Abstract

Our paper contributes to emerging management research on the effects of societal inequality. It aims to study the relationship between societal-level inequality and perceived unequal HR practices within organizations based on relationships which we term “relation-based inequality” (RBI). We further examine the moderating effect of country corruption on the RBI-employee commitment link. Thus, whereas previous research has looked at single countries, there is still much to know about societal effects of inequality and corruption on employee perceptions and attitudes at work across countries. By surveying 691employees from five countries and using country-level indicators we take a first step in this direction, and establish that inequality (income, health and education) is linked to higher levels of relation-based HR practices. We also show that the effect of RBI is different for continuance, affective and normative commitment, and contingent on country corruption levels.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The second decade of the twenty-first century has been plagued by social unrest arising from societal inequality. The Occupy movement protests brought the issue forcibly to the world’s attention in 2011, and the subsequent gender-based #MeToo movement and anti-racist #BlackLivesMatter movements soon followed (Younge, 2019). In the first six months of 2020, the tragic consequences of inequality became plain for all to see in the disproportionate fatality rates of the underprivileged during the COVID-19 pandemic (van Dorn et al., 2020).

While research is emerging into how societal inequality manifests within organizations (Beal & Astakhova, 2017), investigation into the topic by management scholars is still in its infancy (Bapuji et al., 2020a). Our paper therefore focuses on one aspect of inequality in organizations: the unequal treatment of employees resulting from human resource (HR) practices based on relationships rather than merit. We term this phenomenon “relation-based inequality” (RBI) and study individual employee perceptions of whether decisions in their organization in areas such as recruitment, appraisal and promotion tend to favor employees who have a social tie (family, friendship or favored colleague) with the decision-maker. Research has tended to focus on specific relationships such as nepotism in family-owned businesses (e.g. Spranger et al., 2012), but our investigation addresses the perceived preferential behavior seen in nepotism, favoritism and cronyism, irrespective of type of social tie. We examine this phenomenon in relation to societal contexts, specifically societal inequality and country-level corruption, and investigate its relationship with employee commitment.

Understanding how societal inequality and corruption play out in management practices and employee outcomes will enable organizations to take a proactive stance in adapting their HR activities in contexts where such action is sorely needed. Addressing inequality in organizations is a major challenge in business ethics (Beal & Astakhova, 2017), thus we examine this issue by analyzing employee perceptions of RBI in their organizations across five countries with differing degrees of inequality and corruption, namely South Africa, Russia, China, the United States and Germany. Drawing on institutional theory (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983), we suggest that organizational HR practices will reflect inequalities in the society in which the firm operates, and that employees will perceive these inequalities. We base our reasoning on research showing that societal inequality in income or access to health and education means that individuals carry these inequalities into their working life (Bapuji, 2015). Thus, access to health and education is linked to a person’s technical and social skills and abilities, which strongly predict the likelihood of finding a good job and subsequent career success (Crawford et al., 2016). Crucially, societal inequality also leads to inequality in access to the resources associated with social capital and relationship networks (Fukuyama, 2001; Portes, 1998), whose role in providing access to work and supporting career progress is vital (Seibert et al., 2001). Equally, corruption levels in the society in which the organization operates will shape how employees view and react to unequal treatment.

Our work offers four principal contributions to business ethics research into inequality and its effects on employee outcomes, responding to calls for deeper understanding of the link between societal inequality and individuals’ experiences at work (Bapuji et al., 2020a). First, we show that perceived unequal HR practices act as a mechanism through which societal-level inequality can be linked to individual employee commitment. In so doing, we bridge the gap between employees’ experience of inequality both within and outside an organization. Thus, we reveal a previously unestablished mechanism for linking societal health, income and educational inequality experienced by individuals, on the one hand, and access to the “right” social ties at work, on the other.

Second, we contribute to the conceptualization of a particular type of inequality in organizations that is based on social relationships. Previous work has examined this phenomenon from various perspectives, for instance, preferential treatment of employees through family ties (nepotism; e.g. Spranger et al., 2012), friendship or acquaintance within the organization (favoritism; e.g. Wang et al., 2018) or corrupt ties outside the company (cronyism; e.g. Khatri et al., 2006). Providing a broad definition and measurement tool for perceptions of unequal treatment in HR practices allows scholars to move away from a siloed approach to inequality and enables them to make comparisons across different organizational types, social ties and cultures.

Third, we contribute to the research on the phenomena of nepotism, cronyism and favoritism at work and their link to employee outcomes by incorporating the role of societal-level corruption. While the literature has shown detrimental effects of such phenomena (Hudson et al., 2019; Khatri & Tsang, 2003), they may be contingent on societal factors such as political systems or cultural values (Pearce et al., 2000; Smith et al., 2012). However, no studies have compared employees’ perceptions of their own organizational practices across multiple countries. By examining five nations, we contribute to this research stream by demonstrating that country corruption plays a significant role in shaping the effects of RBI on employee outcomes.

Finally, we developed an inclusive instrument to measure RBI in organizations. This index encompasses a wide range of HR practices appropriate for different types of organizations and social ties. Existing measures are limited to distinct organizational types and particular HR practices.

Theoretical Background

Relation-Based Inequality in Organizations

RBI, the unequal treatment of employees based on social ties rather than merit, has been the object of research under various nomenclatures. Some research examines inequality in the workplace in terms of ingroup/outgroup bias (Heneman et al., 1989; Wang et al., 2018), where one favors one’s own group over outsiders. Other streams investigate workplace effects of stereotyping (Li et al., 2017; Posthuma & Campion, 2009) or discrimination by race, gender and age (Goldman et al., 2006). Our approach differs from ingroup/outgroup bias and race/gender discrimination in that it concerns individual social ties with family, friends or colleagues rather than the generalized attitude involved in ingroup/outgroup bias. Specifically, our definition of RBI encompasses personnel decisions in the working life of an employee, such as recruitment, selection, promotion and rewards (named particularism by Hudson et al., 2019). It opposes the merit-based perspective, where employees receive recognition and rewards for standardized, objectively measured performance beyond ordinary expected performance. We measure this construct through the prism of employee assessments of these practices in their organization (Appendix), and hereinafter we use “RBI” to refer to employee perceptions of relation-based inequality at work.

Previous country-level research has established that RBI in the form of nepotism, favoritism and cronyism occurs in organizations worldwide (Burhan et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2013; Sidani & Thornberry, 2013; Smith et al., 2012; Wated & Sanchez, 2015), and popular media also abounds with stories of nepotism and cronyism in nations from around the world (e.g. Butler, 2020; Chalabi, 2017). Despite the amount of attention this subject has received, only a few studies have compared such practices between different nations or examined their effects. For example, in a conceptual paper, Khatri et al. (2006) analyze cultural differences in cronyism based on cultural values and types of crony behaviors at an institutional level. Smith et al. (2012) asked managers in four countries to rate how typical certain forms of social influence such as “guanxi, wasta, jeitinho, svyazi and pulling strings” (p. 2012) were (in a business scenario) and linked these ratings to cultural dimensions. Pearce et al. (2000) compared employee perceptions of favoritism in the “modernist” US and “neo-traditional” Hungary. However, to our knowledge, there is no empirically based study of working employees that compares perceived unequal HR practices in organizations across countries and relates them to societal inequality and corruption levels.

Societal Inequality and Country-Level Corruption

Discussions around the definitions of inequality in the management literature are often vague regarding the level of analysis, be it state, group or individual (see Bapuji et al., 2020a, for a review). In the context of our study, in which we differentiate societal-level inequality from unequal practices within organizations, it is worth reflecting on the conceptualization and measurement of inequality. At the societal level, Piketty (2015) distinguishes long-standing wealth inequality from income inequality, whereas Cobb (2016) treats societal and organizational income inequality as the same construct, defined as “the distribution of income across participants in a collective, be it an organization, a region, or a country” (p. 326). Bapuji (2015) emphasizes inequality in the broader sense as an unequal dispersion of resources and labor rewards, and Hayes et al. (2018) refer to asymmetries in group power at any level of analysis, a definition leaning towards the concept of RBI we examine within organizations in this study.

