Abstract

Background

Sweden is in transition when it comes to the immigrant experience. More research is needed to document the life circumstances and adjustment of those with foreign background living in Sweden.

Objective

This study investigated the lived experiences of parents of youths and young people themselves who have an Iraqi or Syrian background and are living in Sweden.

Method

This cross-sectional qualitative interview study focused on a sample of parents of youth and youth (N = 26) with a foreign background. Participants were either born in Syria or Iraq or had one or both parents born in these countries and had migrated to Sweden. Participant interviews were analyzed using thematic analysis.

Results

In relation to the study aim, the analysis indicated three main themes in participants’ responses which concerned life in Sweden, feeling at home, and coping.

Conclusions

Overall, these themes reflected how the perception of everyday experiences relates to adjustment within a multi-cultural urban Swedish context. This study showed how participants with a foreign background are rich in their own diversity of experiences and viewpoints. Results also pointed towards the promise of social policy and services aimed at benefiting those with a foreign background if such efforts are situated in the microsystems that provide life daily structure, as well as in contexts that offer socialization and networking opportunities (e.g., training, education, work, and school). Further, such action should consider the importance of the extended family as part of family-focused initiatives.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background and Research Priorities

This study concerns aspects of the Swedish immigrant experience. Countries differ in how individuals with an immigrant background are defined in population statistics. Statistics Sweden (2020) considers individuals as having a foreign background if they were either born outside of Sweden or if they were born in Sweden but both parents were born abroad. Although there have been recent increases in immigration, the immigrant experience in Sweden is not a new phenomenon (Statistics Sweden 2019). There are many with a foreign background in Sweden (Statistics Sweden 2020). In 2019, 19.6% of the Swedish population was born abroad (Statistics Sweden 2020). Also, 25.5% of Swedish children have a foreign background (Statistics Sweden 2020). For those with a foreign background, common birth countries outside Europe are Syria, Afghanistan, India, and Iraq (Statistics Sweden, 2020). Since the immigration context in Sweden varies greatly by ethnicity, population size, and immigration history, this study focused on understanding the everyday situation of only two prominent, in terms of share of the local population, immigrant groups living in a large urban city in Sweden. One group has a longer history within Sweden (e.g., Iraqi) relative to the other, which has a more recent arrival in Sweden (e.g., Syrian).

Sweden is in transition concerning public discourse and immigrant policies, practices, and services (Hodes et al. 2017). Sweden is characterized as having “…generally multicultural approaches and attitudes and most favorable integration policies, also has the child population with above-average markers of well-being” (Marks et al. 2018, p. 16). Even with a positive international standing, findings suggest that relative to children with a non-foreign background, those with a foreign background tend to live with a single parent, in a large metropolitan urban setting, and in rental housing (Statistics Sweden 2017a, b), have lower educational achievement, and are at risk of dropping out of upper secondary education (10.5% vs. 5.4%; OECD, 2014). However, many children with a foreign background also have strengths (e.g., Carlerby et al. 2012; Taguma et al. 2010). A study of 685 Swedish youth showed that those with a foreign background were more likely to plan university studies directly after high school relative to those with a non-foreign background, who were more likely to plan to work or travel before pursuing university studies (Kaya and Barmark 2018). Such educational values are consistent with the immigrant optimism hypothesis (Kaya and Barmark 2018), in which high educational aspirations are valued as key pathways to success.

Further from a theoretical standpoint, the integrative risk and resilience model for immigrant populations holds that youth with an immigrant background contend with normative challenges that all youth face, along with unique opportunities for change related to adjusting to a new society (Suárez-Orozco et al. 2018). In such circumstances, the home and wider society are essential developmental contexts, not only for youth but also for parents of youth (Suárez-Orozco et al. 2018).

Given this background, more research is needed to document the life circumstances of youth and parents of youth with a foreign background in Sweden. Some information is available from Swedish registry data (e.g., Hjern 2012; Rostila and Fritzell 2014). However, wide ranging and more detailed survey- and/or interview-based studies with parents of young people, as well as youth themselves who have a foreign background living in Sweden are few in number. Thus, it is essential to develop new knowledge about how these groups are faring in Sweden and to gain insight into participants’ perspectives, in their own words.

