Abstract

Parents are a vulnerable group to increased distress resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. In this study, 80 parents with at least mildly elevated internalizing symptoms were randomized to receive a four session, transdiagnostic intervention via telehealth during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic based on the Unified Protocols for Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders (UP-Caregiver), immediately or 6-weeks after receipt of psychoeducational materials. Results showed no between-condition differences in slopes of primary outcome measures; however, significant group differences in intercepts indicated that those receiving UP-Caregiver immediately had greater improvements in distress tolerance and intolerance of uncertainty than those in the delayed condition. Analyses also suggested within-condition improvements in emotional functioning and high satisfaction with UP-Caregiver. Results suggest that psychoeducation and symptom monitoring may be helpful to some distressed parents. Future investigations should utilize a larger sample to identify which parents might benefit the most from interventions like UP-Caregiver during crises.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has posed unprecedented health, economic, political, and psychological challenges in the United States [1, 2]. Anxiety, uncertainty, social distancing, and decreased social support related to the outbreak led to increased psychological distress and worsening of existing mental health concerns among many individuals in the United States [3,4,5,6]. For parents and caregivers of children, in particular, the pandemic posed unique challenges that may directly impact both parents’ and youths’ mental health [7, 8]. Like other adults, parents were burdened with sudden disruptions in daily routines, financial hardships, scarcity of resources, perceived health risks, and discrimination related to the virus and lifestyle changes. Yet, additional stressors including balancing work, recurrent school closures, and sustaining basic childcare needs distinctly impacted parents’ well-being relative to adults without youth at home [7, 9], particularly early in the pandemic. Indeed, parenting demands became increasingly complex and variable during the pandemic [10] and such parenting stressors placed some parents at risk for experiencing elevated levels of anxiety, depression, and traumatic stress [7, 11]. As well, parents with pre-existing anxiety and depression prior to the pandemic appeared to be at heightened risk for worsening of symptoms as result of COVID-19-related stressors [4, 5].

Persons with emotional disorder symptoms, such as anxiety, depression, and traumatic stress experience frequent, strong emotions and difficulty managing related emotional responses (i.e., thoughts, feelings, and behaviors). Persons with these symptoms may engage in unhelpful, but understandable behaviors (e.g., suppression, avoidance, substance use, angry outbursts) in an attempt to initially decrease the intensity of their emotions. Although unhelpful in the long term, these behaviors typically provide short-term distress relief, thereby negatively reinforcing maladaptive coping [12]. Difficulties with emotion regulation conferred by low distress tolerance, high anxiety sensitivity, and greater intolerance of uncertainty, which may collectively be described as affect intolerance [13], further increase an individuals’ risk for developing and/or maintaining emotional disorder symptoms [14, 15], which appeared particularly true during the pandemic [16, 17]. Consistent use of adaptive emotion regulation strategies may be important for parents’ ability to be flexible, responsive, and perceptive [18, 19], especially when managing stressors, addressing challenging child behaviors, problem-solving, and making decisions [18, 20]. For example, during COVID-19, Shorer and Leibovich [21] found that parental emotion regulation fully mediated the relationship between exposure to stress and children’s stress reactions. Parents who struggle with greater levels of psychopathology are also more likely to be emotionally reactive to stressors [22] and are less likely to cope adaptively to difficult circumstances [e.g., unemployment, household chaos; 23, 24]. Risk factors associated with affect intolerance may then be particularly important treatment targets for parents experiencing elevated emotional disorder symptoms during the pandemic.

Parents affected by psychopathology and emotion regulation deficits may engage in unhelpful emotional parenting behaviors [e.g., critical, overcontrolling, low empathy or warmth; 24, 25], partially as a means of reducing their own or their child’s distress or due to elevated intolerance of uncertainty in moments of stress [26]. Parents can be overprotective and/or irritable following a traumatic event [27, 28]. Disaster events, including the COVID-19 pandemic, are also associated with increased hostile parenting behaviors [29]. During the pandemic, parents’ caregiving burden, depressive symptoms, and perceived child stress have been significantly associated with greater parent–child conflict and lower closeness [11].

Psychopathology and engagement in maladaptive parenting strategies can also impact parents’ beliefs about their own parenting capacities. Parental self-efficacy (PSE), or the expectation parents hold about their ability to provide care to their children successfully, is strongly associated with parents’ stress, anxiety, depression, and PTSD symptoms [30], and lower PSE may predict greater child internalizing and externalizing symptoms [31]. Although few studies have evaluated the role of PSE during COVID-19, some parents with lower PSE reported having a lower quality of life during the pandemic [32]. Further, higher pandemic stress and greater child psychosocial problems were associated with caregivers’ reduced PSE and worsened caregiver mental health symptoms [33]. Parenting difficulties and increased stress due to the pandemic may leave parents feeling even less efficacious and result in the use of less adaptive parenting behaviors that inadvertently maintain challenging child behaviors [34], particularly in light of poorer parent emotion regulation.

A transdiagnostic intervention approach directed at parent psychopathology, emotion regulation and coping may be particularly well-suited to address the needs of vulnerable parents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, the Unified Protocols for Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders in Adults [UP; 12] and Children and Adolescents [UP-C and UP-A; 35] have demonstrated efficacy in reducing emotional disorder symptoms and improving daily functioning across numerous investigations [36,37,38,39,40]. Through use of evidence-based cognitive behavior therapy and mindfulness techniques, the UP protocols focus on addressing aspects of affect intolerance implicated in the development and maintenance of emotional disorders. The UP-C/A, predominately child-directed treatments, offer a targeted approach to youth symptoms and also address parenting characteristics and behaviors shown to confer vulnerability to youth emotional disorders [e.g., accommodation of child anxiety-related behaviors; 35, 41]. This approach uses concepts from emotion socialization theory [42] to address unhelpful parenting behaviors of inconsistent reinforcement and discipline, criticism, intrusive parenting, and unhelpful modeling of emotions and avoidance. Notably, an open trial examining the effects of the UP-C/A on parent emotion regulation suggested these protocols were effective in decreasing unsupportive parenting behaviors and in addressing parents’ emotion difficulties [43]. The UP-C/A were recently adapted to develop the Coping with COVID program, a six-session parent-directed intervention to help youth with emotional disorders cope with the pandemic [44]. Although this intervention focused on teaching parents how to implement CBT strategies with their children, results showed large effects on COVID-19 specific concerns at post-treatment, suggesting that the adapted protocol was effective in addressing pandemic-related concerns. Taken together, the UP protocols show promise as an adaptable intervention model for addressing the needs of parents with elevated emotional disorders symptoms during the current pandemic.

