstra L Rev 37:1017–1047

McCright AM, Dunlap RE (2011a) Cool dudes: the denial of climate change among conservative white males in the United States. Glob Environ Chang 21:1163–1172

McCright AM, Dunlap RE (2011b) The politicization of climate change and polarization in the American public's views of global warming, 2001–2010. Sociol Q 52:155–194

Mohai P (2008) Equity and the environmental justice debate. Res Soc Probl Publ Pol 15:21–49

Oreskes N, Conway EM (2011) Merchants of doubt: how a handful of scientists obscured the truth on issues from tobacco smoke to global warming. Bloomsbury Publishing USA

Palmer C (2003) Risk perception: another look at the 'white male' effect. Health Risk Soc 5:71–83

Pearson AR, Schuldt JP (2014) Facing the diversity crisis in climate science. Nat Clim Chang 4:1039–1042

Pearson AR, Schuldt JP (2015). Bridging climate communication divides: beyond the partisan gap. Sci Commun 37:805–812

Pearson AR, Schuldt JP, Romero-Canyas R. (2016). Social climate science: A new vista for psychological science. Perspect Psychol Sci (in press)

Pew (2014) U.S. Latino Social and Political Views http://www.pewforum.org/2014/05/07/chapter-9-social-and-political-views/

Schuldt JP, Konrath SH, Schwarz N (2011) “Global warming” or “climate change”? Whether the planet is warming depends on question wording. Public Opin Quart 75:115–124

Shaman J, Solomon S, Colwell RR, Field CB (2013) Fostering advances in interdisciplinary climate science. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:3653–3656

Speiser M, Krygsman K (2014) American climate values 2014: insights by racial and ethnic groups. Strategic Business Insights and ecoAmerica, Washington, DC

Suhay E, Druckman JN (2015) The politics of science: political values and the production, communication, and reception of scientific knowledge. Ann Am Acad Polit Soc Sci 658:6–15

Tajfel H, Turner JC (1979) An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In: Austin WG, Worchel S (eds) The social psychology of intergroup relations. Brooks/Cole, Monterey, pp. 33–47

Taylor DE (2007) Employment preferences and salary expectations of students in science and engineering. Bioscience 57:175–185

Taylor DE (2014) The State of Diversity in Environmental Organizations: Mainstream NGOs, Foundations and Government Agencies. Green 2.0 Working Group

UN Development Programme (2009) Global Human Development Report. http://hdrundp.org/sites/default/files/hdr_2009_en_summary.pdf

US Census Bureau (2010) Minority Census Participation. http://www.census.gov/2010census/mediacenter/awareness/minority-census.php

van der Linden S, Leiserowitz AA, Feinberg GD, Maibach EW (2015) The scientific consensus on climate change as a gateway belief: experimental evidence. PLoS One 10:e0118489

Villar A, Krosnick JA (2011) Global warming vs. climate change, taxes vs. prices: does word choice matter? Clim Chang 105:1–12

Washington Post-ABC News (2009) http://www.washingtonpost.com/wpsrv/politics/polls/postpoll_121509.html

Whitmarsh L (2008) What's in a name? commonalities and differences in public understanding of “climate change” and “global warming”. Public Underst Sci 18:401–420

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Time-sharing Experiments for the Social Sciences (TESS) (Jeremy Freese and James Druckman, Principal Investigators) for supporting this data collection. TESS is supported by the National Science Foundation (Grant SES-1227179).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schuldt, J.P., Pearson, A.R. The role of race and ethnicity in climate change polarization: evidence from a U.S. national survey experiment. Climatic Change 136, 495–505 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-016-1631-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-016-1631-3