Abstract

The relationships between species diversity and ecosystem functions are in the focus of recent ecological research. However, until now the influence of species diversity on ecosystem processes such as decomposition or mineral cycling is not well understood. In deciduous forests, spiders are an integral part of the forest floor food web. In the present study, patterns of spider diversity and community structure are related to diversity of deciduous forest stands in the Hainich National Park (Thuringia). In 2005, pitfall trapping and quantitative forest floor sampling were conducted in nine plots of forest stands with one (Diversity Level 1), three (DL 2) and five (DL 3) major deciduous tree species. Species richness, measured with both methods, as well as spider abundance in forest floor samples were highest in stands with medium diversity (DL 2) and lowest in pure beech stands (DL 1). The Shannon-Wiener index and spider numbers in pitfall traps decreased from DL 1 to DL 3, while the Shannon-Wiener index in forest floor samples increased in the opposite direction. Spider community composition differed more strongly between single plots than between diversity levels. Altogether, no general relationship between increasing tree species diversity and patterns of diversity and abundance in spider communities was found. It appears that there is a strong influence of single tree species dominating a forest stand and modifying structural habitat characteristics such as litter depth and herb cover which are important for ground-living spiders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Soil and litter of forests generally contain highly diverse communities with a large number of organisms (De Ruiter et al. 2002; Setälä 2005; Fitter et al. 2005). In soils, the relationship between biodiversity and soil processes is thought to be primarily controlled by the dynamics and interactions in the soil community food web including the plants. It is well established that trophic groups and their interactions in decomposer food webs significantly influence ecosystem functioning, thus warranting a food-web approach when studying the diversity-functioning relationship in soil (Mikola et al. 2002; Wardle 2006).

Spiders as generalist predators are an integral part of the forest floor food web (Weidemann 1976; Schaefer 1991; Wise and Chen 1999). They are linked to the detritivore community by numerous direct and indirect interactions. On the one hand, they can be limited by the densities of their prey populations (Chen and Wise 1999; Wise et al. 1999). On the other hand, they are able to control the abundance of prey organisms such as microbi-detritivorous Collembola, displaying indirect stimulating or retarding top–down effects on decomposition processes and nutrient cycling (Kajak 1995; Hunter et al. 2003; Lawrence and Wise 2004; Wise 2004; Lensing et al. 2005). Species-rich spider communities have been found to regulate prey populations more effectively than less diverse communities (Riechert and Lawrence 1997). However, with increasing diversity of spider coenoses there is also a higher probability of intraguild predation (Wise and Chen 1999) modifying the effects of spiders in trophic cascades and ecosystem processes (Finke and Denno 2005).

In addition to these biotic interactions, spider communities are influenced to a large degree by abiotic environmental factors comprising structural and microclimatic features of the habitat (Hatley and MacMahon 1980; Uetz 1990; Niemelä et al. 1996; Gurdebeke et al. 2003; Oxbrough et al. 2005), which in turn might be affected by forest stand diversity (e.g. via litter diversity and differing decomposition dynamics).

Stand diversity has been found to increase structural diversity which is a key factor for spider communities (Jocque 1973). However, previous studies of the araneofauna of deciduous forests in Central Europe did not directly consider tree species diversity. They either concentrated on stands with only one major tree species (Dumpert and Platen 1985; Stippich 1986; Sührig 1997) or compared different forest stands, which in addition often varied in soil characteristics and their geographic location thus limiting comparability (Heimer and Hiebsch 1982; Hofmann 1986; Irmler and Heydemann 1988; Gurdebeke et al. 2003).

The Hainich National Park (Thuringia, Germany) offers a wide variety of mixed deciduous forest stands, where the influence of tree species diversity on animal communities can be studied under comparable geographic and pedogenetic conditions. The objective of this study was to analyze spider communities of the forest floor in a diversity gradient ranging from pure beech stands to forest stands comprising three and five major deciduous tree species. Since plant diversity has often been found to affect structural and biotic properties of ecosystems (e.g. Gartner and Cardon 2004; Hooper et al. 2005; Scherer-Lorenzen et al. 2005; Unsicker et al. 2006), it might also positively or negatively influence spider communities either directly or indirectly by modifying important habitat features for forest floor species (e.g. spatial and temporal changes in litter structure and microclimate).

Guiding questions were: (i) Are there distinct spatial or temporal patterns of spider species richness or abundance related to different levels of forest stand diversity? (ii) Are there differences in community structure and species composition? (iii) Which factors correlate with observed differences? Can they be attributed to the influence of different stand diversities or do spiders respond to factors independent of tree species diversity?

Materials and methods

Study sites

The Hainich National Park is located at the southern end of the Hainich, a low mountain range in Thuringia, Central Germany, between the cities of Mühlhausen and Eisenach. Mean annual temperature averages from 7.5 to 8.0°C and mean annual precipitation is 600 mm, indicating a subatlantic climate with a slight subcontinental impact in the eastern part (Mönninghoff 1998).

