Abstract

Using an international sample of firms from 32 countries, we study the relation between media independence and corporate tax aggressiveness. We measure media independence by the extent of private ownership and competition in the media industry. Using an indicator variable for tax aggressiveness when the firm’s corporate tax avoidance measure is within the top quartile of each country-industry combination, we find strong evidence that media independence is associated with a lower likelihood of tax aggressiveness, after controlling for other institutional determinants, including home-country tax system characteristics. We also find that the effect of media independence is more pronounced when the legal environment is weaker, and when the information environment is less transparent. We contribute to the business ethics literature by documenting the role of independent media as an external monitoring mechanism in constraining corporate tax aggressiveness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

These include but are not limited to editorials in leading news outlets such as Bloomberg’s “The Great Corporate Tax Dodge,” the New York Times’ “But Nobody Pays That,” The Times’ “Secrets of Tax Avoiders,” and the Guardian’s “Tax Gap.”

For example, a recent report by Confederation of Indian Industry (CII) and global services firm Ernst & Young (EY) indicates that countries like India and China are looking at tax base erosion.

A Starbucks spokesperson said “We listened to our customers in December and so decided to forgo certain deductions which would make us liable to pay £10 m in corporation tax this year and a further £10 m in 2014 (emphasis added),” which suggests that Starbucks was not convicted of any tax wrongdoing but voluntarily paid additional taxes. Interestingly, this was Starbucks’ first tax payment in five years, since 2009.

In this paper, we follow Hanlon and Heitzman (2010) and define tax avoidance broadly as the reduction in explicit taxes paid. Hanlon and Heitzman (2010) state that “if tax avoidance represents a continuum of tax planning strategies where something like municipal bond investments are at one end (lower explicit tax, perfectly legal), then terms such as “noncompliance,” “evasion,” “aggressiveness,” and “sheltering” would be closer to the other end of the continuum. Therefore, we define tax aggressiveness as tax planning strategies at the more aggressive end of the tax avoidance spectrum that are more likely to push the envelope of tax law and to include the more aggressive tax-related activities that the media presumably are more concerned about in their coverage.

Although state-owned media may have higher incentives to expose tax avoidance practices, prior literature shows that state ownership of media is associated with higher corruption, thus reducing or completely reversing these incentives (Houston et al. 2011).

Within two days of announcement of the merger between Pfizer and Allergen, The New York Times carried an editorial headlined, “Pfizer’s Big Tax Avoidance Play” (The New York Times, November 24, 2015). In it, the editorial states, “This merger is a tax-dodging maneuver that enriches shareholders and executives while short changing the public and robbing the Treasury …” This is an example of tax aggressive activities becoming headline grabbing newsworthy events in major media outlets.

Potential savings from aggressive tax avoidance strategies can be economically large (Scholes et al. 2014). For example, Bloomberg News reports that Google avoided $2 billion in worldwide income taxes in 2011 by channeling $10 billion of revenue into a Bermuda shell company.

Dowling (2014) characterizes the fair share of tax as the statutory tax rate times a reasonable estimate of the firm’s taxable profits (that is, tax base).

Anecdotal and empirical evidence indicates that the direct costs alone can be quite substantial. For example, in 14 cases of tax sheltering, Wilson (2009) finds that the interest charges paid by firms to tax authorities amounted to 40 % of the tax savings originally generated by the tax shelter transactions. Graham and Tucker (2006) report the case of GlaxoSmithKline P.L.C. in 2004, which owes the IRS $5.2 billion in back taxes and penalties related to a transfer pricing strategy dating back to 1989.

Supporting this notion, Austin and Wilson (2015) find evidence that firms with valuable customer brands engage in lower levels of tax avoidance, due to the threat of reputational damages associated with tax avoidance. In an experimental study, Hardeck and Hertl (2014) also document that media coverage of aggressive corporate tax strategies can affect corporate reputation, and consumers punish tax aggressive companies by lowering their willingness to pay for companies’ products.

For instance, Citizens for Tax Justice reported in February 2012 on General Electric’s low tax rate of two percent over ten years. Despite this negative coverage, General Electric continues to be among the top tax avoiders in another study published in October 2015 (“The use of offshore tax havens by Fortune 500 companies”).