Empirical Studies About Iraqi and Syrian Immigration Experiences

Past qualitative studies about the immigrant experience in Sweden and elsewhere focusing on the relatively large and diverse migration groups from Syria or Iraq do exist, but have mainly explored how adults encounter medical and/or psychiatric care (e.g., Karlberg and Ringsberg 2006). However, a study of 154 Iraqi refugees who had resettled to the United States (U.S.) also included in-depth interviews with a subset of five participants (Yako and Biswas 2014). Qualitative analyses revealed that practical supports were important for transitioning to a new life in the U.S., particularly the availability of a secure and comfortable place to live, and short term financial and language support (Yako and Biswas 2014).

In the wider international literature, it is clear that work is important to adaptation and well-being among many immigrant groups in general. A Canadian study conducted by Zikic and Richardson (2016), for example, found that skilled migrants with established professions faced difficulties in understanding and overcoming institutional requirements in the labor market. Self-initiated international careers due to migration have also been found to be challenging for many across different societies in the West (e.g., Canada, Spain, France, see Zikic et al. 2010). Similar observations have been made in Sweden, highlighting the difficulties to validate ones’ competence, and thus, find qualified jobs (Diedrich and Styhre 2013). How migrants and their children experience these transitions in parents’ work has not been focused upon, in Sweden, although it can be expected that both adults and youth are affected and have their own experiences of their parent’s or child’s adaptation to a new host society.

Generally, studies about immigrants’ experiences in Sweden have often focused on ethnic identity, across diverse immigrant groups or have a focus on a particular ethnic group in Sweden, such as Swedes with an Iranian heritage. Results from such studies highlight how these groups experience and negotiate different cultural and social worlds (e.g., Ferrer-Wreder, Trost et al. 2012). In a relatively recent study, 16–29-year-olds with and without foreign backgrounds wrote narratives about their own ethnic-related experiences (Gyberg et al. 2018). Several themes, including a sense of feeling different and experiences of prejudice and racism, emerged. For foreign born participants, there was an emphasis on redefining what it means to be Swedish.

Study Aim

This study investigated the lived experiences of parents of young people (i.e., 15–16 year olds) and youth themselves who have an Iraqi or Syrian family background and are living in a large Swedish city.

Method

Participants

Participants were 15–16-year-olds and parents of 15 to 16 year olds (N = 26). Of those interviewed, 20 participants had completed a questionnaire and provided detailed demographic information. The others provided no questionnaire data and only had basic demographics recorded (See Tables 1 and 2). One interview with an adult participant (recruited via registry/mail home approach; see procedure for details about recruitment) was excluded due to transcription problems. The final sample consisted of 25 participants (15 parents of youth and 11 youth) who provided interview material that are analyzed in the present study.

Data Collection

The interviews were semi-structured and followed an interview guide developed by researchers within this project. In order to examine the lived experiences, participants were asked to describe what an ordinary day looked like, what they would like to change in their life, where they felt at home, and who they met with socially. Other questions were part of the interview guide and focused on the topic of research participation. Responses to the questions about research participation are not included in the present analyses. On average, an interview lasted 38 min (20–88 min). Interviews were digitally recorded, transcribed verbatim, and translated into English.

Procedure

This is a cross-sectional interview study that is part of a wider project. Participants that met study inclusion criteria (criteria are explained in the next paragraph) were approached through either registry-based recruitment via Statistics Sweden or community-based recruitment via research assistants who visited a range of community organizations, placed study advertisements, and used snowballing techniques. For the registry arm, the family study response rate was 11% (45 out of 400 families contacted participated in some aspect of the project). Community-based recruitment was conducted by in-person and written communications. In the community arm, the organizational response rate was 27%. The wider project, in which this interview study is embedded, was designed to test the relative utility of these two recruitment approaches (registry in comparison to community-based recruitment). Results of the wider project as it regards research participation will be reported elsewhere. The wider study procedure was to ask all participants that met the study inclusion criteria, to complete a questionnaire on health, well-being, and related topics and/or to participate in a one-on-one interview. Participants could decide to only answer the questionnaire and/or participate in the interview or both. Participants contacted through the registry received a mailed letter with information about the project from Statistics Sweden. This letter also contained the questionnaire and pre-paid envelopes to return the completed questionnaire to the research team. Participants who had indicated in the questionnaire that they were interested in being interviewed were contacted. Interviews were held in participants’ homes or community locations. Participants could choose to conduct their interview in Arabic or Swedish.