Five study sites were established in the north-eastern part of the national park at about 300–370 m a.s.l. (approx. 51°1′ N, 10°5′ E), 0.5–4 km apart from each other (Fig. 1). Due to former forest management, the national park consists of a wide variety of very different deciduous forest stands on a small scale (Ahrns and Hofmann 1998). A total of nine plots was selected within five study sites (Fig. 1) belonging to three different stand types of increasing diversity levels (DL): one-species stands (DL 1) with beech (Fagus sylvatica L.), three-species stands (DL 2) with beech, ash (Fraxinus excelsior L.) and lime (Tilia cordata Mill. and/or Tilia platyphyllos Scop.) and five-species stands (DL 3) with beech, ash, lime, hornbeam (Carpinus betulus L.) and maple (Acer pseudoplatanus L. and/or Acer platanoides L.) as major tree species (i.e., dominating species as compared to species with just very few trees growing in or at the edge of the stands). Thus, the diversity levels represent a gradient from pure beech stands to complex mixed stands.

Study area in the Hainich National Park with the location of the nine plots at the five study sites (circled). Tree species diversity levels: DL 1 (pure beech stands), DL 2 (mixed stands with three major tree species), DL 3 (mixed stands with five major tree species). Replicates are indicated by letters a, b and c

Each diversity level was replicated three times (plots a, b and c). Phytosociologically, the plots belong to the alliance of beech forests (Galio odorati-Fagion: all DL 1 and DL 2a,c) and oak-hornbeam forests (Carpinion betuli: DL 2b and all DL 3; Mölder et al. 2006). The parent rock is limestone which in most parts is covered by a loess layer of up to 120 cm forming cambisols and partially planosols (Seidel 1995; A. Guckland et al. unpublished data). To control for confounding factors as best as possible in an observational study, plots were chosen to be as similar as possible concerning pedological and biochemical properties of the stands, stand structure and stand age (approx. 80–120 years).

Sampling design

The plots had a size of 50 × 50 m and were fenced to keep out wild game. Six pitfall traps were installed randomly in each of the plots, measuring spider activity. Trapping was done continuously from 27 April to 26 October, 2005, (182 days) and traps were emptied every two weeks. The traps consisted of 0.4 l jars (diameter of the opening 5.5 cm) filled up to one third with a 50% ethylene glycol solution in water, with a few drops of an odourless detergent. A mesh wire cage (mesh size 1.5 cm) with a plastic roof was placed above each trap to keep out small vertebrates and to prevent dilution of the ethylene glycol solution by precipitation.

For measuring spider abundance, samples of the litter layer and the upper 5 cm of the soil layer (Ø 21 cm = 1/28 m2) were taken on 11 May, 3 August and 23 November, 2005, about three meters away from the pitfall traps (six samples per plot) and animals were extracted by heat using the modified high-gradient canister method (Kempson et al. 1963; Schauermann 1982). These samples, comprising the litter layer and the upper soil layer, are termed “forest floor” samples.

Environmental variables

Temperature and relative humidity were recorded continuously during the trapping period by one “HOBO pro H8-32” datalogger attached under the roof of the centermost trap on each plot. The percentage of herb cover was estimated monthly on a 5 × 5 m area surrounding each pitfall trap. The species composition of litter was recorded with litter collectors (buckets with a diameter of 0.6 m) placed close to the traps, collecting falling leaves from August to December, 2005. Litter depth, litter pH, soil moisture and densities of springtails (Collembola) were determined from small forest floor samples (diameter of 5 cm), taken together with the larger samples for spider extraction. Collembolans were extracted by heat (Macfadyen 1961).

Data analyses

To detect differences in spider species richness, spider numbers and activity of selected spider species, analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey’s post hoc test were used in a design with the factor “plot” nested within the factor “diversity level”. Thus, by splitting total variance, plot effects within the diversity levels could be separated from actual effects of the three diversity levels. A second ANOVA comparing the nine plots was used to assess the significance of observed plot effects. They were considered to be relevant only if one of the three plots within a diversity level differed significantly from the other two plots.

Before testing, data were checked for normality of distribution (Shapiro-Wilk) and homogeneity of variance (Bartlett’s test) and if necessary log-transformed. Multiple comparisons were secured by MANOVA (“protected ANOVA”, Scheiner and Gurevitch 1993), which in all cases yielded a statistically significant model (P < 0.001). Analyses were performed using SAS for Windows 8.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

As a measure for species diversity the Shannon-Wiener index was calculated (Magurran 2004).

Data were pooled for pitfall traps because of continuous trapping, whereas forest floor sample data were analyzed separately for each of the three sampling dates.

Principal components analysis (PCA) was used for multivariate analysis of community structure using Canoco for Windows 4.5 (Ter Braak and Šmilauer 2002). Data were log-transformed thus downweighting highly abundant, ubiquitous species. Additionally, species with less than four individuals in the pitfall trap dataset were excluded to reduce the influence of accidental occurrences. Integration of environmental factors was done by redundancy analysis (RDA). Relevance of the selected variables was confirmed by comparing PCA and RDA eigenvalues and by Monte Carlo permutation procedure (Ter Braak and Šmilauer 2002).

Spearman’s rank correlation was performed to test relationships between environmental variables and species richness as well as spider numbers, using SAS for Windows 8.2.

