Abstract

The effect of a linear stratification in the free atmosphere on near-surface properties in a free convective boundary layer (CBL) is investigated by means of direct numerical simulation. We consider two regimes: a neutral stratification regime, which represents a CBL that grows into a residual layer, and a strong stratification regime, which represents the equilibrium (quasi-steady) entrainment regime. We find that the mean buoyancy varies as \(z^{-1/3}\), in agreement with classical similarity theory. However, the root-mean-square (r.m.s.) of the buoyancy fluctuation and the r.m.s. of the vertical velocity vary as \(z^{-0.45}\) and \(\ln z\), respectively, both in disagreement with theory. These scaling laws are independent of the stratification regime, but the depth over which they are valid depends on the stratification. In the strong stratification regime, this depth is about 20 to 25 % of the CBL depth instead of the commonly used 10 %, which we only observe under neutral conditions. In both regimes, the near-surface flow structure can be interpreted as a hierarchy of circulations attached to the surface. Based on this structure, we define a new near-surface layer in free convection, the plume-merging layer, that is conceptually different from the constant-flux layer. The varying depth of the plume-merging layer depending on the stratification accounts for the varying depth of validity of the scaling laws. These findings imply that the buoyancy transfer law needed in mixed-layer and single-column models is well described by the classical similarity theory, independent of the stratification in the free atmosphere, even though other near-surface properties, such as the r.m.s. of the buoyancy fluctuation and the r.m.s. of the vertical velocity, are inconsistent with that theory.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Free convection is the turbulence regime that prevails in the unstable planetary boundary layer (PBL) when strong surface heating coincides with weak mean horizontal flow. These conditions are primarily found near the centre of anticyclones (Wallace and Hobbs 2006). The properties and evolution of these systems are relevant to weather forecasting, as excess near-surface temperatures may occur (Miralles et al. 2014). However, our ability to model the temperature and other near-surface properties in these areas remains limited due to an incomplete understanding of the near-surface flow structure. We aim here to improve this understanding by means of direct numerical simulations.

Flux-profile relationships and transfer laws are key to realistically represent land-atmosphere interactions in atmospheric numerical models. Still, field measurements in the unstable PBL (see review in Zilitinkevich et al. 1998, 2006) and laboratory studies of Rayleigh–Bénard convection (see review in Du Puits et al. 2007; Mellado 2012; Ahlers et al. 2012) show that near-surface properties can deviate significantly from the predictions made according to the classical similarity theory (Prandtl 1932; Obukhov 1946; Priestley 1954).

The deviations from classical similarity theory are attributed to the formation of large-scale circulations, identified as flow structures that extend across the whole system and interact with the flow in the near-surface region (Kraichnan 1962; Businger 1973). This interaction invalidates the basic assumption made in classical similarity theory, namely, that the near-surface region is unaffected by the outer scales. Retaining this effect improves the theoretical predictions, both in the unstable PBL (see, e.g., Schumann 1988; Zilitinkevich et al. 1998, 2006) and in Rayleigh–Bénard convection (see, e.g., Grossmann and Lohse 2000; Chillà and Schumacher 2012).

The relevance of large-scale circulations inside the near-surface region raises the following question: how do near-surface properties, such as flux-profile relationships and transfer laws, depend on outer-layer properties that can modify the large-scale circulations? For instance, large-scale circulations can be modified by entrainment-zone properties (de Roode et al. 2004), while entrainment-zone properties can even influence near-surface properties directly (van de Boer et al. 2014). Here, we complement this previous work by investigating how near-surface properties depend on the stratification of the free atmosphere.

We study a free convective boundary layer (CBL) that forms over a flat, aerodynamically smooth surface and that grows into a fluid with a constant buoyancy gradient, \(N^2\). Convection is forced by a constant and homogeneous surface buoyancy flux, \(B_0\). The effect of a large-scale pressure gradient is not considered, and the mean wind velocity is set to zero. We compare two configurations: one with \(N^2=0\), which corresponds to a CBL penetrating into a neutrally stratified fluid, and one with \(N^2>0\), which corresponds to a CBL penetrating into a stably stratified fluid. In this second configuration, we focus on the equilibrium (quasi-steady) entrainment regime.

The first reason to consider these two configurations is that they enclose any atmospheric CBL growing into a linearly stratified free atmosphere over land. The first configuration represents a weak stratification regime, such as is established after the early morning transition when the CBL grows across the residual layer. The second configuration represents a strong stratification regime, such as can be found during the afternoon period. The second reason is that the large-scale circulations differ from one configuration to the other. This difference is induced by the capping inversion that forms at the CBL top when \(N^2>0\), which hampers the vertical motion of the fluid. Thus, by comparing these two configurations, we can study how different conditions far from the surface affect near-surface properties.

We compare our results with data corresponding to a CBL with an imposed capping inversion (e.g., de Roode et al. 2004; Sullivan and Patton 2011) and with data from Rayleigh–Bénard convection. In addition to the relevance that these two configurations also have in nature and engineering, the vertical motion in these two cases is restricted even more effectively than in our case, which yields different large-scale circulations, and thus, possibly, different near-surface properties.

We use direct numerical simulation (DNS) to remove the uncertainty associated with turbulence models near the surface (Sullivan et al. 1994; Moin and Mahesh 1998; Zilitinkevich et al. 1998; Brasseur and Wei 2010). Despite the moderate values of Reynolds number currently achieved with DNS, we start to observe a tendency towards Reynolds number similarity that allows certain extrapolation of the results to atmospheric conditions (Tennekes and Lumley 1972; Dimotakis 2000; Monin and Yaglom 2007). Moreover, we can assess the sensitivity of the results to changes in the Reynolds number, since the results are independent of the numerical algorithm and there is no turbulence-model uncertainty to be considered in the interpretation of the data.

We focus on the case of a flat surface and do not study the effect of roughness or larger-size surface heterogeneity. This idealized configuration corresponds, for instance, to an air-water interface when the air motion is weak enough for the interface to remain flat and aerodynamically smooth (Brutsaert 1982). The advantage of such a simple configuration is that it allows us to analyze in detail the flow near the surface. At the same time, despite the limited range of surface conditions covered by such a configuration, the study serves as a reference for, and provides insight into, the flow structure over aerodynamically rough surfaces.

2 Formulation

2.1 Governing Equations

We solve the Navier-Stokes equations in the Boussinesq approximation

where \(u_i\) is the velocity component in the direction \(\hat{\mathbf {e}}_i\), p is a modified pressure divided by the constant reference density, and b is the buoyancy. The parameter \(\nu \) is the kinematic viscosity, and \(\kappa \) is the molecular diffusivity. The operators \(\partial _t\) and \(\partial _j\) are the partial derivatives with respect to time, t, and with respect to the spatial coordinate \(x_j\), and \(\delta _{ij}\) is the Kronecker delta. Einstein summation convention applies to roman-letter indices throughout.

The background buoyancy varies as \(N^2z\), where \(z=x_3\) is the vertical distance from the surface. The buoyancy can be related to the virtual potential temperature \(\theta _v\) through the linear relation \(b = g(\theta _v-\theta _{v,0})/\theta _{v,0}\), where \(\theta _{v,0}\) is the reference value obtained by extrapolating the linear stratification of \(\theta _v\) in the free atmosphere downwards to the surface. As explained in the introduction and further discussed below, we consider two configurations: a neutrally stratified configuration, \(N^2=0\), and a stably stratified configuration, \(N^2>0\).

In the stably stratified configuration, linear relaxation terms act on the velocity and buoyancy fields inside a sponge layer occupying the upper 25 % of the computational domain. The reference values of these relaxation terms are \(\mathbf {u}_{\mathrm{ref}}=0\) and \(b_{\mathrm{ref}}=N^2z\), respectively. The proportionality coefficients of the relaxation terms increase quadratically with the distance from the inner limit of the sponge layer, from zero at the inner limit to \(N/2\pi \) at the outer limit.

No-penetration, no-slip boundary conditions are imposed at the bottom boundary of the computational domain, and no-penetration, free-slip boundary conditions are imposed at the top boundary. For the buoyancy field, we use Neumann boundary conditions to maintain constant buoyancy fluxes \(-\kappa N^2\hat{\mathbf {e}}_3\) and \(B_0\hat{\mathbf {e}}_3\) at the top and at the bottom, respectively. Periodicity applies at the lateral boundaries.

The initial velocity field is set to zero, while the initial buoyancy field is defined as

where \(b_{\mathrm{ics}}(x_1,x_2)=[(B_0-\kappa N^2)/\kappa ]\delta _{\mathrm{ics}}(x_1,x_2)\) is the surface buoyancy and \(\delta _{\mathrm{ics}}\) is the local gradient thickness. A broadband field is constructed by specifying \(\delta _{\mathrm{ics}}(x_1,x_2)=\delta _0[1+\xi (x_1,x_2)]\), the parameter \(\delta _0\) to be given. The random field \(\xi (x_1,x_2)\) has a Gaussian power spectral density centred at a spatial frequency \(\lambda _0^{-1}=(4\delta _0)^{-1}\) and with a standard deviation \((6\lambda _0)^{-1}\), so that there is practically no energy with spatial frequencies below \((2\lambda _0)^{-1}\). The phase of \(\xi \) is random, and its mean value is zero and the root-mean-square (r.m.s.) is \(\xi _{\mathrm{rms}}=0.1\).