The project inclusion criteria were family-focused and involved inviting participation by youths and/or at least one parent and/or another family member (e.g., the other parent, an adult sibling, aunt, uncle, or grandparent). Study inclusion criteria for youth participants were that youth were between 15 and 16 years old and lived in a specific geographic urban region of Sweden with a large population of inhabitants born in Iraq or Syria. In Sweden, 15–16-year olds are transitioning into high school and encountering an important social and educational transition. Thus, this age range was selected for the youth participants. Other study inclusion criteria were that within the family that at least one parent was born in Iraq or Syria. Only two families had two adult informants in which fathers and mothers participated. The family-based focus of this study was not pursued in the analysis of the interviews due to the existence of only a limited number of parent–child dyads who took part in the interview. In some cases, youths would participate in the interview and not their parents and vice versa. As the overall project aimed to better understand reasons for research participation of families in social science and health studies, families were instructed that youths and/or other adult family members could participate in any part of the research project (i.e., interviews or self-report surveys). Therefore, in the present study, we analyzed the parents of youth and youth interviews in their own right and not as parent–child dyads. For the sake of brevity, from this point forward, we refer to parents of youth (i.e., parents living with their child, specifically a 15–16 year-old) as parents, noting that parent–child dyads are in the minority in the present study sample, not allowing for an analysis by parent–child dyads.

All participants provided active informed consent and this study was approved by a Regional Ethical Review Board. The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. Procedures and materials were informed by culturally sensitive research methods widely used in the international research literature dedicated to engaging underrepresented ethnocultural and/or immigrant groups in research (e.g., Aroian et al. 2006; Lee and Cheng 2006; Lopez-Class et al. 2016). This included the production of study materials in relevant languages (Arabic and Swedish) for the participants and field research assistants who were fluent in Swedish and/or Arabic. The entire research team is living in Sweden and have a foreign background but did not have the same national or ethnic heritages as study participants. However, the field research assistants had group specific cultural knowledge and sensitivity. Participants were offered culturally appropriate participant incentives (e.g., non-monetary incentives of minor but some moderate value to youths and parents, gift card for a department store or movie tickets).

Data Analysis

It is important to note that qualitative approaches look at patterns observed rather than reporting frequencies or sample sizes where acceptance can be quantified (Fugard and Potts 2015). Indeed, subjective judgement guided by the data and the research questions play an important role which can function to seek patterns. Following guidelines by Fugard and Potts (2015) looking at instances of themes in regard to questions and cohort as well as cohesive judgement and agreement between three coders, the data analyses was conducted using a thematic approach.

A thematic analysis, following the Braun and Clarke (2006, 2013) approach, was conducted by three coders who are also study authors. All study authors take responsibility for data integrity. The authors who coded the interview data take responsibility for the accuracy of the data analysis. Regarding the coding process, first, coders read all interview material to familiarize themselves with the data. The initial coding was conducted separately using an inductive bottom-up approach. Thus, all relevant data regarding lived experiences of (im)migration and participation in research studies regarding (im)migration were coded. However, the coders also worked deductively and used their disciplinary knowledge by coding patterns of agency referring to society, family, and the individual, and by coding content that revealed participants’ psychological approaches to making sense of and creating meaning for lived experiences of (im)migration. Then, the analyses, including codes and generated emerging patterns, were discussed. Differences in coding were resolved by consensus and decisions were made on preliminary themes. Following this, each coder worked through the material again, to make sure that these emerging themes fitted the essence of the coded data units and patterns in the data. In the final analytic step, results were written and reviewed to ensure that each theme of the emerging theme structure was coherent and had a clear scope, and that all themes provided a rich and meaningful picture of participants’ accounts. Illustrative quotations were given for each theme.

Results

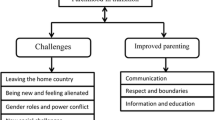

In relation to the study aim, results yielded three main themes with various sub-themes (See Table 3).

Life in Sweden

Participants’ life routines in Sweden that became evident in their day-to-day life and daily structures included six sub-themes. They were present in all interviews, but emphasized differently.

The Meaning of Work

Work was important both for parents and youth in providing structure to the weekday, or, in cases of seasonal work, the year. Work was also referred to in relation to professions and professional identities. In many families both parents worked, e.g., youth talked about their mother's and father's jobs, or parents reported on daily routines that included employment of both adults in the family. Parents also referred to their own or their partner's internship as a work activity that was expected to be a step towards employment (Table 3, Q1.1.1). For those with no paid employment, work and the absence of it was a pressing theme; several obstacles, including learning the language, doing the qualifying course, getting a residence permit, or adequate help to find a suitable job, had to be overcome. Professional identities, for example being a teacher, a dentist, having certificates in mathematical science, having worked in different professions prior to immigration were emphasized. Finding employment was considered a key to a life in Sweden, and essential for not being forced to live from benefits anymore. Emphasis on professional identity was closely linked to emphasis on a work identity, to indicate that one is used to work and is not “lazy”. In struggling families, youth were aware of, and concerned about their parents’ situation (Table 3, Q1.1.2).