Results

Environmental variables

Diversity level characteristics are summarized in Table 1, with herb cover increasing (F 2, 45 = 58.0; P < 0.001) and litter depth decreasing (F 2, 45 = 34.48; P < 0.001) significantly with increasing tree diversity. Collembolan densities were higher in DL 1 than in DL 2 and DL 3 (F 2, 45 = 24.02; P < 0.001). For herb cover there was also a significant plot effect (F 6, 45 = 9.18; P < 0.001) in DL 2 because of reduced herb cover on plot DL 2c. Temperature and relative humidity were not markedly different between diversity levels, but data could not be analysed statistically due to missing values on some plots after datalogger malfunctions. Soil moisture was not continuously high or low on any diversity level, while litter pH was lowest on the DL 1 plots throughout the year.

Litter composition in the near vicinity of pitfall traps was rather homogeneous (Fig. 2) within DL 1 and DL 2, whereas litter composition between plots of DL 3 differed to a larger degree. Two plots had high proportions of lime (DL 3a and DL 3b) and only a low proportion of beech. DL 3c as the third DL 3 plot, however, was characterized by comparably larger amounts of beech as well as ash and only about 15% lime.

Spider diversity and numbers

In total 6,877 individuals were collected with pitfall traps; 4,463 spiders (65%) were adults belonging to 64 species. Forest floor samples yielded 1,730 individuals with 390 adults (23%) belonging to 32 species with only four of these not caught in pitfall traps. Spider numbers in pitfall traps were dominated by Linyphiidae and Amaurobiidae with Coelotes terrestris (Wider 1834) being the dominant species, whereas forest floor samples comprised mostly Hahniidae and Linyphiidae with Hahnia pusilla C.L. Koch 1841 being most abundant. Most species and individuals were web builders. Hunting spiders were collected rarely, even in pitfall traps (7% of all individuals).

Mean species richness of spiders in pitfall trap catches was highest in DL 2 and significantly lower in DL 1 (F 2, 45 = 2.83; P = 0.012; Fig. 3a). The plot effect within the levels (F 6, 45 = 2.39; P = 0.043) was not relevant and did not affect the results for the diversity levels. The mean number of all—adult and juvenile—spiders (F 2, 45 = 15.54; P < 0.001) and of adult spiders (F 2, 45 = 13.31; P < 0.001) was significantly higher in DL 1 than in DL 3, with activity of all spiders decreasing steadily with increasing stand diversity (Fig. 3b and c). Plot effects (F 6, 45 = 3.10; P = 0.013 for all spiders and F 6, 45 = 3.95; P = 0.003 for adults) were weak and did not influence mean spider numbers. Temporal changes in numbers of adult spiders caught in pitfall traps were similar for DL 1 and 2, with two distinct peaks of activity in June/July and in September, whereas in DL 3 the first peak was more or less missing (Fig. 4).

Mean values (±1 SE) of spider species richness (a), number of all spiders (b) and number of adult spiders (c) per pitfall trap for the three tree species diversity levels (DL 1, DL 2 and DL 3, see Fig. 1) for the whole sampling period. Bars with different letters show significant differences between diversity levels at P = 0.05 using ANOVA and Tukey’s post hoc test

Temporal changes in the number of adult spiders (mean values) caught per pitfall trap for the three tree species diversity levels (DL 1, DL 2 and DL 3, see Figure 1) during the trapping period

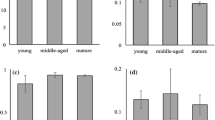

Species richness in forest floor samples differed significantly on two (May and August) of the three sampling dates, being highest in DL 2 and lowest in DL 1 (F 2, 45 = 7.53; P = 0.002 and F 2, 45 = 5.84; P = 0.006; Fig. 5a–c). Differences in total abundance for all spiders were only significant in May (F 2, 45 = 4.61; P = 0.015; Fig. 5d–f), whereas numbers of adults were markedly higher in DL 2 than in DL 1 on all sampling dates (May: F 2, 45 = 10.24; P < 0.001, August: F 2, 45 = 8.86; P < 0.001 and November: F 2, 45 = 4.95; P = 0.011). DL 3 was intermediate, with abundance being high in May and November and low in August (Fig. 5g–i). Weak and negligible plot effects appeared in May for species richness (F 6, 45 = 4.0; P = 0.003) and for abundance of all individuals (F 6, 45 = 2.53; P = 0.034).

Mean values (±1 SE) of spider species richness (a–c), abundance of all spiders (d–f) and abundance of adult spiders (g–i) per forest floor sample for the three tree species diversity levels (DL 1, DL 2 and DL 3, see Fig. 1) on three sampling dates (May, August and November). Bars with different letters show significant differences between diversity levels at P = 0.05 using ANOVA and Tukey’s post hoc test. ANOVAs performed with log-transformed values, but means of untransformed values are shown

The Shannon-Wiener index for pitfall trap catches increased with stand diversity from DL 1 to DL 3 due to increasing evenness (Table 2). Forest floor sample data rendered opposite results with decreasing diversity from DL 1 to DL 3 on all three sampling dates due to decreasing evenness (Table 2).

Community structure

The ordination of the pitfall trap dataset revealed differences in community structure between plots rather than between diversity levels (Fig. 6). Differentiation was significant mainly along the first axis, the eigenvalue of the second axis being very low. The two plots DL 3a and DL 3b, located at the same study site (cf. Fig. 1), were distinct from the other seven plots, which formed a rather homogeneous group without clear separation of the plots.