For the purposes of our research, we use a concept of societal-level inequality closer to that defined by Bapuji et al. (2020a) than to income inequality (Cobb, 2016) and dissimilar to the notion of inequality through power asymmetry (Hayes et al., 2018). Our definition and measurement of societal inequality originates in the United Nations human development approach based on inequalities in health, education and income, encompassing both economic and social factors (United Nations Development Programme [UNDP], 2020a).

Societal inequality has profound effects on individuals’ access to a raft of resources such as networks enabling access to jobs, admission to certain schools and access to health care (Bapuji, 2015). Those who benefit from societal inequality gain privilege that can shape characteristics appropriate to job access, such as skills, ability, behavior and even appearance, which compound the differences between the privileged and underprivileged (Corak, 2013; Hudson & Claasen, 2017).

Research has shown that societal inequality is linked to corruption (You & Khagram, 2005), where inequality tends to support social tolerance of corruption, allowing it to grow. In turn, corruption bolsters inequality by granting the wealthy greater access to resources, creating a vicious circle. In other words, societal inequality and corruption go hand in hand, and both play a role in the institutional landscape in which an organization exists. Subsequently, institutional theory suggests that organizations will reflect these issues in their actions (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983). Therefore, to examine RBI in organizations, we first provide an overview of the institutional and societal environments of the countries under study. Appendix table 4 provides a summary table.

South Africa

South Africa’s institutional environment is tumultuous and multifaceted. The after-effects of formerly practiced apartheid policies and laws (1948–1994) and exclusion, combined with current unethical political and economic practices, have resulted in a racially tense, corrupt and unequal society. Corruption is high and seen as pervasive and systemic (Merchant, 2016). Political patronage, favoritism and nepotism are rampant (Pitcher, 2012). The well-studied link between destructive rent-seeking, poor economic performance and extremely high levels of inequality is clearly visible (Bhorat et al., 2014). South Africa is one of the most unequal societies in the world, and women are particularly disadvantaged (Khuzwayo, 2016). According to the latest figures from the World Inequality Database (2017), the top 10% of South African earners take home almost 65% of all income in the country. Relation-based societal values are rooted in Ubuntu philosophy and paternalism and include a moral responsibility for the community and caring for one’s family (Metz, 2009). The most common RBI organizational practices are favoritism, nepotism and cadre-employment (Dzansi et al., 2016; Tshishonga, 2014).

Russia

Institutionally, Russia is very weak, as it is plagued by high corruption levels and moderately high inequality compared with other countries (Guriev & Zhuravskaya, 2010). It is an environment of “institutional chaos,” which leads to significant uncertainty for society and Russian firms in particular (Becker, 2019). Societal perception is that the government is ineffective and only serving its own interests (Ledeneva, 2013). Economic growth since 2000 has slightly reduced the income gap between rich and poor, but this gap is still exacerbated by factors such as corruption and low taxes for the rich (Russell, 2018). Ingrained relation-based societal values are collectivism (Hitt et al., 2004) and paternalism (Hardwick, 2014). Personal relationships are important (Scott, 2008) and RBI-based practices such as blat (the use of connections and favors; Ledeneva, 2013; Puffer & McCarthy, 2003), favoritism and nepotism (Safina, 2015) are prevalent. These practices still take place at the organizational level, although in some cases a more merit-based approach has emerged (Safina, 2015). Despite improvement in the last 25 years, gender inequality is still relatively high (Zakirova, 2014).

China

China’s institutional environment is predominantly influenced and shaped by its communist one-party state regime and its relatively new status as a major global economic power. However, China’s economic success did not automatically lead to less inequality and lower corruption levels. Despite the anti-corruption drive, which began in 2012 (Horsely, 2019), the level of corruption in China is far higher than that of most high-income economies (World Bank, 2017). One of the problems is the relative lack of the rule of law, which leads to widespread government corruption, financial speculation, misallocation of investment funds and favoritism by government officials (Zúñiga, 2018). In many cases, government “connections,” not market forces, are the main determinant of firms’ success in China (Horsley, 2019). RBI in the form of guanxi in China is an omnipresent practice in all spheres of life, including the workplace (Bedford, 2011; Chen & Godkin, 2001). Guanxi defines relationships that emphasize expected reciprocal social practices within a person’s network of social connections (Bedford, 2011). The Chinese management style stems from the Confucian values of paternalism, the importance of family, filial piety and loyalty (Bedford, 2011; Chen & Godkin, 2001). Gender inequality remains a problem, and China has not improved its performance in the last five years compared with other countries (UNDP, 2020b).

Germany

Germany is the fourth-largest economy in the world and the largest European economy (OECD, 2015). The country shows falling unemployment, increased exports, comparatively stable growth rates and great wealth (OECD, 2015). Germany has scored consistently low on corruption levels even though much more should be done to enforce sanctions against non-compliant companies bribing overseas, and better separation between business and domestic politics is needed (OECD, 2018). Some link the increase of nationalism in Germany to an upsurge in inequality, suggesting that many Germans have been left behind despite the country’s economic success (Schulz, 2019). The gap between rich and poor regions keeps widening, and though several cities and districts are booming, other regions are lagging (Felbermayr et al., 2014). Recent legislation is narrowing the gender gap in pay and political participation, but women still earn approximately 20% less than men (Rühlemann et al., 2016). Germany has relatively strong employment laws, and most German workers possess technical or academic qualifications. Most employees are also represented by works councils and/or a union, providing relatively high levels of empowerment and ensuring that workers are treated fairly and with dignity (OECD, 2012).

The United States

The US is an ethnically and racially diverse nation as a result of large-scale immigration from many countries over distinct historical periods (Thompson & Hickey, 2005). It is also a capitalist country dominated by giant companies (Khanna & Francis, 2016), relatively weakly regulated markets that exist in a globalized system of economic interactions and weak workers’ unions (Galbraith & Choi, 2020). So far, the US has been associated with relatively low levels of corruption (Transparency International, 2019), but there is an increasing level of inequality (UNDP, 2020b) and racial discrimination (Galbraith & Choi, 2020). Rising economic inequality is closely tied to the high concentration of capital asset ownership and structural transformation of the US economy over the last 50 years, especially the decline of unionized manufacturing (Galbraith & Choi, 2020). Income inequality has been on the rise for the past four decades and reached levels last seen during the great depression (Atkinson et al., 2011). The country dropped four points in the most recent corruption perceptions index. Some of the problems cited are “threats to its system of checks and balances” and “the ever-increasing influence of special interests in government” (Transparency International, 2019). US employment relations have long been marked by the distinction of non-unionism (Kochan et al., 1994) and weak unionism (White, 2002) stemming from the dominance of an individualistic ideology in the US business system. However, some argue that there has been a significant strengthening of employment regulation over the past half-century in the US, as embodied in statutes, administrative rulings, and court decisions (Estlund, 2010). Relation-based organizational practices such as nepotism (Stinson & Wingnall, 2014), favoritism (US Merit Systems Protection Board, 2013) and cronyism (Smith & Sutton, 2012) also occur despite a bewildering array of anti-nepotism laws or general ethical guidelines on disclosure, which vary from state to state (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2016). The movement for gender equality made great strides in the latter half of the twentieth century but has since stalled, and many gender related inequalities still exist (Garlow, 2018).

