Abstract

Purpose

We determined whether racial/ethnic differences in patient experiences with care influence timeliness and type of initial surgical breast cancer treatment for a sample of female Medicare cancer patients.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using the linked Epidemiology and End Results-Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (SEER-CAHPS) dataset. The outcomes were: (1) time-to-initial surgical treatment, and (2) type of treatment [breast conserving surgery (BCS) vs. mastectomy]. The indicators were reports of four types of patient experiences with care including doctor communication, getting care quickly, getting needed care, and getting needed Rx. Interaction terms in each multivariable logistic model examined if the associations varied by race/ethnicity.

Results

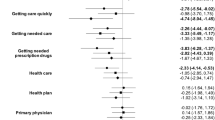

Of the 2069 patients, 84.6% were White, 7.6% Black and 7.8% Hispanic. After adjusting for potential confounders, non-Hispanic Black patients who provided excellent reports of their ability to get needed prescriptions had lower odds of receiving surgery within 2-months of diagnosis, compared to NH-Whites who provided less than excellent reports (aOR: 0.29, 95% CI 0.09–0.98). There were no differences based on 1-month or 3-month thresholds. We found no other statistically significant effect of race/ethnicity. As to type of surgery, among NH Blacks, excellent reports of getting care quickly were associated with higher odds of receiving BCS versus mastectomy (aOR: 2.82, 95% CI 1.16–6.85) compared to NH Whites with less than excellent reports. We found no other statistically significant differences by race/ethnicity.

Conclusion

Experiences with care are measurable and modifiable factors that can be used to assess and improve aspects of patient-centered care. Improvements in patient care experiences of older adults with cancer, particularly among minorities, may help to eliminate racial/ethnic disparities in timeliness and type of surgical treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Codes are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. SEER-CAHPS linked dataset used for this manuscript is publicly available through the National Cancer Institute, Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences.

Abbreviations

- US :

-

United States

- BCS :

-

Breast conserving surgery

- SEER-CAHPS :

-

Surveillance, epidemiology, and end results—consumer assessment of healthcare providers and systems

- NCI :

-

National Cancer Institute

- SEER :

-

Surveillance, epidemiology, and end results

- CMS :

-

Centers for medicare and medicaid services

- CAHPS :

-

Medicare consumer assessment of healthcare providers and systems

- FFS :

-

Fee for service

- ANOVA :

-

Analysis of variance

References

United States Cancer Statistics Working Group (2020) “U.S. Cancer Statistics Data Visualizations Tool, based on 2019 submission data (1999–2017).” United States Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute. www.cdc.gov/cancer/dataviz. Released in June 2020. Accessed June, 2020

American Cancer Society (2019) “Breast Cancer Facts and Figures 2019–2020, ” American Cancer Society, Atlanta, 2019. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/breast-cancer-facts-and-figures/breast-cancer-facts-and-figures-2019-2020.pdf

Moo TA, Sanford R, Dang C, Morrow M (2018) Overview of breast cancer therapy. PET Clin 13(3):339–354

Halpern M, Holden D (2012) Disparities in timeliness of care for US Medicare patients diagnosed with cancer. Curr Oncol 19(6):e404

Wright GP, Wong JH, Morgan JW, Roy-Chowdhury S, Kazanjian K, Lum SS (2010) Time from diagnosis to surgical treatment of breast cancer: factors influencing delays in initiating treatment. Am Surg 76(10):1119–1122

Bleicher RJ et al (2016) “Time to surgery and breast cancer survival in the United States,” (in eng). JAMA Oncol 2(3):330–339. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.4508

Padilla-Ruiz M et al (2020) Factors that influence treatment delay for patients with breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 28:1–8

Ho PJ, Cook AR, Binte NK, Ri M, Liu J, Li J, Hartman M (2020) Impact of delayed treatment in women diagnosed with breast cancer: a population-based study. Cancer Med 9(7):2435–2444

Richards M, Westcombe A, Love S, Littlejohns P, Ramirez A (1999) Influence of delay on survival in patients with breast cancer: a systematic review. The Lancet 353(9159):1119–1126

Fisher B et al (2002) Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized trial comparing total mastectomy, lumpectomy, and lumpectomy plus irradiation for the treatment of invasive breast cancer. N Engl J Med 347(16):1233–1241

Hawley ST et al (2009) Decision involvement and receipt of mastectomy among racially and ethnically diverse breast cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst 101(19):1337–1347

Morrow M et al (2009) Surgeon recommendations and receipt of mastectomy for treatment of breast cancer. JAMA 302(14):1551–1556

Katz SJ et al (2005) Patient involvement in surgery treatment decisions for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 23(24):5526–5533

Silber JH et al (2013) Characteristics associated with differences in survival among black and white women with breast cancer. JAMA 310(4):389–397

Sheppard VB et al (2015) Disparities in breast cancer surgery delay: the lingering effect of race. Ann Surg Oncol 22(9):2902–2911

Mandelblatt J et al (2005) “Breast cancer prevention in community clinics: will low-income Latina patients participate in clinical trials?” (in eng). Prev Med 40(6):611–618. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.09.004

Morris CR, Cohen R, Schlag R, Wright WE (2000) Increasing trends in the use of breast-conserving surgery in California. Am J Public Health 90(2):281

Anhang Price R et al (2014) “Examining the role of patient experience surveys in measuring health care quality” (in eng). Med Care Res Rev 71(5):522–554. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558714541480

Farias AJ, Ochoa CY, Toledo G, Bang SI, Hamilton AS, Du XL (2020) “Racial/ethnic differences in patient experiences with health care in association with earlier stage at breast cancer diagnosis: findings from the SEER-CAHPS data” (in eng). Cancer Causes Control 31(1):13–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-019-01254-3