School has a Central Role

All youth were at school and it structured the day and was the place to be. There was frequent mentioning of siblings being in Swedish child care or at school. School had an important role during evenings and weekends as well: homework, studying, doing work for school, preparing for tests and exams were daily activities that mainly involved youth but often their parents as well. Parents hoped that the children would succeed in education and build a good life (Table 3, Q1.2.3). This is also apparent in the youth interviews. For some, education and a future job were essential to their future economic situation. For others, school and their education was the key to everything else in life (Table 3, Q1.2.4).

Accommodation

Many families had trouble finding a suitable place to live. Mainly parents worried about their housing situation, but youth were often aware of their parents’ struggling and wished for a change (Table 3, Q1.3.5). Housing was also troublesome for those not fitting the typical average family requirements including mentioning of the difficulties to find larger accommodation and the high costs involved. Participants experienced greater vulnerability in a tight housing market with long waiting lists and requirements of having steady income (Table 3, Q1.3.6).

Social Relations

Parents and youth had social ties and daily contacts to colleagues and customers at work, friends, teachers, students at school, neighbors, and members of sport clubs, the church or mosque, or community. Particularly among youth, spending time with friends was an important part of their daily activity and life routine. A considerable amount of the study participants also had close contact to relatives in their extended families. For example, parents mentioned visiting their parents a lot, and some mentioned that their relatives and extended family were in Sweden. Youth talked about having aunts, uncles, cousins, or grandparents living close in Sweden, so that these social ties were an important part of the life routines in Sweden, with several visits during the week or at the weekend and on free days (Table 3, Q1.4.7., Q1.4.10., Q1.4.11).

Health

Health, and foremost health problems in adults, was a concern for parents and youth alike. For some, health was a prerequisite to a good life, something to appreciate because health cannot be bought (e.g., Table 3, Q1.5.12). Youth observed parent’s health issues, which they saw affected the whole family. In one case, youth believed that the mother kept her job despite no longer having the physical capacity to continue working there, and thus never had energy left for the family, not on evenings nor weekends. Also, youth mentioned parents’ mental health issues as related to problems finding work (Table 3, Q1.5.12–1.5.13). Themes of mental or physical ill-health associated with work, income, and housing, illustrate how vulnerability would accumulate for some.

Free Time

Working out physically was a frequent activity of many youth during the week and weekends. This mainly included working out at a gym, but some were training specific sports, including soccer, boxing, or wrestling. To some extent, youth activities required family engagement because parents were responsible for transporting youth to and from activities. Some parents reported weekly workouts as part of their life routines. Occasionally, other leisure activities and engagements outside of work and school were mentioned, such as playing an instrument, being a scout, or attending religious school for Arabic lessons. Parental political activities or active participation in the local housing association were described as well. Going to church or mosque or meeting friends from the church or mosque were among the activities mentioned rarely as part of the life routines (Table 3, Q1.6.14–1.6.17).

Feeling at Home

The patterns identified from parents involved characteristics that reflected the feeling of being at home as stemming from accommodation, work/school, family, and religious/cultural beliefs.

Accommodation Gives Feeling at Home

Unarguably, one of the most predominant themes in frequency from both parents and youth was the idea of accommodation. Having a place to live and a place to call their own is what many reported as being important to feeling at home. Having such a place seemed to be associated with security, a subsequent sense of being at home, and was important to participant's perceived agency (Table 3, Q2.1.1, Q2.1.2).

School and Work Gives Feeling at Home

Both parents and youth, reflected on school and work as being important not only for themselves but for others. Youth and parents mentioned school/education as being important and as a conduit that can help youth feel comfortable in a new country. Parents described school and education as necessary for their children, because this will make them feel at home and have a future in Sweden. The youth mentioned school in some way as an important aspect of their lives in terms of feeling at home. Parents and youth appeared to be keenly aware of each other’s road to feeling at home. Both work and education were often seen as a way of not having to rely on the establishment, which in turn gave some a feeling of being at home (Table 3, Q2.2.3, Q2.2.4).

