Abstract

Objective

The Intensity of Treatment Rating (ITR) Scale condenses treatment and clinical characteristics into a single measure to study treatment effects on downstream health outcomes across cancer types. This rating was originally developed for clinicians to determine from medical charts. However, large studies are often unable to access medical charts for all study participants. We developed and tested a method of estimating treatment intensity (TI) using cancer registry and patient self-reported data.

Methods

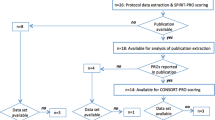

We estimated two versions of TI for a cohort of pediatric cancer survivors—one utilized information solely available from cancer registry variables (TIR) and the other included registry and self-reported information (TIS) from survey participants. In a subset of cases (n = 135) for whom the gold standard TI (TIC) was known, both TIR and TIS were compared to TIC by calculating percent agreement and weighted Cohen’s kappa, overall and within cancer subtypes.

Results

In comparison to TIC, 71% of TI scores from both methods were in agreement (k = 0.61 TIR/0.54 TIS). Among subgroups, agreement ranged from lowest (46% TIR/39% TIS) for non-defined tumors (e.g., “Tumor-other”), to highest (94% TIR/94% TIS) for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

Conclusions

We developed a methodology to estimate TI for pediatric cancer research when medical chart review is not possible. High reliability was observed for ALL, the most common pediatric cancer. Additional validation is needed among a larger sample of other cancer subgroups. The ability to estimate TI from cancer registry data would assist with monitoring effects of treatment during survivorship in registry-based epidemiological studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Kazak AE, Hocking MC, Ittenbach RF et al (2012) A revision of the intensity of treatment rating scale: classifying the intensity of pediatric cancer treatment. Pediatr Blood Cancer 59:96–99

Milam JE, Meeske K, Slaughter RI et al (2015) Cancer-related follow-up care among Hispanic and non-Hispanic childhood cancer survivors: the Project Forward study: follow-up care among cancer survivors. Cancer 121:605–613

Kadan-Lottick NS, Robison LL, Gurney JG et al (2002) Childhood cancer survivors' knowledge about their past diagnosis and treatment: childhood Cancer Survivor Study. JAMA 287:1832–1839

Wartenberg D, Groves FD, Adelman AS (2008) Acute lymphoblastic leukemia: epidemiology and etiology. Springer, Acute leukemias, pp 77–93

Milam J, Slaughter R, Meeske K et al (2016) Substance use among adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Psycho - Oncology 25:1357

Miller KA, Wojcik KY, Ramirez CN et al (2017) Supporting long-term follow-up of young adult survivors of childhood cancer: correlates of healthcare self-efficacy. Pediatr Blood Cancer 64:358–363

Bitsko MJ, Cohen D, Dillon R, Harvey J, Krull K, Klosky JL (2016) Psychosocial late effects in pediatric cancer survivors: a Report From the Children's Oncology Group. Pediatr Blood Cancer 63:337–343

Wettergren L, Kent EE, Mitchell SA et al (2017) Cancer negatively impacts on sexual function in adolescents and young adults: the AYA HOPE study. Psycho-Oncology 26:1632–1639

Gardner MH, Mrug S, Schwebel DC, Phipps S, Whelan K, Madan-Swain A (2017) Benefit finding and quality of life in caregivers of childhood cancer survivors the moderating roles of demographic and psychosocial factors. Cancer Nurs 40:E28–E37

Tobin J, Allem JP, Slaughter R, Unger JB, Hamilton AS, Milam JE (2018) Posttraumatic growth among childhood cancer survivors: associations with ethnicity, acculturation, and religious service attendance. J Psychosoc Oncol 36:175–188

Germann JN, Leonard D, Heath CL, Stewart SM, Leavey PJ (2018) Hope as a predictor of anxiety and depressive symptoms following pediatric cancer diagnosis. J Pediatr Psychol 43:152–161

Ritt-Olson A, Miller K, Baezconde-Garbanati L et al (2018) Depressive symptoms and quality of life among adolescent and young adult cancer survivors: impact of gender and latino culture. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol 7:384–388

Sleight AG, Ramirez CN, Miller KA, Milam JE (2019) Hispanic orientation and cancer-related knowledge in childhood cancer survivors. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol 8(3):363–367

Cousineau MR, Kim SE, Hamilton AS, Miller KA, Milam J (2019) Insurance coverage, and having a regular provider, and utilization of cancer follow-up and noncancer health care among childhood cancer survivors. Inquiry. 56:0046958018817996

Miller KA, Ramirez CN, Wojcik KY et al (2018) Prevalence and correlates of health information-seeking among Hispanic and non-Hispanic childhood cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 26:1305–1313

Hsiao CC, Chiou SS, Hsu HT, Lin PC, Liao YM, Wu LM (2018) Adverse health outcomes and health concerns among survivors of various childhood cancers: perspectives from mothers. Eur J Cancer Care 27:e12661

Funding

The collection of cancer incidence data used in this study was supported by the California Department of Public Health pursuant to California Health and Safety Code Section 103885; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Program of Cancer Registries, under cooperative agreement 5NU58DP003862-04/DP003862; the National Cancer Institute's Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program under contract HHSN261201000035C awarded to the University of Southern California, and contract HHSN261201000034C awarded to the Public Health Institute. This work was supported by the Whittier Foundation and Grant 1R01MD007801 from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health. Additional support was provided by P30CA014089 and T32CA009492 from the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tobin, J.L., Thomas, S.M., Freyer, D.R. et al. Estimating cancer treatment intensity from SEER cancer registry data: methods and implications for population-based registry studies of pediatric cancers. Cancer Causes Control 31, 881–890 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-020-01328-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-020-01328-7