Hypothesis Development

Societal Inequality and Relation-Based Inequality in Organizations

Scholars have recently turned their attention to the nexus between societal-level inequality and organizational- and employee-level effects (Bapuji, 2015; Bapuji et al., 2020a, 2020b; Cobb, 2016). This body of work emphasizes the fact that social and economic inequality and inequalities within organizations have an interdependent relationship (e.g. Cobb, 2016) and has called for investigation into how socioeconomic inequality plays out in the workplace (Bapuji et al., 2020a). Institutional theory (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983) suggests that organizations reflect the social norms and values of the society in which they operate, and recent research has suggested that this is indeed so with regard to inequality both internal and external to an organization (Bapuji et al., 2020a; Bidwell et al., 2013). Bidwell et al. (2013) argue that societal emphasis on shareholder returns relative to rewards to other stakeholders has increased societal inequality and compounded the difficulties of disadvantaged groups within organizations. Organizations are thought to influence societal inequality through their active participation in shaping societal norms and processes (Beal & Astakhova, 2017; Cobb, 2016). Conversely, Bapuji (2015) suggests that income inequality affects organizational performance because it affects human development within the society from where the employees originate. He makes the case that societal inequality acts in two ways in organizations: First, by affecting the institutions in which organizations are embedded, and second, through direct effects on the employees themselves. A small but growing number of studies have found links between economic or social inequality on the one hand and employee attitudes and behaviors on the other. For instance, various employee outcomes such as ethical thinking (Chen, 2014), absenteeism (Andrews & Htun, 2018), bullying (Soylu & Sheehy-Skeffington, 2015), satisfaction (Wu & Lin, 2018) and health outcomes (Jiang & Probst, 2017) have been linked to socio-economic inequality (see Bapuji et al., 2020a, for a review).

Institutional theory and empirical research thus converge in agreeing that societal-level inequality is mirrored in attitudes and behavior in the workplace. When societal inequality is high, the difference in citizens’ access to education, health care and income opportunities creates privileged and disadvantaged groups whose societal status may determine how they are treated—for example, in the allocation of rewards or jobs (Bidwell et al., 2013). We thus suggest that organizations operating within societies with high levels of inequality are more likely to engage in unequal HR practices, and therefore employees are more likely to perceive such practices in the workplace. Our first hypothesis is therefore:

Hypothesis 1

Societal inequality is positively related to RBI in organizations.

Relation-Based Inequality, Country Corruption Level and Organizational Commitment

In countries with higher inequality, research has suggested that its detrimental effects on the personal lives of individuals can spill over into the workplace (Amis et al., 2020; Bapuji et al., 2020a) and reduce organizational commitment. For example, links have been observed between inequality, financial worries and workplace stress (Ragins et al., 2014) or fatigue (Andrews & Htun, 2018) leading to lower organizational commitment. Amis et al. (2020) point out that this creates a vicious circle, where inequality, for example in terms of gender and class (Rivera & Tilcsik, 2016) means that an employee possesses less time and energy to contribute to and participate in the life of their organization. Such individuals are then viewed by management as lacking commitment. That perception of low commitment then interferes with career advancement, reinforcing the initial societal disadvantage suffered by the employee.

Within organizations, some studies have found that particularism and cronyism, both encompassed within our definition of RBI, have a detrimental effect on employee organizational commitment (Hudson et al., 2019; Khatri & Tsang, 2003; Pearce et al., 2000). Previous research has suggested that this is so because, first, individuals who do not benefit from the favored treatment may perceive injustice and be less committed to the firm (Hudson et al., 2019). Alternatively, those who benefit from relation-based preferential treatment may feel higher commitment to the person allocating the resources than to the company as a whole (Khatri & Tsang, 2003).

However, because previous studies examined single countries, researchers were unable to investigate the role of societal-level factors in the relationship between RBI and employee outcomes. In particular, country-level corruption often goes hand in hand with individuals and organizational actors using social ties for personal benefit rather than following the rules and procedures set down by institutions (Hudson & Claasen, 2017; Khatri, 2016). Institutional and country-level corruption is known to influence organizational corruption (Ashforth et al., 2008). Therefore, if an individual lives and works in a corrupt environment, they are likely to absorb such norms, which in turn will influence the assessment and effects of the practices of their employer (Ashforth & Anand, 2003; You & Khagram, 2005). Consequently, country corruption is likely to play a significant role in determining the indirect effect of inequality through RBI on employees.

Further, because organizational commitment is a multidimensional construct, it is likely that country-level inequality, acting through the mediation of RBI, has distinct outcomes regarding the different types of commitment, whereas these have been treated as a single, general concept in previous studies (Khatri & Tsang, 2003; Pearce et al., 2000). Organizational commitment (Allen & Meyer, 1990) is the degree to which an individual wishes to remain in, and contribute to their organization. It can be grouped into three dimensions: continuance commitment, the employee’s assessment of the risks of leaving the firm; affective commitment, which concerns the employee’s emotional bond and engagement with the organization; and normative commitment, which relates to normative beliefs about whether one has a duty of loyalty to the company.

Continuance commitment (Allen & Meyer, 1990) relies on factors external to the firm, because it includes an assessment of the likelihood of obtaining work elsewhere as well as the costs or sacrifices associated with leaving one’s current job. The literature on continuance commitment has argued that part of the construct can be thought of as measuring perceived employment alternatives or lack of alternatives (Jaros & Culpepper, 2014). A meta-analysis of empirical studies on organizational commitment shows that continuance commitment is highly correlated with work alternatives and transferability of skills (Meyer et al., 2012), both related to factors external to the company.

Concerning work alternatives, if both one’s current organization and its socioeconomic context operate through the use of social relationships, as seen in the example of Russia (Puffer & McCarthy, 2011), an employee may stay at their job because they simply do not have the relationships necessary to move to a new position. In contrast, in a country such as Germany, where corruption is low, RBI is unlikely to relate to an employee’s continuance commitment, as they have opportunities available elsewhere if they are uncomfortable with relation-based internal HR processes. Using relationships in the job market is high in corrupt contexts across all sectors of business activity (Aßländer & Hudson, 2017). Consequently, in-company RBI may be more likely to go hand in hand with higher continuance commitment in broader contexts where corrupt relation-based decisions are rife. We therefore hypothesize:

Hypothesis 2

The positive indirect relationship between societal inequality and continuance commitment mediated by RBI is moderated by country corruption, such that RBI has a stronger positive relationship with continuance commitment in countries with high rather than low corruption.

The second dimension, affective commitment, is the degree to which “an individual identifies with, is involved in, and enjoys membership in the organization” (Allen & Meyer, 1990, p. 2). Affective commitment is related to RBI because it rests on strong feelings of identification with the organization. An employee who feels “left out” will perceive less identification with, involvement in and membership in an organization that excludes them from the rewards and resources offered to those who possess the right connections (Hudson et al., 2019). Those who are treated more favorably may be more committed to the person or small group doling out the favors than to the firm as a whole (Khatri & Tsang, 2003).

RBI in organizations has been shown to impact affective commitment in previous studies on nepotism, cronyism and favoritism (Hudson et al., 2019; Pearce et al., 2000). If an organization’s HR practices do not recognize and reward merit or performance and instead offer benefits based on social ties, this may result in lower affective commitment due to perceptions of unfair treatment (Meyer et al., 2012).

We suggest that the negative relationship between RBI and affective commitment is stronger in low-corruption contexts and weaker when corruption is high. Individuals internalize the social norms of the society in which they live and work (Cialdini & Goldstein, 2004), learning and absorbing what type of behavior is common in their society. When the norms that employees observe in their company differ from societal norms, individuals experience cognitive dissonance (Festinger, 1957) and are likely to experience reduced affective commitment because cognitive inconsistency is tightly bound to negative affective states (Festinger, 1957). Thus, in countries with low corruption, employees who encounter RBI in their firm are likely to feel that the use of relationships rather than merit-based practices to make HR decisions is unacceptable or abnormal. The gap between their socially learned expectations and the company’s HR practices will mean that RBI has a stronger negative relationship with affective commitment. In societies where corruption is high, employees are more likely to be accustomed to the use of relational ties for decisions in society, and thus dissonance is lower between societal corruption and internal practices. We therefore hypothesize:

Hypothesis 3

The negative indirect relationship between societal inequality and affective commitment mediated by RBI is moderated by country corruption, such that RBI has a stronger negative relationship with affective commitment in countries with low rather than high corruption.