Lanis and Richardson (2014) employ an alternate measure of tax avoidance based on firm tax disputes, in the U.S. This measure is difficult to implement, since our sample covers 32 countries.

The importance of a private and competitive media is widely recognized; it is often called “the fourth estate,” along with the executive, the legislature, and the courts (Djankov et al. 2003).

For more details of the Panama Papers controversy, see ICIJ’s website: https://panamapapers.icij.org/ and Süddeutsche Zeitung’s website: http://panamapapers.sueddeutsche.de/articles/56febff0a1bb8d3c3495adf4/.

Dyck et al. (2010, case summaries) highlight the case of Sprint Corporation, where an article by the New York Times alerted the IRS to the existence of four tax shelters promoted by Ernst and Young, and subsequent IRS investigations charged Sprint’s top executives with personal tax evasion via a mechanism that allowed them to cash out options without incurring tax liability for up to 30 years. This case illustrates that the media can conduct independent inquiry into tax avoidance activity.

Many firms claim that they are transparent in their corporate values; however, Paine et al. (2005) document that most corporate codes of conduct rarely discuss tax obligations.

As discussed in Dyck et al. (2010), even though journalists might be less specialized, they benefit from revealing complex issues, because high profile stories might help establish their career and reputation.

The discussion in this and the following paragraph is largely based on Houston el al. (2011).

Djankov et al. (2003) also provide data for the market share of circulation of private newspapers. In our sample, all countries (except the Philippines) have a market share of 100 %. We therefore do not use this variable because of its lack of variation.

Industry competition is commonly measured based on the market concentration ratio. Following Houston et al. (2011), we define the media industry as less competitive if the aggregate market share of the top five largest television stations or daily newspapers is high. Conversely, we define the media industry as more competitive if the aggregate market share of the non-top five largest television stations or daily newspapers is high.

We do not compute this measure over longer windows, such as five-year or ten-year windows (e.g., Dyreng et al. 2008), to avoid limiting our sample size. As noted by Dyreng et al. (2008), tax avoidance measures that are estimated over shorter periods of time may be imperfect because they include payments to (and refunds from) the tax authorities upon settling of tax disputes that arose years ago. Tax avoidance measures that are estimated over longer periods mitigate this concern because the income to which these taxes relate will more likely be included in the same ratio as the taxes. As a sensitivity check, we use a longer horizon of five years to compute tax avoidance, and find qualitatively unchanged results (untabulated). We also use two other alternate proxies of corporate tax avoidance. First, we compute tax avoidance based on the difference between the taxes on pre-tax income computed at the home-country statutory corporate tax rate and the tax expense recognized instead of the taxes actually paid. This measure is more closely related to the concept of GAAP effective tax rate, because it measures tax avoidance based on tax expense recognized in the financial statements rather than on cash tax actually paid. To capture the alternate measure of tax aggressiveness, we use an indicator variable that equals one if the country-industry tax avoidance based on tax expense recognized is within the top quartile, and zero otherwise (TAXAGGR_ALT). Second, we use the continuous measure of tax avoidance as the dependent variable. Our untabulated results are robust with these two alternate proxies of tax measures.

Other measures of tax avoidance used in the extant literature include DTAX (Frank et al. 2009), tax shelter prediction score (Wilson 2009), and unrecognized tax benefit (UTB) prediction score (Rego and Wilson 2012). However, because we use an international sample of firms from Compustat Global, many of the variables required to compute these measures of tax avoidance are either not available or not applicable in a setting outside the U.S. (e.g., tax shelter prediction score and UTB prediction score).

Industries are defined following the classification in Frankel et al. (2002), which is based on the following SIC codes: agriculture (0100–0999), mining and construction (1000–1999, excluding 1300–1399), food (2000–2111), textiles and printing/publishing (2200–2799), chemicals (2800–2824, 2840–2899), pharmaceuticals (2830–2836), extractive (2900–2999, 1300–1399), durable manufacturers (3000–3999, excluding 3570–3579 and 3670–3679), transportation (4000–4899), utilities (4900–4999), retail (5000–5999), services (7000–8999, excluding 7370–7379), and computers (3570–3579, 3670–3679, 7370–7379).

We control for the statutory tax rate to avoid the potential mechanical relation that may result from the tax avoidance measure computation including the statutory tax rate.

