Abstract

Purpose

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) derived from mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) play important roles in the reduction of inflammation in multiple disease models. However, their role in vein graft (VG) remodeling is undefined. We aimed to investigate the effect of EVs from adipose MSCs (ADMSC-EVs) on VG intimal hyperplasia and to explore the possible mechanisms.

Methods

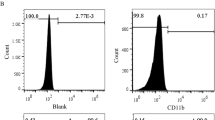

After generation and characterization of control-EVs and ADMSC-EVs in vitro, we investigated their effect on the proliferation and migration of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) in vitro. Next, we established a mouse model of VG transplantation. Mice underwent surgery and received control-EVs or ADMSC-EVs by intraperitoneal injection every other day for 20 days. VG remodeling was evaluated after 4 weeks. We also assessed the effect of ADMSC-EVs on macrophage migration and inflammatory cytokine expression.

Results

Significant inhibitory effects of ADMSC-EVs on in vitro VSMC proliferation (p < 0.05) and migration (p < 0.05) were observed compared with control-EVs. The extent of intimal hyperplasia was significantly decreased in ADMSC-EV-treated mice compared with control-EV-treated mice (26 ± 8.4 vs. 45 ± 9.0 μm, p < 0.05). A reduced presence of macrophages was observed in ADMSC-EV-treated mice (p < 0.05). Significantly decreased expression of inflammatory cytokines interleukin (IL)-6 and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) was also found in the ADMSC-EV-treated group (both p < 0.05). In addition, phosphorylation of Akt, Erk1/2, and p38 in VGs was decreased in the ADMSC-EV-treated group.

Conclusions

We demonstrated that ADMSC-EVs exert an inhibitory effect on VG neointima formation by regulating VSMC proliferation and migration, macrophage migration, inflammatory cytokine expression, and the related signaling pathways.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Bhasin M, Huang Z, Pradhan-Nabzdyk L, Malek JY, LoGerfo PJ, Contreras M, et al. Temporal network based analysis of cell specific vein graft transcriptome defines key pathways and hub genes in implantation injury. PLoS One. 2012;7, e39123.

Newby AC, Zaltsman AB. Molecular mechanisms in intimal hyperplasia. J Pathol. 2000;190(3):300–9.

Kim J, Zhang L, Peppel K, Wu JH, Zidar DA, Brian L, et al. Beta-arrestins regulate atherosclerosis and neointimal hyperplasia by controlling smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration. Circ Res. 2008;103(1):70–9.

Kumar AH, Metharom P, Schmeckpeper J, Weiss S, Martin K, Caplice NM. Bone marrow-derived CX3CR1 progenitors contribute to neointimal smooth muscle cells via fractalkine CX3CR1 interaction. FASEB J. 2010;24(1):81–92.

Yokoi H, Yamada H, Tsubakimoto Y, Takata H, Kawahito H, Kishida S, et al. Bone marrow AT1 augments neointima formation by promoting mobilization of smooth muscle progenitors via platelet-derived SDF-1{alpha}. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30(1):60–7.

Prockop DJ. Marrow stromal cells as stem cells for nonhematopoietic tissues. Science. 1997;276(5309):71–4.

Zuk PA, Zhu M, Mizuno H, Huang J, Futrell JW, Katz AJ, et al. Multilineage cells from human adipose tissue: implications for cell-based therapies. Tissue Eng. 2001;7(2):211–28.

Lee OK, Kuo TK, Chen WM, Lee KD, Hsieh SL, Chen TH. Isolation of multipotent mesenchymal stem cells from umbilical cord blood. Blood. 2004;103(5):1669–75.

Prockop DJ, Oh JY. Mesenchymal stem/stromal cells (MSCs): role as guardians of inflammation. Mol Ther. 2012;20(1):14–20.

Hoogduijn MJ, Popp F, Verbeek R, Masoodi M, Nicolaou A, Baan C, et al. The immunomodulatory properties of mesenchymal stem cells and their use for immunotherapy. Int Immunopharmacol. 2010;10(12):1496–500.

Gyorgy B, Szabo TG, Pasztoi M, Pal Z, Misjak P, Aradi B, et al. Membrane vesicles, current state-of-the-art: emerging role of extracellular vesicles. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68(16):2667–88.

Bruno S, Grange C, Collino F, Deregibus MC, Cantaluppi V, Biancone L, et al. Microvesicles derived from mesenchymal stem cells enhance survival in a lethal model of acute kidney injury. PLoS One. 2012;7(3), e33115.

Gatti S, Bruno S, Deregibus MC, Sordi A, Cantaluppi V, Tetta C, et al. Microvesicles derived from human adult mesenchymal stem cells protect against ischaemia-reperfusion-induced acute and chronic kidney injury. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26:1474–83.