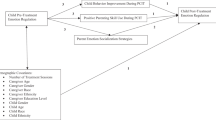

Given the paucity of parent-directed interventions for parents’ emotions and related behaviors during a crisis like COVID-19, UP-Caregiver [45] was further modified as a brief, preventative intervention for parents with elevated emotional disorder symptoms in the context of the pandemic. UP-Caregiver is comprised of select strategies from the adult UP and parent-directed strategies from the UP-C to improve parent emotion regulation, coping focusing on current COVID-19-related stressors most relevant to parents, and effective parenting behaviors (i.e., strategic attention, healthy emotion modeling, empathy). Strategies were presented in the context of the pandemic via modified examples of relevant stressors and techniques. The current study evaluated the initial effects of UP-Caregiver in a sample of parents with elevated emotional disorder symptoms. Primary outcomes included changes in self-reported emotional disorder symptoms (i.e., anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress). Secondary outcomes included changes in underlying mechanisms of emotional disorder symptoms, and self-reported parent belief and behaviors (i.e., PSE, parenting satisfaction, accommodation). Feasibility and acceptability were also evaluated. We hypothesized that caregivers would improve; however, we were unsure if improvements would be substantially greater than the provision of psychoeducational materials and study monitoring.

Methods

Participants

Participants were parents with at least one child aged 6–13 years old in their household and who lived in the state where the study was conducted during their study participation. All participants were biological parents or foster parents of at least one child in the age range and are therefore collectively referred to as “parents” hereafter. Participants were excluded if they were previously diagnosed with or treated for bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, psychosis, or substance use disorder or had been hospitalized for mental health concerns or a suicide attempt. Inclusion criteria included an elevated score on a self-report questionnaire of anxiety, depression, and/or post-traumatic stress symptoms indicated by the Generalized Anxiety Disorder seven-item scale [GAD-7; 46], Patient Health Questionnaire [47], and Primary Care PTSD Screen for DSM-5 [48], respectively. A total of 100 participants were eligible and 80 participants were ultimately randomized to a study condition, with 52 participants in the immediate treatment condition and 28 participants in the delayed treatment condition (randomized 2:1 [immediate: delayed condition], blocked by stated preference for Spanish- vs. English-language UP-Caregiver groups). See Fig. 1 for CONSORT diagram.

The final sample ranged from 25 to 52 years old (M = 40.14, SD = 6.41) and was 95% cisgender female. Approximately 54% of the sample identified as white and Latinx, 37% identified as white non-Latinx, 3% identified as Multiracial, 3% identified as Multiracial and Latinx, one participant identified as Black or African American and Latinx (1.25%), one participant identified as Asian (1.25%), and one participant (1.25%) identified as Latinx, race unspecified. Most parents (91.3%) participated in English language groups and 8.7% of the parents participated in Spanish language groups. See Table 1 for a summary of sample characteristics and pre-randomization group comparisons.

Measures

In addition to the self-report measures below, parents answered general demographic questions and questions about the children in their home. Parents also reported on their family’s COVID-19 related experiences using the Coronavirus/COVID Experiences Questionnaire [49]. All measures were administered at Weeks 0, 2, 4, 6, and 12, unless otherwise noted.

Symptom Measures

The Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale [OASIS; 50] is a five-item measure that assesses severity and impairment of anxiety symptoms. A cut-off score of an eight can be used to classify individuals in a clinical sample as having an anxiety disorder or not [51]. The OASIS has demonstrated excellent reliability and validity in clinical and nonclinical samples [50, 51]. Internal consistency in the current sample was good across timepoints (α = 0.78–0.88).

The Overall Depression Severity and Impairment Scale [ODSIS; 52] is a five-item measure that assesses the severity and impairment of mood disorder symptoms. A cut-off score of an eight can correctly classify most individuals as having a mood disorder. The ODSIS has demonstrated excellent internal consistency and good convergent and discriminant validity in clinical and nonclinical samples [52]. Internal consistency in the current sample was excellent (α = 0.92–0.97).

The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 [PCL-5; 48] is a 20-item measure designed to screen for and monitor PTSD symptoms. The PCL-5 can be scored in several ways to derive a provisional PTSD diagnosis, and a cut-off score between 31 and 33 indicates probable PTSD. The PCL-5 has shown excellent reliability and validity in trauma-exposed samples [48]. Internal consistency in the current sample was excellent (α = 0.92–0.96).

Affect Intolerance Measures

The Distress Tolerance Scale [DTS; 53] is a 15-item measure of perceived ability to tolerate negative emotions. The DTS has demonstrated excellent psychometric properties in general and clinical populations [54, 55]. In the current sample, the internal consistencies for the total score and subscales ranged from good to excellent (α = 0.74–0.93).

The Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale [IUS-12; 56] is a 12-item scale measuring perceived ability to tolerate uncertain situations. The IUS-12 has demonstrated good psychometric properties in nonclinical and clinical anxiety samples [56, 57]. In this sample, internal consistency ranged from good to excellent (α = 0.79–0.95).