PCA ordination plot for spider data (whole trapping period) from pitfall traps of the nine studied plots (DL 1a-DL 3c, see Fig. 1). Data were log-transformed. Eigenvalues: first axis (horizontal) = 0.277, second axis (vertical) = 0.148. Cumulative percentage variance of species data for both axes: 42.5%. Only species with >3 individuals were included into the analysis. Circles and squares each represent a trap. Triangles represent species. Abbreviations are names of species: Agroeca brunnea (Blackwall 1833), Agyneta ramosa Jackson 1912, Apostenus fuscus Westring 1851, Centromerus leruthi Fage 1833, Centromerus sylvaticus (Blackw. 1841), Ceratinella brevis (Wider 1834), Cicurina cicur (Fabricius 1793), Clubiona terrestris Westr. 1851, Coelotes inermis (L. Koch 1855), Coelotes terrestris (Wider 1834), Cybaeus angustiarum L. Koch 1868, Dicymbium tibiale (Blackw. 1836), Diplocephalus latifrons (O.P.-Cambr. 1863), Diplocephalus picinus (Blackw. 1841), Diplostyla concolor (Wider 1834), Gonatium rubellum (Blackw. 1851), Hahnia pusilla C.L. Koch 1841, Harpactea lepida (C.L. Koch 1838), Histopona torpida (C.L. Koch 1834), Lepthyphantes minutus (Blackw. 1833), Linyphia hortensis Sundevall 1830, Macrargus rufus (Wider 1834), Micrargus herbigradus (Blackw. 1854), Microneta viaria (Blackw. 1841), Ozyptila trux (Blackw. 1847), Palliduphantes pallidus (O.P.-Cambr. 1871), Panamomops mengei Simon 1926, Robertus lividus (Blackw. 1836), Saloca diceros (O.P.-Cambr. 1871), Tapinocyba insecta (L. Koch 1869), Tegenaria silvestris L. Koch 1872, Tenuiphantes cristatus (Menge 1866), Tenuiphantes mengei Kulczynski 1887, Tenuiphantes tenebricola (Wider 1834), Tenuiphantes zimmermanni Bertkau 1890, Walckenaeria atrotibialis O.P.-Cambr. 1878, Walckenaeria corniculans (O.P.-Cambr. 1851), Walckenaeria cucullata (C.L. Koch 1837), Walckenaeria cuspidata (Blackw. 1833), Walckenaeria dysderoides (Wider 1834), Walckenaeria mitrata (Menge 1868), Walckenaeria obtusa Blackw. 1836, Xysticus lanio C.L. Koch 1824, Zora spinimana (Sundev. 1833)

While many spider species were common on most plots, there was a group of spiders accounting for the differences in spider community structure. The species Diplocephalus picinus (Blackwall 1841) and Hahnia pusilla were important for DL 1, the former being abundant especially on plot DL 1c, the latter being almost totally absent from all DL 1 plots. Species such as Diplostyla concolor (Wider 1834), Tenuiphantes cristatus (Menge 1866) and Tenuiphantes tenebricola (Wider 1834) were highly associated with plots DL 3a and DL 3b, whereas other species, especially Harpactea lepida (C.L. Koch 1838), Histopona torpida (C.L. Koch 1834), Saloca diceros (O.P.-Cambridge 1871) and Walckenaeria corniculans (O.P.-Cambridge 1851) were less frequent or missing on these plots. These differences were highly significant, as shown by ANOVA comparing the nine plots (Table 3). Comparison between diversity levels yielded considerable plot effects within DL 3 for these species. Thus, the statistical analysis of the nine plots was preferred to a comparison of the three diversity levels, the latter obscuring significant differences within these levels.

Spider communities in the forest floor were even more homogeneous across the diversity gradient than spider assemblages in pitfall traps. Thus, only the ordination of November data is shown, where eigenvalues were largest (Fig. 7). Community structure of forest floor samples was strongly affected by the distribution of the dominant species Hahnia pusilla and Saloca diceros. The almost entire absence of H. pusilla in the DL 1 plots caused a separation of these plots from most of the DL 2 and DL 3 samples, but high variation of samples within all plots obscured this differentiation to a certain extent. However, mean densities of the highly abundant H. pusilla were significantly lower in DL 1 compared to DL 2 and DL 3 on all sampling dates without any plot effects (May: F 2, 45 = 28.21; P < 0.001, August: F 2, 45 = 14.76; P < 0.001 and November: F 2, 45 = 24.31; P < 0.001). Comparable to pitfall trap data, the second most abundant species, S. diceros, was missing in plots DL 3a and DL 3b, while being highly abundant on the other plots. However, these differences were not statistically significant because of the high variation within plots (Table 4).

PCA ordination plot for spider data (November samples) from forest floor sampling of the nine studied plots (DL 1a-DL 3c, see Fig. 1). Data were log-transformed. Eigenvalues: first axis (horizontal) = 0.446, second axis (vertical) = 0.205. Cumulative percentage variance of species data for both axes: 65%. Circles and squares each represent a trap. Triangles represent species. Additional abbreviations to those listed in Fig. 6: Eperigone trilobata (Emerson 1882) and Robertus neglectus (O.P.-Cambr. 1871)

Influence of environmental parameters

For forest floor samples, eigenvalues of PCA (cf. Fig. 7) and RDA (first axis 0.230, second axis 0.032) as well as the distribution of plots within the ordinations differed considerably, even though Monte Carlo testing of axes was significant (P = 0.004). Thus, the correlations between ordination of spider communities and environmental variables in the RDA do not adequately explain community patterns and the RDA graph is not presented here.