We hand-collect each country’s annual statutory corporate tax rate and whether the tax system is worldwide or territorial from various sources, including Ernst and Young’s Worldwide Corporate Tax Guide, KPMG’s Corporate and Indirect Tax Rate Survey, PwC’s Worldwide Tax Summaries, and PwC’s “Evolution of Territorial Tax Systems in the OECD” report.

We use an indicator variable rather than the ratio of foreign pre-tax income to total pre-tax income to proxy for multinational operations because Compustat Global does not provide a breakdown of domestic and foreign pre-tax income for non-U.S. multinationals. We recognize that a firm’s inclination to be tax aggressive may be influenced not only by local media coverage of tax avoidance, but also by foreign media coverage. In an additional robustness test, we repeat our analyses after excluding multinational firms (i.e., MULTI = 1) from our sample and the untabulated results indicate that our inferences remain unchanged.

Including higher order interaction terms in the model may cause the coefficient on the main effect of the conditioning variable to change sign unexpectedly, because the inclusion of MEDIA and its interaction with the conditioning factor can introduce multicollinearity among the interaction terms. To alleviate this concern, we mean-center MEDIA and the conditioning variables in our regression analyses (Aiken and West 1991; Neter et al. 1989).

Ai and Norton (2003) argue that the interaction effect in a non-linear model, such as the logistic specification of Eq. (3), cannot be evaluated and interpreted simply by looking at the sign, magnitude, and statistical significance of the coefficient on the interaction term. Rather, interpreting the interaction effect requires computation of modified statistics based on cross-derivatives or cross-differences. However, Greene (2010) contends that the modified statistics proposed by Ai and Norton (2003) do not provide meaningful interpretations and statistical inferences. In addition, Kolasinski and Siegel (2010) draw on the extant statistics literature (e.g., Le 1998) and show that the interaction coefficient and test statistic in a standard logistic specification are appropriate for research dealing with non-extreme probabilities and are economically meaningful. Therefore, we continue to estimate and interpret the interaction effects in Eq. (3).

Our sample period ends in 2007 because we obtain the requisite data from the Legacy Global Compustat database. The last year for which data are available in this database is 2007. The new Global Compustat database, which has the more recent data, does not include pre-tax exceptional items (data item 57 in the old database) and foreign income taxes (data item 51 in the old database). Therefore, we are unable to compute the variable TAXAVOID, which requires data item 57 as an input and the variable BTAXC, which requires data item 51 as an input, using the new Global Compustat database.

Our results are robust when these three countries are included in the sample.

In a robustness test, we employ weighted least squares to control for variation in sample country composition and re-estimate our models by country-year, so that each country-year observation receives equal weight in the regression (see “Additional Robustness Checks” section).

Our results are similar when we use an alternative proxy for democracy based on a democracy index obtained from the Polity IV dataset of Marshall and Jaggers (2007). This index is derived from coding the competitiveness of political participation, the openness and competitiveness of executive recruitment, and constraints on the executive, with higher values representing a more democratic environment. We do not include both proxies as instruments because both variables are very highly positively correlated (ρ = 0.83).

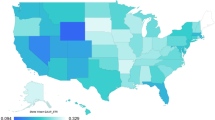

In this test, we compute the average country-year tax aggressiveness based on the continuous measure of tax avoidance, TAXAVOID.

We also conduct two additional robustness checks. First, we control for country-industry fixed effects in the regression. Second, we employ Fama–MacBeth (1973) estimation method based on yearly regression. Our untabulated results indicate that the coefficient on Comp_TV and Comp_Press is still negative and significant at the 1 % level; however, Private_TV is now insignificant. Overall these additional tests suggest that media competition, rather than media ownership has a more pronounced effect on tax aggressiveness.

We do not use these governance variables in our main regression because complete data is only available for 24 countries.

References

Ai, C., & Norton, E. C. (2003). Interaction terms in logit and probit models. Economics Letters, 80(1), 123–129.

Aiken, L., & West, S. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Ajinkya, B., Bhojraj, S., & Sengupta, P. (2005). The association between outside directors, institutional investors, and the properties of management earnings forecasts. Journal of Accounting Research, 43, 343–376.

Alm, J., & Torgler, B. (2011). Do ethics matter? Tax compliance and morality. Journal of Business Ethics, 101, 635–651.

