Abstract

Objective

This study examines new socio-ecological variables reflecting community context as predictors of mammography use.

Methods

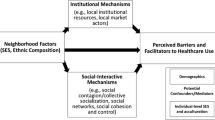

The conceptual model is a hybrid of traditional health-behavioral and socio-ecological constructs with an emphasis on spatial interaction among women and their environments, differentiating between several levels of influence for community context. Multilevel probability models of mammography use are estimated. The study sample includes 70,129 women with traditional Medicare fee-for-service coverage for inpatient and outpatient services, drawn from the SEER–Medicare linked data. The study population lives in heterogeneous California, where mammography facilities are dense but utilization rates are low.

Results

Several contextual effects have large significant impacts on the probability of mammography use. Women living in areas with higher proportions of elderly in poverty are 33% less likely to use mammography. However, dually eligible women living in these poor areas are 2% more likely to use mammography than those without extra assistance living in these areas. Living in areas with higher commuter intensity, higher violent crime rates, greater land use mix (urbanicity), or more segregated Hispanic communities exhibit −14%, −1%, −6%, and −3% (lower) probability of use, respectively. Women living in segregated American Indian communities or in communities where more elderly women live alone exhibit 16% and 12% (higher) probability of use, respectively. Minority women living in more segregated communities by their minority are more likely to use mammography, suggesting social support, but this is significant for Native Americans only. Women with disability as their original reason for entitlement are found 40% more likely to use mammography when they reside in communities with high commuter intensity, suggesting greater ease of transportation for them in these environments.

Conclusions

Socio-ecological variables reflecting community context are important predictors of mammography use in insured elderly populations, often with larger magnitudes of effect than personal characteristics such as race or ethnicity (−3% to −7%), age (−2%), recent address change (−7%), disability (−5%) or dual eligibility status (−1%). Better understanding of community factors can enhance cancer control efforts.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO) (2002) Mammography: capacity generally exists to deliver services. Report to the Chairman, special committee on aging, U.S. Senate. Publication # GAO-02-532, April 2002

Haas JS, Phillips KA, Sonneborn D, McCulloch CE, Liang SY (2002) Effect of managed care insurance on the use of preventive care for specific ethnic groups in the United States. Med Care 40(9):743–751. doi:10.1097/00005650-200209000-00004

Mainous AG III, Hueston WJ, Love MM, Griffith CH III (1999) Access to care for the uninsured: is access to a physician enough? Am J Public Health 89(6):910–912. doi:10.2105/AJPH.89.6.910

Qureshi M, Thacker HL, Litaker DG, Kippes C (2009) Differences in breast cancer screening rates: an issue of ethnicity or socioeconomics? J Womens Health Gend Based Med 9(9):1025–1031. doi:10.1089/15246090050200060

Sambamoorthi U, McAlpine DD (2003) Racial, ethnic, socioeconomic, and access disparities in the use of preventive services among women. Prev Med 37(5):475–484. doi:10.1016/S0091-7435(03)00172-5

Valdini A, Cargill LC (1997) Access and barriers to mammography in New England community health centers. J Fam Pract 45(3):243–249

Adams EK, Florence CS, Thorpe KE, Becker ER, Joski PJ (2003) Preventive care: female cancer screening, 1996–2000. Am J Prev Med 25(4):301–307. doi:10.1016/S0749-3797(03)00216-2

O’Malley MS, Earp JA, Hawley ST, Schell MJ, Mathews HF, Mitchell J (2001) The association of race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and physician recommendation for mammography: who gets the message about breast cancer screening? Am J Public Health 91(1):49–54

McWilliams JM, Zaslavsky AM, Meara E, Ayanian JZ (2003) Impact of Medicare coverage on basic clinical services for previously uninsured adults. JAMA 290(6):757–764. doi:10.1001/jama.290.6.757

Coughlin SS, Uhler RJ (2002) Breast and cervical cancer screening practices among Hispanic women in the United States and Puerto Rico, 1998–1999. Prev Med 34(2):242–251. doi:10.1006/pmed.2001.0984

Garbers S, Jessop DJ, Foti H, Uribelarrea M, Chiasson MA (2003) Barriers to breast cancer screening for low-income Mexican and Dominican women in New York City. J Urban Health 80(1):81–91

Klassen AC, Smith AL, Meissner HI, Zabora J, Curbow B, Mandelblatt J (2002) If we gave away mammograms, who would get them? A neighborhood evaluation of a no-cost breast cancer screening program. Prev Med 34(1):13–21. doi:10.1006/pmed.2001.0956