2.2 Dimensional Analysis

The system is statistically homogeneous inside horizontal planes, and the statistical properties depend on the independent variables \(\{z,\,t\}\). We are interested in the fully-developed turbulent regime that is established after an initial transient, once the details of the initial condition have been sufficiently forgotten. The controlling parameters are then \(\{\nu ,\, \kappa ,\, B_0,\, N\}\), with the Prandtl number set equal to one, i.e., \(\nu /\kappa =1\). Choosing \(B_0\) and \(\kappa \) to non-dimensionalize the problem, statistical properties can be expressed as a function of the non-dimensional variables \(\{z/z_\kappa ,\,t/t_\kappa ;\,L_0/z_\kappa \}\). The dependence on a stratification strength \(N^2>0\) has been expressed in terms of the length scale

(this length scale is further explained below). Variables and parameters have been normalized with the inner (or surface) scales, and we consider an aerodynamically smooth surface, for which the inner length scale is

viz. the diffusive length scale (Townsend 1959; Fedorovich and Shapiro 2009). The corresponding velocity, buoyancy and time scales are

The outer length scale, \(z_*(t)\), is defined as

in the neutrally stratified case, and as

in the stably stratified cases, where

is the total buoyancy flux. Angle brackets indicate averaging inside the horizontal planes, while primes indicate turbulent fluctuations. Different definitions of the CBL depth, h, are commensurate with \(z_*\). For instance, in the stably stratified cases, the height of minimum mean buoyancy flux is \(1.17\,z_*\), and the height of maximum mean buoyancy gradient is \(1.27\,z_*\) (Garcia and Mellado 2014). In the neutrally stratified case, there exists no local minimum in the buoyancy flux, nor maximum in the buoyancy gradient, but \(z_*\) also provides a characteristic scale of outer-layer properties (Mellado 2012).

We demonstrate in Sect. 3 that, in terms of \(z_*\), the depth of the turbulent region becomes approximately equal in both the neutrally and the stably stratified configurations. Hence, by comparing these two configurations for a given value of \(z_*\), we can investigate how differences in the large-scale organisation of the flow affect the near-surface region.

Equation 6a provides a one-to-one mapping between \(z_*\) and t, so that statistical properties can be rewritten as a function of the non-dimensional variables \(\{z/z_\kappa ,\,z_*/z_\kappa ;\,z_*/L_0\}\). The reason for using the variable \(z_*/z_\kappa \) instead of \(t/t_\kappa \) in the analysis presented below is that the ratio \(z_*/z_\kappa \) measures the scale separation between the CBL depth and the surface length scale. Accordingly, we refer to this ratio as the scale-separation parameter, which can be related to a convective Reynolds number by

where

is the convective velocity scale (Deardorff 1970). Hence, by comparing cases with different values of \(z_*/z_\kappa \), we can assess the dependence of our results on the Reynolds number.

The variable \(z_*/L_0\) proves useful in the analysis of a CBL growing into a linearly stratified free atmosphere because it combines the dependence on \(\{t,\,B_0,\, N\}\) into a single parameter, without loss of generality. For instance, for a given surface buoyancy flux \(B_0=0.005\) m\(^2\) s\(^{-3}\), a CBL with a depth \(h=750\) m penetrating into a free atmosphere with a stratification \(N=0.015\) s\(^{-1}\) is equivalent to a CBL of depth \(h=1500\) m penetrating into a free atmosphere with a stratification \(N=0.0096\) s\(^{-1}\), since both cases correspond to \(z_*/L_0\approx 20\). By appropriately rescaling the variables, we can reproduce the statistical properties of one CBL from the data of the other CBL, without having to perform a second simulation. In other words, one single simulation is sufficient to study the dependence of our results on all possible combinations of the parameters \(B_0\) and N.

The length scale \(L_0\) can be interpreted as a cross-over CBL depth beyond which \(N^2>0\) influences the CBL dynamics (Garcia and Mellado 2014). Atmospheric midday values of \(z_*/L_0\) vary between 5 and 50, and the equilibrium (quasi-steady) entrainment regime sets in at \(z_*/L_0\approx \) 10–15. Within this quasi-steady regime, the integral time scale of the turbulent fluctuations is much shorter than the characteristic time associated with the evolution of the CBL depth, and some statistics of the flow behave self-similarly (Fedorovich et al. 2004). Hence, the two limits \(z_*/L_0\ll 1\) and \(z_*/L_0\gg 1\) characterize, respectively, weak and strong stratification regimes of the unstable PBL. The two cases considered herein, \(N^2=0\) and \(N^2>0\), represent these two limits.

2.3 Description of the Simulations

For the stably-stratified configuration (\(N^2>0\)), we consider two simulations with two different values of \(L_0/z_\kappa \), in order to study possible Reynolds-number effects (Table 1). These simulations are a continuation of those discussed in Garcia and Mellado (2014), with reference buoyancy Reynolds numbers \(B_0/(\nu N^2)=(L_0/z_\kappa )^{4/3}\) equal to 42 and 117. The first simulation has been continued until \(z_*/L_0\approx 30\), which represents a deep CBL (e.g., \(h\approx 2700\) m for the atmospheric conditions \(B_0=0.005\;\mathrm{m}^2\;\mathrm{s}^{-3}\) and \(N=0.01\;\mathrm{s}^{-1}\), h being defined by the height of the maximum mean buoyancy gradient). The second simulation achieves larger Reynolds numbers but a smaller CBL depth, \(z_*/L_0\approx 20\). Both cases reach well within the equilibrium (quasi-steady) entrainment regime, which starts at \(z_*/L_0\approx \) 10–15.

For the neutrally-stratified configuration (\(N^2=0\)), we need only one simulation because the number of non-dimensional parameters defining the problem is zero (once the Prandtl number has been set to 1). We use data at \(z_*/z_\kappa \approx 475\) and \(z_*/z_\kappa \approx 680\) to compare with the stably stratified cases at those same values of the scale-separation parameter. In addition, we have continued the simulation to achieve larger Reynolds numbers, reaching values \(\sim \) \(10^4\) (last row in Table 1). As the CBL thickens, we have increased the vertical domain size accordingly so that its influence on the flow remains small, which explains the larger grid size for the larger values of \(z_*/z_\kappa \).

The horizontal size of the computational domain is \(3525\,z_\kappa \times 3525\,z_\kappa \) in the case \(L_0/z_\kappa =16\), and \(7630\,z_\kappa \times 7630\,z_\kappa \) otherwise. The thickness \(\delta _0\) used in the initial condition (2) is \(\delta _0\approx 4\,z_\kappa \). Sensitivity studies with respect to changes in the domain size and in the initial condition can be found in Mellado (2012) and Garcia and Mellado (2014).

2.4 Numerical Method

Equation 1 is discretized on a collocated, structured grid using sixth-order, spectral-like compact finite differences (Lele 1992). The discretized equations are advanced in time with a low-storage, fourth-order Runge–Kutta scheme (Carpenter and Kennedy 1994). The divergence-free (or solenoidal) constraint is imposed by using a Fourier decomposition of the pressure-Poisson equation inside the periodic, horizontal planes, factorizing the resulting set of equations along the vertical direction (Mellado and Ansorge 2012).

The vertical grid spacing \(\varDelta z\) satisfies always the relation \(\varDelta z/\eta \lesssim 1.5\), where \(\eta =(\nu ^3/\varepsilon )^{1/4}\) is the Kolmogorov length scale, and \(\varepsilon = \langle \tau '_{ij}\partial _iu'_j\rangle \) is the viscous dissipation rate of turbulence kinetic energy (TKE), \(\tau _{ij}=\nu (\partial _iu_j+\partial _ju_i)\) being the components of the the viscous stress tensor. (At the centre of the CBL, typical values are \(\eta \approx 1.1\,z_\kappa \) in the neutrally stratified case and \(\eta \approx 1.3\,z_\kappa \) in the stably stratified cases, decreasing to about half of those values at the surface.) Details about the grid and grid-resolution sensitivity studies can be found in Mellado (2012) and Garcia and Mellado (2014).

3 Comparison of Large-Scale Properties

As explained in the introduction, we are interested in how differences in the large-scale organization of the flow might affect near-surface properties. For this purpose, we compare the stably-stratified configuration and the neutrally-stratified configuration at a fixed, common value of the outer length scale, \(z_*\), defined in Eq. 6, and hence a fixed, common value of the outer velocity scale, \(w_*\), defined in Eq. 9.