Finally, normative commitment is a personal value, specific to each individual, that indicates whether they believe that remaining loyal to one’s company is right and good (Allen & Meyer, 1990) and that they owe something to the company (Meyer & Parfyonova, 2010). Generally speaking, we would not expect external factors to have a large effect on embedded personal values. However, positively perceived HR practices can influence normative commitment if employees internalize corporate norms of “lifelong” commitment to the firm (Meyer & Parfyonova, 2010). Moreover, because normative commitment includes a notion of reciprocity, fair or caring HR practices may lead an employee to stay committed because they feel they owe their employer loyalty in return. Conversely, this obligation would be forfeit if the company treated employees unfairly based on social relationships rather than merit. For example, Sally may prize loyalty to her employer in general terms, but on observing continual promotion of her colleagues due to their relationship with the manager while she is passed over despite good performance, she might conclude that her values of loyalty are simply misplaced. Thus, RBI will have a negative relationship with normative commitment.

If country-level corruption is high, an individual may internalize the societal norms of using social ties for benefit (Ashforth & Anand, 2003; Cialdini & Goldstein, 2004) in an exchange relationship. Therefore, RBI in one’s organization in a context of high country corruption is unlikely to trigger a feeling of dissonance (Festinger, 1957), and we would expect the negative relationship between RBI and normative commitment to be weakened. Conversely, in countries with low corruption, where employees have not absorbed the societal norms that unequal treatment is somehow acceptable, individuals will perceive a clash between their own norms and those of the organization engaging in RBI, and thus the negative link between RBI and normative commitment will be stronger. Our hypothesis is therefore:

Hypothesis 4

The negative indirect relationship between societal inequality and normative commitment mediated by RBI is moderated by country corruption, such that RBI has a stronger negative relationship with normative commitment in countries with low rather than high corruption.

Method

Procedure and Sample

We tested our hypotheses using an online survey with employees working for organizations in public and private sectors in five countries: South Africa (N = 124), Russia (N = 161), China (N = 109), the US (N = 158), and Germany (N = 139). We chose these countries based on a combination of their corruptionFootnote 1 (Transparency International, 2018) and societal inequality (Coefficient of Human Inequality, UN, 2018) indices. Thus, Germany has low corruption levels and low inequality; Russia has very high corruption and low inequality; South Africa has very high inequality and medium levels of corruption; and China and the US have medium levels of inequality and corruption, with China slightly higher on both counts (see Table 1). These countries were also chosen for their diversity in terms of their historical and political landscapes (see Appendix table 4), meaning that they are likely to differ in their attitudes and practices concerning inequality in the workplace and in society in general, generating adequate variability for any general patterns to become visible in the data.

We collected data with a professional service in each country. The survey first asked about participants’ perceptions of RBI in HR decisions and the acceptability of these practices, then our outcome variables and finally the control and demographic variables. All participants were assured that their responses would be kept strictly confidential, and no data was gathered that could identify the individual. Participants’ average age was 39.7 years (SD = 11.25) with average job tenure of 9.26 years (SD = 8.20), and 330 (47.8%) participants were female.

Measures

We created Chinese and Russian versions of all measures by using the services of an official translator. This first version of each survey was then reviewed by two colleagues, researchers in the management field whose native language was either Chinese or Russian. German participants indicated their ability to respond in English before answering the survey.

Societal Inequality

We used the Coefficient of Human Inequality developed by the UNDP (n.d.). It calculates societal inequality as the mean of the inequality indices in health, education, and income. In broad terms, a score of above 30 indicates very high inequality, and below 10 indicates low inequality.

RBI in HR Practices

Existing scales of inequality at work in the form of nepotism, favoritism and cronyism are limited to particular organizational types (e.g. family-owned; Spranger et al., 2012); measure behavior or perceptions across one particular type of social tie such as family, friend, or social or political acquaintances (e.g. family; Wated & Sanchez, 2015; cronies; Turhan, 2014) or pertain to particular HR practices (Spranger et al., 2012). We therefore developed a more exhaustive measure covering a wider range of HR practices applicable to various types of organizations and social ties, in line with our conceptualization of RBI. We followed the procedure outlined by Diamantopoulos and Winklhofer (2001) for index development. Our index measures perceptions of RBI in various HR practices, namely recruitment and selection, appraisal, promotion, compensation and rewards, tolerance to misbehavior, participation in decision making and access to resources. Appendix presents a summary of the index development procedure and items.

The final RBI index comprises the aforementioned eight categories of HR practices, with 29 items. Using a seven-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 7 (all the time), we asked, “To what extent do each of the following practices happen in your company?” An example item is “Promotion can be faster for family, friends or favored colleagues.”

Corruption

We used the corruption perceptions index (CPI) calculated by Transparency International (2018) based on the perceptions of corruption in a country’s public sector by experts and business executives. It comprises 13 surveys and assessments of corruption collected by a variety of institutions. The CPI measures transparency, from a low score of 10 for the country with the highest corruption level (i.e., Somalia) to a high 88 for the lowest corruption (i.e., Denmark). Thus, the lower the score, the higher the corruption. For ease of interpretation, with higher levels reflecting higher corruption, we carried out a linear transformation (1/x × 100). For example, Germany scores 80 in the original index and is thus 1.25 in the transformed scale.

Organizational Commitment

We used the scale developed by Allen and Meyer (1990), with 22 items anchored by 1 (strongly disagree) and 7 (strongly agree).

Continuance Commitment

We used seven items to measure continuance commitment. An example item is “It would be very hard for me to leave my organization right now, even if I wanted to” (α = 0.78).

Affective Commitment

We used eight items to measure affective commitment. An example item is “I would be very happy to spend the rest of my career with this organization” (α = 0.87).

Normative Commitment

We measured normative commitment with seven items. An example item is “I think that people these days move from company to company too often” (α = 0.72).

Control Variables

Previous studies on specific or general manifestations of inequality at work found that gender, organizational size, type of organization, use of social ties during the recruitment process and attitude toward RBI might influence people’s behaviors in organizations with RBI (e.g. discrimination, Goldman et al, 2006; particularism, Hudson et al., 2019). We thus controlled for each of these variables in all our models. We measured gender with a dummy variable (5 = female, − 5 = male). Organizational size was measured by the number of employees. To measure type of organization, we created a dummy variable for each type of organization (private family-owned business (FOB), private non-FOB, government-owned business, non-governmental organization and other) with 1 (type of organization) and 0 (all other types). We measured use of social ties with a single item: “I benefited from using other relationships outside the company when I was recruited.” Responses were anchored by 1 (not at all) and 5 (a great deal). Finally, we measured “attitudes toward RBI” with the same items for RBI, changing the instructions to “how acceptable are the following organizational practices to you?”.

Results

We first examined potential errors in our analyses attributable to common method variance (CMV). First, we ran Harman’s single-factor test (Harman, 1976). We calculated the amount of variance accounted for in a one-factor unrotated solution in an exploratory factor analysis, using the two main continuous variables in the model (i.e., RBI, attitude toward RBI), and the three types of organizational commitment (continuance, affective, and normative). The amount of variance explained by this one-factor model was 33%, which led us to conclude that CMV was not a serious problem, as most of the variance was not accounted for by the single factor (Podsakoff & Organ, 1986). Second, confirmatory factor analysis established discriminant validity among the self-report measures. We tested a model with the five independent factors—RBI, attitudes toward RBI, continuance, affective and normative commitment—against various other possible models where we collapsed scales to create one- to four-factor models on theoretical grounds. The five-factor model had the following fit statistics: χ2 = 8903.89, df = 3022, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.05, CFI = 0.90. Overall, these results show that the five-factor model provides a good model fit, superior to alternative models (comparing the five-factor model with collapsing the factors into a single factor, Δχ2 = 13,926.25, df = 10, p < 0.001). These analyses show discriminant validity for the measures. Third, our model included country-level variables from sources external to our sample, namely societal inequality and corruption. This provided predictors and dependent measures from different sources as suggested by Podsakoff et al. (2003) as a way of reducing common methods bias.