Armstrong, C. S., Blouin, J. L., & Larcker, D. F. (2012). The incentives for tax planning. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 53, 391–411.

Atwood, T. J., Drake, M. S., & Myers, L. A. (2010). Book-tax conformity, earnings persistence and the association between earnings and cash flows. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 50, 111–125.

Atwood, T. J., Drake, M. S., Myers, J. N., & Myers, L. A. (2012). Home country tax system characteristics and corporate tax avoidance: International evidence. The Accounting Review, 87(6), 1831–1860.

Austin, C. R., & Wilson, R. (2015). Are reputational costs a determinant of tax avoidance? Working paper, University of Iowa.

Bankman, J. (2004). An academic’s view of the tax shelter battle. In H. J. Aaron & J. Slemrod (Eds.), The crisis in tax administration (pp. 9–37). Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

Bednar, M. (2012). Watchdog or lapdog? A behavioral view of the media as a corporate governance mechanism. Academy of Management Journal, 55(1), 131–150.

Bednar, M., Boivie, S., & Prince, N. (2013). Burr under the saddle: How media coverage influences strategic change. Organization Science, 24(3), 910–925.

Besley, T., Burgess, R., & Prat, A. (2002). Mass media and political accountability. In R. Islam (Ed.), The right to tell: The role of the media in development. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Besley, T., & Prat, A. (2006). Handcuffs for the grabbing hand? Media capture and government accountability. American Economic Review, 96, 720–736.

Boone, A., & White, J. (2015). The effect of institutional ownership on firm transparency and information production. Journal of Financial Economics, 117, 508–533.

Brunetti, A., & Weder, B. (2003). A free press is bad news for corruption. Journal of Public Economics, 87, 1801–1824.

Bryan, S., Nash, R., & Patel, A. (2010). How the legal system affects the equity mix in executive compensation. Financial Management, 39(1), 393–418.

Chen, P. F., He, S., Ma, Z., & Novoselov, K. E. (2013). Independent media and audit quality. The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, Working Paper.

Christensen, J. (2011). The looting continues: Tax havens and corruption. Critical Perspectives on International Business, 7(2), 177–196.

Christensen, J., & Murphy, R. (2004). The social irresponsibility of corporate tax avoidance: Taking CSR to the bottom line. Development, 47, 37–44.

Coronel, S. S. (2010). Corruption and the watchdog role of the news media. In P. Norris (Ed.), Public sentinel: News media and governance reform. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Dittmar, A., Mahrt-Smith, J., & Servaes, H. (2003). International corporate governance and corporate cash holdings. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 38, 111–133.

Djankov, S., McLiesh, C., Nenova, T., & Shleifer, A. (2003). Who owns the media? Journal of Law and Economics, 46, 341–381.

Dowling, G. R. (2014). The curious case of corporate tax avoidance: Is it socially irresponsible? Journal of Business Ethics, 124, 173–184.

Drucker, J. (2010, October 21). Google 2.4 % rate shows how $60 billion is lost to tax loopholes. Bloomberg.

Drucker, J. (2011, October 13). IRS auditing how Google shifted profits offshore to avoid taxes. Bloomberg.

Dyck, A., Morse, A., & Zingales, L. (2010). Who blows the whistle on corporate fraud? The Journal of Finance, 65(6), 2213–2253.

Dyreng, S., Hanlon, M., & Maydew, E. (2008). Long-run corporate tax avoidance. The Accounting Review, 83, 61–82.

Elster, J. (1989). Social norms and economic theory. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 3(4), 99–117.

EY. (2014). Bridging the divide: Highlights from 2014 tax risk and controversy survey.

Ferreira, M., Massa, M., & Pedro, P. (2010). Dividend clienteles around the world: Evidence from institutional holdings. Working Paper, Universidade Nova de Lisboa. http://ssrn.com/abstract=1447573.

Frank, M., Lynch, L., & Rego, S. (2009). Tax reporting aggressiveness and its relation to aggressive financial reporting. The Accounting Review, 84, 467–496.

Frankel, R. M., Johnson, M. F., & Nelson, K. K. (2002). The relation between auditors’ fees for non-audit services and earnings management. The Accounting Review, 77(Supplement), 71–106.