Vertical cross-sections of the enstrophy at \(z_*/z_\kappa \approx 680\). The vertical white bars in the bottom-left corners indicate the outer length scale, \(z_*\) (Eq. 6). The horizontal white bars are located at \(z=h_{\mathrm{PML}}\), the top of the plume-merging layers, and the bars extend a distance \(\lambda _{\mathrm{LSC}}=10h_{\mathrm{PML}}\), the large-scale circulation width. The areas shown are \(1/2\times 1/2\) of the computational areas

Large-scale properties at \(z_*/z_\kappa \approx 680\). \(u_{\mathrm{h}}=(u_1^2+u_2^2)^{1/2}\) is the magnitude of the horizontal velocity. \(T=\langle w'u_i'u_i'/2 + p'w' - u_i'\tau _{i3}'\rangle \) is the vertical turbulent flux of TKE and \(\varepsilon = \langle \tau '_{ij} \partial _iu'_j \rangle \) is the viscous dissipation rate, \(\tau _{ij} = \nu (\partial _iu_j+\partial _ju_i)\) being the components of the viscous stress tensor

The reason for this approach is as follows. As observed in Fig. 1, the depth of the turbulence region in outer-scale units is approximately the same between the two configurations. In particular, the viscous dissipation rate, \(\varepsilon \), drops to zero at the same normalized height \(z/z_*\) in both configurations (Fig. 2b), and \(\varepsilon \) provides a good estimate for the turbulence region. Moreover, when normalized with \(z_*\) and \(w_*\), the profiles of TKE and the different terms in its evolution equation become comparable between the two stratification regimes (Fig. 2a, b). Hence, by fixing \(z_*/z_\kappa \), we can separate the dependence of near-surface properties on the outer length scale, from the dependence on regime-specific large-scale properties, such as the geometry of the large-scale circulations. (Each of these two dependences is represented by the independent variables \(z_*/z_\kappa \) and \(z_*/L_0\), respectively, in the set of non-dimensional variables explained in Sect. 2.2.)

Note that the outer scales evolve at a different rate in each configuration. A good approximation to this temporal evolution is provided by

in the neutral stratification regime, and by

in the strong stratification regime (Fig. 3), in agreement with the corresponding theories (e.g., see Fedorovich et al. 2004; Mellado 2012 and references therein). This one-to-one mapping between time and CBL depth allows us to express the temporal evolution of the CBL in terms of \(z_*\) instead of t, as argued before in Sect. 2.2.

For a given value of the outer length scale, \(z_*\), we observe several differences between the two configurations. One difference that is relevant for the discussion that follows is the entrainment zone. As the stratification increases, the ascending thermals penetrate less deep into the fluid aloft and kinetic energy is increasingly transferred from the vertical direction to the horizontal direction. The r.m.s. of the vertical velocity component decreases in the lower half of the CBL; the r.m.s. of the horizontal velocity components increases everywhere, but more markedly at the CBL top and bottom (Fig. 2a). (We note that the pointwise, maximum values of the r.m.s. of the velocity components, summarized in Table 2, are a poorer indicator of this change in the flow structure.) The increase of \(u_{\mathrm{1,rms}}\) at the CBL top enhances the local, shear-induced mixing between boundary-layer air and free atmosphere air. The resulting entrainment zone is thinner than in the neutrally stratified configuration, where large-scale motions engulf outer, irrotational fluid over a length scale comparable to the CBL depth (Fig. 1).

Another difference is the tendency of the flow to organize itself into wider large-scale motions in the strong stratification regime (Fig. 4b, d). Furthermore, downdrafts tend to occupy a larger area fraction when \(N^2>0\), as deduced from the study of the skewness of the vertical velocity (Fig. 2c). In both regimes, this skewness is positive and increases with height over most of the CBL. This is a general feature of bottom-heating-only convection: the updrafts are narrower than the downdrafts, and the updrafts become more dispersed with height. The approximation

derived by Moeng and Rotunno (1990) for cases with a solid wall at the top, applies as well for the strong stratification regime considered here, having to modify the proportionally coefficient only by 15 %; \(\sigma _{\mathrm{d}}/\sigma _{\mathrm{u}}\) is the ratio between the area fraction of downdrafts and updrafts. Under neutral conditions, the skewness is noticeably smaller for \(z\lesssim 0.9\,z_*\). Further analysis (not shown) reveals that this smaller value is mainly due to a 10 % smaller area fraction of the downdrafts, and not by a substantial change in the structure of the vertical velocity inside the updrafts and downdrafts.

The energetics is also altered by the stratification of the fluid above the CBL: the turbulent buoyancy flux, \(\langle b'w'\rangle \), and the rate of viscous dissipation of TKE, \(\varepsilon \), are 50 % smaller at \(z=0.5\,z_*\) in the stably stratified configuration (Fig. 2b). A large extent of this difference in the buoyancy flux is explained by the differences in the magnitude of the fluctuations of the vertical velocity and the buoyancy. Nonetheless, the correlation coefficient \(\langle b'w'\rangle /(b_{\mathrm{rms}}w_{\mathrm{rms}})\) at \(z=0.5\,z_*\) still varies from \(\approx 0.8\) when \(N^2=0\) to \(\approx 0.7\) when \(N^2>0\) (not shown), which further indicates a change in the organization of the flow.

In the remaining sections, we discuss how these order-one differences in the large-scale properties affect, or are related to, near-surface properties.

Horizontal cross-sections of the buoyancy at \(z_*/z_\kappa \approx 680\). The large black bars in the top-left corners indicate \(\lambda _{\mathrm{LSC}}\), Eq. 25; the small bars indicate \(50\,z_\kappa \). The areas shown are \(5\,z_*\times 5\,z_*\) (less than 1/4 of the computational areas)

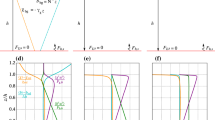

Vertical profiles of buoyancy and velocity statistics. \((\varDelta b)\) is the buoyancy difference with respect to the surface, Eq. 28. Colour shades indicate the scale-separation parameter: light \(z_*/z_\kappa \approx 475\); middle \(z_*/z_\kappa \approx 680\); dark \(z_*/z_\kappa \approx 1280\) (only for \(N^2=0\)). Ticks at the side mark \(z_*/z_\kappa \). Scaling laws are expressed in terms of \(\zeta =z/z_\kappa \)

4 Vertical Profiles

We study first the vertical structure of the first- and second-order moments of the buoyancy and velocity fields. We show that the mean buoyancy profile near the surface, and hence the corresponding flux-profile relationship, is well characterized by the surface scales and z, in agreement with classical similarity theory. However, we need both surface and outer scales to appropriately characterize other properties, such as the variances or the budget equation of the Reynolds stresses. Despite this dependence on outer scales, the dependence on \(N^2\) is only moderate; the major effect of the free atmosphere stratification is that the scaling laws observed near the surface extend deeper into the CBL for the strong stratification regime.

4.1 The Diffusive Wall Layer

Near the surface, the mean turbulent buoyancy flux, the mean buoyancy gradient and the r.m.s. of the buoyancy fluctuations are approximately independent of \(L_0/z_\kappa \), i.e., independent of the stratification (Fig. 5a–c): the vertical profiles corresponding to the case \(N^2=0\) and to different cases \(N^2>0\) collapse on top of each other, up to a height \(\approx \) \(50\,z_\kappa \) in our simulations.

This independence on \(N^2\) implies that the near-surface flow structure described in Mellado (2012) for the neutrally-stratified configuration is applicable as well to the stably-stratified configuration. The height \(10\,z_\kappa \), where \(z_\kappa \) is the surface scale defined in Eq. 4, approximately marks the end of the diffusive wall layer and the beginning of the outer layer. The outer layer is defined as the region where the molecular contribution to the total buoyancy flux is negligibly small (less than 4 % in the configurations of penetrative convection considered here). Descending from this height towards the surface, the turbulent buoyancy flux decreases (Fig. 5a) and the molecular buoyancy flux increases (Fig. 5b). Both become comparable at a height equal to the buoyancy gradient thickness

(Kraichnan 1962; Chillà and Schumacher 2012). This height is slightly larger than \(4\,z_\kappa \) for the range of Rayleigh numbers achieved in our simulations, in agreement with data from Rayleigh–Bénard convection. [\((\varDelta b)_\infty \) is the buoyancy difference between the surface and the CBL; it is defined in Eq. 28 and discussed in detail in Sect. 7.] Below a height equal to \(\delta _b\), the molecular contribution dominates, accounting for the total buoyancy flux at the surface.

Inside the diffusive wall layer, \(\partial _z\langle b\rangle \) and \(b_{\mathrm{rms}}\) are also approximately independent of \(z_*/z_\kappa \), and of order one when normalized with \(z_\kappa \) and \(B_0\). This result further confirms the use of surface scales to characterize these flow properties near the surface.

In contrast to the buoyancy-related quantities just considered, pure velocity statistics near the surface depend on the stratification regime (Fig. 5d, e). Moreover, surface scales alone fail to characterize the horizontal velocity component, since normalized profiles of \(u_{\mathrm{1,rms}}\) depend on \(z_*/z_\kappa \) and thus on the outer length scale, \(z_*\). This dependence of near-surface properties on outer-layer properties contradicts the basic assumption made in classical similarity theory.