The Anxiety Sensitivity Index [ASI; 58] is a 16-item measure that assesses how responsive an individual is to symptoms of anxiety and consists of a total score and three subscales: physical, mental, and social. The ASI has shown good psychometric properties in clinical and nonclinical samples [59]. In the current sample, the internal consistencies for the total score and the physical and mental subscales ranged from strong to excellent (α = 0.83–0.96); however, the social subscale varied from questionable to acceptable (α = 0.59–0.70).

Parenting Measures

The Parenting Sense of Competence Scale [PSOC; 60] is a 17-item measure of total PSE, parenting satisfaction, and parenting efficacy. The PSOC has demonstrated good psychometric properties in nonclinical and treatment-seeking samples [61,62,63,64,65]. The internal consistencies for the total score and subscales ranged from acceptable to excellent (α = 0.72–0.92).

The Family Accommodation Scale—Anxiety [FASA; 66] is a 13-item measure assessing parents’ accommodation of their children’s anxiety symptoms and behaviors and distress related to accommodation. The FASA has demonstrated strong psychometric properties for treatment-seeking parents [66]. The FASA was administered at Weeks 0, 6, and 12 and demonstrated excellent internal consistency (α = 0.91–0.94).

Feasibility and Acceptability Measures

The Therapy Attitude Inventory [TAI; 67] is a 10-item measure that was administered at Weeks 6 and 12 to assess treatment satisfaction in regard to parenting and the parent–child relationship. The TAI showed excellent internal consistency (α = 0.94).

Additionally, following each session, caregivers were emailed and asked to rate how satisfied they were with the session, from 1 not satisfied to 5 extremely satisfied, and how helpful they found the session, from 1 not at all helpful to 5 extremely helpful. Caregivers were also invited to share any qualitative comments or feedback about the session.

Procedures

The study was approved by the University’s Institutional Review Board and registered with ClinicalTrials.gov. It was conducted from May 2020 to November 2020. Participants were recruited via social media, organization talks, listservs, and institution websites and consented electronically. Initially eligible participants who completed Week 0 questionnaires were contacted to complete a brief phone screen for further screening. Parents who endorsed a history of child abuse or endangerment were referred out. Parents who endorsed suicidal ideation on the PHQ-9 were evaluated with the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale [68] and were referred out if they were more than moderate risk. Randomized participants were administered surveys as indicated above. They were compensated up to $175 for their participation.

The immediate treatment condition received UP-Caregiver following randomization. The delayed treatment condition received psychoeducation about coronavirus-related stressors and coping with stress developed by the National Child Traumatic Stress Network [NCTSN; 69] in their preferred language at the time of randomization, and additional self-reports at Weeks 2, 4 and 6. After completing the Week 6 assessment, they were offered the UP-Caregiver group.

The UP-Caregiver intervention is comprised of four 90-min sessions [45]. It was administered using a rolling group format (e.g., following Session 1, sessions were received in any order, depending on when participants entered groups) with up to six caregivers and two therapists per group. Parents continued to attend until they received all four sessions and could opt to repeat content and participate in up to eight sessions. Therapists (n = 10) were doctoral students, a post-doctoral fellow, and faculty members who had previously completed UP-C/A training. Treatment fidelity was live coded by trained research assistants. Across all sessions of the four modules, treatment components were adhered to 67.6–100% of the time. Table 2 outlines the content of each UP-Caregiver session. More information about UP-Caregiver and its development can be found in Ehrenreich-May et al. [45].

Preliminary Analyses

Following the completion of data collection, data were entered and checked for errors and outliers. Estimates of skewness and kurtosis were examined and found to be within normal limits. Analyses show that the data were missing completely at random (Little’s MCAR test: χ2 = 7107.47, df = 10,914, p = 1.0). Initial analyses included descriptive statistics calculated from the clinical and demographic items to summarize the sample characteristics. At Week 0, parents in the delayed treatment condition (M = 11.57, SD = 3.00) reported significant higher anxiety severity than parents in the immediate treatment condition (M = 9.94; SD = 3.5), t(78) = −2.07, p = 0.04. There were no other between-condition differences on any of the outcome or demographic variables.

Data screening of baseline anxiety severity scores and use of the interquartile range revealed two outliers in the immediate treatment condition that were not due to measurement error. Although the two individuals identified reported lower anxiety scores on the OASIS than others in the sample, their reports of anxiety on the GAD-7 and their reports of depressive and PTSD symptoms were not outliers. Further, both participants fell within the same classification of moderate anxiety, indicated by a total score greater than 10 on the GAD-7 (immediate treatment group: M = 12.1, SD = 4.75; M = 11.57, SD = 3.0; [70]). Thus, the participants were retained and anxiety severity was not controlled for in the analyses.

Piecewise multilevel modeling [MLM; see 71–73] was employed using HLM software [74] to account for nesting of (1) Repeated measures for each participant, (2) Each participant, and (3) Participants nested within their group therapists, with one ID number assigned for each unique pair of therapists (or single therapists in the case of groups run by just one clinician). A total of 67 unique therapist codes were identified for the participants. Although most participants remained in their same group, for cases in which participants switched to another group, participants were nested according to the therapist(s) they worked with the most.

Piecewise modeling allows for examination of time segments within repeated measures data [75]. Our piecewise approach specified a Level 1 model including a linear segment between Week 0 and Week 6 (S1) and another linear segment for Week 6 and Week 12 (S2). Time was centered at Week 6 so that the intercept reflected outcome means at Week 6 [76], which was the end of treatment for the immediate treatment condition and the end of the delay period for the delayed treatment condition. Differences between the two treatment conditions were tested by entering treatment as a predictor of the Level 2 growth curve parameters (the intercept and both slopes). All models included random effects of the intercept. Group difference effect sizes at the intercept were calculated by dividing the group difference intercept parameter by the raw score standard deviation. In accordance with Feingold [77], group difference effect sizes for change over time during S1 and S2 were calculated by multiplying the group difference slope coefficient by the length of S1 and S2 and dividing it by the raw data standard deviation. Effect size magnitude was evaluated using Cohen’s d classification of 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8 for small, medium, and large effects, respectively.

