Abstract

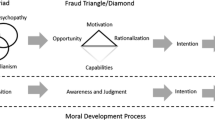

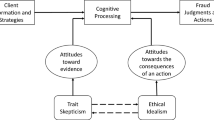

For several decades, most discussion on financial fraud has centered on the fraud triangle, which has evolved over time through various extensions and re-interpretations. While this has served the profession well, the articulation of the human side of the act is indirect and diffused. To address this limitation, this research develops a model to explain the role of human desires, intentions, and actions in indulgence of, or resistance to, the act of financial fraud. Evidence from religion, philosophy, sociology, neurology, behavioral economics, and social psychology is integrated to develop and support an alternative fraud model, called the disposition-based fraud model (DFM). To articulate the model, its two primary components, disposition and temptation, are further developed and extended. Although the DFM is generally applicable to any act of fraud, this paper focuses on executive fraud. The similarities and differences between the DFM and extant fraud models are discussed. Importantly, in light of the DFM, a re-interpretation of the fraud triangle is made to improve our understanding of the human element in it. Additionally, potential implications of the model for corporate governance are discussed, suggestions for further research are offered, and the DFM’s strengths and limitations are noted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Table 5 of the report (p. 14) shows that an overwhelming majority was composed of senior management, including vice-president, controller, CEO, CFO, and CEO/CFO.

This notion is supported by the studies suggesting tone at the top as a key fraud risk factor (see, e.g., Apostolou et al. 2001).

According to the New Testament, temptation approaches human beings in diverse ways and tries to motivate them to follow the voice of egoism and anxiety and strive for power and profit instead of listening to conscience.

According to Kennett (2001, p. 57), the craving provides a context in which the less desirable object becomes more attractive without the benefit of any supporting change in beliefs.

This state of stability is relative, not absolute, for at times there may be perfectly valid grounds for the agent to revise his intentions without breaking his resolve.

This analogy is made by Kahneman (2011).

The valuations of those who had no chance to ring the bell are the same as those of the control group that did not have to wait.

Thus, rationalizations aimed to avoid cognitive dissonance make the compromise feasible because they “endorse” the moral compromise as justified.

See Chapter 8 in Ramamoorti et al. (2013), for a detailed discussion on emotional manipulation in fraud.

Hume first published The Treatise of Human Nature during the 1730s.

For a discussion of disposition and its relationship with morality, see Raval (2013).

The classification, R(s) and R(t), in Raval (2013) is simplified here as P(E) and P(I), respectively, for ease of communication and recall.

Interestingly, other religions also point to the role of disposition. For example, Rumi (Baldock 2006, pp. 164–167) suggests this classification: Angels, Descendents of Adam, and Beasts, roughly comparable to the enlightened, passionate, and indolent disposition, respectively.

For a detailed discussion, see Raval (2013, pp. 5–6.)

I consider self-control and self-regulation as synonyms.

Kennett (2001) argues that the yielding to an urge results when “motivating reasons” outpace “normative reasons.”

Referring to Vedic scriptures, Sivananda (1954, p. 42) identifies two approaches to resist temptation: internally induced Dama (restraining the senses) and externally induced Sama (neglecting or withdrawing from the tempting stimuli).

The founder of the Jesuits, St. Ignatius of Loyola, writes in his widely known Spiritual Exercises (1548): I resist [an evil thought] promptly and it is overcome; the second I resist it, it recurs again and again and I keep on resisting until the thought goes away defeated.

Buddha described the discipline of moderation as madhyamarg, which translates as the middle road.

The use of the term ego in ego depletion is not clear. Ego in Sanskrit equates to Aham, or pride, which is a dispositional property of Swabhava, or one’s character.

Prison-Bound KPMG Ex-Partner Remorseful for Insider Tips, M. Rapoport, The Wall Street Journal, June 26, 2014, C3.

According to the 2014 ACFE Report to the Nation (p. 58), only 5 % of the fraudsters in their study had been convicted of a fraud-related offense prior to committing the crimes in their study.