Gallemore, J., Maydew, E. L., & Thornock, J. R. (2014). The reputational costs of tax avoidance. Contemporary Accounting Research, 31(4), 1103–1133.

Gentzkow, M., & Shapiro, J. (2006). Media bias and reputation. Journal of Political Economy, 114, 280–316.

Goh, B. W., Lee, J., Lim, C. Y., & Shevlin, T. (2015). The effect of corporate tax avoidance on the cost of equity. The Accounting Review. doi:10.2308/accr-51432.

Graham, J. R., Hanlon, M., Shevlin, T., & Shroff, N. (2014). Incentives for tax planning and avoidance: Evidence from the field. The Accounting Review, 89(3), 991–1023.

Graham, J., & Tucker, A. (2006). Tax shelters and corporate debt policy. Journal of Financial Economics, 81, 563–594.

Greene, W. (2010). Testing hypotheses about interaction terms in nonlinear models. Economics Letters, 107(2), 291–296.

Hanlon, M. (2003). What can we infer about a firm’s taxable income from its financial statements? National Tax Journal, 56(4), 831–863.

Hanlon, M., & Heitzman, S. (2010). A review of tax research. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 50, 127–178.

Hanlon, M., & Slemrod, J. (2009). What does tax aggressiveness signal? Evidence from stock price reactions to news about tax shelter involvement. Journal of Public Economics, 93, 126–141.

Hardeck, I., & Hertl, R. (2014). Consumer reactions to corporate tax strategies: Effects on corporate reputation and purchasing behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 123, 309–326.

Houston, J. F., Lin, C., & Ma, Y. (2011). Media ownership, concentration and corruption in bank lending. Journal of Financial Economics, 100, 326–350.

Kanagaretnam, K., Lee, J., Lim, C. Y., & Lobo, G. J. (2015). Relation between auditor quality and corporate tax aggressiveness: Implications of cross-country institutional differences. Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory. doi:10.2308/ajpt-51417.

Kaufman, A. (2014, August 7). How Americans scared Walgreens out of a $4 billion tax dodge. Huffington Post.

Kim, J. B., Li, L., Wei, M., & Zhang, H. (2015). Captured media and corporate transparency: Evidence from international and Chinese firms. Working Paper. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2669910.

Kolasinski, A. C., & Siegel, A. F. (2010). On the economic meaning of interaction term coefficients in non-linear binary response regression models. Working Paper, University of Washington. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1668750.

La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., & Shleifer, A. (1999). Corporate ownership around the world. Journal of Finance, 54(2), 471–517.

La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. (1998). Law and finance. Journal of Political Economy, 106, 1113–1155.

Lanis, R., & Richardson, G. (2011). The effect of board of director composition on corporate tax aggressiveness. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 30, 50–70.

Lanis, R., & Richardson, G. (2014). Is corporate social responsibility performance associated with tax avoidance? Journal of Business Ethics, 124, 1–19.

Le, C. T. (1998). Applied categorical data analysis. New York: Wiley.

Leeson, P. (2008). Media freedom, political knowledge, and participation. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 22, 155–169.

Marshall, M., & Jaggers, K. (2007). Political regime characteristics and transitions, 1800–2007. Working Paper, George Mason University.

Mauro, P. (1995). Corruption and growth. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 110, 681–712.

Mehafdi, M. (2000). The ethics of international transfer pricing. Journal of Business Ethics, 28, 365–381.

Miller, G. (2006). The press as a watchdog for accounting fraud. Journal of Accounting Research, 44, 1001–1033.

Neter, J., Wasserman, W., & Kutner, M. H. (1989). Applied linear regression models (2nd ed.). Homewood, IL: Irwin.

Paine, L., Deshpande, R., Margolis, J. D., & Bettcher, E. (2005). Up to code: Does your company’s conduct meet world-class standards? Harvard Business Review, 83(12), 122–133.

Petersen, M. A. (2009). Estimating standard errors in finance panel data sets: Comparing approaches. Review of Financial Studies, 22, 435–480.

Pevzner, M., Xie, F., & Xin, X. (2015). When firms talk, do investors listen? The role of trust in stock market reactions to corporate earnings announcements. Journal of Financial Economics, 117(1), 190–223.

Preuss, L. (2012). Responsibility in paradise? The adoption of CSR tools by companies domiciled in tax havens. Journal of Business Ethics, 110, 1–14.