Results

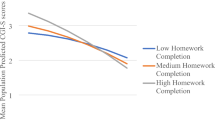

Group differences in outcome variables at the Week 6 timepoint were determined by evaluating significant differences in intercepts. Table 3 presents estimated coefficients, p-values, and effect sizes for group differences at Week 6. There were no significant differences in the groups’ reports on symptomatology (i.e., anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress), anxiety sensitivity, or parent self-efficacy at Week 6. The immediate treatment group did report significantly lower scores on overall intolerance of uncertainty (b = 29.56) and desire for predictability (IUS-12 Prospective, b = 18.80) than the delayed treatment condition (b = 34.61 and b = 22.04, respectively). The immediate treatment group also reported significantly higher total distress tolerance (b = 3.31), ability to tolerate emotions (DTS Tolerance, b = 3.33), and ability to regulate emotion (DTS Regulation, b = 3.21) than the delayed treatment group (b = 2.84, 2.70, and 2.50, respectively). Table 3 also presents group difference coefficients, p-values, and effect sizes for S1 and S2. There were no significant Time by Condition effects for the variables examined.

Due to a lack of between-condition findings in slopes, changes in slope for the initial reference group (immediate treatment condition) were interpreted to investigate within-condition changes in outcomes. The models were then rerun with the delayed treatment condition as the reference group to determine if there were any within-condition changes for this group.

Within-Condition Results for S1

During S1, parents in the immediate treatment condition reported significant improvements in anxiety (b = −0.46, p < 0.001), depressive (b = −0.33, p < 0.001), and post-traumatic stress symptoms (b = −0.78, p = 0.004). They also reported decreased intolerance of uncertainty (b = −0.58.19, p = 0.002), decreased desire for predictability (b = −0.33, p = 0.003), and decreased inhibition due to uncertainty (IUS-12 Inhibitory, b = −0.24, p = 0.007). They reported significant improvements in total distress tolerance (b = 0.04, p = 0.006) and in their assessment of emotional situations as acceptable (DTS Appraisal, b = 0.05, p = 0.002), and trending improvements in the extent to which their attention was absorbed by negative emotions (DTS Absorption, b = 0.04, p = 0.07) and their ability to regulate emotion (b = 0.03, p = 0.06); however, they reported no changes in ability to tolerate emotions (b = 0.03, p = 0.22). These parents also reported significant improvements in overall anxiety sensitivity (b = −0.53, p = 0.01) and physical anxiety sensitivity (b = −0.35, p = 0.006); however, they reported no changes in mental or social anxiety sensitivity. During these 6-weeks of active treatment, parents also reported significant increases in their overall parent self-efficacy (b = 0.44, p = 0.007) and parenting satisfaction (b = 0.25, p = 0.05), but not in the efficacy subscale (b = 0.18, p = 0.12). Finally, parents reported trending improvements in their participation in their children’s anxiety-driven behaviors (b = −0.17, p = 0.07) and significant improvements in distress related to accommodation (b = −0.19, p = 0.02), but no changes in their reports of modification of family routines and schedules due to anxiety (b = −0.10, p = 0.36).

During S1, parents in the delayed treatment condition reported significant improvements in anxiety (b = −0.48, p < 0.001), depressive (b = −0.40, p = 0.002), and post-traumatic stress symptoms (b = −1.14, p = 0.002), despite receiving no intervention during this window. They reported no changes in intolerance of uncertainty during this time and reported significant improvements in only the appraisal domain of distress tolerance (b = 0.05, p = 0.04). Similar to the immediate treatment condition, the delayed treatment condition reported significant improvements in overall anxiety sensitivity (b = −0.67, p = 0.02) and physical anxiety sensitivity (b = −0.49, p = 0.004), but not mental or social anxiety sensitivity. Lastly, parents reported significant improvements in overall parent self-efficacy (b = 0.67, p = 0.002), as well as improvements on the efficacy subscale (b = 0.30, p = 0.05). They did not report any changes in parenting satisfaction or any changes in accommodation of their children’s anxiety.

Within-Condition Results for S2

During their 6-week follow-up window (S2), parents in the immediate treatment condition reported significant increases in anxiety (b = 0.52, p < 0.001). However, they reported no additional changes in depressive (b = 0.19, p = 0.24) or post-traumatic stress symptoms (b = 0.50, p = 0.28), suggesting that the improvements experienced during S1 were maintained. Reports of overall intolerance of uncertainty (b = 0.68, p = 0.04) and inhibition related to uncertainty (b = 0.34, p = 0.03) increased since S1, yet desirability for predictability remained stable (b = 0.34, p = 0.07). Regarding distress tolerance, parents in the immediate treatment condition reported no additional changes in total distress tolerance, ability to regulate emotions, tolerate emotions, or attention to negative emotions; however, the extent to which they appraised emotions as acceptable worsened (b = −0.06, p = 0.03). Reports of total anxiety sensitivity and its specific domains did not significantly change from the treatment window to the follow-up window, nor did reports of parent self-efficacy or accommodation of their children’s anxiety.

During S2, the active treatment window for the delayed treatment group, parents in this condition reported subsequent increases in anxiety (b = 0.45, p = 0.02), depressive (b = 0.49, p = 0.03), and post-traumatic stress symptoms (b = 1.19, p = 0.06). Like their reports during the delay window, they reported no changes in intolerance of uncertainty and no additional changes in overall or specific domains of distress tolerance, anxiety sensitivity, parent self-efficacy or satisfaction, or accommodation of child anxiety during their active treatment window.