4.2 The Outer Layer

Within the lower part of the outer layer (\(z\gtrsim 10\,z_\kappa \)), the clearest variation with height is observed in the stably-stratified cases. On the one hand, the mean buoyancy gradient varies as

between \(z\approx 30\,z_\kappa \) and \(z\approx 200\,z_\kappa \), with \(c_{b1}\approx 0.3\) (Fig. 5b). This scaling with height agrees with the prediction derived from classical similarity theory (Prandtl 1932; Obukhov 1946; Priestley 1954). On the other hand, the r.m.s. of the buoyancy fluctuation and the r.m.s. of the vertical velocity are well approximated by

and by

respectively (Fig. 5c, d). These two scaling laws disagree with the predictions \(b_{\mathrm{rms}}\propto z^{-1/3}\) and \(w_{\mathrm{rms}}\propto z^{1/3}\) made according to classical similarity theory, which further demonstrates the dependence of near-surface properties on outer-layer properties. Moreover, the different scaling laws of the first- and second-order moments of the buoyancy field indicate a duplicity of characteristic scales—one single buoyancy scale implies the same scaling law, according to dimensional analysis.

In the neutrally-stratified case, the vertical profiles deviate from the power laws and the logarithmic law observed before (Fig. 5b–d). However, as the CBL deepens and \(z_*\) increases, the profiles tend towards those found in the strong stratification regime. In Sect. 5, we argue that this behaviour is caused by the large-scale circulations, which, for a given \(z_*/z_\kappa \), affect more strongly the small-scale motions near the surface when \(N^2=0\). As the CBL deepens and the scale-separation parameter \(z_*/z_\kappa \) increases, the profiles in each stratification regime become more similar to each other. Still, an effect of the outer scales near the surface seems to remain because \(w_{\mathrm{rms}}\), when \(N^2=0\), is better approximated by

than by Eq. 15. This dependence further supports the existence of a duplicity of characteristic scales inside the near-surface region, since surface scaling collapses the profiles of \(w_{\mathrm{rms}}\) for different CBL depths onto a single curve, but this curve is different in each stratification regime.

4.3 Discussion

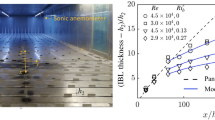

The scaling laws that we observe in our simulations are consistent with previous data. The flux-profile relationship, Eq. 13, including the proportionality constant \(c_{b1}\approx 0.3\), agrees with the asymptotic limit for strongly unstable conditions in commonly used flux-profile relationships (Grachev et al. 2000; Wilson 2001). The exponent \(-0.45\) in the power law for \(b_{\mathrm{rms}}\) compares favourably with the intervals \((-1/2,-1/3)\) and \((-0.8,-0.3)\) reported, respectively, from atmospheric measurements (Wyngaard et al. 1971) and from laboratory experiments and simulations (see review in (Du Puits et al. 2007; Mellado 2012). The logarithmic law for \(w_{\mathrm{rms}}\) agrees with results from laboratory experiments and simulations (Adrian 1996; Fernandes and Adrian 2002), and it fits atmospheric data as well as the power laws that are commonly used (Fig. 6).

How to rationalize these scaling laws, however, remains an open question. Adrian (1996) assumes that the outer scale \(w_*\) is the only characteristic velocity scale inside the overlap region between the outer and the surface layers. A matched asymptotic expansion of the functional forms of the corresponding profiles inside each layer yields then the scaling laws \(b_{\mathrm{rms}}\propto z^{-1/2}\) and \(w_{\mathrm{rms}}\propto \ln z\). Our data support these scaling laws; our data, however, also contradict the assumption that \(w_*\) is the only characteristic scale in the overlap region: curves in Fig. 5c, d corresponding to different values of \(z_*/z_\kappa \) (i.e., different \(w_*/w_\kappa \)) collapse on top of each other when normalized with surface scales, which implies that those statistical properties depend on the surface scales but not on the outer scale \(w_*\).

Standard deviation of the vertical velocity in mixed-convection conditions; L is the Obukhov length, and \(u_*\) is the surface friction velocity. Figure from Panofsky et al. (1977), modified by adding a logarithmic fit to the data

Further analysis reveals that, in general, near-surface dynamics depends not only on surface scales but also on outer scales, even though properties, such as \(w_{\mathrm{rms}}\), do not reflect this dependence directly. This non-trivial dependence on outer scales is further illustrated by the analysis of the evolution equation of the normal Reynolds stresses,

The vertical turbulent fluxes are defined by \(T_{11}=\langle w'(u_1')^2-2u_1'\tau _{13}'\rangle \) and \(T_{33}=\langle (w')^3+2p'w'-2w'\tau _{33}'\rangle \), the viscous dissipation rates are defined by \(\varepsilon _{11}=2\langle \tau '_{i 1} \partial _iu'_1 \rangle \) and \(\varepsilon _{33}=2\langle \tau '_{i 3} \partial _iw' \rangle \), and the magnitude of the pressure-strain correlation is defined by

In both regimes, \(\Pi \) increases with time as the CBL deepens and the scale-separation parameter, \(z_*/z_\kappa \), increases (Fig. 7a). According to the evolution equation of \(w_{\mathrm{rms}}^2\), this increase would suggest a direct influence of the outer scale \(z_*\) on \(w^2_{\mathrm{rms}}\) similar to that observed in \(u^2_{\mathrm{1,rms}}\) (Fig. 5e), as more kinetic energy is transferred from the vertical to the horizontal directions. However, the turbulent transport term in the evolution equation of \(w^2_{\mathrm{rms}}\) increases at the same rate as \(2\Pi \), so that their difference, \(- \partial _z T_{33}-2\Pi \), remains constant in time below \(100\,z_\kappa -200\,z_\kappa \) (Fig. 7b). The viscous dissipation term balances the remaining \({\approx }25 \%\) of the source term \(2\langle b'w'\rangle \), and \(w^2_{\mathrm{rms}}\) remains constant near the surface as the CBL deepens, i.e., independent of the outer scale \(z_*\) (or \(w_*\)).

In contrast, the term \(- \partial _z T_{11}+\Pi \) in the evolution equation of \(u^2_{\mathrm{1,rms}}\) increases with time as the CBL deepens and \(z_*\) increases (Fig. 7a). In the stably-stratified cases, the viscous dissipation term increases at the same rate and balances almost all of this source of horizontal kinetic energy, since \(-\varepsilon _{11}/(\Pi -\partial _zT_{11})\approx -1\). The cause for this balance is that the integral time scale is much shorter than the characteristic time associated with the evolution of the CBL depth, and the system is quasi-steady. Differently, only \(\approx \)80 % of the term \(- \partial _z T_{11}+\Pi \) is balanced by the viscous dissipation in the neutral stratification regime (dashed, red lines in Fig. 7a). In this case, the characteristic time associated with the evolution of \(z_*\) is the same as the integral time scale of the turbulent fluctuation, and \(u^2_{\mathrm{1,rms}}\) is unsteady near the surface, even though \(w^2_{\mathrm{rms}}\) is steady. We show in Sect. 5 that this difference between \(u^2_{\mathrm{1,rms}}\) and \(w^2_{\mathrm{rms}}\) near the surface is because the spectrum of \(u^2_{\mathrm{1,rms}}\) is dominated by large scales, whereas the spectrum of \(w^2_{\mathrm{rms}}\) is dominated by small and intermediate scales; thus, \(w^2_{\mathrm{rms}}\) is characterized by time scales smaller than the integral time scale, and \(w^2_{\mathrm{rms}}\) remains in dynamical equilibrium even when \(N^2 = 0\).

Budget equation of the Reynolds stresses, Eq. 17. Colour shades indicate the scale-separation parameter: light \(z_*/z_\kappa \approx 475\); dark \(z_*/z_\kappa \approx 680\). Ticks at the side mark \(h_{\mathrm{PML}}/z_\kappa \). The normalized dissipation terms are \(-\varepsilon _{11}/(\Pi -\partial _zT_{11})\) in panel a, and \(-\varepsilon _{33}/(2\langle b'w'\rangle -\partial _zT_{33}-2\Pi )\) in panel b; dissipation curves in the stable case end at \(z_*/z_\kappa \) because of the poor statistical convergence above that height

In summary, buoyancy and velocity statistics demonstrate the need for a duplicity of characteristic scales to appropriately describe the near-surface region in free convection: surface scales, \(\{z_\kappa ,\, B_0\}\), and outer scales, \(\{z_*,\, B_0,\, N\}\).

5 Spectral Analysis

By means of the spectral analysis of the buoyancy and velocity fields, we show in this section that the flow near the wall organizes into a hierarchy of circulations. This hierarchy is established by the merging of smaller plumes into larger ones, starting at the surface scales and ending at the large-scale circulations. This hierarchy of circulations is approximately independent of the stratification in the free atmosphere; its depth, however, increases with \(N^2\), similarly to the depth of the scaling laws presented in Sect. 4.