PwC. (2014). 17th Annual global CEO survey: Tax strategy, corporate reputation, and a changing international tax system.

Rego, S., & Wilson, R. (2012). Equity risk incentives and corporate tax aggressiveness. Journal of Accounting Research, 50(3), 775–809.

Reuters. (2012, December 6). Special Report: Amazon’s billion-dollar tax shield. Available at http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/12/06/us-tax-amazon-idUSBRE8B50AR20121206.

Richardson, G. (2006). Determinants of tax evasion: A cross-country investigation. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation, 15, 150–169.

Richardson, G. (2008). The relationship between culture and tax evasion across countries: Additional evidence and extensions. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation, 17, 67–78.

Richardson, S., Sloan, R., Soliman, M., & Tuna, I. (2005). Accrual quality, earnings persistence and stock prices. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 39(3), 437–485.

Scholes, M., Wolfson, M., Erickson, M., Hanlon, M., Maydew, E., & Shevlin, T. (2014). Taxes and business strategy: A planning approach (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Wilson, R. (2009). An examination of corporate tax shelter participants. The Accounting Review, 84, 969–999.

World Bank Institute. (2002). The right to tell: The role of mass media in economic development. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Acknowledgments

We thank Travis Chow, Amin Mawani, Sugata Roychowdhury and seminar participants at York University and the 2015 American Accounting Association Annual meeting for their helpful suggestions. Kanagaretnam and Lobo thank the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) for financial support. Lee and Lim thank the School of Accountancy Research Center (SOAR) at Singapore Management University for financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Variables Definition

Appendix: Variables Definition

TAXAVOID | Measure of tax avoidance, defined as: \(\frac{{\left[ {\sum\nolimits_{t - 2}^{t} {(PTEBX \times \tau )_{it} } - \sum\nolimits_{t - 2}^{t} C TP_{it} } \right]}}{{\sum\nolimits_{t - 2}^{t} P TEBX_{it} }},\) where PTEBX is pre-tax earnings before exceptional items, τ is home-country statutory corporate tax rate, and CTP is current taxes paid. The extent of tax avoidance is increasing in this measure |

TAXAGGR | An indicator variable that equals one if TAXAVOID (defined above) is within the top quartile in each country-industry combination, and zero otherwise. This variable captures tax aggressiveness |

Private_TV | Private TV ownership (by market share), computed as one minus state ownership of TV. Data from Djankov et al. (2003) |

Comp_TV | Competitiveness in the TV industry, measured as one minus the aggregate market share of the five largest television stations. Data from Djankov et al. (2003) |

Comp_Press | Competitiveness in the press industry measured as one minus the aggregate market share of the five largest daily newspapers. Data from Djankov et al. (2003) |

LEGAL | Law enforcement index, which is the mean score of the following three legal enforcement variables reported in La Porta et al. (1998): (1) the mean for 1980–1983 of a variable provided by Business International Corp., capturing the efficiency and integrity of the judicial system; (2) the mean for 1982–1995 of a rule of law variable obtained from International Country Risk; and (3) the mean for 1982–1995 of a corruption variable that assesses the corruption in government, obtained from International Country Risk |

INFOENV | Average country-level total institutional ownership divided by market capitalization in 2007, as reported in Ferreira et al. (2010) |

TAXRATE | Country statutory tax rate |

WW | An indicator that equals one if the home-country adopts a worldwide tax system, and zero if the home-country adopts a territorial tax system |

BTAXC | Proxy for the level of required book-tax conformity, following Atwood et al. (2010). BTAXC is computed based on the conditional variance of current tax expense from the following model, estimated by country-year: \(CTE_{t} = \theta_{0} + \theta_{1} PTBI_{t} + \theta_{2} ForPTBI_{t} + \theta_{3} DIV_{t} + e_{t},\) where CTE is current tax expense, PTBI is pre-tax book income, ForPTBI is the estimated foreign pre-tax book income, DIV is total dividends, and all variables are scaled by average total assets. BTAXC is then computed as the scaled ranking of the root mean-squared errors (RMSE) from these country-year regressions, and RMSEs are ranked in descending order so that higher values of BTAXC indicate higher required book-tax conformity |