Family Gives Feeling at Home

The most predominant and well represented idea across the interviews was that of family, where participants, independent of age, noted that the context of social connectedness with family gave a sense of home. Social connectedness with not only close family members but even extended family clearly was a driving agent considered to help one’s sense of being at home in another country. For instance, youth noted feeling at home is where the entire family is, including extended family. Due to having extended family abroad, Sweden was not always considered to be home (Table 3, Q2.3.5). Others had family, including extended family, in Sweden, which added to feelings of being at home (Table 3, Q2.3.6). The two perspectives exemplify the importance of extended family in the perception of feeling at home. It also questions a Westernized definition of family and extending it beyond the nuclear family when investigating the lives of immigrants. Yet, family in a more nuclear, traditionally westernized sense was mentioned as well. For some, it is indeed important to have the entire family together, while others did not mention the extended family but having everyone from the family in the same place, gives a feeling of being at home independent of place or country. Yet, other youth mentioned family as making them feel at home even when friends do not seem to exist. This is particularly interesting considering that friends play an important role in young people’s lives with respect to feeling comfortable (Table 3, Q2.3.7). A sense of feeling at home stems from the family as a very strong agent to one’s own feelings. Parents leaving to provide their children with a better, safer and more comfortable future describe how this, through the children, makes the parents feel at home (Table 3, Q2.3.8).

Religion/Belief Gives Feeling at Home

This key sub-theme refers to the individual expressing experiences of feeling at home through their relations to religion or God. Despite not being a predominant theme across the interviews, it seemed critical to those few who specifically mentioned religion as an aspect of feeling comfortable. This then, motivates its importance in the results. Religion or a commitment to religion is mentioned with regard to a feeling of security and a feeling of home (Table 3, Q2.4.9). A commitment to religion seems to function as giving and holding of traditions and practices which, in turn, give a feeling of being at home. Parents considered it important to transfer such a commitment to their children to share principles of life and involve them in traditions (Table 3, Q2.4.10).

Coping

Participants often described their current life-situation in comparison to their past, pre-migration, experiences in their home-countries or to possible future, post-migration scenarios. In these descriptions, the coping efforts with migration challenges, e.g., with the loss of any former structure and difficulties of building a new one, became visible. Youth did not evidence in their responses complex psychological structures for meaning-making about their pre-migration experience. Youth did not seem stuck in a pre-migration situation but instead they focused on adapting to a new context. However, parents in this sample brought along more complex psychological structures, which allowed them to engage in different meaning-making processes. They reveal highly individualized and creative variations in their ways of coping with the migration situation. What becomes apparent are their difficulties in leaving behind a former life-situation and their lack of attempts to adapt to the culture, ideals, and norms of the new society.

Comparing the Present to the Past

Some were living in the past, which relates to the migration having led to a severe loss with no possibility of compensation. For instance, those who had been successful in their home countries now had difficulties finding work. Thus, the current life situation was experienced as an “abnormal condition” characterized by helplessness. This unsuccessful situation was accompanied by other problems, including stress (Table 3, Q3.1.1, Q3.1.2, Q3.1.3). Helplessness was accompanied by requests for authorities or the government to “take away the hindrances for employers” in order to facilitate the possibility of employment. A strong longing for the past was also linked to a position characterized by not having psychologically arrived in Sweden. These parents seemed to focus on a (lost) situation in their pre-migration country. They were not “here”, but “there” and thus not fully present in their current life-situation.

“Escaping” Reality

The permanent concerns of every-day life about “clothes, work, children” were experienced as stressful. In contrast to a strategy where others (e.g., the country, the authorities) are made responsible for this, this stress instead involves a mental state characterized by a standstill in which nothing happens and there are no thoughts of actions. Such a tendency to escape the present reality is expressed in parents preferring not to having to think of any daily ordeals (Table 3, Q3.2.4). Such a state would then be experienced as a relief. Another strategy of escaping involves focusing on specific roles, for instance on being “a mother and … a sister to [the] siblings”. Thus, home provides a possibility to be a mother, regardless of the society in which one lives. To ignore all biographical and historical aspects allows feelings of “security”. However, there is also an awareness of the consequences associated with such a focus (Table 3, Q3.2.5, Q3.2.6). Instead of being oriented towards any past or future point in time, the individual focus involves wishing for a safe place characterized by some sort of timelessness. Such a timelessness allows little room for adaptation or for establishing meaning around the migration process and related experiences.