Analytic Strategy

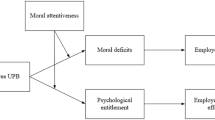

We used the PROCESS macro developed by Hayes (2017) to test our hypotheses. Specifically, we used Model 14, which allowed us to test our overall moderated mediation model. We entered societal inequality as the independent variable, RBI as mediator, corruption as moderator of the second path of our model and each type of organizational commitment as dependent variable. Organizational size, gender, type of organization, social tie and attitudes toward RBI were entered as controls. In all cases, we mean-centered the variables included in the interaction terms (i.e., RBI and corruption).

Hypothesis Testing

Table 1 shows the means per country for the main variables of our model, and Table 2 shows the aggregated means, standard deviations and correlations among variables. As we expected, RBI was negatively correlated with affective commitment and positively with continuance commitment. However, it did not correlate significantly with normative commitment. Corruption, in turn, was significantly correlated with both continuance and normative commitment, but not with affective commitment.

Hypothesis 1 proposes that societal inequality has a direct and positive relationship with RBI. Results show that societal inequality has a statistically significant, positive relation with RBI (B = 0.02, p = 0.002). Thus, Hypothesis 1 is supported (see Table 3).

Hypothesis 2 suggests that corruption moderates the mediating relationship of societal inequality and continuance commitment through RBI, such that the positive RBI–continuance commitment link is stronger for countries with higher corruption levels. Results show that the moderation coefficient of corruption and RBI is positive and significant (B = 0.14, p < 0.001), providing initial support for Hypothesis 2. Similarly, the index of moderated mediation is also positive and significant [b = 0.003, 95% CI (0.001, 0.007)], providing additional support for Hypothesis 2. Further exploration of the results shows that the moderated mediation index is significant only at medium and high levels of corruption [blow corruption = 0.000, (− 0.003, 0.003); bmedium corruption = 0.003, (0.001, 0.006); bhigh corruption = 0.006, (0.002, 0.011)] (Fig. 1).

Hypothesis 3 predicts that corruption moderates the relationship of societal inequality and affective commitment mediated by RBI, such that the negative relationship between RBI and affective commitment is stronger in countries with low corruption. Results of the moderated mediation model show that corruption significantly moderates the link between RBI and affective commitment (B = 0.13, p < 0.001), which provides initial support for Hypothesis 3. Furthermore, the index of moderated mediation is significant [b = 0.003, 95% CI (0.001, 0.006)], further supporting Hypothesis 3. Additional inspection of the findings shows that as corruption increases, the effect of corruption is less pronounced [blow corruption = − 0.011, (− 0.018, − 0.004); bmedium corruption = − 0.008, (− 0.013, − 0.003); bhigh corruption = − 0.005, (− 0.009, − 0.002)] (Fig. 2).

Finally, Hypothesis 4 suggests that corruption moderates the mediated relationship of societal inequality and normative commitment through RBI, such that as corruption increases, the negative effect of RBI on normative commitment decreases. Contrary to our expectations, results show that the interaction between RBI and corruption on normative commitment is not significant (B = 0.05, p = 0.12), and neither is the index of moderated mediation [b = 0.001, 95% CI (− 0.0004, 0.0031)].

Post-Hoc Analyses

There is strong evidence in the literature (Goldman et al., 2006) that various forms of discrimination at work tend to affect female employees more strongly than their male counterparts. Our findings presented in Table 3 provide initial evidence for this, as gender was significantly correlated with most of the outcome variables studied. We therefore conducted additional post-hoc analyses to explore the role of gender in our model.

Results from ANOVA show that there are indeed significant differences between male and female employees for each of the four outcome variables. Thus, women in our sample perceived higher levels of RBI (MRBI_female = 3.74, SD = 1.60) than men (MRBI_male = 3.40, SD = 1.57; F(1, 689) = 7.82, p = 0.005). They also reported higher levels of continuance commitment (Mcontcomm_female = 4.64, SD = 1.22; Mcontcomm_male = 4.43, SD = 1.15; F(1, 689) = 5.32, p = 0.021). Conversely, men showed higher levels of both affective commitment (Maffcomm_male = 4.50, SD = 1.32; Maffcomm_female = 4.20, SD = 1.29; F(1, 689) = 9.15, p = 0.003) and normative commitment (Mnormcomm_male = 4.07, SD = 1.03; Mnormcomm_female = 3.84, SD = 1.07; F(1, 689) = 8.59, p = 0.003).

Drawing on these results and on the inequality literature which suggests that inegalitarian institutional systems may affect women more heavily (Ridgeway, 2011), we also examined whether gender would moderate the relationship between societal inequality and RBI, between RBI and organizational commitment or both. We applied the same procedure used for testing our moderating hypotheses, this time using Model 70 in our analyses. This model enabled us to test the interactive effect of gender on our moderated mediation model. Results confirm that the positive relation between societal inequality and RBI is significantly moderated by gender (B = 0.004, p = 0.002). Further simple slopes analysis shows that only the slope for women is significant (Bfemale = 0.05, p < 0.001; Bmale = 0.005, p = 0.63).

We also explored the possibility that gender played a role in the moderated relation between RBI and organizational commitment. Specifically, we expected that in societies with higher levels of corruption, the positive relationship between RBI and continuance commitment would be stronger for women, as this type of commitment signals a lack of employment alternatives. Contrary to our expectations, the interaction was not significant (B = 0.003, p = 0.61). Thus, while women tend to report higher levels of continuance commitment than men, this is not explained by RBI or corruption levels.

Summary of Results

We find that country-level inequality has a clear relationship with the degree of unequal HR practices reported by the participants of this study. Respondents from organizations in South Africa (high inequality), for example, report much higher RBI than their German counterparts (low country-level inequality). We further show a subsequent relationship with respondents’ organizational commitment, contingent on country corruption levels. Employees who reported extensive unequal HR practices (high RBI) were more likely to feel that they had to stay in their organization (continuance commitment) if general country corruption levels were high, but not if corruption levels were low. RBI also played a role in the link between country-level inequality and affective commitment. Thus, employees were less likely to feel involved and enjoy membership in their organization if RBI was high, but in this case, increasing levels of country corruption reduced this negative relationship. Finally, we found that employees experienced less normative commitment when they perceived higher levels of RBI in their organizations, but that country-level corruption played no role in this relationship. We find that women perceive more unequal treatment than men across all the nations studied.

Discussion

The intention of this work was to investigate how RBI in the workplace relates to employee commitment, and the role of societal-level factors such as corruption and inequality in fostering or weakening the role of RBI in these relationships. We found that employees see more RBI in countries with high societal inequality. Further, while we observe lower affective and normative commitment and higher continuance commitment when RBI increases, the strength of the relationship is contingent on societal levels of corruption.

By focusing on five different nations with varying degrees of societal inequality, our results support the notion that when large disparities exist in income, access to health care and education, this inequality can persist in organizational practices. Inequality in society appears to be related to the practice of using social ties in decision making at an institutional level (Hudson & Claasen, 2017; Khatri et al., 2006). We show that this is reflected in the way employees perceive HR decisions. Our post-hoc analysis reveals that gender might be one of the more salient aspects of societal inequality, leading to a much stronger effect on women’s perception of RBI than men’s. For example, in highly unequal countries such as South Africa, employees reported high levels of RBI, and even more so for South African women. In countries where inequality is less embedded, such as Russia or Germany, reported RBI levels were lower, albeit still higher for women than for men.

The second principal finding concerns the relationship between RBI and different types of organizational commitment. Respondents from countries with higher corruption levels reported stronger continuance commitment when their organization engaged in more RBI. This result is surprising because we would not expect to link unequal HR practices to higher commitment in general (Hudson et al., 2019; Khatri & Tsang, 2003; Pearce et al., 2000). However, by studying this relationship in its societal context, we are able to show that it is contingent on factors external to the organization—namely, the level of country corruption. Continuance commitment rests on an assessment of the costs and benefits of leaving one’s organization. Thus, in highly corrupt societies, employees may consider that they will encounter the same relation-based obstacles faced in their current company when seeking a job elsewhere (Puffer & McCarthy, 2011). In contrast, in countries where corruption is low, and meritocratic procedures for recruitment elsewhere are more likely, employees will not need to remain in an organization with high RBI.