RDA for pitfall trap data showed highly negative correlations between community structure of DL 3a and DL 3b and litter depth, amount of beech litter, and Collembolan densities, as well as positive correlations with the amount of lime litter and percentage of herb cover (Fig. 8). In this case eigenvalues of RDA and PCA differed only marginally confirming the significance of the Monte Carlo permutation test, thus indicating good correlations between environmental variables and community patterns.

RDA ordination plot for spider communities (pitfall trap catches) of the nine studied plots (DL 1a-DL 3c, shown as centroids = weighted means of spider data) and correlated environmental variables (arrows). Data log-transformed. Eigenvalues: first axis (horizontal) = 0.239, second axis (vertical) = 0.059. Cumulative percentage variance of species data for both axes: 29.8%. Only species with >3 individuals were included into the analysis (Species are not shown in ordination plot). Monte Carlo permutation test: first axis F = 13.8 and P = 0.002; all axes F = 3.1 and P = 0.002

Since species richness and total spider numbers of the plots could not be included into RDA, separate correlations were performed for the 54 pitfall traps/forest floor samples. There was a highly significant positive correlation between species numbers and litter diversity (Shannon-Wiener index; ρ = 0.47, P < 0.001) for pitfall trap data. Total number of individuals was correlated negatively with litter diversity (ρ = −0.46; P < 0.001) and herb cover (ρ = −0.54; P < 0.001) and positively with litter depth (ρ = 0.58; P < 0.001) and Collembolan densities (ρ = 0.53; P < 0.001). There was no significant correlation for species richness of forest floor samples with any of the above environmental variables. Only total spider abundance correlated with the amount of lime litter in May (ρ = 0.42; P = 0.001), but this effect disappeared completely in August and November.

Discussion

Spider diversity and numbers

With both methods, pitfall trapping [methodological constraints having been extensively discussed by Adis (1979), Churchill and Arthur (1999), Wagner et al. (2003) and many others] and quantitative forest floor sampling, mean species richness was highest in medium diverse (DL 2) and lowest in least diverse forest stands (DL 1). Mean abundance of spiders in forest floor samples exhibited the same pattern, being more pronounced for adults than for total numbers including juveniles, while activity in pitfall traps decreased from DL 1 to DL 3. Thus, except for the latter trend, there was no clear gradient attributable to increasing stand diversity. Rather, the results indicate a strong influence of factors that appear to be modified by the relative dominance of beech or lime rather than by tree species diversity itself, as will be discussed below. There are no studies directly comparable to this analysis, considering tree species diversity in deciduous forests. However, there is a plentitude of descriptive and experimental studies in single forest stands dealing with influencing variables on spider diversity and abundance, which can be used to derive general patterns determining the composition of the spider fauna in forests.

In the present study, the spider fauna presumably was affected to a large extent by litter depth and herb cover, although no definite conclusions can be drawn since no manipulative experiments were done. Litter depth is dependent on the dominant tree species, with beech being decomposed much more slowly than ash or lime, resulting in a constantly deep litter layer (Swift et al. 1979; Dunger 1983).

High species numbers in DL 2 may be ascribed to the beneficial combination of litter depth and herb cover. Both factors are known to promote spider species richness in deciduous forests (Uetz 1976 and 1990; Stevenson and Dindal 1982; Docherty and Leather 1997; Bird et al. 2000; Willett 2001). In DL 1 the herb layer was only poorly developed and in DL 3 the litter layer was sparsely developed due to high earthworm activity (Cesarz et al. 2007), while in DL 2 both herb and litter layer were well developed, enabling the occurrence of both litter- and ground-vegetation inhabiting species. Whereas Uetz (1979 and 1990) found litter depth to be the all-important factor influencing wandering spiders, in the present study herb cover appears to have a major influence as well, since mostly web-building spiders were recorded. These can use the lower parts of plants for web construction (Standen 2000; Oxbrough et al. 2005).

Mean spider activity strongly correlated with litter depth, decreasing from DL 1 to DL 3. As with species richness, this factor is known to affect spider activity (pitfall traps) as well as spider abundance (forest floor samples) by increasing interstitial space and thus available habitat within the litter (Bultman and Uetz 1982; Stippich 1989; Uetz 1990; Irmler 2005). Spider numbers also correlated with prey densities (Collembola), another influencing factor which can be separated from litter depth only experimentally (Chen and Wise 1999). There is no direct explanation for the deviating pattern in spider abundance of forest floor samples. High values in DL 2 and low values in DL 1 were rather unexpected. Possibly, this pattern is caused by the absence of the otherwise highly abundant species Hahnia pusilla from DL 1. According to Hänggi et al. (1995), this species is rare in pure beech forests and more numerous in mixed deciduous forests. This is supported by studies from beech forests on acidic soil with a deep litter layer, where this species was very rare (Albert 1976; Dumpert and Platen 1985; Roß-Nickoll 2000). Still, the underlying factors causing low spider abundance in DL 1, despite high availability of habitat and prey, require closer experimental investigation.

Soil moisture and humidity, often cited as important environmental factors for spider diversity and abundance (Abraham 1983; De Bakker et al 2001), were not crucial in this study as they were not distinctly different between diversity levels or between plots.