Feasibility and Acceptability

Across both conditions, caregivers participated in M = 3.25 (SD = 2.04, range = 0–8) sessions of UP-Caregiver, no differences between conditions (immediate treatment condition M = 3.27, SD = 1.95, range = 0–8; delayed treatment condition M = 3.21, SD = 2.23, range = 0–8; t(78) = 0.11, p = 0.91). Caregivers who completed the satisfaction and helpfulness questions reported an average satisfaction rating of 4.33 (SD = 0.66), which falls between the descriptors of “very satisfied” and “extremely satisfied.” There were no differences in how satisfied the groups were with the sessions (immediate treatment condition M = 4.26, SD = 0.69; delayed treatment condition M = 4.48, SD = 0.59; t(61) = −1.26, p = 0.21). Similarly, caregivers reported that the UP-Caregiver sessions were “very helpful” (M = 4.26, SD = 0.74) and helpfulness ratings did not differ between groups (immediate treatment condition M = 4.16, SD = 0.72; delayed treatment condition M = 4.44, SD = 0.76; t(61) = −1.46, p = 0.15). Parents noted that, “the session(s) gave me the ability to be ‘heard’,” that “sometimes I need to be reminded that I know what I'm doing as a parent,” and “the practice of the techniques has helped improve the quality of life in my home.” One parent reflected on their implementation of skills the same night after their session: “I already applied the empathy techniques at dinner and was able to connect with my child, prevent a meltdown and control my reactions when he refused to come to eat at the table with us … we were able to have a peaceful dinnertime that did not happen in a long time.”

On the TAI, the participants in the immediate treatment condition reported positive attitudes about the intervention at Week 6 (M = 38.58, SD = 6.05), which remained highly positive at Week 12 (M = 38.40, SD = 6.54). At Week 12, participants in the delayed treatment condition also reported positive attitudes about the intervention (M = 38.58, SD = 7.56), with no significant difference in attitudes towards the intervention between conditions, t(66) = −0.10, p = 0.92.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate the feasibility and clinical utility of a brief, transdiagnostic intervention for parents during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic (March – December 2020) compared to a delayed treatment condition that included enhanced participant monitoring and support materials. Across all outcome measures and timepoints, there were no significant between-condition differences in slopes. At Week 6, there were significant group differences such that, after receiving treatment, those receiving UP-Caregiver immediately reported lower overall intolerance of uncertainty and desire for predictability and higher distress tolerance, ability to tolerate emotions, and ability to regulate emotion compared to participants in the delayed treatment condition. Analyses showed that participants in the immediate treatment condition reported improved anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress symptoms during their active treatment window (S1); however, the participants in the delayed condition also reported significant improvements in these domains, despite S1 being their delay window. Further, participants in the delayed intervention condition reported worsened depressive and post-traumatic stress symptoms, and no changes in anxiety, during S2, which is when we expected to see improvements for the delayed treatment condition. Regarding changes in affect intolerance and parenting belief outcome measures, during the active treatment window for the immediate treatment condition, participants in both conditions reported significant improvements in PSE, anxiety sensitivity, and distress tolerance. However, participants who received the UP-Caregiver intervention during that time reported significant improvements in parenting satisfaction, intolerance of uncertainty, and distress related to accommodation, while the those in the delayed treatment condition did not. On the other hand, the delayed group reported significant improvements in PSE, while the immediate treatment condition did not. During S2, participants in the immediate treatment condition reported worsened intolerance of uncertainty and distress tolerance, while those in the delayed treatment condition reported no changes since Week 6. Despite these mixed findings, across all participants who received the UP-Caregiver intervention, parents reported high levels of satisfaction and reported the intervention to be helpful.

The effects of clinical attention and provision of support materials on the delayed group participants could have contributed to lack of Time by Condition findings in slopes. Participants in the delayed treatment condition completed study measures four times before initiating services, along with receipt of a useful resource in the NCTSN handout, and this increased clinical attention plus psychoeducation may have provided parents with a sufficient sense of support or self-awareness, as they awaited the upcoming treatment group. Research supports the notion that wait-list control conditions can produce greater effect sizes than no treatment conditions and that different control conditions can have unanticipated effects on participants’ expectations and behaviors [78]. Additionally, during a time when many were experiencing feelings of helplessness [79], participating in a research study, commonly recognized as a positive contribution to society [80], and reflecting on one’s own behaviors and emotions or having a support resource sheet handy, could have exerted a positive influence on participants. Moreover, similar null time x group results have been seen in another COVID-19-era intervention that aimed to reduced parental stress that included a waitlist control, underscoring the possibility that minimal clinical intervention may be sufficient to yield improvements for some parents during the pandemic [81]. Another possibility is that caregivers who self-select into this type of parenting prevention trial are particularly able and/or motivated to improve their current functioning, and thus, either the enhanced self-monitoring in the waitlist condition or the overt skill focus of the UP-Caregiver sessions may have been sufficient to modify symptoms.

It’s also possible that we recruited participants as they were returning to their natural baseline of parenting concerns, leaving less room for improvements, and leading to improvements despite not receiving treatment. Recent research evaluating the changes in parents’ mental health supports parents’ resilience over the course of the pandemic. Longitudinal studies show that adults in America and the United Kingdom reported significant increases in distress in the early weeks and months of the pandemic that then returned to baseline over the latter part of 2020 [82, 83]. Additionally, some parents may have experienced reduction in stressors during their participation in the study. Especially in the part of the United States where this study was conducted, which re-opened sooner than other regions, it’s possible that these parents had increased access to childcare supports and their own social supports due to re-openings, relaxed social distancing guidelines, and summer vacation that co-occurred with the study timeline. Identifying which parents benefit from a waitlist condition alone, a brief CBT intervention, or who need longer therapeutic care would help in triaging parents to scalable interventions appropriate for their needs [84]. This may be especially important given the shortage of mental health professionals to meet the increased needs of this population [85].