Country corruption levels also affect the relationship between RBI and affective commitment. Specifically, in corrupt contexts, relation-based practices are more accepted in society in general. Thus, because there is less dissonance between RBI and societal norms, affective commitment is less negatively influenced. However, employees in low-corruption environments will find high levels of organizational RBI abnormal. The contrast between societal and organizational norms will create cognitive dissonance, known to have negative impacts on affect (Festinger, 1957), and so low corruption will strengthen the negative relationship between RBI and affective commitment.

Finally, to provide a full picture of RBI and corruption’s interactive effects on commitment, we examined the relationship between RBI and normative commitment, a relatively under-researched commitment dimension (Meyer & Parfyonova, 2010). RBI has a weak negative relationship with normative commitment, but corruption plays no role in this link. Research into the antecedents of normative commitment indicates that it is related to family (Allen & Meyer, 1990) or cultural (Bergman, 2006; Meyer et al., 2012) factors. We observe that the means of normative commitment vary according to country (see Table 2), indicating that culture might be an interesting predictor to examine (Bergman, 2006; Fischer & Mansell, 2009).

While the focus of this paper was not gender inequality, our results indicate that societal inequality plays a stronger role in women’s (vs. men’s) perception of RBI in their organizations. We also note that women report lower affective and normative commitment and higher continuance commitment, indicating that they may perceive fewer opportunities if they quit. These results add to the long-standing stream of research into gender inequality (Gutek et al., 1996; Kelan, 2008), confirming not only that women experience societal inequality more strongly (Goldman et al., 2006), but also that they suffer more relation-based organizational inequality.

Implications for Theory and Practice

Inequality is on the rise globally (Piketty, 2015), and in the coming years a deeper understanding of how societal inequality will affect organizations and their employees will be crucial in the field of business ethics. However, research remains scant in this area (Bapuji et al., 2020a), often focusing solely on income inequality. Therefore, one of the principal contributions of our work is to the emerging research on the nexus between societal inequality and employee outcomes (Bapuji et al., 2020a; Beal & Astakhova, 2017). We show that societal inequality is related to increased employee perceptions of RBI within organizations, which plays a subsequent role in employee commitment. Thus, we are able to link quantitative scores of inequality in incomes and access to health and education, on the one hand, to perceptions of inegalitarian organizational practices on the other, which in turn play a role in employee commitment.

The second contribution is to clarify the nature of perceived unequal HR practices based on social ties that are not particular to a type of relationship—family, friendship or cronyism. By moving away from a focus on the relationship itself, we have delineated a set of practices that employees can identify as inegalitarian, irrespective of whether they occur, for example, between family members within a family-owned business (Spranger et al., 2012) or whether that behavior is oriented toward cronies in publicly owned institutions such as schools (Turhan, 2014).

Our third contribution furthers the body of research on the effect of phenomena such as nepotism, favoritism and cronyism on employee outcomes (Hudson et al, 2019; Pearce et al., 2000). Research has shown evidence of detrimental effects of such phenomena in the workplace. However, recent research points to a more nuanced picture of the relationship between the use of social ties at work and outcomes when other factors are considered. By examining five countries and a broader set of social ties in our study, we confirm that external factors, specifically country-level corruption, play an important role in shaping the relationship between RBI and employee outcomes. In other words, employees in distinct societal settings will respond differently to RBI, with consequent effects on their commitment.

Finally, we offer a methodological contribution to research on nepotism, favoritism and cronyism by providing a new perceptual measure of unequal HR practices. This instrument will enable scholars to investigate such phenomena in a variety of contexts.

The implications of these findings for organizations are that it would be advisable to provide awareness training and embed a culture that fosters meritocratic HR practices in countries with high inequality and corruption. First, managers need to be aware that in countries where societal inequality is high, local HR departments are more likely to make decisions based on relationships rather than merit. Some global corporations are beginning to implement policies to address societal inequality across their supply chains (e.g. McKeever, 2021) to ensure a living wage and inclusivity in terms of race, gender identity, disability and sexual orientation. However, organizations have not begun to address inequality based on relationships, despite phenomena such as favoritism being widespread. For example, Reinsch and Gardner (2014) reported that 92% of senior business executives in their study had observed favoritism, with around a quarter engaging in it themselves. RBI is often linked to the behavior of particular individuals and is therefore difficult to identify at an organizational level. Organizations that want to root out RBI in the workplace need to provide a platform where employees can safely speak up about such issues without fear of retribution. Such initiatives could be a start to creating a corporate culture that makes RBI unacceptable. Second, when employees perceive unequal organizational practices, this has a negative effect on affective commitment. Even in countries with high corruption levels, where engaging in RBI is more acceptable, it has detrimental effects. When corruption levels are low, the effects are very damaging to affective commitment, meaning that employees feel less engaged and performance will deteriorate. Our results on continuance commitment also have implications for organizations, as they demonstrate that people in contexts of high RBI and corruption stay because they have to, not because they are emotionally committed to their work. Therefore, organizations engaging in unequal relation-based practices need to be aware that some employees remain not out of loyalty but because of lack of alternatives. When market conditions change and opportunities arise, these employees may be more likely to quit.

Limitations and Future Research

The topic of unequal HR practices within organizations is a sensitive one, and therefore using anonymous questionnaires to a cross-section of employees in different organizations was one way of overcoming the difficulties associated with a willingness to report truthfully about such phenomena. However, with this design comes the issue of common methods bias (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Although we took steps to overcome this weakness, future studies could usefully examine RBI using alternative designs, such as experiments or qualitative in-depth interviews to explore in greater detail the interplay between societal inequality, corruption and RBI.

Another methodological limitation is the number of individual level controls that we used in our analyses. Hence, while we controlled for gender and attitude toward RBI, other factors like education, job position or socio-economic status might also play a role in shaping how people react to inequality at work (Bowles et al., 2005; Chen et al., 2011). Previous studies have found that individuals with low income tend to be more resentful about inequality than those with higher income (Fisman et al., 2005), potentially affecting how committed they are at work once they feel the shadow of inequality. Thus, future research could explore the influence of these factors on the relationship between societal inequality, RBI, and organizational commitment.

Recent work has suggested that societal inequality and inequality in organizations are linked (Beal & Astakhova, 2017), and that employee-level interactions are affected by inequality (Bapuji, 2015). Because this work is still in its infancy, the investigation of other employee outcomes such as work–life balance, job satisfaction or deviance could usefully inform knowledge and practice. Equally, this body of work has begun to investigate how company-level unequal practices influence society (Bidwell et al., 2013; Cobb, 2016). However, our study only examines the former phenomenon; thus, further studies taking a longitudinal approach could shed light on the causal links between societal and organizational inequality.

Rising inequality is one of the major challenges in the world today. It is therefore vital that management and organizational research develops a robust understanding of how it is perpetuated by organizations and how it permeates the activities and practices within them. We hope that this paper acts as a building block in developing the understanding of inequality and its effects in the workplace.

Notes

We transformed the corruption scores to reflect levels of corruption rather than levels of transparency, as is the case for the Corruption Index calculated by Transparency International.

References

Allen, N. J., & Meyer, J. P. (1990). The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 63(1), 1–18.

Amis, J. M., Mair, J., & Munir, K. A. (2020). The organizational reproduction of inequality. Academy of Management Annals, 14(1), 1–36.

Andrews, T. G., & Htun, K. T. (2018). Economic inequality, cultural orientation and base-of-pyramid employee performance at the MNC subsidiary: A multi-case investigation. Management International Review, 58(2), 337–357.

Ang, Y. Y. (2020). China’s gilded age: The paradox of economic boom and vast corruption. Cambridge University Press.

Arun, N. (2019). State capture: Zuma, the Guptas, and the sale of South Africa. BBC News. Retrieved July 15, 2019, from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-48980964

Ashforth, B. E., & Anand, V. (2003). The normalization of corruption in organizations. Research in Organizational Behavior, 25, 1–52.

