Abstract

Background

While high-risk geographic clusters of cervical cancer mortality have previously been assessed, factors associated with this geographic patterning have not been well studied. Once these factors are identified, etiologic hypotheses and targeted population-based interventions may be developed and lead to a reduction in geographic disparities in cervical cancer mortality.

Methods

The authors linked multiple data sets at the county level to assess the effects of social domains, behavioral risk factors, local physician and hospital availability, and Chlamydia trachomatis infection on overall spatial clustering and on individual clusters of cervical cancer mortality rates in 2000–2004 among 3,105 US counties in the 48 states and the District of Columbia.

Results

During the study period, a total of 19,898 cervical cancer deaths occurred in women aged 20 and older. The distributions of county-level characteristics indicated wide ranges in social domains measured by demographics and socioeconomic status, local health care resources, and the rate of chlamydial infection. We found that overall geographic clustering of increased cervical cancer mortality was related to the high proportion of black population, low socioeconomic status, low Papanicolaou test rate, low health care coverage, and the high chlamydia rate; however, unique characteristics existed for each individual cluster, and the Appalachian cluster was not related to a high proportion of black population or to chlamydia rates.

Discussion

This study indicates that local social domains, behavioral risk, and health care sources are associated with geographic disparities in cervical cancer mortality rates. The association between the chlamydia rate and the cervical cancer mortality rate may be confounded by other factors known to be a risk for cervical cancer mortality, such as the infection with human papillomavirus. The findings will help cancer researchers examine etiologic hypotheses and develop tailored, cluster-specific interventions to reduce cervical cancer disparities.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2006 (2008) National Cancer Institute, Bethesda. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2006/, based on November 2008 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, 2009

US Department of Health, Human Services (2000) Healthy People 2010. Understanding and improving health, vol 2, 2nd edn. US Government Printing Office, Washington, DC, pp 3–13

Singh GK, National Cancer Institute (US) (2003) Area socioeconomic variations in US cancer incidence, mortality, stage, treatment, and survival, 1975–1999. US Dept. of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda

Ward E, Jemal A, Cokkinides V et al (2004) Cancer disparities by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. CA Cancer J Clin 54:78–93

Singh GK, Miller BA, Hankey BF, Edwards BK (2004) Persistent area socioeconomic disparities in US incidence of cervical cancer, mortality, stage, and survival, 1975–2000. Cancer 101:1051–1057

Krieger N, Chen JT, Waterman PD, Rehkopf DH, Subramanian SV (2005) Painting a truer picture of US socioeconomic and racial/ethnic health inequalities: the Public Health Disparities Geocoding Project. Am J Public Health 95:312–323

Yabroff KR, Lawrence WF, King JC et al (2005) Geographic disparities in cervical cancer mortality: what are the roles of risk factor prevalence, screening, and use of recommended treatment? J Rural Health 21:149–157

Freeman HP, Wingrove BK (2005) Excess cervical cancer mortality: a marker for low access to health care in poor communities. National Cancer Institute, Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities. NIH Pub. No. 05–5282, Rockville

Watson M, Saraiya M, Benard V et al (2008) Burden of cervical cancer in the United States, 1998–2003. Cancer 113(10 Suppl):2855–2864

Hall HI, Uhler RJ, Coughlin SS, Miller DS (2002) Breast and cervical cancer screening among Appalachian women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 11:137–142

Schwartz KL, Crossley-May H, Vigneau FD, Brown K, Banerjee M (2003) Race, socioeconomic status and stage at diagnosis for five common malignancies. Cancer Causes Control 14:761–766

Patel DA, Barnholtz-Sloan JS, Patel MK, Malone JM Jr, Chuba PJ, Schwartz K (2005) A population-based study of racial and ethnic differences in survival among women with invasive cervical cancer: analysis of Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results data. Gynecol Oncol 97:550–558

Datta GD, Colditz GA, Kawachi I, Subramanian SV, Palmer JR, Rosenberg L (2006) Individual-, neighborhood-and state-level socioeconomic predictors of cervical carcinoma screening among US black women: a multilevel analysis. Cancer 106:664–669

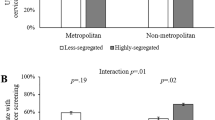

Coughlin SS, King J, Richards TB, Ekwueme DU (2006) Cervical cancer screening among women in metropolitan areas of the United States by individual-level and area-based measures of socioeconomic status, 2000 to 2002. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 15:2154–2159

Benard VB, Johnson CJ, Thompson TD et al (2008) Examining the association between socioeconomic status and potential human papillomavirus-associated cancers. Cancer 113(10 Suppl):2910–2918

Negoita S, Harrison JN, Qiao B, Ekwueme DU, Flowers LC, Kahn AR (2008) Distribution of treatment for human papillomavirus-associated gynecologic carcinomas before prophylactic vaccine. Cancer 113(10 Suppl):2926–2935