Diversity indices are often considered to be a more indicative diversity measure than mere species richness (Magurran 2004). The results for Shannon-Wiener indices differed from those for species richness. However, they also differed between the two sampling methods, with the Shannon-Wiener index increasing with stand diversity for pitfall trap catches and decreasing for forest floor samples. Apart from the low number of adults in the forest floor samples, this is probably a result of sampling different components of the soil, litter and epigeic fauna by using these two methods (see Hutha 1971). Thus, for diversity and equitability of assemblages of epigeic spiders in pitfall traps, herb cover might have been an important factor, as was also found by Docherty and Leather (1997), Bird et al. (2000) and Willett (2001). Spiders from forest floor samples might be more affected by the litter layer. Uetz (1975) assumes that evenness of spiders on the forest floor is enhanced by reduction of inter- and intraspecific predation in deep litter resulting in higher diversity.

Community structure

Pitfall trap spider assemblages did not distinctly differ between diversity levels. Only few species were especially associated with plots of DL 1 (Diplocephalus picinus and Histopona torpida) or were missing there (Hahnia pusilla). Altogether, communities of the three diversity levels were characterized by high similarity of species composition and dominance structure (see also Luczak 1963; Hutha 1965; Whitehouse et al. 2002). However, differences of community composition were present at the study site or plot level. Thus, variation of environmental factors between plots was more important than variation caused by actual tree species diversity, as was already discussed for species richness. This is seen clearly by the different community structures of plots DL 3a and DL 3b, which is probably due to the high dominance of lime or rather lower proportion of beech compared to the other plots. This results in specific modifications of environmental factors such as strong reduction of litter during the summer months, which is caused by the high palatability of lime litter for saprophagous invertebrates such as earthworms, diplopods and isopods. All these animal taxa were highly abundant in DL 3a and DL 3b (Cesarz et al. 2007; N. Fahrenholz, unpublished data). Tenuiphantes tenebricola, one of the differentiating spider species, was found to prefer a sparse litter layer and an ample herb layer (A. Sührig, unpublished data), typical for these two plots. Despite a lack of detailed information on habitat preferences of Diplostyla concolor, Tenuiphantes cristatus and Diplocephalus latifrons (O.P.-Cambridge 1863), there is evidence that they are influenced by factors similar to those important for T. tenebricola (Beyer 1972; Heimer and Hiebsch 1982; Bauchhenss et al. 1987; Höfer 1989; Hänggi et al. 1995). Those species being rare or absent from these two plots (Histopona torpida, Harpactea lepida, Saloca diceros and Walckenaeria corniculans) are known to prefer forest sites with a deep and continuous litter layer (Stippich 1986; A. Sührig, unpublished data). Avoidance of DL 3a and DL 3b by these mostly spring to summer active species and low numbers on DL 3c also explain the generally low spider activity in DL 3 in June/July.

Apart from differences in dominating tree species, there was also a clear effect of the vicinity of plots on spider community composition due to clustering within study sites. Centroids (weighted means) of neighbouring plots were also situated close to each other in multivariate ordination (see map, Fig. 1 and RDA, Fig. 8). Increased and wide-ranging activity of species caught in pitfall traps during maturity, radiating into adjacent plots, probably attenuated the impact of differences in environmental characteristics between diversity levels. Proximity of plots resulting in higher similarity of plots despite rather different habitat features was also observed by Luczak (1963), Heublein (1983), Hofmann (1986), Irmler and Heydemann (1988), Platen (1989) and Platen and Rademacher (2002).

As noted above, forest floor samples were characterized by low numbers of adult specimens leading to a high variation of samples within plots. Consequently, distinct patterns, as revealed with pitfall traps, were less obvious. Still, there were similar trends with the most abundant species Hahnia pusilla and Saloca diceros. Extreme dominance of the former species caused a more defined separation of mixed stands (DL 2 and DL 3) from pure beech stands (DL 1) than found for pitfall trap assemblages, which were dominated by a higher number of species common in both pure and mixed stands. Once again, this demonstrates the differences in the sampling procedures of the two methods.

RDA of forest floor samples was even more strongly affected by the above-mentioned high variation of samples and indistinct separation of plots. Though the correlations between environmental factors and spiders did not adequately explain differentiation of plots, it can be assumed that the determining factors influencing pitfall trap spider assemblages are important for forest floor sample spiders, too, as was found by Hutha (1971), Stippich (1989) and Irmler (2005).

Conclusions

No consistent general relationship between increasing tree species diversity and patterns of diversity and abundance of spider communities emerged. The diversity indices for the spider fauna based on data obtained by the two sampling methods correlated differently with the diversity of the forest stands, thus hampering a coherent interpretation. Diversification of forest stands can affect patterns of species richness and spider numbers as compared to pure beech stands. However, underlying structuring factors are not necessarily dependent on stand diversity. Rather, results indicate a strong influence of the dominating tree species (beech or lime) and its specific modifications of habitat characteristics. Similar trends were also found for higher strata (A. Schuldt, unpublished data). Still, the impact of actual tree species diversity on the multi-factorial complex determining species richness and abundance of the spider fauna cannot ultimately be separated from effects of the dominance of certain tree species. Both variables are directly linked to each other in the present study, impeding evaluation of their relative importance and demanding further experimental studies.