This study is not without limitations. First, the sample size was relatively small, and the comparison condition sample size was even smaller; future work should evaluate the effects of UP-Caregiver with a sufficiently powered sample. Further, the sample lacked characteristics important for generalizability to other populations, particularly regarding racial diversity of participants. This sample predominately identified as white and Latinx. Additionally, the parents in this sample were highly educated, with 33.8% of the sample having completed a graduate degree. Although Latinx populations were disproportionately impacted by the pandemic, it is well-known that white and highly educated individuals were least impacted by the detriments of the COVID-19 pandemic and thus results may lack generalizability to some other populations experiencing amplified negative effects of the crisis due to systemic inequities [86, 87]. Further, the parents who participated in this study were support-seeking parents with sufficient time and capacity to participate. We also excluded parents with serious mental illness or who were previously investigated for child abuse or neglect who may or may not have benefitted from UP-Caregiver. Second, the inclusion criteria included elevated symptoms of anxiety, depressive, or post-traumatic stress; however, a higher threshold for symptoms may have resulted in a greater effect on outcome variables.

Additionally, due to the time-sensitive nature of the target of the intervention, the developers did not conduct qualitative research during the treatment development process to understand who UP-Caregiver is best suited for and which skills and concepts felt most relevant for those individuals. However, the needs of parents are constantly shifting throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, some parents in this study experienced difficulties regulating anger, demonstrating empathy, using self-care, and engaging in flexible problem-solving, while others struggled with getting behaviorally activated, creating new routines and schedules, and having discussions with their children about the pandemic. Needs such as these have likely shifted since this time. Constructing a personalized version of UP-Caregiver in which parents could self-select intervention targets that are most applicable to them may optimize the quality of the intervention, increase efficiency, and offer parents an intervention experience that is fit to their needs at a given time.

UP-Caregiver continues to be an applicable intervention as the COVID-19 pandemic carries on. However, identifying potential mediators and moderators to indicate which parents have a greater need for immediate services, for whom a briefer or more prolonged intervention is needed, and which parents will exhibit a natural recovery could help streamline the intervention and assist in triaging parents to facilitate large-scale implementation efforts.

Summary

This study is one of few investigations to use a randomized design to observe parent psychopathology and affect intolerance following a brief, transdiagnostic intervention aimed to improve parent emotion regulation, manage pandemic-related stress, and increase adaptive parenting behaviors. Participants reported that UP-Caregiver was satisfying and helpful, and several anecdotal accounts highlight the impact that the intervention had for individual participants [88], if not a substantially greater one than the supports offered via the control condition.

References

Schuchat A, CDC Covid-19 Response Team (2020) Public health response to the initiation and spread of pandemic covid-19 in the united states. MMWR 69:551–556

Gruber J et al (2021) Mental health and clinical psychological science in the time of covid-19: challenges, opportunities, and a call to action. Am Psychol 76:409

Robinson E, Daly M (2021) Explaining the rise and fall of psychological distress during the covid-19 crisis in the United States: longitudinal evidence from the understanding America study. Br J Health Psychol 26:570–587

French MT, Mortensen K, Timming AR (2020) Psychological distress and coronavirus fears during the initial phase of the covid-19 pandemic in the united states. J Ment Health Policy Econ 23:93–100

Asmundson GJG, Paluszek MM, Landry CA, Rachor GS, McKay D, Taylor S (2020) Do pre-existing anxiety-related and mood disorders differentially impact covid-19 stress responses and coping? J Anxiety Disord 74:102271

Zheng J et al (2021) Psychological distress in north america during covid-19: the role of pandemic-related stressors. SSM 270:113687

Patrick SW et al (2020) Well-being of parents and children during the covid-19 pandemic: a national survey. Pediatrics 146:e2020016824

Kerr ML, Fanning KA, Huynh T, Botto I, Kim CN (2021) Parents’ self-reported psychological impacts of covid-19: associations with parental burnout, child behavior, and income. J Pediatr Psychol 46:1162–1171

Freisthler B, Gruenewald PJ, Tebben E, McCarthy KS, Wolf JP (2021) Understanding at-the-moment stress for parents during covid-19 stay-at-home restrictions. SSM 279:114025

Buheji M et al (2020) Children and coping during covid-19: a scoping review of bio-psycho-social factors. Int J Appl Psychol 10:8–15

Russell BS, Hutchison M, Tambling R, Tomkunas AJ, Horton AL (2020) Initial challenges of caregiving during covid-19: caregiver burden, mental health, and the parent–child relationship. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 51:671–682

Barlow DH et al (2017) Unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders: therapist guide. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Shaw AM, Llabre MM, Timpano KR (2015) Affect intolerance and hoarding symptoms: a structural equation modeling approach. Int J Cogn Ther 8:222–238

Keough ME, Riccardi CJ, Timpano KR, Mitchell MA, Schmidt NB (2010) Anxiety symptomatology: the association with distress tolerance and anxiety sensitivity. Behav Ther 41:567–574

McEvoy PM, Mahoney AEJ (2012) To be sure, to be sure: intolerance of uncertainty mediates symptoms of various anxiety disorders and depression. Behav Ther 43:533–545

Liu CH, Zhang E, Wong GTF, Hyun S, Hahm HC (2020) Factors associated with depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptomatology during the covid-19 pandemic: clinical implications for us young adult mental health. Psychiatry Res 290:113172

Saulnier KG, et al. (2021) Anxiety sensitivity and intolerance of uncertainty are unique and interactive risk factors for covid-19 safety behaviors and worries. Cogn Behav Ther 1–12

Kienhuis M, Rogers S, Giallo R, Matthews J, Treyvaud K (2010) A proposed model for the impact of parental fatigue on parenting adaptability and child development. J Reprod Infant Psychol 28:392–402

Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, Rudolph J, Kerin J, Bohadana-Brown G (2022) Parent emotional regulation: a meta-analytic review of its association with parenting and child adjustment. Int J Behav Dev 46:63–82