Mandelblatt JS, Gold K, O’Malley AS, Taylor K, Cagney K, Hopkins JS, Kerner J (1999) Breast and cervix cancer screening among multiethnic women: role of age, health, and source of care. Prev Med 28(4):418–425. doi:10.1006/pmed.1998.0446

Wu ZH, Black SA, Markides KS (2001) Prevalence and associated factors of cancer screening: why are so many older Mexican American women never screened? Prev Med 33(4):268–273. doi:10.1006/pmed.2001.0880

Kelaher M, Stellman JM (2000) The impact of Medicare funding on the use of mammography among older women: implications for improving access to screening. Prev Med 31(6):658–664. doi:10.1006/pmed.2000.0759

Lauver DR, Settersten L, Kane JH, Henriques JB (2003) Tailored messages, external barriers, and women’s utilization of professional breast cancer screening over time. Cancer 97(11):2724–2735. doi:10.1002/cncr.11397

Young RF, Waller JB Jr, Smitherman H (2002) A breast cancer education and on-site screening intervention for unscreened African American women. J Cancer Educ 17(4):231–236

Risendal B, Roe D, DeZapien J, Papenfuss M, Giuliano A (1999) Influence of health care, cost, and culture on breast cancer screening: issues facing urban American Indian women. Prev Med 29(6 Pt 1):501–509. doi:10.1006/pmed.1999.0564

Bobo JK, Dean D, Stovall C, Mendez M, Caplan L (1999) Factors that may discourage annual mammography among low-income women with access to free mammograms: a study using multi-ethnic, multiracial focus groups. Psychol Rep 85(2):405–416. doi:10.2466/PR0.85.6.405-416

Borrayo EA, Jenkins SR (2003) Feeling frugal: socioeconomic status, acculturation, and cultural health beliefs among women of Mexican descent. Cult Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol 9(2):197–206. doi:10.1037/1099-9809.9.2.197

Pearlman DN, Rakowski W, Ehrich B, Clark MA (1996) Breast cancer screening practices among black, Hispanic, and white women: reassessing differences. Am J Prev Med 12(5):327–337

Roetzheim RG, Chirikos TN (2002) Breast cancer detection and outcomes in a disability beneficiary population. J Health Care Poor Underserved 13(4):461–476. doi:10.1177/104920802762475111 Nov

Riley GF, Potosky AL, Klabunde CN, Warren JL, Ballard-Barbash R (1999) Stage at diagnosis and treatment patterns among older women with breast cancer: an HMO and fee-for-service comparison. JAMA 281(8):720–726. doi:10.1001/jama.281.8.720

Baker LC (2003) Managed care spillover effects. Annu Rev Public Health 24:435–456 Epub 06 Nov 2001

Riley GF, Potosky AL, Lubitz JD, Brown ML (1994) Stage of cancer at diagnosis for Medicare HMO and fee-for-service enrollees. Am J Public Health 84(10):1598–1604. doi:10.2105/AJPH.84.10.1598 Oct

Baker LC, Brown ML (1999) Managed care, consolidation among health care providers, and health care: evidence from mammography. Rand J Econ 30(2):351–374. doi:10.2307/2556084

Maxwell AJ (2000) Relocation of a static breast screening unit: a study of factors affecting attendance. J Med Screen 7(2):114–115. doi:10.1136/jms.7.2.114

Hyndman JC, Holman CD, Dawes VP (2000) Effect of distance and social disadvantage on the response to invitations to attend mammography screening. J Med Screen 7(3):141–145. doi:10.1136/jms.7.3.141

Engelman KK, Hawley DB, Gazaway R, Mosier MC, Ahluwalia JS, Ellerbeck EF (2002) Impact of geographic barriers on the utilization of mammograms by older rural women. J Am Geriatr Soc 0(1):62–68. doi:10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50009.x

Bronfenbrenner U (1979) The ecology of human development experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Sallis JF, Bauman A, Pratt M (1998) Environmental and policy interventions to promote physical activity. Am J Prev Med 15:379–397. doi:10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00076-2

Sallis JF, Owen N (1999) Physical activity and behavioral medicine. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA

Sallis JF, Owen N, Frank LD (2000) Behavioral epidemiology: a systematic framework to classify phases of research on health promotion and disease prevention. Ann Behav Med 22(4):294–298. doi:10.1007/BF02895665