TAXENF | Proxy for the level of tax enforcement in the country, based on the 1996 World Competitiveness Report |

VARCOMP | The sum of the value of option compensation and restricted stock compensation divided by total compensation at the country-level, to proxy for CEO incentives. Data is from Bryan et al. (2010) |

EARNVOL | The scaled descending rank, between zero and one, of cross-sectional pre-tax earnings volatility by country-year, following Atwood et al. (2012). Pre-tax earnings are defined as pre-tax income before exceptional items, divided by lagged total assets |

FACTOR | The first principal component from the factor analysis of the country’s legal tradition (common law versus code law), strength of investor rights, and ownership concentration as developed by La Porta et al. (1998) |

CULTURE | Ethnolinguistic fractionalization index that measures the probability that two randomly selected individuals within a country belong to the same ethnic group. It is an index between 0 and 1, with higher values denoting lower fractionalization. Data from Mauro (1995) and used in Richardson (2006) |

GDP | Log of Real historical Gross Domestic Product per capita (in billions of 2005 dollars). Source: www.ers.usda.gov/datafiles/International_Macroeconomic_Data/…Data |

TREND | Time trend variable, defined as the current fiscal year minus the first fiscal year in our sample (1995) |

PROA | Pre-tax return on assets is defined as pre-tax income before exceptional items, divided by lagged total assets |

SIZE | Natural logarithm of total assets |

R&D | Research and development expenditures divided by ending total assets |

LEV | Total liabilities divided by ending total assets |

GROWTH | One-year percentage change in sales |

MULTI | An indicator variable that equals zero if foreign income taxes is missing or zero, and equals one otherwise |

BIGN | Indicator variable that equals one if the firm’s auditor is a Big N auditor, and zero otherwise |

Democracy | Political rights index published by the Freedom House. Higher ratings indicate countries that comes closer “to the ideals suggested by the checklist questions of: (1) free and fair election; (2) those elected rule; (3) there are competitive parties or other competitive political groupings; (4) the opposition has an important role and power; and (5) the entities have self-determination or an extremely high degree of autonomy |

Education | This is a three level (upper, middle, and low) index relating to the highest education level attained, recoded and reported in WVS. We code the variable as 1 if the highest education level attained is upper or middle, and 0 otherwise, and use the average education level in each country to proxy for the general education level of the population |

ΔWC | Change in current operating assets minus current operating liabilities from year t − 1 to year t, divided by total assets |

ΔNCO | Change in noncurrent operating assets minus noncurrent operating liabilities from year t − 1 to year t, divided by total assets |

ΔFIN | Change in financial assets minus financial liabilities from year t − 1 to year t, divided by total assets |

Free_Broadcast | Broadcast freedom index defined as one minus the Broadcast Freedom Index from Freedom House in the year 2000. The index ranges from 0 to 15 and measures the extent of laws and regulations that influence broadcast content. The greater the index, the higher is the broadcast freedom |

Free_Print | Print freedom index defined as one minus the Print Freedom Index from Freedom House in the year 2000. The index ranges from 0 to 15, which measures the extent of laws and regulations that influence print content. The greater the index, the higher is the print freedom |

TAXAGGR_ALT | Alternative measure of tax avoidance, defined as \(\frac{{\left[ {\sum\nolimits_{t - 2}^{t} {(PTEBX \times \tau )_{it} } - \sum\nolimits_{t - 2}^{t} C TE_{it} } \right]}}{{\sum\nolimits_{t - 2}^{t} P TEBX_{it} }},\) where PTEBX is pre-tax earnings before exceptional items, τ is home-country statutory corporate tax rate, and CTE is current tax expense. It is an indicator that equals one if the above measure is within the top quartile in each country-industry combination, and zero otherwise |

FAMILY | Percent of firms controlled by the family shareholder in each country, where the cutoff used to define effective control is 10 %. Data from La Porta et al. (1999) |

WIDELYHEL:D | Percent of firms without any effective controlling shareholders in each country, where the cutoff used to define effective control is 10 %. Data from La Porta et al. (1999) |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kanagaretnam, K., Lee, J., Lim, C.Y. et al. Cross-Country Evidence on the Role of Independent Media in Constraining Corporate Tax Aggressiveness. J Bus Ethics 150, 879–902 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3168-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3168-9