Loss of the Pre-Migration Life

Another pattern involves losing the “old life” in the country of origin, i.e., before the actual migration to Sweden. In the new country, the typical challenges were described as: Besides mastering the language, new relationships are considered necessary in order “to enter society”. Home was lost “when the old life had stopped” in the old country. However, here, the main fear lies in experiencing a repetition of the old societal conditions in Sweden. This fear was described to include risking to form a “society within the society”, “with the same things: persecution of the other. Racism.” In the old country, “a majority was persecuting the rest” and this may also happen in Sweden. Yet, a clear difference is emphasized: In Sweden “a law one can turn to” exists.

Positive Future for the Children

School is seen as important to ensure the future of the children. It is a clear description of a future-oriented situation where a home is a place for the children “in the future”. This place is linked to the new country and to accommodation, language, having a job, and with earning money. Although learning a new language is reported as a difficulty, the acquisition of a new language is seen as necessary. Another component needed to feel at home is feeling “comfortable”. This involves a “comfortable house, a job one feels comfortable with, and children who are comfortable”. The key to achieve this is described in terms of “strong personalities”. Instead of being afraid that the “children get lost in Sweden”, it is seen as necessary to rely on and trust the strengths of children.

Discussion

This study set out to explore the perspectives of immigrant parents and youths’ lived experience. Results indicated three main themes relevant to this study aim which concerned everyday experiences of life in Sweden, feeling at home, and coping. Considering the main themes of everyday experiences of participants —that is life in Sweden, feeling at home, and coping—these clearly revolved around issues that form part of daily life. Facing every day and normative challenges is also in line with the integrative risk and resilience model (Suárez-Orozco et al. 2018). Specifically, accommodation seemed as a prerequisite for stability. This finding is consistent with a past qualitative study of Iraqi refugees living in the U.S. (Yako and Biswas 2014), which also highlighted the importance of stable housing of appropriate size for a family as secure basis for adaptation and setting the stage for a stable and safe future.

In addition to accommodation, work and any income related to work, provides an important path into a new society for adults (e.g., Zikic and Richardson 2016). However, language and societal structures (e.g., labor market laws, rules, and regulations regarding employment and education) can constitute barriers for entering the Swedish labor market (Diedrich and Styhre 2013). In the present study, for those who worked, new jobs gave structure to daily life albeit the work may not exactly fit individuals’ education or expectations. For others, job searching activities and language courses helped to provide a structure for daily life. As is seen in international literature, work is an important lived everyday experience whether one is an adult or being the observer of the adults in their home as in the case of the youth in this study. Similar to participants in in Zikic and Richardsson’s study (2016), the parents in this study reported feeling that work and attending classes gave their everyday lives structure and meaning. Interestingly, youth in this study also reported such similar lived experiences from their parents being employed. This suggests that the type of work per se may not be the underlying factor but the embedded structure, value, and hope that it may give as attending language courses and searching for possible employment in a structured way also was quite meaningful. As a whole however, employment does seem to be perceived as important for well-being for youths and parents in this sample, which is consistent with ideas posited by Jahoda (1958).

Consistent with the immigrant optimism hypothesis (Kaya and Barmark 2018), the participants in this study, independent of cohort, emphasized the importance of education as a way to enter and thrive in the Swedish society. Similar to work structuring the day for parents, school structured the day for youth. Also, both work and school include opportunities to contact people beyond the family, thus expanding participant's social network. This structure, socialization and networking that work and school provided in the daily life of participants also is in keeping with historically important factors linked to positive functioning and health (e.g., Jahoda 1958).

In line with previous research on adjustment, participants’ ways of coping were associated with their views of their current and future situations (Heffer and Willoughby 2017). Parents with more straining life situations characterized for instance by low incomes, high insecurity, and poor working conditions, were more likely to have more difficulties in seeing a positive future for themselves and instead missed what they had before migrating. However, many of participants had hopes for the younger generation to be better off, while others, with reasonable incomes, security and better jobs, were more likely to adjust to their situation and focus on their current life in Sweden while also having hopes for the younger generation. Youth seemed well aware of adults’ daily coping, mentioning the sacrifices older generations made in order to provide youth with better future prospects. Importantly, the issues of bringing conflicts between different immigrant groups to Sweden and fearing a society within the Swedish society were mentioned by some participants. While some may prefer to stay with cultural counterparts and, for instance, maintain traditional gender roles, others may want adapt to the mainstream Swedish context. This was reflected in the different ways of coping. These variations in coping make it clear that different individuals have varied support needs for adapting to Sweden. Thus, the situation of individuals has to be carefully explored in order to offer adequate support.