In a verdict issued in the Federal Court in Manhattan, the jury found five former employees guilty of collaborating with Bernard Madoff in his Ponzi scheme: two computer programmers (Jerome O’Hara and George Perez), two portfolio managers (Annette Bongiorno and JoAnn Crupi), and operations director Daniel Bonventre. (Jury Finds Staff Aided Madoff Con, The Wall Street Journal, Tuesday, March 25, 2014, A1-2).

This trend seems pervasive in financial reporting fraud. During the period 1998–2007, the SEC named the CEO and/or CFO in 89 % of fraud cases for some level of involvement in financial fraud (Beasley et al. 2010).

Zero tolerance for breakdowns in resolve would lead to strong frontline safeguards, but once these are broken, there is no further diligence imposed. Breaking the barriers, however well-guarded, could lead to the feeling that the resolve is no longer relevant. It is also likely that the person would lower the threshold on seeking feedback of further divergence, if any, since the breakdown has already been accepted.

An argument can be made, however, that greed drives the perception of short-term rewards as more attractive than long-term gains.

References

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211.

Albrecht, W. S., Albrecht, C. C., & Albrecht, C. O. (2004). Fraud and corporate executives: Agency, stewardship and broken trust. Journal of Forensic Accounting, 5, 109–130.

Albrecht, W. S., Howe, K. R., & Romney, M. B. (1984). Deterring fraud: The internal auditor’s perspective. Altamonte Springs, FL: The Institute of Internal Auditors’ Research Foundation.

Amernic, J., & Craig, R. (2010). Accounting as a facilitator of extreme narcissism. Journal of Business Ethics, 96(1), 79–93.

Apostolou, B. A., Hassell, J. H., Webber, S. A., & Sumners, G. E. (2001). The relative importance of fraud risk factors. Behavioral Research in Accounting, 13, 1–24.

Arjoon, S. (2006). Striking a balance between rules and principles-based approaches for effective governance: A risks-based approach. Journal of Business Ethics, 68, 53–82.

Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE). (2014). Report to the nations on occupational fraud and abuse. Austin, TX: The Association of Certified Fraud Examiners.

Aurobindo, S. (1996). Essays on the Gita (First Series). Pondicherry, India: Sri Aurobindo Ashram Press.

Baldock, J. (2006). The essence of RUMI. London, UK: Arcturus.

Bandura, A. (2002). Selective moral disengagement in the exercise of moral agency. Journal of Moral Education, 31(2), 101–119.

Barnard, J. W. (2009). Narcissism. Over-optimism, fear, anger, and depression: The interior lives of corporate leaders, University of Cincinnati Law Review, 77, 405–430.

Baumeister, R. F. (1996). Evil: Inside human violence and cruelty. New York, WH: Freeman.

Baumeister, R. F., Bratslavski, E., Muraven, M., & Tice, D. M. (1998). Ego depletion: Is the active self a limited resource? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 1252–1265.

Baumeister, R. F., Heatherton, T. F., & Tice, D. M. (1994). Losing control: How and why people fail at self-regulation. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Bazerman, M., & Tenbrunsel, A. (2011). The Rotman magazine, Spring, p. 53–57.

Beasley, M. S., Carcello, J. V., Hermanson, D. R., & Neal, T. L. (2010). Fraudulent financial reporting 1998–2007: An analysis of U.S. Public Companies, Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission.

Beck, L., & Ajzen, I. (1991). Predicting dishonest actions using the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Research in Personality, 25(3), 285–301.

Bell, T. B., & Carcello, J. V. (2000). Research notes: A decision aid for addressing the likelihood of fraudulent financial reporting. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 19(1), 169–184.

Bem, D. J. & Funder, D. C. (1978). Predicting more of the people more of the time: The search for cross-situational consistencies in behavior. Psychological Review, 85, 485–501.

Berlyne, D. (1980). Conflict, arousal, and curiosity. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Blickle, G., Schlegel, A., Fassbender, P., & Klein, U. (2006). Some personality correlates of business white-collar crime. Applied Psychology, 55(2), 220–233.

Bonger, W. (1905, pub. 1969). Criminality and economic conditions, original version in French, abridged by A. T. Turk. Indiana University Press, Bloomington, Indiana.

Boyle, D. M., DeZoort, F. T., & Hermanson, D. R. (2015). The effect of alternative fraud model use on auditors’ fraud risk judgments. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 34, 578–596.