Hopenhayn C, King JB, Christian A, Huang B, Christian WJ (2008) Variability of cervical cancer rates across 5 Appalachian states, 1998–2003. Cancer 113(10 Suppl):2974–2980

Coughlin SS, Leadbetter S, Richards T, Sabatino SA (2008) Contextual analysis of breast and cervical cancer screening and factors associated with health care access among United States women, 2002. Soc Sci Med 66:260–275

Brookfield KF, Cheung MC, Lucci J, Fleming LE, Koniaris LG (2009) Disparities in survival among women with invasive cervical cancer: a problem of access to care. Cancer 115:166–178

Pruitt SL, Shim MJ, Mullen PD, Vernon SW, Amick BC 3rd (2009) Association of area socioeconomic status and breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer screening: a systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 18:2579–2599

Tan W, Stehman FB, Carter RL (2009) Mortality rates due to gynecologic cancers in New York state by demographic factors and proximity to a gynecologic oncology group member treatment center: 1979–2001. Gynecol Oncol 114:346–352

Hao Y, Ward EM, Jemal A, Pickle LW, Thun MJ (2006) US congressional district cancer death rates. Int J Health Geogr Jun 23:5–28

Krieger N (2005) Defining and investigating social disparities in cancer: critical issues. Cancer Causes Control 16:5–14

Newmann SJ, Garner EO (2005) Social inequities along the cervical cancer continuum: a structured review. Cancer Causes Control 16:63–70

Bosch FX, Lorincz A, Muñoz N, Meijer CJ, Shah KV (2002) The causal relation between human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. J Clin Pathol 55:244–265

Dillner J, Lehtinen M, Bjorge T et al (1997) Prospective seroepidemiologic study of human papillomavirus infection as a risk factor for invasive cervical cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 89:1293–1299

Koskela P, Anttila T, Bjorge T et al (2000) Chlamydia trachomatis infection as a risk factor for invasive cervical cancer. Int J Cancer 85:35–39

Anttila T, Saikku P, Koskela P et al (2001) Serotypes of Chlamydia trachomatis and risk for development of cervical squamous cell carcinoma. JAMA 285:47–51

Smith JS, Munoz N, Herrero R et al (2002) Evidence for Chlamydia trachomatis as a human papillomavirus cofactor in the etiology of invasive cervical cancer in Brazil and the Philippines. J Infect Dis 185:324–331

Wallin KL, Wiklund F, Luostarinen T et al (2002) A population-based prospective study of Chlamydia trachomatis infection and cervical carcinoma. Int J Cancer 101:371–374

Smith JS, Bosetti C, Munoz N et al (2004) Chlamydia trachomatis and invasive cervical cancer: a pooled analysis of the IARC multicentric case-control study. Int J Cancer 111:431–439

Madeleine MM, Anttila T, Schwartz SM et al (2007) Risk of cervical cancer associated with Chlamydia trachomatis antibodies by histology, HPV type and HPV cofactors. Int J Cancer 120:650–655

Chen J, Roth RE, Naito AT, Lengerich EJ, Maceachren AM (2008) Geovisual analytics to enhance spatial scan statistic interpretation: an analysis of US cervical cancer mortality. Int J Health Geogr 7:57

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2009) Sexually transmitted disease surveillance, 2008. Atlanta, Georgia: US Department of Health and Human Services. http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats08/surv2008-Complete.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2001) Tracking the hidden epidemics: trends in the United States 2000. Atlanta, Georgia: US Department of Health and Human Services. http://www.cdc.gov/std/Trends2000/Trends2000.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2001) Sexually transmitted disease surveillance, 2000. Atlanta, Georgia: US Department of Health and Human Services. http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats00/TOC2000.htm

Diggle PJ, Heagerty PJ, Liang KY, Zeger SL (2002) Analysis of longitudinal data, 2nd edn. Oxford University Press Inc, New York

Economic Research Service, US Department of Agriculture (2003) Rural-urban continuum codes (http://www.ers.usda.gov/Data/RuralUrbanContinuumCodes/2003/)

Krieger N, Rowley DL, Herman AA, Avery B, Phillips MT (1993) Racism, sexism, and social class: implications for studies of health, disease, and well-being. Am J Prev Med 9:82–122

Williams DR, Collins C (2001) Racial residential segregation: a fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Rep 116:404–416

Cates JR, Brewer NT, Fazekas KI, Mitchell CE, Smith JS (2009) Racial differences in HPV knowledge, HPV vaccine acceptability, and related beliefs among rural, southern women. J Rural Health 25:93–97

US Census Bureau, Census 2000 (2004) Accuracy and coverage evaluation of census 2000: design and methodology. US Department of Commerce. (http://www.census.gov/prod/2004pubs/dssd03-dm.pdf)

Brewster KL (1994) Race differences in sexual activity among adolescents women: the role of neighborhood characteristics. Am Sociol Rev 59:408–424

Laumann EO, Youm Y (1999) Racial/ethnic group differences in the prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases in the United States: a network explanation. Sex Transm Dis 26:250–261

Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ (2005) Social context, sexual networks, and racial disparities in rates of sexually transmitted infections. J Infect Dis 191(Suppl 1):S115–S122

Syrjanen K, Mantyjarvi R, Vayrynen M et al (1986) Coexistent chlamydial infections related to natural history of human papillomavirus lesions in uterine cervix. Genitourin Med 62:345–351

Jha PK, Beral V, Peto J et al (1993) Antibodies to human papillomavirus and to other genital infectious agents and invasive cervical cancer risk. Lancet 341:1116–1118

Paavonen J, Lehtinen M (1999) Interactions between human papillomavirus and other sexually transmitted agents in the etiology of cervical cancer. Curr Opin Infect Dis 12:67–71

Fischer N (2002) Chlamydia trachomatis infection in cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and invasive carcinoma. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 23:247–250

Tamim H, Finan RR, Sharida HE, Rashid M, Almawi WY (2002) Cervicovaginal coinfections with human papillomavirus and Chlamydia trachomatis. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 43:277–281

Giuliano AR, Papenfuss M, De Galaz EM et al (2004) Risk factors for squamous intraepithelial lesions (SIL) of the cervix among women residing at the US-Mexico border. Int J Cancer 109:112–118

Samoff E, Koumans EH, Markowitz LE et al (2005) Association of Chlamydia trachomatis with persistence of high-risk types of human papillomavirus in a cohort of female adolescents. Am J Epidemiol 162:668–675

Silins I, Ryd W, Strand A et al (2005) Chlamydia trachomatis infection and persistence of human papillomavirus. Int J Cancer 116:110–115

Dunne EF, Unger ER, Sternberg M et al (2007) Prevalence of HPV infection among females in the United States. JAMA 297:813–819

Dunne EF, Datta SD E, Markowitz L (2008) A review of prophylactic human papillomavirus vaccines: recommendations and monitoring in the US. Cancer 113(10 Suppl):2995–3003

Khan K, Curtis CR, Ekwueme DU et al (2008) Preventing cervical cancer: overviews of the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program and 2 US immunization programs. Cancer 113(10 Suppl):3004–3012

Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (2009) Recommended adult immunization schedule: United States, 2009. Ann Intern Med 150:40–44

Chang Y, Brewer NT, Rinas AC, Schmitt K, Smith JS (2009) Evaluating the impact of human papillomavirus vaccines. Vaccine 27:4355–4362

Tiro JA, Saraiya M, Jain N et al (2008) Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer behavioral surveillance in the US. Cancer 113(10 Suppl):3013–3030

Shepherd J, Peersman G, Weston R, Napuli I (2000) Cervical cancer and sexual lifestyle: a systematic review of health education interventions targeted at women. Health Educ Res 15:681–694

Zenilman JM (2001) Chlamydia and cervical cancer: a real association? JAMA 285:81–83

Kerner JF, Andrews H, Zauber A, Struening E (1988) Geographically-based cancer control: methods for targeting and evaluating the impact of screening interventions on defined populations. J Clin Epidemiol 41:543–553

Hall HI, Rogers JD, Weir HK, Miller DS, Uhler RJ (2000) Breast and cervical carcinoma mortality among women in the Appalachian region of the US, 1976–1996. Cancer 89:1593–1602

Lengerich EJ, Wyatt SW, Rubio A et al (2004) The Appalachia Cancer Network: cancer control research among a rural, medically underserved population. J Rural Health 20:181–187

Lengerich EJ, Tucker TC, Powell RK et al (2005) Cancer incidence in Kentucky, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia: disparities in Appalachia. J Rural Health 21:39–47

Kluhsman BC, Bencivenga M, Ward AJ, Lehman E, Lengerich EJ (2006) Initiatives of 11 rural Appalachian cancer coalitions in Pennsylvania and New York. Prev Chronic Dis 3:A122

Oakes JM (2004) The (mis)estimation of neighborhood effects: causal inference for a practicable social epidemiology. Soc Sci Med 58:1929–1952

Preventive Services Task Force US (2007) Screening for chlamydial infection: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 147:128–133

St Lawrence JS, Montano DE, Kasprzyk D, Phillips WR, Armstrong K, Leichliter JS (2002) STD screening, testing, case reporting, and clinical and partner notification practices: a national survey of US physicians. Am J Public Health 92:1784–1788

Pickle LW, Su Y (2002) Within-state geographic patterns of health insurance coverage and health risk factors in the United States. Am J Prev Med 22:75–83

Moore DA, Carpenter TE (1999) Spatial analytical methods and geographic information systems: use in health research and epidemiology. Epidemiol Rev 21:143–161

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Du, P., Lemkin, A., Kluhsman, B. et al. The roles of social domains, behavioral risk, health care resources, and chlamydia in spatial clusters of US cervical cancer mortality: not all the clusters are the same. Cancer Causes Control 21, 1669–1683 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-010-9596-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-010-9596-4