Ashforth, B. E., Gioia, D. A., Robinson, S. L., & Trevino, L. K. (2008). Reviewing organizational corruption. Academy of Management Review, 33(3), 670–684.

Aßländer, M., & Hudson, S. (2017). Handbook of business and corruption: Cross-sectoral experiences. Emerald Publishing Limited.

Atkinson, A. B., Piketty, T., & Saez, E. (2011). Top incomes in the long run of history. Journal of Economic Literature, 49(1), 3–71.

Bapuji, H. (2015). Individuals, interactions and institutions: How economic inequality affects organizations. Human Relations, 68(7), 1059–1083.

Bapuji, H., Ertug, G., & Shaw, J. D. (2020a). Organizations and societal economic inequality: A review and way forward. Academy of Management Annals, 14(1), 60–91.

Bapuji, H., Patel, C., Ertug, G., & Allen, D. G. (2020b). Corona crisis and inequality: Why management research needs a social turn. Journal of Management, 46(7), 1205–1222.

Beal, B. D., & Astakhova, M. (2017). Management and income inequality: A review and conceptual framework. Journal of Business Ethics, 142(1), 1–23.

Becker, T. (2019). Russia’s macroeconomy—a closer look at growth, investment, and uncertainty. Stockholm Institute of Transition Economics, Working Paper. 49.

Bedford, O. (2011). Guanxi-building in the workplace: A dynamic process model of working and backdoor guanxi. Journal of Business Ethics, 104, 149–158.

Bergman, M. E. (2006). The relationship between affective and normative commitment: Review and research agenda. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27(5), 645–663.

Bhorat, C., Cassim, A., & Hirsch, A. (2014). Policy coordination and growth traps in a middle-income setting—The case of South Africa. Wider working paper 155/2014. UNU-WIDER.

Bidwell, M., Briscoe, F., Fernandez-Mateo, I., & Sterling, A. (2013). The employment relationship and inequality: How and why changes in employment practices are reshaping rewards in organizations. Academy of Management Annals, 7(1), 61–121.

Birkenstock, G. (2013). Examining nepotism in Germany. DW. Retrieved January 5, 2013, from https://www.dw.com/en/examining-nepotism-in-germany/a-16783849.

Boutilier, R. (2009). Globalization and the careers of Mexican knowledge workers: An exploratory study of employer and worker adaptations. Journal of Business Ethics, 88, 319–333.

Bowles, S., Gintis, H., & Osborne Groves, M. (Eds.). (2005). Unequal chances: Family background and economic success. Princeton University Press.

Brodbeck, F. C., Frese, M., & Javidan, M. (2002). Leadership made in Germany: Low on compassion, high on performance. Academy of Management Executive, 16(1), 16–30.

Burhan, O. K., van Leeuwen, E., & Scheepers, D. (2020). On the hiring of kin in organizations: Perceived nepotism and its implications for fairness perceptions and the willingness to join an organization. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 161, 34–48.

Butler, B. (2020). Frydenberg’s changes to shareholder class actions smack of ‘cronyism’, lawyers say. The Guardian. Retrieved May 25, 2020, from https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2020/may/25/frydenbergs-changes-to-shareholder-class-actions-smack-of-cronyism-lawyers-say.

Case A. & Deaton, A. (2020). How healthcare costs hurt American workers and benefit the wealthy. Time. Retrieved February 20, 2020, from https://time.com/5785945/health-care-problems-america/.

Chalabi, M. (2017). Measuring nepotism: is it more prevalent in the US than in other countries? The Guardian. Retrieved March 24, 2017, from https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2017/mar/24/nepotism-data-ivanka-trump.

Chen, C. W. (2014). Are workers more likely to be deviant than managers? A cross-national analysis. Journal of Business Ethics, 123(2), 221–233.

Chen, C. C., Chen, X.-P., & Huang, S. (2013). Chinese guanxi: An integrative review and new directions for future research. Management & Organization Review, 9(1), 167–207.

Chen, C., & Godkin, L. (2001). Mianzi, guanxi, and western prospects in China. International Journal of Management, 18(2), 139–147.

Chen, Y., Friedman, R., Yu, E., & Sun, F. (2011). Examining the positive and negative effects of guanxi practices: A multi-level analysis of guanxi practices and procedural justice perceptions. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 28(4), 715–735.

Cialdini, R. B., & Goldstein, N. J. (2004). Social influence: Compliance and conformity. Annual Review of Psychology, 55(1), 591–621.

Clark, C. (2019). South Africa Confronts a Legacy of Apartheid: Why land reform is a key issue in the upcoming election. The Atlantic. Retrieved, Dec 14, 2019 from https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2019/05/land-reform-southafrica-election/586900/.

Cobb, A. (2016). How firms shape income inequality: Stakeholder power, executive decision making, and the structuring of employment relationships. Academy of Management Review, 41(2), 324–348.

Collins, C., Ocampo, O., & Paslaski, S. (2020). Billionaire bonanza 2020—Wealth windfalls, tumbling taxes and pandemic profiteers. Inequality. Retrieved from https://inequality.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Billionaire-Bonanza-2020-April-21.pdf.

Corak, M. (2013). Income inequality, equality of opportunity, and intergenerational mobility. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 27(3), 79–102.

Crawford, C., Gregg, P., Macmillan, L., Vignoles, A., & Wyness, G. (2016). Higher education, career opportunities, and intergenerational inequality. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 32(4), 553–575.

Diamantopoulos, A., & Winklhofer, H. M. (2001). Index construction with formative indicators: An alternative to scale development. Journal of Marketing Research, 38(2), 269–277.

DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160.

Dzansi, L. W., Chipunza, C., & Monnapula-Mapesela, M. (2016). Municipal employees’ perceptions of political interference in human resource management practices: Evidence from the free state province in South Africa. International Business & Economics Research Journal, 15(1), 15–26.

Estlund, C. (2010). Regoverning the workplace. Yale University Press.

Felbermayr, G., Baumgarten, D., & Lehwald, S. (2014). Increasing wage inequality in Germany: What role does global trade play? AEI. http://aei.pitt.edu/74112/.

Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford University Press.

Fischer, M. M. J. (2003). Emergent forms of life and the anthropological voice. Duke University Press.

Fischer, R., & Mansell, A. (2009). Commitment across cultures: A meta-analytical approach. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(8), 1339–1358.

Fisman, R., Jakiela, P., Kariv, S., & Markovits, D. (2015). The distributional preferences of an elite. Science, 349(6254), 1300–1307.

Frege, C., & Godart, J. (2014). Varieties of capitalism and job quality: The attainment of civic principles at work in the United States and Germany. American Sociological Review, 79(5), 942–965.

Fukuyama, F. (2001). Social capital, civil society and development. Third World Quarterly, 22(1), 7–20.

Galbraith, J., & Choi, J. (2020). The politics of American inequality. Intereconomics, 55(1), 63–64.

GAN Business Anti-Corruption Portal (2018). Germany corruption report. Retrieved from https://www.ganintegrity.com/portal/country-profiles/germany/

Garlow, S. (2018). Gender equality stalls in the U.S., Stanford report finds. Stanford News. Retrieved from https://news.stanford.edu/2018/03/16/gender-equality-stalls-u-s-stanford-report-finds.

Global Legal Insights (2021). Bribery & Corruption—Germany. Retrieved from https://www.globallegalinsights.com/practice-areas/bribery-and-corruption-laws-and-regulations/germany

Goldman, B. M., Gutek, B. A., Stein, J. H., & Lewis, K. (2006). Employment discrimination in organizations: Antecedents and consequences. Journal of Management, 32, 786–830.

Greene, W. (2008). Three ideologies of individualism: Toward assimilating a theory of individualisms and their consequences. Critical Sociology, 34(1), 117–137.

Guriev, S., & Zhuravskaya, E. (2010). Why Russia is not South Korea. Journal of International Affairs, 63(2), 25–39.

Gutek, B. A., Cohen, A. G., & Tsui, A. (1996). Reactions to perceived sex discrimination. Human Relations, 49(6), 791–813.