The extended family including aunts, uncles, and grandparents was important. Both parents and youth mentioned the extended family emphasized the need to have all family members around to feel at home. The extended family played an important role in for instance providing support. Perhaps traditions and religion, albeit not consistent yet included in the data-material, where parents expressed concern of youth not being in line with traditional values of the pre-migration culture and religion, could be understood as a means to link back to the extended family and keep shared values across generations. More consistent, however, was the conceptualization of “family” being more than just the immediate nuclear family.

There was no consistent mentioning of prejudice or racism found in some previous research (cf. Gyberg et al. 2018). This may relate to the present study focusing on everyday experiences. So, while not disputing the fact that prejudice and racism are part of daily life, the interviews may not have prompted this topic for these study participants. Most of the information did involve encountering and making the Swedish context one’s own place at the individual level or concerned “micro-systems” (Suárez-Orozco et al. 2018) including schools, neighborhoods, or families. Thus, any micro level context action may improve the “immigration receiving contexts” (e.g., Marks et al. 2018). With everyday issues situated within microsystems, interventions based in key micro-systems and/or tailoring of resources in schools, neighborhoods, and homes may be effective. Yet, the importance of extended family was emphasized as a key factor, meaning that actions addressing the extended family may be valuable. However, the present findings should be viewed as tentative and awaiting further replication prior to action or policy based on the present study themes concerning migration within Sweden.

Regarding study limitations it is recognized that individuals are unique in their lived experiences and the present findings are relevant to this sample and may not generalize further to all with a foreign background; nor do we generalize the findings to immigrants from the two specific countries who live in Sweden. It was determined that 25 interviews were sufficient to understand the unique but everyday experiences of the participants. Yet, additional participants would improve representativeness. We analyzed parents and youth separately and not as parent–child dyads due to a lack of family dyads participating in the interview study. If dyads were available, linking parents with their children may have revealed dyadic themes regarding for instance coping within families but generalizing findings would still be cautioned. Similarly, any in-depth analysis concerning gender may have produced other themes than those presented here.

In relation to study strengths, these results begin to address empirical gaps in the research literature on the immigrant experience in Sweden among parents and youth at key social and cultural transition points (i.e., the transition to high school). These findings also provide directions for future research. Considering past and present life conditions of parents and youth, their current everyday routines, characteristics of feeling at home, and coping are important. Future research would benefit from considering the diversity of experiences of individuals with immigrant backgrounds, including their different coping strategies and how they encounter the mainstream/receiving and heritage cultures, and to focus on the microsystems that are important for everyday life. Since 25.5% of population in Sweden have a foreign background (Statistics Sweden 2020), it is important to understand that the population in Sweden is diverse, culturally and linguistically. Consistent with Suárez-Orozco and colleagues (2018) integrative risk and resilience model for immigrant populations, the present study results also illustrate that how those with a foreign background are rich in their own diversity of experiences and viewpoints. Yet, at the same time, study participants also shared several normative challenges and everyday life experiences that are also commonly encountered by Swedes without a foreign background (Suárez-Orozco et al. 2018). Research that simultaneously studies these complex processes is a needed next step to understanding diverse populations.

Change history

06 November 2020

The original version is updated due to the blinded contents missed to remove.

References

Aroian, K. J., Katz, A., & Kulwicki, A. (2006). Recruiting and retaining Arab muslim mothers and children for research. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 38, 255–261. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.2006.00111.x

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in Psychology, 3, 77–101.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research—a practical guide for beginners. London: Sage.

Carlerby, H., Englund, E., Viitasara, E., Knutsson, A., & Gådin, K. G. (2012). Risk behaviour, parental background, and wealth: A cluster analysis among Swedish boys and girls in the HBSC study. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 40, 368–376. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494812449926

Diedrich, A., & Styhre, A. (2013). Constructing the employable immigrant: The uses of validation practices in Sweden. Ephemera: Theory and Politics in Organizations, 13, 759–783.

Ferrer-Wreder, L., Trost, K., Lorente, C. C., & Mansoory, S. (2012). Personal and ethnic identity in Swedish adolescents and emerging adults. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 138, 61–86.