Farias AJ, Toledo G, Ochoa CY, Hamilton AS (2021) Racial/ethnic disparities in patient experiences with health care in association with earlier stage at colorectal cancer diagnosis: findings from the SEER-CAHPS data. Med Care 59(4):295–303

Mollica MA et al (2017) “Examining colorectal cancer survivors’ surveillance patterns and experiences of care: a SEER-CAHPS study” (in eng). Cancer Causes Control 28(10):1133–1141. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-017-0947-2

Chawla N et al (2015) “Unveiling SEER-CAHPS®: a new data resource for quality of care research” (in eng). J Gen Intern Med 30(5):641–650. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-014-3162-9

National Cancer Institute. “Surgery Codes Breast.” https://seer.cancer.gov/archive/manuals/2011/Surgery_Codes_Breast_09272011.pdf. Accessed Oct 2020

National Cancer Institute. “Guidance on analytic approaches when modeling items and composites in analyses using SEER-CAHPS data”. https://healthcaredelivery.cancer.gov/seer-cahps/researchers/approaches_guidance.html. Accessed 19 Oct 2019

Lines LM, Cohen J, Halpern MT, Smith AW, Kent EE (2019) “Care experiences among dually enrolled older adults with cancer: SEER-CAHPS, 2005–2013” (in eng). Cancer Causes Control 30(10):1137–1144. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-019-01218-7

Halpern MT, Urato MP, Kent EE (2017) “The health care experience of patients with cancer during the last year of life: analysis of the SEER-CAHPS data set” (in eng). Cancer 123(2):336–344. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.30319

Wilson RT et al (2007) Disparities in breast cancer treatment among American Indian, Hispanic and non-Hispanic white women enrolled in Medicare. J Health Care Poor Underserved 18(3):648–664

Stata Statistical Software (2019) StataCorp LP., College Station, TX

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. “Six Domains of Health Care Quality.” https://www.ahrq.gov/talkingquality/measures/six-domains.html

Smith EC, Ziogas A, Anton-Culver H (2013) Delay in surgical treatment and survival after breast cancer diagnosis in young women by race/ethnicity. JAMA Surg 148(6):516–523

Selove R et al (2016) Time from screening mammography to biopsy and from biopsy to breast cancer treatment among Black and White, women Medicare beneficiaries not participating in a health maintenance organization. Womens Health Issues 26(6):642–647

Gorin SS, Heck JE, Cheng B, Smith SJ (2006) “Delays in breast cancer diagnosis and treatment by racial/ethnic group” (in eng). Arch Intern Med 166(20):2244–2252. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.20.2244

Ochoa CY, Toledo G, Iyawe-Parsons A, Navarro S, Farias AJ (2021) Multilevel influences on black cancer patient experiences with care: a qualitative analysis. JCO Oncol Pract 17(5):e645–e653

Cuevas AG, O’Brien K, Saha S (2016) African American experiences in healthcare: “I always feel like I’m getting skipped over.” Health Psychol 35(9):987

Bellavance EC, Kesmodel SB (2016) Decision-making in the surgical treatment of breast cancer: factors influencing women’s choices for mastectomy and breast conserving surgery. Front Oncol 6:74

Gu J, Groot G, Boden C, Busch A, Holtslander L, Lim H (2018) Review of factors influencing women’s choice of mastectomy versus breast conserving therapy in early stage breast cancer: a systematic review. Clin Breast Cancer 18(4):e539–e554

Mohan CS et al (2020) The association between patient experience and healthcare outcomes using SEER-CAHPS patient experience and outcomes among cancer survivors. J Geriatr Oncol 12:623–631

Anhang Price R et al (2022) A systematic review of strategies to enhance response rates and representativeness of patient experience surveys. Med Care 60(12):910

Klein DJ et al (2011) Understanding nonresponse to the 2007 medicare CAHPS survey. Gerontologist 51(6):843–855. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnr046

Acknowledgements

This study used the linked SEER-CAHPS data resource. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the sole responsibility of the authors. The authors acknowledge the efforts of the National Cancer Institute; the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; Information Management Services (IMS), Inc.; and the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program tumor registries in the creation of the SEER-CAHPS data resource.

Funding

Efforts by Mariana Arevalo, PhD, MSPH were supported by a pre-doctoral fellowship at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, School of Public Health, Susan G. Komen Traineeship in Breast Cancer Disparities (GTDR14300827). SEER-CAHPS data were procured by Albert J. Farias, PhD with support from a University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston School of Public Health Cancer Education and Career Development Program grant from the National Cancer Institute (R25-CA57712). Efforts by Trevor A. Pickering, PhD, MS were supported by grants UL1TR001855 and UL1TR000130 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS) of the U.S. National Institutes of Health. The contents of this manuscript are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the funding bodies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MA, AJF, and SWV contributed to the conception and design of this study. TAP contributed to data management. MA, AJF, and SWV contributed to the analyses and interpretation of data. MA prepared the first draft of this manuscript with feedback from AJF. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical approval

The study was reviewed and granted exempt status by the UTHealth Committee for Protection of Human Subjects (HSC-SPH-20–0812).

Patient consent to participate

This study used a large population-based dataset with unidentifiable patient information.

Consent to publish

N/A.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Arevalo, M., Pickering, T.A., Vernon, S.W. et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in the association between patient care experiences and receipt of initial surgical breast cancer care: findings from SEER-CAHPS. Breast Cancer Res Treat 203, 553–564 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-023-07148-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-023-07148-y