Bratman, M. (1987). Intentions, plans, and practical reason. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Brinkmann, J. (2005). Understanding insurance customer dishonesty: Outline of a situational approach. Journal of Business Ethics, 61, 183–197.

Buss, D. M., & Craik, K. H. (1983). The act frequency approach to personality. Psychological Review, 90(2), 105–126.

Campbell, K. A. (2015). Can effective risk management signal virtue-based leadership? Journal of Business Ethics, 129, 115–130.

Carpenter, T. D., & Reimers, J. L. (2005). Unethical and fraudulent financial reporting: Applying the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 60(2), 115–129.

Chatterjee, A., & Hambrick, D. C. (2007). It’s all about me: Narcissistic CEOs and their effects on company strategy and performance. Administrative Science Quarterly, 32, 351–386.

Choo, F., & Tan, K. (2007). An “American dream” theory of corporate executive fraud. Accounting Forum, 31(2), 203–215.

Cohen, J. (2005). The vulcanization of the human brain: A neural perspective on interaction between cognition and emotion. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 19, 3–24.

Cohen, J., Ding, Y., Lesage, C., & Stolowy, H. (2010). Corporate fraud and managers’ behavior: Evidence from the press. Journal of Business Ethics, 95, 271–315.

Cressey, D. R. (1953). Other people’s money. New York, NY: Free Press.

Dalal, C. (2015). Novel and conventional methods of audit, investigation and fraud detection (3rd ed.). Gurgaon, India: Wolters Kluwer.

Das, R. C. (1987). The Gita typology of personality. Journal of Indian Psychology, 6(1&2), 7–12.

Dasa, D. G. (1999). Vedic personality inventory (An unpublished manuscript), Bhaktivedanta College.

De Martino, B., Kumaran, D., Seymour, B., & Dolan, R. J. (2006). Frames, biases, and rational decision-making in the human brain. Science, 313, 684–687.

Dorminey, J. W., Fleming, A. S., Kranacher, M., & Riley, R. A, Jr. (2010). Beyond the fraud triangle. The CPA Journal, 80, 17–23.

Dorminey, J. W., Fleming, A. S., Kranacher, M., & Riley, R. A, Jr. (2012). The evolution of fraud theory. Issues in Accounting Education, 27(2), 555–579.

DuBrin, A. J. (2012). Narcissism in the workplace. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

Feng, M., Weili, G., Luo, S., & Shevlin, T. (2011). Why do CFOs become involved in material accounting manipulations? Journal of Accounting and Economics, 51, 21–36.

Figner, B., Knoch, D., Johnson, E. J., Krosch, A. R., Lisanby, S. H., Fehr, E., & Weber, E. U. (2010). Lateral prefrontal cortex and self-control in intertemporal choice. Nature Neuroscience, 13(5), 538–539.

Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Funder & Block. (1989). The role of ego-control, ego-resiliency, and IQ in delay of gratification in adolescence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 1041–1050.

Glimcher, P. W., & Rustichini, A. (2004). Neuroeconomics: The consilience of brain and decision. Science, 306, 447–452.

Gordon, E. A., Henry, E., Louwers, T. J., & Reed, B. J. (2007). Auditing related-party transactions: A literature overview and research synthesis. Accounting Horizons, 21(1), 81–102.

Green, T. H. (1906). Prolegomena to ethics. Charleston, SC: Bibliolife.

Hambrick, D. D., & Mason, P. A. (1984). Upper echelons: The organization as a reflection of its top managers. Academy of Management Review, 9(2), 193–206.

Henry, K. (2009). Leading with your soul. Strategic Finance, 90, 45–51.

Hogan, C. E., Rezaee, Z., Riley, R. A, Jr., & Velury, U. K. (2008). Financial statement fraud: Insights from the academic literature. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 27(2), 231–252.

Holton, R. (2009). Willing, wanting, waiting. Oxford, England (eBook): Oxford University Press.

Hume, D. (2000). A treatise of human nature. In D. F. Norton & M. J. Norton (Eds.). Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press.

Hunt, S. D., & Vitell, S. (1986). A general theory of marketing ethics. Journal of Macromarketing, 6(Spring), 5–16.

