Abstract

Purpose

To characterize the distress trajectory in patients with newly diagnosed, non-metastatic breast cancer from pre-neoadjuvant chemotherapy until 12 months after onset of treatment and to identify demographic and clinical predictors of distress in these patients.

Methods

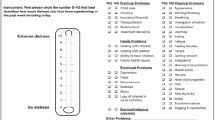

In a retrospective, longitudinal study, chart review data were abstracted for 252 eligible patients treated at a comprehensive cancer care center. The center screens for distress at least monthly with the distress thermometer; the highest distress score per month was included in the analyses. The growth trajectory was established using mixed modeling and predictors were added to the initial growth model in subsequent models.

Results

Distress showed a cubic growth trajectory with highest distress prior to treatment onset followed by a steep decline in the first three months of treatment. A slight increase in distress was apparent over months 6–10. Being Hispanic was associated with a stronger increase in distress in the second half of the year (p = 0.012). NACT was associated with lower distress and surgery with higher distress (both: p < 0.001).

Conclusion

Distress is at its peak prior to treatment onset and rapidly decreases once treatment has started. Oncologist should be aware that both completion of NACT and undergoing surgery are associated with increases in distress and Hispanic patients may be more at risk for an increase in distress at these times; this suggests that careful monitoring of distress during the treatment trajectory and in Hispanic patients in particular in order to provide timely support.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on reasonable request form the corresponding author.

References

National Comprehensive Cancer Network I. 2022. Distress Management. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology 2022.

Mehnert A, Hartung TJ, Friedrich M, Vehling S et al (2017) One in two cancer patients is significantly distressed: prevalence and indicators of distress. Psychooncology. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4464

Zabora J, BrintzenhofeSzoc K, Curbow B, Hooker C et al (2001) The prevalence of psychological distress by cancer site. Psychooncology 10(1):19–28. https://doi.org/10.1002/1099-1611(200101/02)10:1%3c19::AID-PON501%3e3.0.CO;2-6

Härtl K, Engel J, Herschbach P, Reinecker H et al (2010) Personality traits and psychosocial stress: quality of life over 2 years following breast cancer diagnosis and psychological impact factors. Psychooncology 19(2):160–169. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1536

Hegel MT, Moore CP, Collins ED, Kearing S et al (2006) Distress, psychiatric syndromes, and impairment of function in women with newly diagnosed breast cancer. Cancer 107(12):2924–2931. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.22335

Lutgendorf SK, Sood AK, Antoni MH (2010) Host factors and cancer progression: biobehavioral signaling pathways and interventions. J clin oncol 28(26):4094–4099. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.26.9357

Oh H-M, Son C-G (2021) The risk of psychological stress on cancer recurrence: a systematic review. Cancers 13(22):5816. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13225816

Groenvold M, Petersen MA, Idler E, Bjorner JB et al (2007) Psychological distress and fatigue predicted recurrence and survival in primary breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat 105(2):209–219. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-006-9447-x

Adeyemi OJ, Gill TL, Paul R, Huber LB (2021) Evaluating the association of self-reported psychological distress and self-rated health on survival times among women with breast cancer in the U.S. PLoS ONE 16(12):e0260481. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0260481

Antoni MH, Lechner SC, Kazi A, Wimberly SR et al (2006) How stress management improves quality of life after treatment for breast cancer. J Consult Clin Psychol 74(6):1143–1152. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006x.74.6.1152

Andersen BL, Yang H-C, Farrar WB, Golden-Kreutz DM et al (2008) Psychologic intervention improves survival for breast cancer patients: a randomized clinical trial. Cancer 113(12):3450–3458. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.23969

Yang H-C, Thornton LM, Shapiro CL, Andersen BL (2008) Surviving recurrence: psychological and quality-of-life recovery. Cancer 112(5):1178–1187. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.23272

Kant J, Czisch A, Schott S, Siewerdt-Werner D et al (2018) Identifying and predicting distinct distress trajectories following a breast cancer diagnosis—from treatment into early survival. J Psychosom Res 115:6–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2018.09.012