References

Abraham BJ (1983) Spatial and temporal patterns in a sagebrush steppe spider community (Arachnida, Araneae). J Arachnol 11:31–50

Adis J (1979) Problems of interpreting arthropod sampling with pitfall traps. Zool Anz 202:177–184

Ahrns C, Hofmann G (1998) Vegetationsdynamik und Florenwandel im ehemaligen mitteldeutschen Waldschutzgebiet „Hainich” im Intervall 1963–1995. Hercynia 31:33–64

Albert R (1976) Struktur und Dynamik der Spinnenpopulationen in Buchenwäldern des Solling. Verh Ges Ökol 1976:83–91

Bauchhenss E, Dehler W, Scholl G (1987) Bodenspinnen aus dem Raum Veldensteiner Forst (Naturpark „Fränkische Schweiz/Veldensteiner Forst”). Ber Naturwiss Ges Bayreuth 19:7–44

Beyer R (1972) Zur Fauna der Laubstreu einiger Waldstandorte im Naturschutzgebiet „Prinzenschneise” bei Weimar. Arch Natursch Landschaftsforsch 12:203–229

Bird S, Coulson RN, Crossley DA (2000) Impacts of silvicultural practices on soil and litter arthropod diversity in a Texas pine plantation. Forest Ecol Manage 131:65–80

Bultman TL, Uetz GW (1982) Abundance and community structure of forest floor spiders following litter manipulation. Oecologia 55:34–41

Cesarz S, Fahrenholz N, Migge-Kleian S, Platner C, Schaefer M (2007) Earthworm communities in relation to tree diversity in a deciduous forest. Eur J Soil Biol (2007). doi:10.1016/j.ejsobi.2007.08.003

Chen B, Wise DH (1999) Bottom-up limitation of predaceous arthropods in a detritus-based terrestrial food web. Ecology 80:761–772

Churchill TB, Arthur JM (1999) Measuring spider richness: effects of different sampling methods and spatial and temporal scales. J Insect Conserv 3:287–295

De Bakker D, Maelfait JP, Baert L, Hendrickx F (2001) Spider diversity and community structure in the forest of Ename (Eastern Flanders, Belgium). Bull Inst Roy Sci Nat Bel Entomol 71:45–54

De Ruiter PC, Griffiths B, Moore JC (2002) Biodiversity and stability in soil ecosystems: patterns, processes and the effects of disturbance. In: Loreau M, Naeem S, Inchausti P (eds) Biodiversity and ecosystem functioning. Synthesis and perspectives. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 102–113

Docherty M, Leather SR (1997) Structure and abundance of arachnid communities in Scots and lodgepole pine plantations. Forest Ecol Manage 95:197–207

Dumpert K, Platen R (1985) Zur Biologie eines Buchenwaldbodens, 4. Die Spinnenfauna. Carolinea 42:75–106

Dunger W (1983) Tiere im Boden, 3rd edn. A. Ziemsen, Wittenberg

Finke DL, Denno RF (2005) Predator diversity and the functioning of ecosystems: the role of intraguild predation in dampening trophic cascades. Ecol Lett 8:1299–1306

Fitter AH, Gilligan CA, Hollingworth K, Kleczkowski A, Twyman RM, Pitchford JW, The members of the NERC Soil Biodiversity Programme (2005) Biodiversity and ecosystem function in soil. Funct Ecol 19:369–377

Gartner TB, Cardon ZG (2004) Decomposition dynamics in mixed-species leaf litter. Oikos 104:230–246

Gurdebeke S, De Bakker D, Vanlanduyt N, Maelfait JP (2003) Plans for a large regional forest in eastern Flanders (Belgium): assessment of spider diversity and community structure in the current forest remnants. Biodivers Conserv 12:1883–1900

Hänggi A, Stöckli E, Nentwig W (1995) Habitats of Central European spiders. Misc Faun Helv 4:1–459

Hatley CL, MacMahon JA (1980) Spider community organization: seasonal variation in the role of vegetation architecture. Environ Entomol 9:632–639

Heimer S, Hiebsch H (1982) Beitrag zur Spinnenfauna der Naturschutzgebiete Großer und Kleiner Hakel unter Einbeziehung angrenzender Waldgebiete. Hercynia 19:74–84

Heublein D (1983) Räumliche Verteilung, Biotoppräferenzen und kleinräumige Wanderungen der epigäischen Spinnenfauna eines Wald-Wiesen-Ökotons; ein Beitrag zum Thema „Randeffekt”. Zool Jb Syst 110:473–519

Höfer H (1989) Beiträge zur Wirbellosenfauna der Ulmer Region: 1. Spinnen (Arachnida: Araneae). Mitt d Ver f Naturwiss u Math Ulm (Donau) 35:157–176

Hofmann I (1986) Die Webspinnenfauna (Araneae) unterschiedlicher Waldstandorte im Nordhessischen Bergland. Berliner Geogr Abh 41:183–200

Hooper DU, Chapin FS, Ewel JJ, Hector A, Inchaustl P, Lavorel S, Lawton JH, Lodge DM, Loreau M, Naeem S, Schmid B, Setälä H, Symstad AJ, Vandermeer J, Wardle DA (2005) Effects of biodiversity on ecosystem functioning: a consensus of current knowledge. Ecol Monogr 75:3–35