Ignatius of Loyola. (1548, 1996). Spiritual exercises. In J. Munitiz & P. Endean (Eds.), Personal writings. Penguin: Armondsworth.

Jackson, R. W., Wood, C. M., & Zboja, J. J. (2013). The Dissolution of ethical decision-making in organizations: A comprehensive review and model. Journal of Business Ethics, 116, 233–250.

Johnson, E. N., Kuhn, J. R., Apostolou, B. A., & Hassell, J. M. (2013). Auditor perceptions of client narcissism as a fraud attitude risk factor. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 32(1), 203–219.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Karniol, R., & Miller, D. (1983). Why not wait? A cognitive model of self-imposed delay termination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45, 935–942.

Katz, L. G. (1993). Disposition: Definitions and implications for early childhood practices. Perspectives from ERIC/EECE, A monograph series No. 4.c.

Katz, L. G., & Raths, J. D. (1985). Dispositions as goals for teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 1(4), 301–307.

Kennett, J. (2001). Agency and responsibility. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Kets de Vries, M. (2004). Organizations on the couch: A clinical perspective on organizational dynamics. European Management Journal, 22, 183–200.

Kets de Vries, M., & Miller, D. (1985). Narcissism and leadership: An object relations perspective. Human Relations, 38, 583–601.

Kirschenbaum, D. S. (1987). Self-regulatory failure: A review with clinical implications. Clinical Psychology Review, 7, 77–104.

Kohlberg, L. (1984). Moral stages and moralization: The cognitive development approach. In L. Kohlberg (Ed.), The psychology of moral development: The nature and validity of moral stages (pp. 170–205). New York, NY: Harper & Row.

Kuhn, T. S. (1962). The structure of scientific revolutions. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Lehrer, J. (2009). How we decide. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Manstead, A., & Van Eekelen, S. (1998). Distinguishing between perceived behavioral control and self-efficacy in the domain of academic achievement intentions and behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 28(15), 1375–1392.

Maphet, H. W., & Miller, A. L. (1982). Compliance, temptation, and conflicting instructions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 18, 1–9.

Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98, 228–253.

Marutham, P., Balodhi, J. P., & Mishra, H. (1998). Sattva, Rajas, Tamas (SRT) inventory. NIHHANS Journal, 16, 15–19.

Matthew, T. (2010). Identifying management training needs for chartered accountants using Trigunas. AIMS International Conference on Value-based Management, (unpublished).

McLure, S. M., Ericson, K. M., Laibson, D. I., Lowenstein, G., & Cohen, J. D. (2007). Time discounting for primary rewards. The Journal of Neuroscience, 27(21), 5796–5804.

McLure, S. M., Laibson, D. I., Lowenstein, G., & Cohen, J. D. (2004). Separate neural systems value immediate and delayed monetary rewards. Science, 306, 503–507.

Miller, G. (2006). The emotional brain weighs its options. Science, 313, 600–601.

Mischel, W. (2014). The marshmallow test: Mastering self-control. New York, NY: Little Brown and Company.

Morales, J., Gendron, Y., & Guenin-Paracini, H. (2014). The construction of the risky individual and vigilant organization: A genealogy of the fraud triangle. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 39, 170–194.

Myrseth, K. O. R., & Fishbach, A. (2009). Self-control: A function of knowing when and how to exercise restraint. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18(4), 247–251.

Nevins, J. L., Bearden, W. O., & Money, B. (2007). Ethical values and long-term orientation. Journal of Business Ethics, 71, 261–274.

Nordgren, L. F., & Chou, E. Y. (2011). The push and pull of temptation: The bidirectional influence of temptation on self-control. Psychological Science, 22(11), 1386–1390.

Paine, L. S. (1994). Managing for organizational integrity. Harvard Business Review, 72(2), 106–117.

Parameswaran, E. G. (1969). Indian psychology—Need for breakthrough an attempt. Research Bulletin: Sun Chiwawitthaya Thang Thale Phuket, 5, 75–80.

Pathak, N. S., Bhatt, I. D., & Sharma, R. (1992). Manual for classifying personality on tridimensions of Gunas—An Indian approach. Indian Journal of Behavior, 16(4), 1–14.