Barrett J, Fleming AS (2011) Annual research review: all mothers are not created equal: neural and psychobiological perspectives on mothering and the importance of individual differences. JCPP Adv 52:368–397

Shorer M, Leibovich L (2020) Young children’s emotional stress reactions during the covid-19 outbreak and their associations with parental emotion regulation and parental playfulness. Early Child Dev Care 1–11

Skowron EA, Friedlander ML (1998) The differentiation of self inventory: development and initial validation. J Couns Psychol 45:235

Deater-Deckard K (2014) Family matters: intergenerational and interpersonal processes of executive function and attentive behavior. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 23:230–236

Crandall A, Deater-Deckard K, Riley AW (2015) Maternal emotion and cognitive control capacities and parenting: a conceptual framework. Dev Rev 36:105–126

Zalewski M, Lewis JK, Martin CG (2018) Identifying novel applications of dialectical behavior therapy: considering emotion regulation and parenting. Curr Opin Psychol 21:122–126

Borelli JL, Margolin G, Rasmussen HF (2015) Parental overcontrol as a mechanism explaining the longitudinal association between parent and child anxiety. J Child Fam Stud 24:1559–1574

McFarlane AC (1987) Family functioning and overprotection following a natural disaster: the longitudinal effects of post-traumatic morbidity. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 21:210–218

Heft L (1993) Helping traumatized parents help their traumatized children: a protocol for running post-disaster parents groups. J Soc Behav Pers 8:149

Humphreys KL, Myint MT, Zeanah CH (2020) Increased risk for family violence during the covid-19 pandemic. Pediatrics. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-0982

Scheel MJ, Rieckmann T (1998) An empirically derived description of self-efficacy and empowerment for parents of children identified as psychologically disordered. Am J Fam Ther 26:15–27

Cunningham A, Renk K (2018) Parenting in the context of childhood trauma: self-efficacy as a mediator between attributions and parenting competence. J Child Fam Stud 27:895–906

Kövesdi A et al (2021) The role of self-efficacy in adapation regarding parental and child resilience: a longitudinal study on the two waves of covid 19. Acta Sci Neurol 4:53–62

Davidson B et al (2021) Risk and resilience of well-being in caregivers of young children in response to the covid-19 pandemic. Transl Behav Med 11:305–313

Miki T et al (2019) Impact of parenting style on clinically significant behavioral problems among children aged 4–11 years old after disaster: a follow-up study of the great east japan earthquake. Front Psychiatry 10:45

Ehrenreich-May J et al (2018) Unified protocols for the transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders in children and adolescents: therapist guide. Oxford University Press, New York

Sakiris N, Berle D (2019) A systematic review and meta-analysis of the unified protocol as a transdiagnostic emotion regulation based intervention. Clin Psychol Rev 72:101751

Farchione TJ et al (2012) Unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders: a randomized controlled trial. Behav Ther 43:666–678

Bilek EL, Ehrenreich-May J (2012) An open trial investigation of a transdiagnostic group treatment for children with anxiety and depressive symptoms. Behav Ther 43:887–897

Ehrenreich-May J, Rosenfield D, Queen AH, Kennedy SM, Remmes CS, Barlow DH (2017) An initial waitlist-controlled trial of the unified protocol for the treatment of emotional disorders in adolescents. J Anxiety Disord 46:46–55

Kennedy SM, Bilek EL, Ehrenreich-May J (2019) A randomized controlled pilot trial of the unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders in children. Behav Modif 43:330–360

Kendall PC, Norris LA, Rabner JC, Crane ME, Rifkin LS (2020) Intolerance of uncertainty and parental accommodation: promising targets for personalized intervention for youth anxiety. Curr Psychiatry Rep 22:1–8

Eisenberg N, Cumberland A, Spinrad TL (1998) Parental socialization of emotion. Psychol Inq 9:241–273

Tonarely NA, Kennedy S, Halliday ER, Sherman JA, Ehrenreich-May J (2021) Impact of youth transdiagnostic treatment on parents’ own emotional responding and socialization behaviors. J Child Fam Stud 30:1141–1155

Guzick AG et al (2022) Brief, parent-led, transdiagnostic cognitive-behavioral teletherapy for youth with emotional problems related to the covid-19 pandemic. J Affect Disord 301:130–137

Ehrenreich-May J, Halliday ER, Karlovich AR, Gruen RL, Pino AC, Tonarely NA (2021) Brief transdiagnostic intervention for parents with emotional disorder symptoms during the covid-19 pandemic: a case example. Cogn Behav Pract 28:690–700

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B (2006) A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the gad-7. Arch Intern Med 166:1092–1097

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB (2001) The phq-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 16:606–613

Blevins CA, Weathers FW, Davis MT, Witte TK, Domino JL (2015) The posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for dsm-5 (pcl-5): development and initial psychometric evaluation. J Trauma Stress 28:489–498

Malloy LC, Comer JS, Ehrenreich-May J (2020) Coronavirus/covid experiences questionnaire. Unpublished manuscript.