Baranowski T, Anderson C, Carmack C (1998) Mediating variable framework in physical activity interventions: how are we doing? How might we do better? Am J Prev Med 15:266–297. doi:10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00080-4

Smedley BD, Syme SL (eds) (2000) Promoting health: strategies from social and behavioral research. National Academies Press/Institute of Medicine, Washington, DC

Wakefield J, Salway R (2001) A statistical framework for ecological and aggregate studies. J R Stat Soc Ser A 164:119–137

Schmid T, Pratt M, Witmer L (2006) A framework for physical activity policy research. J Phys Act Health 3(Suppl 1):S20–S29

Schulz AJ, Kannan S, Dvonch JT, Israel BA, Allen A III, James SA, House JS, Lepkowski J (2005) Social and physical environments and disparities in risk for cardiovascular disease: the healthy environments partnership conceptual model. Environ Health Perspect 113(12):1817–1825

Williams DR, Collins C (2001) Racial residential segregation: a fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Rep 116(5):404–416

Palloni A, Arias E (2004) Paradox lost: explaining the Hispanic adult mortality advantage. Demography 41(3):385–415. doi:10.1353/dem.2004.0024

Mobley LR, Root E, Finkelstein E, Khavjou O, Will J (2006) Relationships between the built environment and other contextual factors, obesity, and cardiac risk. Am J Prev Med 30(4):327–332. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2005.12.001

Warren JL, Klabunde CN, Schrag D, Bach PB, Riley GF (2002) Overview of the SEER Medicare data: content, research applications, and generalizability to the United States elderly population. Med Care 40:IV-3–IV-18

Mobley LR, Kuo TM, Andrews L (2008) How sensitive are multilevel regression findings to defined area of context?: a case study of mammography use in California. Med Care Res Rev 65(3):315–337

Aday LA, Andersen R (1974) A framework for the study of access to medical care. Health Serv Res 9(3):208–220

Goodman DC, Mick SS, Bott D, Stukel T, Chang C, Marth N, Poage J, Carretta HJ (2003) Primary care service areas: a new tool for the evaluation of primary care services. Health Serv Res 38(1):287–310. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.00116

Massey DS, Denton NA (1988) The dimensions of residential segregation. Soc Forces 67(2):281–315. doi:10.2307/2579183

Schulz AJ, Williams DR, Israel BA, Lempert LB (2002) Racial and spatial relations as fundamental determinants of health in Detroit. Milbank Q 80(4):677–707. doi:10.1111/1468-0009.00028

Mobley LR, Root ED, Anselin L, Lozano-Gracia, N, Koschinsky J. (2006) Spatial analysis of elderly access to primary care services. Int J Health Geogr 5 Epub 15 May 2006. http://www.ij-healthgeographics.com/content/5/1/19. doi:10.1186/1476-072X-5-19

Mick S, Lee S, Wodchis W (2000) Variations in geographical distribution of foreign and domestically trained physicians in the United States: ‘safety nets’ or ‘surplus exacerbation’? Soc Sci Med 50:185–202. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00183-5

CAH/FLEX National Tracking Project, Findings from the field (2003) The role of international medical graduates in America’s small rural “critical access” hospitals. June 20, 2003:3(1)

Loukaitou-Sideris A, Eck J (2007) Crime prevention and active living. Am J Health Promot 21(Suppl 4):380–389 March/April

Keane C (1998) Evaluating the influence of fear of crime as an environmental mobility restrictor on women’s routine activities. Environ Behav 30(1):60–74. doi:10.1177/0013916598301003

Meyer E, Post L (2006) Alone at night: a feminist ecological model of community violence. Fem Criminol 1:207–227. doi:10.1177/1557085106289919

Ai C, Norton E (2003) Interaction terms in logit and probit models. Econ Lett 80:123–129. doi:10.1016/S0165-1765(03)00032-6

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a National Cancer Institute grant (5 R21 CA117869-02), “Spatial Impact Factors and Mammography Use.” The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of RTI International, the National Cancer Institute, or the National Institutes of Health. Databases developed under this funding with contextual variables defined at ZCTA, PCSA, MSSA (California) and county levels are available to interested researchers, who may send a self-addressed and stamped envelope with media (two 4.6 GB DVDs) to Dr. Mobley.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mobley, L.R., Kuo, TM., Clayton, L.J. et al. Mammography facilities are accessible, so why is utilization so low?. Cancer Causes Control 20, 1017–1028 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-009-9295-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-009-9295-1