Prescott, W. H. (1847). History of the conquest of Peru. New York, NY: Harper and Brothers.

Ramamoorti, S. (2008). The psychology and sociology of fraud: Integrating the behavioral sciences component into fraud and forensic accounting curricula. Issues in Accounting Education, 23(4), 521–534.

Ramamoorti, S., Morrison, D. E, I. I. I., Koletar, J. W., & Pope, K. R. (2013). A.B.C.’s of behavioral forensics: Applied psychology to financial fraud prevention and detection. Hoboken, NY: Wiley.

Raval, V. (2013). Human disposition and the fraud cycle. International Journal of Applied Behavioral Economics, 2(1), 1–16.

Rockness, H., & Rockness, J. (2005). Legislated ethics: From Enron to Sarbanes-Oxley, the impact on Corporate America. Journal of Business Ethics, 57, 31–54.

Ryle, G. (1949). The concept of mind. London, UK: Hutchinson & Company Ltd.

Schwartz, H. S. (1991). Narcissism project and corporate decay: The case of general motors. Business Ethics Quarterly, 1, 249–268.

Setiya, K. (2007). Reasons without rationalism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Sivananda, Swami. (1954). Mind: Its mysteries & control. Sivanand Nagar, India: The Yoga-Vedanta Forest University.

Skinner, B. F. (1938). The behavior of organisms: An experimental analysis. Cambridge, MA: B.F. Skinner Foundation.

Stanowich, K. E., & West, R. F. (2008). On the relative independence of thinking biases and cognitive ability. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94, 672–695.

Stempel, H. S., Cheston, S. E., Greer, J. M., & Gillespie, C. K. (2006). Further exploration of the Vedic personality inventory: Validity, reliability, and generalizability. Psychological Reports, 70, 1131–1138.

Tang, T. L., & Sutarso, T. (2013). Falling or not falling into temptation? and unethical intentions across gender. Journal of Business Ethics, 116, 529–552.

Thaler, R., & Benartzi, S. (2004). Save more tomorrow: Using behavioral economics to increase employee saving. Journal of Political Economy, 112((Issue 1, Part 2)), 164–187.

Tilak, B. G. (2004). Srimad Bhagvadgita-Rahasya or Karma-yoga-Sastra (B. S. Sukthankar, Trans.). Pune, India: Kesari Press.

Trope, Y., & Fishbach, A. (2000). Counteractive self-control in overcoming temptation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(4), 493–506.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1981). The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice. Science, 211, 453–458.

Van Gils, S., Van Quaquebeke, N., & Van Knippenberg, D. (2010). Tango in the dark. In B. Schyns & T. Hansbrough (Eds.), When leadership goes wrong (pp. 285–303). Charlotte, NC: Information Age.

Van Hook, E., & Higgins, E. T. (1988). Self-related problems beyond the self-concept: Motivational consequences of discrepant self-guides. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 55, 625–633.

Wales, W. J., Patel, P. C., & Lumpkin, G. T. (2013). In pursuit of greatness: CEO narcissism, entrepreneurial orientation, and firm performance variance. Journal of Management Studies, 50, 1041–1069.

Wells, J. T. (1997). Occupation fraud and abuse: How to prevent and detect asset misappropriation, corruption and fraudulent statements. Austin, Texas: Obsidian Publishing Company.

Wolfe, D. T., & Hermanson, D. (2004). The fraud diamond: Considering the four elements of fraud. The CPA Journal, 74, 38–42.

Acknowledgments

I appreciate the helpful comments provided by Andrew Gustafson, Bev Kracher, Ed Morse, George MrKonic, Pamela Murphy, Sanjay Singh, James Weber, an anonymous reviewer, and participants of the roundtable/workshop at the Heider College of Business, Youth Leadership of Omaha, Creighton University Law School, and the Asian World Center, Creighton University. I also gratefully acknowledge the financial support received from the Heider College of Business and the Graduate School at Creighton University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Raval, V. A Disposition-Based Fraud Model: Theoretical Integration and Research Agenda. J Bus Ethics 150, 741–763 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3199-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3199-2