We use azimuthally integrated two-dimensional spectra and cospectra inside the horizontal plane; for instance,

for the buoyancy field, where \(\kappa _i\) is the wavenumber along the direction \(\hat{\mathbf {e}}_i\), \(\kappa =(\kappa _1^2+\kappa _2^2)^{1/2}\) is the wavenumber along the radial direction, and \(\theta \) is the azimuthal angle (Wyngaard 2010). [Although the two-dimensional spectra of the horizontal velocity is not azimuthally symmetric (see, e.g.,Gibbs and Fedorovich 2014), the azimuthally integrated spectra proves more convenient for our analysis.] Spectra and cospectra are presented in the premultiplied form

where \(\lambda =2\pi /\kappa \) is the wavelength along the radial direction, so that

holds. (The dependence on time is not shown explicitly for notational convenience.)

To improve statistical convergence, we have averaged the spectra in time within an interval \(0.5\,z_*/w_*\) in the stably-stratified case, and within an interval \(0.1\,z_*/w_*\) in the neutrally-stratified case, and we have applied a Daniell filter with a window size of 3 spectral modes (von Storch and Zwiers 1999).

Premultiplied spectra at \(z_*/z_\kappa \approx 680\) as a function of the radial wavelength, \(\lambda \), and height, z (cf. Eq. 20): top row neutrally-stratified case; bottom row stably-stratified case. Solid lines mark the local spectral maxima at each wavelength

5.1 Buoyancy and Buoyancy Flux

Near the surface, the main spectral contribution to \(\langle b'^2\rangle \) is approximately independent of the stratification regime (Fig. 8a, e): in both cases, the buoyancy spectra concentrate within a distance \(\approx 10\,z_\kappa \) from the surface, and the spectra have a dominant wavelength \(\lambda \approx 50\,z_\kappa \). This small-scale signal corresponds to the sheet-like thermals observed in Fig. 4a, c, a well-known near-surface flow structure in free convection (see, e.g.,Stull 1988; Chillà and Schumacher 2012).

Associated with this small-scale signal in the buoyancy spectra, the co-spectra between the buoyancy and the vertical velocity component develop a local maximum at \(\lambda \approx 50\,z_\kappa \) (Fig. 8b, f). The reason for this maximum is that w is zero at the surface, its magnitude increasing upwards while that of b decreasing, so that their product peaks at \(z \approx 10\,z_\kappa \).

As with \(\phi _{bb}\), \(\phi _{bw}\) near the surface is also approximately independent of \(N^2\) and \(z_*/z_\kappa \) when normalized with \(z_\kappa \) and \(B_0\). This result shows that surface scales characterize not only the vertical profiles, but also the complete spectral distribution of these two flow properties near the surface.

Beyond \(z\approx 10\,z_\kappa \), inside the outer layer, most of the contribution to the turbulent buoyancy flux stems from a bandwidth that is centred around the diagonal line

(Fig. 8b, f). The growth with height of the dominant wavelength in \(\phi _{bw}\) has been observed before in field measurements (Kaimal et al. 1976) and large-eddy simulations (Schmidt and Schumann 1989). The interpretation thereof is that, as they rise, small plumes (or thermals, or both) coalesce into fewer plumes that are farther apart in the horizontal directions (cf. discussion on the skewness in Sect. 3). Here, we find that this growth is approximately linear and well approximated by Eq. 22.

In contrast to the near-surface structure, the outer-layer structure is strongly influenced by the stratification. In the stably-stratified cases, plume coalescence continues until a height at which the dominant wavelength \(\lambda _{bw}\) becomes larger than the CBL depth (Fig. 8f). Beyond that height, plumes ascend without further merging and in the form of towers (cf. Fig. 1b). An explanation for this structural change is that plumes have already acquired a vertical velocity that is comparable to the horizontal velocity (cf. Fig. 5d, e), so that plumes rise faster than the rate at which nearby plumes are brought together and merge.

In the neutrally-stratified case, a second, stronger maximum in the co-spectrum \(\phi _{bw}\) appears at \(\lambda \approx 0.7\,z_*\) (Fig. 8b), and plume coalescence ends closer to the surface. This large-scale signal extends from the CBL top until near the surface, and accounts for the larger buoyancy flux in the CBL mixed layer under neutral conditions (cf. Fig. 2b). Next to the surface, below \(z\approx 4\,z_\kappa \), this large-scale signal also contributes to \(\phi _{bb}\) (Fig. 8a) and leads to 10 % larger \(b_{\mathrm{rms}}\) when \(N^2=0\) (Fig. 5c). Visually, this large-scale contribution manifests as a large-scale cellular pattern in which the sheet-like thermals tend to organize (Fig. 4a and, to a lesser degree, Fig. 4c).

The region of negative \(\phi _{bw}\) observed in Fig. 8f at \(z\approx z_*\) and wavelengths comparable to \(z_*\) corresponds to the entrainment zone that develops in the stably-stratified case. This region has been discussed in detail by Garcia and Mellado (2014) and is not further considered here.

5.2 Velocity

The vertical variation of the dominant wavelength in the cospectra \(\phi _{bw}\) along the line \(\lambda _{bw}=5\,z\) indicates that, at a given height z, the buoyancy force redirects upwards the motions with a wavelength \(\approx 5\,z\) most efficiently. Consequently, the wavelength of the maximum of the spectra of the vertical velocity component follows that line, slightly above as a result of vertical advection, along the line

(Fig. 8c, g). The magnitude of this maximum increases with height as the plumes and thermals accelerate. Concomitantly, the spectra of the horizontal velocity component have a local minimum along the line \(\lambda _{bw}=5\,z\), which splits \(\phi _{uu}\) into two lobes, each with a local maximum (Fig. 8d, h).

This spectral structure is consistent with previous data. The linear increase with height of the dominant wavelength in \(\phi _{ww}\) agrees with that observed in the unstable PBL (Kaimal and Finnigan 1984; Wyngaard 2010). Here, we find that \(\lambda _{ww}= 3\ z\) provides a good approximation to that linear increase, in both stratification regimes. Likewise, the broadband character of \(\phi _{uu}\) in the lower lobe agrees with that observed near the surface in atmospheric measurements (Kaimal and Finnigan 1984; Wyngaard 2010) and in Rayleigh–Bénard convection (Verdoold et al. 2008; van Reeuwijk et al. 2008).

Sketch illustrating the hierarchy of circulations that defines the plume-merging layer (cf. Sect. 6). The hierarchy is established by the merging of smaller plumes into larger ones, starting at the surface scales and ending at the large-scale circulations. In this sketch, only three levels at heights \(\{z_1\) (red), \(2z_1\) (green), \(3z_1\) (blue)\(\}\) are shown, where \(z_1\gg 10\,z_\kappa \)

This structure can be interpreted as a hierarchy of oblate circulations with an aspect ratio 5:2 (Fig. 9), and which represents the accumulating process of plume coalescence. From \(\phi _{ww}\) (Fig. 8c, g), we infer that the velocity magnitude associated with each circulation increases with its size, and that the size of each circulation grows proportionally to the distance of its centre from the surface. From \(\phi _{uu}\) (Fig. 8d, h), we infer that all those circulations are attached to the surface, since \(\phi _{uu}\) near the surface (\(z\lesssim 5\,z_\kappa \)) is non-zero for a wide interval of wavelengths. The upper and the lower lobes of \(\phi _{uu}\) correspond to the upper and the lower branches of the circulations. Such an attached-eddy flow structure near the surface, with different features, is also characteristic of wall-bounded shear flows (Townsend 1976; Jimenez 2013).

For a given height within this hierarchy of circulations, \(\phi _{ww}\) is approximately constant in time, i.e., independent of \(z_*/z_\kappa \) and hence independent of the CBL depth (Fig. 10). \(\phi _{ww}\) is also well represented, to leading order, by a piecewise-linear variation with respect to \(\log _{10}\lambda \), with a maximum at \(\lambda \approx \lambda _{ww}\). This feature is observed in both stratification regimes. Hence, for a given height near the surface,

Substituting \(\lambda _{ww}(z)\) from Eq. 23 into this relation leads to \(\langle w'w'\rangle \propto (\log _{10} z)^2\), i.e., the logarithmic law of \(w_{\mathrm{rms}}\) observed in Sect. 4.

We also note that a logarithmic variation of \(\phi _{ww}\) for \(\lambda <\lambda _{ww}\) as observed above implies more kinetic energy in the intermediate scales \(50\,z_\kappa <\lambda <\lambda _{ww}\) than the energy corresponding to the 2/3 power law of Kolmogorov’s theory (Fig. 10). One possible explanation for this deviation is that, at a given height, part of the kinetic energy at \(\lambda <\lambda _{ww}\) has been transported from below and results from the buoyancy force working directly on those intermediate scales (Fig. 8b, f). This deviation would suggest that the concept of the inertial cascade alone is insufficient to characterize the near-surface region in free convection; larger Reynolds numbers, however, might be necessary to draw a definitive conclusion about these details of the spectral structure near the surface.

