Abstract

Purpose

Because intimate partner violence (IPV) may disproportionately impact women’s quality of life (QOL) when undergoing cancer treatment, women experiencing IPV were hypothesized to have (a) more symptoms of depression or stress and (b) lower QOL as measured with the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT-B) and Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy—Spiritual Well-being (FACIT-SP) Scales relative to those never experiencing IPV.

Methods

Women, aged 18–79, who were included in one of two state cancer registries from 2009 to 2015 with a recent incident, primary, invasive biopsy-confirmed cancer diagnosis were recruited and asked to complete a phone interview, within 12 months of diagnosis. This interview measured IPV by timing (current and past) and type (physical, sexual, psychological), socio-demographics, and health status. Cancer registries provided consenting women’s cancer stage, site, date of diagnosis, and age.

Results

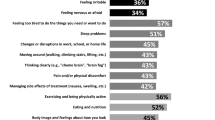

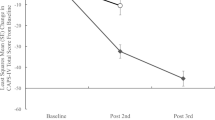

In this large cohort of 3,278 women who completed a phone interview, 1,221 (37.3%) disclosed lifetime IPV (10.6% sexual, 24.5% physical, and 33.6% psychological IPV). Experiencing IPV (particularly current IPV) was associated with poorer cancer-related QOL defined as having more symptoms of depression and stress after cancer diagnosis and lower FACIT-SP and FACT scores than women not experiencing IPV and controlling for confounders including demographic factors, cancer stage, site, and number of comorbid conditions. Current IPV was more strongly associated with poorer QOL. When compared with those experiencing past IPV (and no IPV), women with cancer who experienced current IPV had significantly higher depression and stress symptoms scores and lower FACIT-SP and FACT-G scores indicating poorer QOL for all domains. While IPV was not associated with being diagnosed at a later cancer stage, current IPV was significantly associated with having more than one comorbid physical conditions at interview (adjusted rate ratio = 1.35; 95% confidence interval 1.19–1.54) and particularly for women diagnosed with cancer when <55 years of age.

Conclusions

Current and past IPV were associated with poorer mental and physical health functioning among women recently diagnosed with cancer. Including clinical IPV screening may improve women’s cancer-related QOL.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Logan TK, Walker R, Jordan CE et al (2006) Women and victimization: contributing factors, interventions, and implications. American Psychological Association, Washington

Coker AL, Williams C, Follingstad D et al (2011) Psychological, reproductive and maternal health, behavioral and economic impact. In: White JW, Koss MP, Kazdin AE (eds) Violence against women and children: consensus, critical analyses, and emergent priorities. Volume I: mapping the terrain. American Psychological Association, Washington, pp 265–284

Modesitt SC, Gambrell AC, Cottrill HM et al (2006) Adverse impact of a history of violence for women with breast, cervical, endometrial, or ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol 107:1330–1336

Coker AL, Follingstad D, Garcia LS et al (2012) Association of intimate partner violence and childhood sexual abuse with cancer-related well-being in women. J Women’s Health 21:1180–1188

Breiding MJ, Basile KC, Smith SG, Black MC, Mahendra RR (2015) Intimate partner violence surveillance: uniform definitions and recommended data elements, version 2.0. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta. http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/ipv/intimatepartnerviolence.pdf

Black MC, Basile KC, Breiding MJ et al (2011) The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NIDVS): 2010 summary report. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta

Coker AL, Hopenhayn C, DeSimone CP, Bush HM, Crofford L (2009) Violence against women raises risk of cervical cancer. J Women’s Health 18(8):1179–1185

Golding JM (1999) Intimate partner violence as a risk factor for mental disorders: a meta-analysis. J Fam Viol 14:99–132

Baum A, Trevino LA, Dougall AJL (eds) (2011) Stress and cancers. Springer, New York

Satin JR, Linden W, Phillips MJ (2009) Depression as a predictor of disease progression and mortality in cancer patients: a meta-analysis. Cancer 115:5349–5361

Denaro N, Tomasello L, Russi EG (2014) Cancer and stress: what’s matters? From epidemiology: the psychologist and oncologist point of view. J Cancer Ther Res 3:1–11

Afifi TO, MacMillan HL, Boyle M, Cheung K, Taillieu T, Turner S, Sareen J (2016) Child abuse and physical health in adulthood. Health Rep 27(3):10–18

Hathaway JE, Mucci LA, Silverman JG et al (2000) Health status and health care use of Massachusetts women reporting partner abuse. Am J Prev Med 19:302–307

Thananowan N, Vongsirimas N (2016) Factors mediating the relationship between intimate partner violence and cervical cancer among Thai women. J Interpers Violence 31(4):715–731. doi:10.1177/0886260514556108

Farley MS, Golding JA, Minkoff JR (2002) Is a history of trauma associated with a reduced likelihood of cervical cancer screening? J Fam Pract 51:827–831