Fugard, A. J. B., & Potts, H. W. W. (2015). Supporting thinking on sample sizes for thematic analyses: A quantitative tool. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 18, 669–684. https://doi.org/10.1050/13645579.2015.1005453

Gyberg, F., Frisén, A., Syed, M., Wängqvist, M., & Svensson, Y. (2018). “Another kind of swede”: Swedish youth’s ethnic identity narratives. Emerging Adulthood, 6, 17–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696817690087

Heffer, T., & Willoughby, T. (2017). A count of coping strategies: A longitudinal study investigating an alternative method to understanding coping and adjustment. PLoS ONE, 12(10), e0186057. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0186057

Hjern, A. (2012). Migration and public health: Health in Sweden: The national public health report 2012. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 40, 255–267. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494812459610

Hodes, M., Vasquez, M. M., Anagnostopoulos, D., Triantafyllou, K., Abdelhady, D., Weiss, K., & Skokauskas, N. (2017). Refugees in Europe: National overviews from key countries with a special focus on child and adolescent mental health. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 27, 389–399. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-017-1094-8

Jahoda, M. (1958). Current concepts of positive mental health. New York: Basic Books.

Karlberg, G. L., & Ringsberg, K. C. (2006). Experiences of oral health care among immigrants from Iran and Iraq living in Sweden. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 1, 120–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482620600679688

Kaya, G., & Barmark, M. (2018). Traditional versus experimental pathways to university: Educational aspirations among young swedes with and without an immigrant background. Journal of Youth Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2018.1548759

Lee, S.-K., & Cheng, Y.-Y. (2006). Reaching Asian Americans: Sampling strategies and incentives. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 8, 245–250.

Lopez-Class, M., Cubbins, L., & Loving, A. M. (2016). Considerations of methodological approaches in the recruitment and retention of immigrant participants. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 3, 267–280. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-015-0139-2

Marks, A. K., McKenna, J. L., & Garcia Coll, C. (2018). National immigration receiving contexts: A critical aspect of native-born, immigrant, and refugee youth well-being. European Psychologist, 23, 6–20. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000311

OECD (2014). Finding the way: A discussion of the Swedish migrant integration system. Retrieved from www.oecd.org/migration/swedish-migrant-intergation-system.pdf.

Rostila, M., & Fritzell, J. (2014). Mortality differentials by immigrant groups in Sweden: The contribution of socioeconomic position. American Journal of Public Health, 104, 686–695.

Statistics Sweden (2017a). Statistical database, number of persons by region, foreign/Swedish background and year - 2016. Retrieved from https://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/pxweb /en/ssd/ ?rxid=86abd797-7854-4564-9150-c9b06ae3ab07.

Statistics Sweden (2017b). Different living conditions for children with Swedish and with foreign background - Statistical news from Statistics Sweden. Retrieved from https://www.scb.se/en/ finding-statistics/statistics-by-subject-area/living-conditions/living-conditions/children-and-their-families/pong/statistical-news/statistics-on-children-and-their-families/.

Statistics Sweden (2019). Summary of Population Statistics 1960–2018. Retrieved from: https://www.scb.se/be0101-en.

Statistics Sweden (2020). Statistical database, number of persons by region, foreign/Swedish background and year – first six months of 2020. Retrieved from https://scb.se/hitta-statistik/statistik-efter-amne/befolkning/befolkningens-sammansattning/befolkningsstatistik/.

Suárez-Orozco, C., Motti-Stefanidi, F., Marks, A., & Katsiaficas, D. (2018). An integrative risk and resilience model for understanding the adaptation of immigrant-origin children and youth. American Psychologist, 73, 781–796. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000265

Taguma, M., Kim, M., Brink, S., & Teltemann, J. (2010). OECD Reviews of Migrant Education Sweden. Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/sweden/44862803.pdf.

Yako, R. M., & Biswas, B. (2014). “We came to this country for the future of our children. We have no future”: Acculturative stress among Iraqi refugees in the United States. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 38, 133–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2013.08.003

Zikic, J., Bonache, J., & Cerdin, J. (2010). Crossing national boundaries: A typology of qualified immigrants’ career orientations. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 31, 667–686.

Zikic, J., & Richardson, J. (2016). What happens when you can’t be who you are: Professional identity at the institutional periphery. Human Relations, 69, 139–168.

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank the youth and adults who took part in this study and who made this work possible.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Stockholm University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. The program of research that this study is embedded in was funded by Stockholm County Council and Stockholm University (#4930825, #1485108).

Informed Consent

All participants provided active informed consent and this study was approved by a Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm (Ref 2016/483-31/5).

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ferrer-Wreder, L., Bernhard-Oettel, C., Trost, K. et al. Exploring Lived Experiences of Parents of Youth and Youth with a Foreign Background in Sweden. Child Youth Care Forum 50, 453–470 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-020-09583-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-020-09583-0