Spectra of the vertical velocity at different heights within the lower half of the plume-merging layer, as indicated by the colours. Colour shades indicate the scale-separation parameter: light \(z_*/z_\kappa \approx 475\); middle, \(z_*/z_\kappa \approx 680\); dark \(z_*/z_\kappa \approx 1280\) (only for \(N^2=0\)). Ticks at the bottom mark \(\lambda _{ww}\), Eq. 23. Scaling laws are expressed in terms of \(\xi =\lambda /z_\kappa \)

5.3 The Large-Scale Circulations

The hierarchy of circulations ends up in one spectral maximum in \(\phi _{ww}\) far from the surface (Fig. 8c, g) and one spectral maximum in \(\phi _{uu}\) near the surface (Fig. 8d, h). Within each regime, both maxima occur at the same wavelength, \(\lambda _{\mathrm{LSC}}\), and this wavelength is proportional to the CBL depth. We find

in the neutral stratification regime, and

in the strong stratification regime. At the same time, the magnitudes of each of these two maxima are proportional to the maximum r.m.s. of the corresponding velocity component, and thus proportional to the outer velocity scale, \(w_*\) (cf. Fig. 2a; Table 3). Hence, we associate these maxima with large-scale circulations, a form of large-scale motion that is characteristic of free convection (see, e.g.,Stull 1988; Chillà and Schumacher 2012). The width of the large-scale circulation is then approximately equal to \(\lambda _{\mathrm{LSC}}\). The large-scale patterns visualized in Figs. 1 and 4b, d support this estimate.

The interval \(0.7\,z_*<\lambda _{\mathrm{LSC}}<2.5\,z_*\) spanned between the neutral and strong stratification regimes is consistent with previous data. Kaimal et al. (1976) found intermediate values \(\lambda _{\mathrm{LSC}}\approx 1.5\,h\) in the unstable PBL under mixed convection conditions. [Recall that the CBL depth, h, is commensurate with the outer length scale, \(z_*\) (cf. Sect. 2.2).] Schmidt and Schumann (1989) found large-scale circulation widths close to \(2\,h\) in their large-eddy simulations of the strong stratification regime considered here. The upper bound \(\lambda _{\mathrm{LSC}}\approx 2.5\,z_*\) also compares favourably with the results obtained by de Roode et al. (2004) from large-eddy simulations of a CBL with an imposed capping inversion, and with entrainment ratios similar to those of the stably-stratified cases studied here (\(\min _{z}\{\langle b'w'\rangle \}/B_0\approx -0.12\); for details, see Garcia and Mellado 2014). Last, the increase from \(\lambda _{\mathrm{LSC}}\approx 0.7\,z_*\) to \(\lambda _{\mathrm{LSC}}\approx 2.5\,z_*\) between the neutral and strong stratification regimes is consistent with the value \(\lambda _{\mathrm{LSC}}\gtrsim 4\,H\) observed by Bailon-Cuba et al. (2010) in Rayleigh–Bénard convection, H being the cell height, since the upper plate in a Rayleigh–Bénard convection cell may be interpreted as an infinitely strong capping inversion in a CBL.

The increase of \(\lambda _{\mathrm{LSC}}\) with \(N^2\) can be physically understood as follows. As \(N^2\) increases, the horizontal velocity intensifies in the lower half of the outer layer, above \(10\,z_\kappa \)–\(20\,z_\kappa \) (cf. Figs. 2a, 5e), while the vertical velocity weakens (cf. Figs. 2a, 5d). Hence, the plumes (or thermals, or both) need to accelerate during a longer time to acquire a vertical velocity that is comparable to the horizontal velocity, and that allows them to escape the hierarchy of circulations. Since part of this acceleration is associated with plume coalescence, a longer acceleration time implies a deeper hierarchy of circulations, which yields wider large-scale circulations.

The increase of \(\lambda _{\mathrm{LSC}}\) with \(N^2\) could also be associated with a second mechanism. By pushing the large-scale circulations closer together, the intensification of the horizontal velocity could facilitate plume merging at the large scales. This mechanism would bypass the process of plume coalescence that defines the hierarchy of circulations, and the resulting dominant wavelengths in \(\phi _{bw}\) and \(\phi _{ww}\) would be larger than \(\lambda _{bw}=5\,z\) and \(\lambda _{ww}=3\,z\). However, we do not observe such a behaviour; all our data tend to follow those linear relations, despite the more than three-fold variation of \(\lambda _{\mathrm{LSC}}\) between regimes. This result indicates that the large-scale circulations do not alter the process of plume coalescence, but the large-scale circulations are rather an outcome of such a process. Nonetheless, this second mechanism could gain relevance with larger ratios between \(u_{\mathrm{1,rms}}\) and \(w_{\mathrm{rms}}\), such as in cases with an imposed capping inversion, or in Rayleigh–Bénard convection. Radiative cooling or latent heat effects could also favour this second mechanism by accelerating the flow inside the downdrafts, increasing thereby the kinetic energy directly at the large scales, and thus increasing the magnitude of the horizontal velocity near the surface.

6 The Plume-Merging Layer

The depth of the hierarchy of circulations grows proportionally to the CBL depth, since the width of the largest element of the hierarchy is commensurate with the large-scale circulation width and \(\lambda _{\mathrm{LSC}} \propto z_*\) (cf. Eq. 25). Concomitantly, the spectra of the buoyancy, the vertical buoyancy flux and the vertical velocity near the surface—and hence the corresponding profiles discussed in Sect. 4—become increasingly constant in time as the CBL deepens and similar between regimes (cf. Figs. 8, 10). The major difference is the deeper vertical extent of this near-surface structure when \(N^2>0\). In contrast, the spectra of the horizontal velocity near the surface vary significantly among times and cases. The reason is that, unlike the buoyancy and the vertical velocity, where the spectra concentrate in the wavelength interval \((10\,z_\kappa ,5\,z)\), the horizontal velocity contains significant contributions from \((5\,z,\lambda _{\mathrm{LSC}})\). Hence, u near the surface is more sensitive to the large-scale circulations than w and b, and thereby more sensitive to outer-layer variables (cf. Fig. 5e).

The behaviour summarized in the previous paragraph suggests a structural definition of a new near-surface layer in free convection: the plume-merging layer (PML). The PML is defined as the region next to the surface that can be described, at least partly, in terms of the hierarchy of circulations that is sketched in Fig. 9.

We can identify the PML with the inner layer that is often used to describe the vertical structure of wall-bounded flows (see, e.g., Garratt 1992; Mellado 2012), since some properties inside the plume-merging layer tend to become independent of the outer-layer variables \(N^2\) and \(z_*\). However, some other properties, such as \(u_{\mathrm{1,rms}}\), also depend on the outer-layer variables, and the new term PML aims to reflect this dependence.

The PML depth, \(h_{\mathrm{PML}}\), is proportional to the large-scale circulation width, but the proportionality constant remains to be defined, e.g. as

such that the scaling laws 13–15 apply over a vertical distance approximately equal to \(h_{\mathrm{PML}}\) (cf. Table 3; Fig. 5a–c). From Eq. 25, this definition yields

in the neutral stratification regime, and

in the stable stratification regime. Hence, for the same CBL depth, the plume-merging layer in the strong stratification regime penetrates deeper into the outer layer, and \(h_{\mathrm{PML}}\) is approximately four times larger than in the neutral stratification regime. We also note that \(h_{\mathrm{PML}}\) is between 2 and 2.5 times larger—depending on the exact definition of the CBL depth, h—than the thickness 0.1h commonly used to define the depth of a constant-flux (or surface) layer (see, e.g., Garratt 1992; Wyngaard 2010).

We have already mentioned two possible reasons for the plume-merging layer in the stably stratified case to be noticeably deeper than in the neutrally stratified case. First, for a given CBL depth, the entrainment zone recedes and becomes thinner when stratification increases (cf. Sect. 3). Second, the intensification of horizontal velocity with increasing stratification demands an acceleration and coalescence of ascending plumes for a longer time, until they acquire a vertical velocity comparable to the horizontal one (cf. Sect. 5.3). We emphasize, however, that the hierarchical structure inside the plume-merging layer unfolds bottom-up, from smaller to larger sizes, and the role of the stratification in the fluid above the CBL is merely to define the PML depth. As a corollary, the flow structure inside the PML is independent of entrainment-zone properties in the cases considered in our study. Still, properties of scalar fields different from the buoyancy can depend on entrainment zone properties.

For the cases of a CBL growing into a linearly stratified fluid considered in our study, the buoyancy field is dominated by a bottom-up diffusion part. It remains to be ascertained how the near-surface flow structure changes when the buoyancy field depends more strongly on a top-down diffusion part, such as in cases with an imposed capping inversion, or in Rayleigh–Bénard convection, or when radiation or latent heat effects alter the CBL dynamics (see, e.g., de Roode et al. 2004).