Hardwick, N. (2014). Reviewing the changing situation of women in Russian society. E-International Relations. Retrieved December 20, 2014, from https://www.e-ir.info/2014/12/20/reviewing-the-changing-situation-of-women-in-russian-society/

Harman, H. H. (1976). Modern factor analysis. University of Chicago Press.

Hauser, R. (2004). The personal distribution of economic welfare in Germany: How the welfare state works. Social Indicators Research, 65(1), 1–25.

Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Publications.

Hayes, N., Introna, L. D., & Kelly, P. (2018). Institutionalizing inequality: Calculative practices and regimes of inequality in international development. Organization Studies, 39(9), 1203–1226.

Heneman, R. L., Greenberger, D. B., & Anonyuo, C. (1989). Attributions and exchanges: The effects of interpersonal factors on the diagnosis of employee performance. Academy of Management Journal, 32(2), 466–476.

Hitt, M. A., Ahlstrom, D., Dacin, M. T., Levitas, E., & Svobodina, L. (2004). The institutional effects on strategic alliance partner selection in transition economies: China vs. Russia. Organization Science, 15(2), 173–185.

Horsley, J. P. (2019). Transparency, accountability and access to information. Handbook on human rights in China. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Hudson, S., & Claasen, C. (2017). Nepotism and cronyism as a cultural phenomenon? The handbook of business and corruption (pp. 95–118). Emerald Publishing Limited.

Hudson, S., González-Gómez, H. V., & Claasen, C. (2019). Legitimacy, particularism and employee commitment and justice. Journal of Business Ethics, 157(3), 589–603.

Hundenborn, J., Leibbrandt, M., & Woolard, I. (2018). Drivers of inequality in South Africa. WIDER working paper 2018/162. UNU-WIDER.

Jaros, S., & Culpepper, R. A. (2014). An analysis of Meyer and Allen’s continuance commitment construct. Journal of Management & Organization, 20(1), 79–99.

Jennings, R. (2018). Despite China’s fast-growing wealth, millions still remain poor. Forbes. Retrieved February 4, 2018, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/ralphjennings/2018/02/04/why-tens-of-millions-remain-poor-in-china-despite-fast-growing-wealth/#68a390d17e9e.

Jiang, L., & Probst, T. M. (2017). The rich get richer and the poor get poorer: Country-and state-level income inequality moderates the job insecurity-burnout relationship. Journal of Applied Psychology, 102(4), 672–681.

Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A., & Mastruzzi, M. (2008). Governance matters VII: Aggregate and individual governance indicators 1996–2007. World Bank. Retrieved from http://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/pdf/GovernanceMattersVII.pdf

Kelan, E. K. (2008). The discursive construction of gender in contemporary management literature. Journal of Business Ethics, 81(2), 427–445.

Khanna, P. & Francis, D. (2016). These 25 companies are more powerful than many countries. Foreign Policy. Retrieved March 15, 2016, from https://foreignpolicy.com/2016/03/15/these-25-companies-are-more-powerful-than-many-countries-multinational-corporate-wealth-power/.

Khatri, N. (2016). Definitions of cronyism, corruption, and crony capitalism. Crony capitalism in India (pp. 3–7). Palgrave Macmillan.

Khatri, N., & Tsang, E. W. K. (2003). Antecedents and consequences of cronyism in organizations. Journal of Business Ethics, 43(4), 289–303.

Khatri, N., Tsang, E. W., & Begley, T. M. (2006). Cronyism: A cross-cultural analysis. Journal of International Business Studies, 37(1), 61–75.

Khuzwayo, Z. (2016). Separate space: An approach to addressing gender inequality in the workplace. Journal of International Women’s Studies, 17(4), 91–101.

Kochan, T., & Osterman, P. (1994). The mutual gains enterprise: Forging a winning partnership among labor, management, and government. Harvard Business School Press.

Kopecky, P. (2011). Political competition and party patronage: Public appointments in Ghana and South Africa. Political Studies, 59, 713–732.

Lahsen, M. (2005). Technocracy, democracy, and U.S. climate politics: The need for demarcations. Science, Technology, & Human Values, 30(1), 137–169.

Ledeneva, A. V. (2013). Can Russia modernise? Sistema, power networks and informal governance. Cambridge University Press.

Li, A., Bagger, J., & Cropanzano, R. (2017). The impact of stereotypes and supervisor perceptions of employee work–family conflict on job performance ratings. Human Relations, 70(1), 119–145.

McCarthy, N. (2020). The most corrupt States in America. Forbes. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/isabeltogoh/2020/07/05/12-people-injured-following-south-carolina-club-shooting/#30a0a3a91328.

McKeever, V. (2021, January 21). Unilever aims to train up 10 million young people for work in strategy to tackle inequality. CNBC. Retrieved from https://www.cnbc.com/2021/01/21/unilever-strategy-to-tackle-inequality-includes-training-young-people.html.

Merchant, M. (2016). A captured state? Corruption and economic crime, in Carbone. South Africa: The need for change (pp. 35–54). Ledizioni Ledi.

Metz, T. (2011). Ubuntu as a moral theory and human rights in South Africa. African Human Rights Law Journal, 11, 532–559.

Meyer, J. P., & Parfyonova, N. M. (2010). Normative commitment in the workplace: A theoretical analysis and re-conceptualization. Human Resource Management Review, 20(4), 283–294.

Meyer, J. P., Stanley, D. J., Jackson, T. A., McInnis, K. J., Maltin, E. R., & Sheppard, L. (2012). Affective, normative, and continuance commitment levels across cultures: A meta-analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(2), 225–245.

Michailova, S., & Worm, V. (2003). Personal networking in Russia and China: Blat and Guanxi. European Management Journal, 21(4), 509–519.

Moorman, R. H. (1991). Relationship between organizational justice and organizational citizenship behaviors: Do fairness perceptions influence employee citizenship? Journal of Applied Psychology, 76(6), 845–855.

National Conference of State Legislatures. (2020). Nepotism restrictions. Retrieved July 13, 2020, from https://www.ncsl.org/research/ethics/50-state-table-nepotism-restrictions.aspx

Novotney, A. (2008). What’s behind American consumerism? American Psychological Association, 39(7), 40.

OECD (2012). HRM country profiles: Germany. Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/gov/pem/OECD%20HRM%20Profile%20-%20Germany.pdf

OECD (2015). In it together. Why less inequality benefits all. Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/germany/OECD2015-In-It-Together-Highlights-Germany.pdf

OECD (2018). Germany’s strong anti-bribery enforcement against individuals needs to be matched by comparably strong enforcement against companies. Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/corruption/germany-s-strong-anti-bribery-enforcement-against-individuals-needs-to-be-matched-by-comparably-strong-enforcement-against-companies.htm.

OECD (2020). OECD Employment Outlook 2020: Worker security and the Covid-19 crisis. How does Germany compare? Retrieved from https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=134_134914-ji1sq3fttc&title=Employment-Outlook-Germany-EN (retrieved July 20, 2020).

Open Government Partnership (2014). South Africa—Progress report 2013–2014. Retrieved from www.opengovpartnership.org/sites/default/files/IRMReport_SouthAfrica_final.pdf.

Orthofer, A. (2015). Private wealth in a developing country: A South African perspective on Piketty. Economic Research Southern Africa, Working Paper 564. Retrieved from https://wid.world/document/orthofer-anna-2015-private-wealth-in-a-developing-country-a-south-african-perspective-on-piketty-ersa-working-paper-564/

Pearce, J. L., Branyiczki, I., & Bigley, G. A. (2000). Insufficient bureaucracy: Trust and commitment in particularistic organizations. Organization Science, 11(2), 148–162.

Piketty, T. (2015). About capital in the twenty-first century. American Economic Review, 105(5), 48–53.

Piketty, T., & Saez, E. (2003). Income inequality in the United States, 1913–1998. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(1), 1–39.

Pitcher, A. (2012). Was privatisation necessary and did it work? The case of South Africa. Review of African Political Economy, 39(132), 243–260.