Loxton D, Powers J, Schofield M et al (2009) Inadequate cervical cancer screening among mid-aged Australian women who have experienced partner violence. Prev Med 48:184–188

Gandhi S, Rovi S, Vega M, Johnson MS, Ferrante J, Chen P-H (2010) Intimate partner violence and cancer screening among urban minority women. J Am Board Fam Med 23(3):343–353. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2010.03.090124

Brown MJ, Weitzen S, Lapane KL (2013) Association between intimate partner violence and preventive screening among women. J Women’s Health 22(11):947–952. doi:10.1089/jwh.2012.4222

Lemon SC, Verhoek-Oftedahl W, Donnelly EF (2002) Preventive healthcare use, smoking, and alcohol use among Rhode Island women experiencing intimate partner violence. J Women’s Heath 11(6):555–562

Coker AL, Bond SM, Pirisi LA (2006) Life stressors are an important reason for women discontinuing follow-up care for cervical neoplasia. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers 15:321–325

Martino MA, Balar A, Cragun JM et al (2005) Delay in treatment of invasive cervical cancer due to intimate partner violence. Gynecol Oncol 99:507–509

Kimerling R, Alvarez J, Pavao J et al (2009) Unemployment among women examining the relationship of physical and psychological intimate partner violence and posttraumatic stress disorder. J Interpers Violence 24:450–463

Coker AL, Smith PH, Thompson MP et al (2002) Social support protects against the negative effects of partner violence on mental health. J Women’s Health 11:465–476

Curry MA, Hassouneh-Phillips D et al (2001) Abuse of women with disabilities—an ecological model and review. Violence Against Women 7:60–79

Pinquart M, Duberstein PR (2010) Depression and cancer mortality: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med 40:1797–1810

Campbell JC, Kub J, Belknap RA et al (1997) Predictors of depression in battered women. Violence Victims 3:271–293

Johnson W, Pieters HC (2016) Intimate partner violence among women diagnosed with cancer. Cancer Nurs 39(2):87–96

Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB (1996) The revised conflict tactics scales: development and preliminary psychometric data. J Fam Issues 17:283–316

Follingstad DR (2011) A measure of severe psychological abuse normed on a nationally representative sample. J Interpers Violence 26:1194–1214

Follingstad DR, Coker AL, Lee E, Willimas CM, Bush HM, Mendiondo MM (2015) Validity and psychometric properties of the measure of psychologically abusive behaviors among young women and women in distressed relationships. Violence Against Women 21(7):875–896

Bonomi AE, Anderson ML, Reid RJ, Carrett D, Fishman PA, Rivara FP, Thompson RS (2007) Intimate partner violence in older women. Gerontologist 47(1):34–41

Smith PH, Earp JA, DeVellis R (1995) Measuring battering: development of the Women’s Experience With Battering (WEB) Scale. Women’s Health 1:273–288

Derogatis LR, Lazarus L (2001) Brief symptom inventory 18: administration, scoring and procedures manual. NCS Pearson, Inc., Minneapolis, MN

Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R (1983) A Global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav 24:385–396

Peterman AH, Fitchett G, Brady MJ et al (2002) Measuring spiritual well-being in people with cancer: the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual Well-being Scale (FACIT-Sp). Ann Behav Med 24:49–58

Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G et al (1993) The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy Scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol 11:570–579

Rabin RF, Jennings JM, Campbell JC et al (2009) Intimate partner violence screening tools. Am J Prev Med 36:439–445

Coker AL, Follingstad DR, Garcia LS, Bush HM (2016) Partner interfering behaviors affecting cancer quality of life. Psycho-oncology. doi:10.1002/pon.4157

MacMillan HL, Wathen CN, Jamieson E et al (2009) Screening for intimate partner violence in health care settings: a randomized trial. JAMA 302:493–501

McFarlane JM, Groff JY, O’Brien JA et al (2006) Secondary prevention of intimate partner violence: a randomized controlled trial. Nurs Res 55:52–61

Institute of Medicine (2011) Clinical preventive services for women: closing the gaps. The National Academies Press, Washington

Moyer VA, Force UPST (2013) Screening for intimate partner violence and abuse of elderly and vulnerable adults: U.S. preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 158:1–28

McFarlane J, Malecha A, Gist J et al (2002) An intervention to increase safety behaviors of abused women—results of a randomized clinical trial. Nurs Res 51:347–354

Cesario SK, McFarlane J, Nava A et al (2013) Linking cancer and intimate partner violence: the importance of screening women in the Oncology setting. Clin J Oncol Nurs 18:65–73

Acknowledgements

This paper reflects results obtained from a study funded by NIH 5R01MD004598.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

No competing financial interests exist.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Coker, A.L., Follingstad, D.R., Garcia, L.S. et al. Intimate partner violence and women’s cancer quality of life. Cancer Causes Control 28, 23–39 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-016-0833-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-016-0833-3