7 Buoyancy Transfer Law

Integrating Eq. 13 yields the transfer law

which relates the surface buoyancy flux, \(B_0\), with \(\varDelta b\), the mean buoyancy difference between the surface and an arbitrary height z within the interval \(30\,z_\kappa \lesssim z\lesssim h_{\mathrm{PML}}\). The proportionality constant \(c_{b1}\) has already been discussed in Sect. 4. The constant of integration, \((\varDelta b)_\infty \), is the buoyancy decrease across the plume-merging layer once \(h_{\mathrm{PML}}\) becomes large enough to neglect the last term in Eq. 28. Fitting Eq. 28 to our data provides the range \((\varDelta b)_\infty /b_\kappa \approx 3.9-4.35\) (Fig. 5f). As observed in Fig. 11a, \((\varDelta b)_\infty \) is increasingly well approximated by \(\langle b\rangle (0,t)-N^2z_*\) with increasing \(z_*/z_\kappa \) and \(L_0/z_\kappa \).

The buoyancy difference \((\varDelta b)_\infty \) is often used to construct the bulk transfer law

where the prefactor C is a function of \(z_*/z_\kappa \) and \(z_*/L_0\), to be determined. By definition, \(C=[(\varDelta b)_\infty /b_\kappa ]^{-4/3}\), so that the range \((\varDelta b)_\infty /b_\kappa \approx 3.9-4.35\) obtained before implies \(C\approx 0.14-0.16\). This result is consistent with the interval (0.1, 0.2) obtained from laboratory experiments on penetrative convection, and from atmospheric measurements and theoretical studies of a CBL over aerodynamically smooth surfaces (see, e.g., Beljaars 1994; Zilitinkevich et al. 1998, 2006).

Temporal evolution of \((\varDelta b)_\infty \) (symbols), using two different normalizations (a, b). Colour shades indicate the scale-separation parameter: light \(z_*/z_\kappa \approx 475\); middle, \(z_*/z_\kappa \approx 680\); dark \(z_*/z_\kappa \approx 1280\) (only for \(N^2=0\)). The curves in a indicate \(\langle b\rangle (0,t)-N^2z_*\)

Our results also agree with data from Rayleigh–Bénard convection. In this context, Eq. 29 is expressed as

where

is the Nusselt number, and

is the Rayleigh number. Figure 11b plots the compensated form of this bulk transfer law, \(Nu\, Ra_{\mathrm{eq}}^{-1/3} = 2^{-4/3}C\), as a function of the equivalent Rayleigh number \(Ra_{\mathrm{eq}} = 16\,Ra\). The factor 16 in this definition stems from the interpretation of the CBL as half a convection cell, whereby \(z_*\) and \((\varDelta b)_\infty \) represent half the height and half the buoyancy difference between the two plates of the convection cell (Adrian 1996; Mellado 2012). This interpretation proves convenient to compare data from different configurations (Fig. 11b). The mild but robust decrease of C with Ra in all the data contradicts the assumption made in classical similarity theory that C is independent of \(z_*\), and hence independent of the Rayleigh number.

We find that the bulk transfer law (29) depends on the stratification of the fluid above the CBL, but just moderately: C is \(\approx \)10 % smaller in the stably stratified case. This dependence is relatively small, since it is comparable to the spread in the available data and therefore difficult to measure. This small change in C contrasts with the more than threefold variation of the large-scale circulation width between regimes (cf. Sect. 5.3), which suggests a small role of the large-scale circulations in defining the buoyancy transfer law. The reason is that the buoyancy flux is dominated by small and intermediate scales (cf. Sect. 6).

An alternative bulk transfer law can be obtained by particularizing Eq. 28 at a height \(z=z_0\), which yields

\((\varDelta b)_0=(\varDelta b)_\infty -\langle \varDelta b\rangle (z_0)\) is the buoyancy difference between \(z=z_0\) and some level inside the CBL. This form of a bulk transfer law is commonly used in the case of an aerodynamically rough surface, \(z_0\) being then the aerodynamic roughness length (see, e.g., Garratt 1992; Wyngaard 2010). Despite its similarity, this bulk transfer law is different from the relation

that is derived from Eq. 29 and definition 4. The reason is that, unlike Eq. 33, Eq. 34 accounts for the sharp buoyancy decrease next to the surface (Brutsaert 1982; Sorbjan 1997). For an aerodynamically smooth surface, we find that this decrease is substantial, \(\approx \)80 % of the total variation \((\varDelta b)_\infty \). This sharp buoyancy drop across the diffusive wall layer is approximately independent of the stratification in the fluid above the CBL (Fig. 5f).

8 Summary and Conclusions

We have quantified the effect of a linear stratification in the free atmosphere on near-surface properties in a free convective boundary layer. We have used direct numerical simulation to remove the uncertainty associated with turbulence models near the surface. With help of dimensional analysis, the cases studied in this work represent any combination of free atmosphere stratification, surface buoyancy flux, and CBL depth, as long as the CBL is in one of the following two regimes: a neutral stratification regime, which represents a CBL that grows into a residual layer, and a strong stratification regime that corresponds to the equilibrium (quasi-steady) entrainment regime.

The only atmospheric parameter that we cannot match in our simulations is the Reynolds number. However, well-known CBL properties are faithfully reproduced, and the observed dependence on the Reynolds number of the properties studied in this work is negligibly small compared to the dependence on the stratification regime.

We have found that the mean buoyancy profile varies as \(\langle b\rangle \propto (B_0^2/z_\kappa )^{1/3} (z/z_\kappa )^{-1/3}\), which agrees with the classical similarity theory. In contrast, the r.m.s. of the buoyancy fluctuation and the r.m.s. of the vertical velocity deviate from that theory: they vary as \(b_{\mathrm{rms}}\propto (B_0^2/z_\kappa )^{1/3} (z/z_\kappa )^{-0.45}\) and \(w_{\mathrm{rms}}\propto (B_0z_\kappa )^{1/3} \ln (z/z_\kappa )\). This contrast shows that surface models should consider both outer scales and surface scales simultaneously, and not just one or the other. In our study, the surface length scale is \(z_\kappa =(\kappa ^3/B_0)^{1/4}\), \(\kappa \) being the molecular diffusivity.

The scaling laws presented above become independent of the stratification regime. Regarding the proportionality constants, only that of \(w_{\mathrm{rms}}\) exhibits a clear but moderate dependence on \(N^2\), being approximately 30 % larger under neutral conditions. On the other hand, the depth over which the scaling laws are observed strongly increases with the stratification in the free atmosphere.

We have introduced the concept of the plume-merging layer to better understand these findings. This layer is conceptually different from the constant-flux (or surface) layer. According to spectral analysis, the flow structure near the surface can be understood as a hierarchy of oblate circulations that have an aspect ratio 5:2 and that remain attached to the surface. The hierarchy is established by smaller plumes merging into larger ones, starting at the surface scales and ending at the large-scale circulations. This flow structure defines the plume-merging layer.

The structure of the plume-merging layer is independent of the stratification regime, but its depth, \(h_{\mathrm{PML}}\), strongly increases with stratification. The exact definition of \(h_{\mathrm{PML}}\) has been chosen such that it represents the depth over which the scaling laws presented above are observed. The result is \(h_{\mathrm{PML}}\approx 0.07\,z_*\) in the neutral stratification regime and \(h_{\mathrm{PML}}\approx 0.25\,z_*\) in the strong stratification regime; \(z_*\) is an outer length scale that is commensurate with the CBL depth. The large-scale circulation width is \(\lambda _{\mathrm{LSC}}= 10\,h_{\mathrm{PML}}\), so that \(\lambda _{\mathrm{LSC}}\) increases from \(0.7z_*\) in the neutral stratification regime to \(2.5z_*\) in the strong stratification regime. The buoyancy transfer law is similar between regimes, despite the order-one variation of the large-scale circulation width.

The implication of our results for atmospheric models is two-fold. First, the buoyancy transfer law needed in mixed-layer and single-column models corresponds to that predicted by the classical similarity theory, independently of the stratification in the free atmosphere, even though other near-surface properties are inconsistent with such a theory. Second, for the buoyancy transfer law to apply in the equilibrium (quasi-steady) entrainment regime of a free convective boundary layer, the model first level can be within 20–25 % of the CBL depth, and not necessarily within 10 %.

This work has considered flat, aerodynamically smooth surfaces, which only covers a small interval of the conditions typically found in nature. The bulk transfer law relating the buoyancy difference between the surface and the interior of the CBL will be different for an aerodynamically rough surface, and the diffusive wall layer needs to be replaced by the roughness (or interfacial) layer. However, we expect that the characteristics of the plume-merging layer described in this work—in particular, their dependence on the stratification in the free atmosphere—are valid after substituting \(z_\kappa \) by the appropriate surface length scale (provided that the roughness layer is thinner than \(h_{\mathrm{PML}}\)). The reason is that the Reynolds number characterizing the flow within the plume-merging layer, \(h_{\mathrm{PML}}w_*/\nu \), is already \(\sim 10^3\) in our simulations, which, although smaller than in the PBL, is large enough for inertial forces to dominate over viscous forces.