Norman SB, Hami Cissell S, Means-Christensen AJ, Stein MB (2006) Development and validation of an overall anxiety severity and impairment scale (oasis). Depress Anxiety 23:245–249

Campbell-Sills L et al (2009) Validation of a brief measure of anxiety-related severity and impairment: the overall anxiety severity and impairment scale (oasis). J Affect Disord 112:92–101

Bentley KH, Gallagher MW, Carl JR, Barlow DH (2014) Development and validation of the overall depression severity and impairment scale. Psychol Assess 26:815

Simons JS, Gaher RM (2005) The distress tolerance scale: development and validation of a self-report measure. Motiv Emot 29:83–102

Brown RJ, Burton AL, Abbott MJ (2022) The relationship between distress tolerance and symptoms of depression: validation of the distress tolerance scale (dts) and short-form (dts-sf). J Clin Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.23370

Leyro TM, Bernstein A, Vujanovic AA, McLeish AC, Zvolensky MJ (2011) Distress tolerance scale: a confirmatory factor analysis among daily cigarette smokers. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 33:47–57

Carleton RN, Norton MPJ, Asmundson GJ (2007) Fearing the unknown: a short version of the intolerance of uncertainty scale. J Anxiety Disord 21:105–117

Wilson EJ, Stapinski L, Dueber DM, Rapee RM, Burton AL, Abbott MJ (2020) Psychometric properties of the intolerance of uncertainty scale-12 in generalized anxiety disorder: assessment of factor structure, measurement properties and clinical utility. J Anxiety Disord 76:102309

Peterson RA, Heilbronner RL (1987) The anxiety sensitivity index: Construct validity and factor analytic structure. J Anxiety Disord 1:117–121

Reiss S, Peterson RA, Gursky DM, McNally RJ (1986) Anxiety sensitivity, anxiety frequency and the prediction of fearfulness. Behav Res Ther 24:1–8

Gibaud-Wallston J, Wandersman LP (1978) Parenting sense of competence scale. Can J Behav Sci

Hurley KD, Huscroft-D’Angelo J, Trout A, Griffith A, Epstein M (2014) Assessing parenting skills and attitudes: a review of the psychometrics of parenting measures. J Child Fam Stud 23:812–823

Gibaud-Wallston J, Wandersman LP (1978) Parenting sense of competence scale. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates

Johnston C, Mash EJ (1989) A measure of parenting satisfaction and efficacy. J Clin Child Psychol 18:167–175

Ohan JL, Leung DW, Johnston C (2000) The parenting sense of competence scale: evidence of a stable factor structure and validity. Can J Behav Sci 32:251

Rogers H, Matthews J (2004) The parenting sense of competence scale: Investigation of the factor structure, reliability, and validity for an australian sample. Aust Psychol 39:88–96

Lebowitz ER, Marin CE, Silverman WK (2019) Measuring family accommodation of childhood anxiety: Confirmatory factor analysis, validity, and reliability of the parent and child family accommodation scale–anxiety. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol

Eyberg SM, Johnson SM (1974) Multiple assessment of behavior modification with families: effects of contingency contracting and order of treated problems. J Consult Clin Psychol 42:594

Posner K et al (2008) Columbia-suicide severity rating scale (C-SSRS). Columbia University Medical Center, New York

NCTSN (2020) Parent/caregiver guide to helping families cope with the coronavirus disease 2019 (covid-19). The National Child Traumatic Stress Network

Jordan P, Shedden-Mora MC, Löwe B (2017) Psychometric analysis of the generalized anxiety disorder scale (gad-7) in primary care using modern item response theory. PloS one 12

Hox JJ, Moerbeek M, Van de Schoot R (2010) Multilevel analysis: techniques and applications. Routledge, New York

Bryk A, Raudenbush S, Congdon R (1998) Hlm4. Scientific Software International, Chicago, IL

Heck RH, Thomas SL, Tabata LN (2013) Multilevel and longitudinal modeling with IBM SPSS. Routledge, New York

Raudenbush S, Bryk A, Congdon R (2013) Hlm 7 for windows (scientific software international, skokie, il).

Seltzer M, Svartberg M (1998) The use of piecewise growth models in evaluations of interventions. Center for the Study of Evaluation

Singer JD, Willett JB, Willett JB (2003) Applied longitudinal data analysis: modeling change and event occurrence. Oxford University Press, UK

Feingold A (2009) Effect sizes for growth-modeling analysis for controlled clinical trials in the same metric as for classical analysis. Psychol Methods 14:43

Mohr DC et al (2014) Control condition design and implementation features in controlled trials: a meta-analysis of trials evaluating psychotherapy for depression. Transl Behav Med 4:407–423

Bozdağ F (2021) The psychological effects of staying home due to the covid-19 pandemic. J Gen Psychol 148:226–248

Alexander S, Pillay R, Smith B (2018) A systematic review of the experiences of vulnerable people participating in research on sensitive topics. Int J Nurs Stud 88:85–96

Preuss H, Capito K, van Eickels RL, Zemp M, Kolar DR (2021) Cognitive reappraisal and self-compassion as emotion regulation strategies for parents during covid-19: an online randomized controlled trial. Internet Interv 24:100388

Daly M, Robinson E (2021) Psychological distress and adaptation to the covid-19 crisis in the United States. J Psychiatr Res 136:603–609

Yarrington JS et al (2021) Impact of the covid-19 pandemic on mental health among 157,213 Americans. J Affect Disord 286:64–70

Boden M et al (2021) Addressing the mental health impact of covid-19 through population health. Clin Psychol Rev 85:102006

Kuehn BM (2022) Clinician shortage exacerbates pandemic-fueled “mental health crisis.” JAMA 327:2179

Terry PC, Parsons-Smith RL, Terry VR (2020) Mood responses associated with covid–19 restrictions. Front Psychol 11:3090

Tai DBG, Shah A, Doubeni CA, Sia IG, Wieland ML (2021) The disproportionate impact of covid-19 on racial and ethnic minorities in the united states. Clin Infect Dis 72:703–706

Kennedy SM, Lanier H, Salloum A, Ehrenreich-May J, Storch EA (2021) Development and implementation of a transdiagnostic, stepped-care approach to treating emotional disorders in children via telehealth. Cogn Behav Pract 28:350–363

Funding

The study was supported by the University of Miami Office of the Vice Provost for Research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Halliday, E.R., Cepeda, S.L., Grassie, H.L. et al. Initial Effects of a Brief Transdiagnostic Intervention on Parent Emotion Management During COVID-19. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 55, 372–383 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-022-01409-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-022-01409-5