Renna ME, Shrout MR, Madison AA, Alfano CM et al (2020) Within-person changes in cancer-related distress predict breast cancer survivors’ inflammation across treatment. Psychoneuroendocrinology 121:104866. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2020.104866

Culver JL, Arena PL, Antoni MH, Carver CS (2002) Coping and distress among women under treatment for early stage breast cancer: comparing african americans, hispanics and non-hispanic whites. Psychooncology 11(6):495–504. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.615

Fayanju OM, Yenokyan K, Ren Y, Goldstein BA et al (2019) The effect of treatment on patient-reported distress after breast cancer diagnosis. Cancer 125(17):3040–3049. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.32174

Fayanju OM, Ren Y, Stashko I, Power S et al (2021) Patient-reported causes of distress predict disparities in time to evaluation and time to treatment after breast cancer diagnosis. Cancer 127(5):757–768. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.33310

Wittenberg L, Yutsis M, Taylor S, Giese-Davis J et al (2010) Marital status predicts change in distress and well-being in women newly diagnosed with breast cancer and their peer counselors. Breast J 16(5):481–489. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-4741.2010.00964.x

Mertz BG, Bistrup PE, Johansen C, Dalton SO et al (2012) Psychological distress among women with newly diagnosed breast cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs 16(4):439–443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2011.10.001

Politi MC, Enright TM, Weihs KL (2007) The effects of age and emotional acceptance on distress among breast cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 15(1):73–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-006-0098-6

Pirl WF, Fann JR, Greer JA, Braun I et al (2014) Recommendations for the implementation of distress screening programs in cancer centers: report from the American psychosocial oncology society (APOS), association of oncology social work (AOSW), and oncology nursing society (ons) joint task force. Cancer 120(19):2946–2954. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.28750

Ma X, Zhang J, Zhong W, Shu C et al (2014) The diagnostic role of a short screening tool–the distress thermometer: a meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer 22(7):1741–1755. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-014-2143-1

Ploos van Amstel FK, Tol J, Sessink KH, van der Graaf WTA et al (2017) A specific distress cutoff score shortly after breast cancer diagnosis. Cancer Nurs 40(3):E35-e40. https://doi.org/10.1097/ncc.0000000000000380

Corporation I. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows 1989. 2016 Armon, N.Y

Kuznetsova A, Brockhoff PB, Christensen RHB (2017) lmerTest package: tests in linear mixed effects models. J Stat Softw 82(13):1–26. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v082.i13

Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, Walker S (2015) Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Softw 67(1):1–48. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01

Wang J, Haiyi X, Fisher JH (2012) Application of multilevel modelling to longitudinal data, in Multilevel Models. Applications using SAS. Higher Eduction Press and Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co., Berlin

Helgeson VS, Snyder P, Seltman H (2004) Psychological and physical adjustment to breast cancer over 4 years: identifying distinct trajectories of change. Health Psychol 23(1):3

Assari S, Khoshpouri P, Chalian H (2019) Combined effects of race and socioeconomic status on cancer beliefs, cognitions, and emotions. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland) 7(1):17. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare7010017

Ashing-Giwa KT, Padilla G, Tejero J, Kraemer J et al (2004) Understanding the breast cancer experience of women: a qualitative study of African American, Asian American. Lat Cauc Cancer Surviv Psychooncology 13(6):408–428. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.750

Thomas EJ, Elliott R (2009) Brain imaging correlates of cognitive impairment in depression. Front Hum Neurosci. https://doi.org/10.3389/neuro.09.030.2009

Spencer SM, Lehman JM, Wynings C, Arena P et al (1999) Concerns about breast cancer and relations to psychosocial well-being in a multiethnic sample of early-stage patients. Health Psychol 18(2):159–168. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.18.2.159

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute under award number (Grant No. P30CA016672).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TL and DT contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation and data collection were performed by TL and ET. Analyses were performed by TL. The first draft of the manuscript was written by TL and ZK. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript and read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical approval

This observational study and a corresponding waiver for consent was approved by the institution’s Internal Review Board.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Lacourt, T.E., Koncz, Z., Tullos, E.A. et al. A detailed description of the distress trajectory from pre- to post-treatment in breast cancer patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat 197, 299–305 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-022-06805-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-022-06805-y