References

Adrian RJ (1996) Variations of temperature and velocity fluctuations in turbulent thermal convection over horizontal surfaces. Int J Heat Mass Transfer 11:2303–2310

Ahlers G, Bodenschatz E, Funfschilling D, Grossmann S, He X, Lohse D, Stevens RJAM, Verzicco R (2012) Logarithmic temperature profiles in turbulent Rayleigh–Bénard convection. Phys Rev Lett 109(114501):1–5

Bailon-Cuba J, Emran M, Schumacher J (2010) Aspect ratio dependence of heat transfer and large-scale flow in turbulent convection. J Fluid Mech 665:152–173

Beljaars ACM (1994) The parametrization of surface fluxes in large-scale models under free convection. Q J R Meteorol Soc 121:255–270

Brasseur JG, Wei T (2010) Designing large-eddy simulation of the turbulent boundary layer to capture law-of-the-wall scaling. Phys Fluids 22(021303):1–21

Brutsaert W (1982) Evaporation Into the atmosphere. D. Reidel Publishing Company, Dordrecht, 299 pp

Businger JA (1973) A note on free convection. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 4:323–326

Carpenter MH, Kennedy CA (1994) Fourth-order 2N-storage Runge-Kutta schemes. Technical Report TM-109112, NASA Langley Research Center

Chillà F, Schumacher J (2012) New perspectives in turbulent Rayleigh-Bénard convection. Eur Phys J E 35(58):1–25

de Roode SR, Duynkerke PG, Jonker HJJ (2004) Large-eddy simulation: how large is large enough? J Atmos Sci 61:403–421

Deardorff JW (1970) Convective velocity and temperature scales for the unstable planetary boundary layer and for Rayleigh convection. J Atmos Sci 27:1211–1213

Dimotakis PE (2000) The mixing transition in turbulent flows. J Fluid Mech 409:69–98

Du Puits R, Resagk C, Tilgner A, Busse FH, Thess A (2007) Structure of thermal boundary layers in turbulent Rayleigh-Bénard convection. J Fluid Mech 572:231–254

Fedorovich E, Shapiro A (2009) Turbulent natural convection along a vertical plane immersed in a stably stratified medium. J Fluid Mech 636:41–57

Fedorovich E, Conzemius R, Mironov D (2004) Convective entrainment into a shear-free linearly stratified atmosphere: bulk models reevaluated through large-eddy simulation. J Atmos Sci 61:281–295

Fernandes RLJ, Adrian RJ (2002) Scaling of velocity and temperature fluctuations in turbulent thermal convection. Exp Thermal Fluid Sci 26:355–360

Garcia JR, Mellado JP (2014) The two-layer structure of the entrainment zone in the convective boundary layer. J Atmos Sci 71:1935–1955

Garratt JR (1992) The atmospheric boundary layer. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 316 pp

Gibbs JA, Fedorovich E (2014) Comparison of convective boundary layer velocity spectra retrieved from large-eddy-simulation and Weather Research and Forecasting model data. J Appl Meteor Climatol 53:377–394

Grachev AA, Fairall CW, Bradley EF (2000) Convective profile constants revisited. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 94:495–515

Grossmann S, Lohse D (2000) Scaling in thermal convection: a unifying view. J Fluid Mech 407:27–56

Jimenez J (2013) Near-wall turbulence. Phys Fluids 25(10):101302

Kaimal JC, Finnigan JJ (1984) Atmospheric boundary layer flows. Oxford University Press, New York, 289 pp

Kaimal JC, Wyngaard JC, Haugen DA, Coté OR, Caughey YISJ, Readings CJ (1976) Turbulence structure in the convective boundary layer. J Atmos Sci 33:2152–2169

Kraichnan R (1962) Turbulent thermal convection at an arbitrary Prandtl number. Phys Fluids 5(11):1374–1389

Lele SK (1992) Compact finite difference schemes with spectral-like resolution. J Comput Phys 103:16–42

Mellado JP (2012) Direct numerical simulation of free convection over a heated plate. J Fluid Mech 712:418–450

Mellado JP, Ansorge C (2012) Factorization of the Fourier transform of the pressure-Poisson equation using finite differences in colocated grids. Z Angew Math Mech 92:380–392

Miralles DG, Teuling AJ, van Heerwaarden CC, de Arellano JVG (2014) Mega-heatwave temperatures due to combined soil desiccation and atmospheric heat accumulation. Nature Geosci 7:345–349

Moeng CH, Rotunno R (1990) Vertical velocity skewness in the bouyancy-driven boundary layer. J Atmos Sci 47:1149–1162

Moin P, Mahesh K (1998) Direct numerical simulation: a tool in turbulence research. Annu Rev Fluid Mech 30:539–578

Monin AS, Yaglom AM (2007) Statistical fluid mechanics. mechanics of turbulence, vol I. Dover Publications, Mineola, 769 pp

Obukhov AM (1946) Turbulence in an atmosphere with a non-uniform temperature. Tr Inst Teo Geofiz Akad Nauk SSSR 1:95–115, in Russian, English trans.: 1971. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 2:7–29

Panofsky HA, Tennekes H, Lenschow DH, Wyngaard JC (1977) The characteristics of turbulent velocity components in the surface layer under convective conditions. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 11:355–361

Pope SB (2000) Turbulent flows. Cambridge University Press, New York, 771 pp

Prandtl L (1932) Meteorologische Anwendung der Strömungslehre. Beitr Phys Atmos 19:188–202

Priestley CHB (1954) Convection from a large horizontal surface. Austr J Phys 7:176–201

Schmidt H, Schumann U (1989) Coherent structure of the convective boundary layer derived from large-eddy simulations. J Fluid Mech 200:511–562

Schumann U (1988) Minimum friction velocity and heat transfer in the rough surface layer of a convective boundary layer. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 44:311–326

Sorbjan Z (1997) Decay of convective turbulence revisited. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 82:501–515

Stull RB (1988) An introduction to boundary layer meteorology. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, 670 pp

Sullivan PP, Patton EG (2011) The effect of mesh resolution on convective boundary layer statistics and structures generated by large-eddy simulations. J Atmos Sci 68:2395–2415

Sullivan PP, Williams JCM, Moeng CH (1994) A subgrid-scale model for large-eddy simulations of planetary boundary-layer flows. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 71:247–276

Tennekes H, Lumley JL (1972) A first course in turbulence. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 300 pp

Townsend AA (1959) Temperature fluctuations over a heated horizontal surface. J Fluid Mech 5:209–241

Townsend AA (1976) The structure of turbulent shear flow, 2nd edn. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 429 pp

van de Boer A, Moene AF, Graf A, Schüttemeyer S, Simmer C (2014) Detection of entrainment influences on surface-layer measurements and extension of Monin–Obukhov similarity theory. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 152:19–44

van Reeuwijk M, Jonker HJJ, Hanjalić K (2008) Wind and boundary layers in Rayleigh-Bénard convection. II. Boundary layer character and scaling. Phys Rev E 77(036312):1–10

Verdoold J, Reeuwijk M, Tummers MJ, Jonker HJJ, Hanjalić K (2008) Spectral analysis of boundary layers in Rayleigh-Bénard convection. Phys Rev E 77(016303):1–8

von Storch H, Zwiers FW (1999) Statistical analysis in climate research. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 484 pp

Wallace JM, Hobbs PV (2006) Atmospheric science, 2nd edn. Elsevier, Burlington, 483 pp

Wilson DK (2001) An alternative function for the wind and temperature gradients in unstable surface layers. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 99:151–158

Wyngaard JC (2010) Turbulence in the atmosphere. Cambridge University Press, New York, 393 pp

Wyngaard JC, Coté OR, Izumi Y (1971) Local free convection, similarity, and the budget of shear stress and heat flux. J Atmos Sci 28:1171–1182

Zilitinkevich S, Grachev A, Hunt JCR (1998) Surface frictional processes and non-local heat/mass transfer in the shear-free convective boundary layer. In: Plate EJ, Fedorovich EE, Viegas DX, Wyngaard JC (eds) Buoyant convection in geophysical flows. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Boston, pp 83–113

Zilitinkevich SS, Hunt JCR, Esau IN, Grachev AA, Lalas DP, Akylas E, Tombrou M, Fairall CW, Fernando HJS, Baklanov AA, Joffre SM (2006) The influence of large convective eddies on the surface-layer turbulence. Q J R Meteorol Soc 132:1423–1455

Acknowledgments

We thank Evgeni Fedorovich, Ned Patton, Peter Sullivan and Jeff Weil for valuable comments and suggestions. The term plume-merging layer introduced here to refer to the attached-eddy layer in free convection was proposed by Evgeni Fedorovich. Computational time was provided by the Jülich Supercomputing Centre. Jens-Henrik Göbbert and Cedrick Ansorge developed the library to efficiently overlap communication and computation used in simulation \(5120^2\times 1792\). Support from the Max Planck Society through its Max Planck Research Groups program is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Mellado, J.P., van Heerwaarden, C.C. & Garcia, J.R. Near-Surface Effects of Free Atmosphere Stratification in Free Convection. Boundary-Layer Meteorol 159, 69–95 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10546-015-0105-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10546-015-0105-x