Bruno S, Grange C, Deregibus MC, Calogero RA, Saviozzi S, Collino F, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived microvesicles protect against acute tubular injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20(5):1053–67.

Zhu YG, Feng XM, Abbott J, Fang XH, Hao Q, Monsel A, et al. Human mesenchymal stem cell microvesicles for treatment of Escherichia coli endotoxin-induced acute lung injury in mice. Stem Cells. 2014;32(1):116–25.

Bourin P, Peyrafitte JA, Fleury-Cappellesso S. A first approach for the production of human adipose tissue-derived stromal cells for therapeutic use. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;702:331–43.

Ratajczak J, Miekus K, Kucia M, Zhang J, Reca R, Dvorak P, et al. Embryonic stem cell-derived microvesicles reprogram hematopoietic progenitors: evidence for horizontal transfer of mRNA and protein delivery. Leukemia. 2006;20(5):847–56.

Ray JL, Leach R, Herbert JM, Benson M. Isolation of vascular smooth muscle cells from a single murine aorta. Methods Cell Sci. 2001;23(4):185–8.

Garg N, Goyal N, Strawn TL, Wu J, Mann KM, Lawrence DA, et al. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 and vitronectin expression level and stoichiometry regulate vascular smooth muscle cell migration through physiological collagen matrices. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8(8):1847–54.

Zou Y, Dietrich H, Hu Y, Metzler B, Wick G, Xu Q. Mouse model of venous bypass graft arteriosclerosis. Am J Pathol. 1998;153(4):1301–10.

Ji Y, Strawn TL, Grunz EA, Stevenson MJ, Lohman AW, Lawrence DA, et al. Multifaceted role of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in regulating early remodeling of vein bypass grafts. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31(8):1781–7.

Yanez-Mo M, Siljander PR, Andreu Z, Zavec AB, Borras FE, Buzas EI, et al. Biological properties of extracellular vesicles and their physiological functions. J Extracell Vesicles. 2015;4:27066.

Schwartz SM. Smooth muscle migration in atherosclerosis and restenosis. J Clin Invest. 1997;100(11 Suppl):S87–9.

Berk BC. Vascular smooth muscle growth: autocrine growth mechanisms. Physiol Rev. 2001;81(3):999–1030.

Hoch JR, Stark VK, van Rooijen N, Kim JL, Nutt MP, Warner TF. Macrophage depletion alters vein graft intimal hyperplasia. Surgery. 1999;126(2):428–37.

Stark VK, Warner TF, Hoch JR. An ultrastructural study of progressive intimal hyperplasia in rat vein grafts. J Vasc Surg. 1997;26(1):94–103.

Wainwright CL, Miller AM, Wadsworth RM. Inflammation as a key event in the development of neointima following vascular balloon injury. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2001;28(11):891–5.

Muto A, Model L, Ziegler K, Eghbalieh SD, Dardik A. Mechanisms of vein graft adaptation to the arterial circulation: insights into the neointimal algorithm and management strategies. Circ J. 2010;74(8):1501–12.

Xiang S, Dong NG, Liu JP, Wang Y, Shi JW, Wei ZJ, et al. Inhibitory effects of suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 on inflammatory cytokine expression and migration and proliferation of IL-6/IFN-gamma-induced vascular smooth muscle cells. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technol Med Sci. 2013;33(5):615–22.

Kim WJ, Chereshnev I, Gazdoiu M, Fallon JT, Rollins BJ, Taubman MB. MCP-1 deficiency is associated with reduced intimal hyperplasia after arterial injury. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;310(3):936–42.

Mitra AK, Gangahar DM, Agrawal DK. Cellular, molecular and immunological mechanisms in the pathophysiology of vein graft intimal hyperplasia. Immunol Cell Biol. 2006;84(2):115–24.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding Support

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of the Shanghai Municipal Government (13AR1459200).

Additional information

Rong Liu and Hong Shen contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Figure S1

EMPs are taken up by murine vessel. A, PKH26-labeled MVs (20 μg in 150 μL M-199 medium) or vehicle was injected intraperitoneally into C57BL/6 mice. After 30 min, the animals were euthanized. En face staining of aortic endothelium showed the internalization of MVs (red) into the murine vessel. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Magnification, ×200. B, Murine carotid arteries were isolated and perfused with PKH26-labeled EMPs for 30 min. After washing, PKH26-labeled EMPs (red spots) were detectable in cross-sections from EMP-perfused carotid arteries. Perfusion with M-199 served as control. Bar in cross-section pictures, 100 μm. Bar in cutouts, 50 μm. (GIF 23 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, R., Shen, H., Ma, J. et al. Extracellular Vesicles Derived from Adipose Mesenchymal Stem Cells Regulate the Phenotype of Smooth Muscle Cells to Limit Intimal Hyperplasia. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 30, 111–118 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10557-015-6630-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10557-015-6630-5