Hunter MD, Adl S, Pringle CM, Coleman DC (2003) Relative effects of macroinvertebrates and habitat on the chemistry of litter during decomposition. Pedobiologia 47:101–115

Hutha V (1965) Ecology of spiders in the soil and litter of Finnish forests. Ann Zool Fenn 2:260–308

Hutha V (1971) Succession in the spider communities of the forest floor after clear-cutting and prescribed burning. Ann Zool Fenn 8:483–542

Irmler U (2005) Long-term fluctuations on the spider populations (Araneida) in a northern German woodland. Faun-ökol Mitt 8:337–352

Irmler U, Heydemann B (1988) Die Spinnenfauna des Bodens schleswig-holsteinischer Waldökosysteme. Faun-ökol Mitt 6:61–85

Jocque R (1973) The spider fauna of adjacent woodland areas with different humus types. Biol Jaarb Dodonaea 41:153–178

Kajak A (1995) The role of soil predators in decomposition processes. Eur J Entomol 92:573–580

Kempson D, Lloyd M, Ghelardi R (1963) A new extractor for woodland litter. Pedobiologia 3:1–21

Lawrence KL, Wise DH (2004) Unexpected indirect effect of spiders on the rate of litter disappearance in a deciduous forest. Pedobiologia 48:149–157

Lensing JR, Todd S, Wise DH (2005) The impact of altered precipitation on spatial stratification and activity-densities of springtails (Collembola) and spiders (Araneae). Ecol Entomol 30:194–200

Luczak J (1963) Differences in the structure of communities of web spiders in one type of environment (young pine forest). Ekol Pol A 6:159–219

Macfadyen A (1961) Improved funnel-type extractors for soil arthropods. J Anim Ecol 30:171–184

Magurran AE (2004) Measuring biological diversity. Blackwell Science, Malden, MA

Mikola J, Bardgett RD, Hedlund K (2002) Biodiversity, ecosystem functioning and soil decomposer food webs. In: Loreau M, Naeem S, Inchausti P (eds) Biodiversity and ecosystem functioning. Synthesis and perspectives. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 169–180

Mölder A, Bernhardt-Römermann M, Schmidt W (2006) Forest ecosystem research in Hainich National Park (Thuringia): First results on flora and vegetation in stands with contrasting tree species diversity. Waldoekologie online 3:83–99

Mönninghoff W (1998) Nationalpark Hainich. VEBU, Berlin

Niemelä J, Haila Y, Punttila P (1996) The importance of small-scale heterogeneity in boreal forests: variation in diversity in the forest-floor invertebrates across the succession gradient. Ecography 19:352–368

Oxbrough AG, Gittings T, O’Halloran J, Giller PS, Smith GF (2005) Structural indicators of spider communities across the forest plantation cycle. For Ecol Manage 212:171–183

Platen R (1989) Struktur der Spinnen- und Laufkäferfauna (Arach.: Araneida, Col.: Carabidae) anthropogen beeinflusster Moorstandorte in Berlin (West). Taxonomische, räumliche und zeitliche Aspekte. Dissertation, Technical University of Berlin

Platen R, Rademacher J (2002) Charakterisierung von Kiefernwäldern und – forsten durch Spinnen in den Bundesländern Berlin und Brandenburg. Natursch Landschaftspfl Bbg 11:243–251

Riechert SE, Lawrence K (1997) Test for predation effects of single versus multiple species of generalist predators: spiders and their insect prey. Entomol Exp Appl 84:147–155

Roß-Nickoll M (2000) Biozönologische Gradientenanalyse von Wald-, Hecken- und Parkstandorten der Stadt Aachen. Verteilungsmuster von Phyto-, Carabido- und Araneozönosen. Publikationsreihe des interdisziplinären Umwelt-Forums der RWTH Aachen 11:1–148

Schaefer M (1991) The animal community: diversity and resources. In: Röhrig E, Ulrich W (eds) Ecosystems of the world 7. Temperate deciduous forests. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 51–120

Schauermann J (1982) Verbesserte Extraktion der terrestrischen Bodenfauna im Vielfachgerät modifiziert nach Kempson und Macfadyen. Mitt SFB 135:47–50

Scheiner SM, Gurevitch J (eds) (1993) Design and analysis of ecological experiments. Chapman & Hall, New York

Scherer-Lorenzen M, Körner Ch, Schulze E-D (2005) Forest diversity and function. Temperate and boreal systems. Ecological Studies 176. Springer, Berlin

Seidel G (eds) (1995) Geologie von Thüringen. Schweizerbart, Stuttgart

Setälä H (2005) Does biological complexity relate to functional attributes of soil food webs? In: De Ruiter P, Wolters V, Moore JC (eds) Dynamic food webs: multispecies assemblages, ecosystem development, and environmental change. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 308–320

Standen V (2000) The adequacy of collecting techniques for estimating species richness of grassland invertebrates. J Appl Ecol 37:884–893

Stevenson BG, Dindal DL (1982) Effect of leaf shape on forest litter spiders: community organization and microhabitat selection of immature Enoplognatha ovata (Clerck)(Theridiidae). J Arachol 10:165–178

Stippich G (1986) Die Spinnenfauna (Arachnida: Araneida) eines Kalkbuchenwaldes: Bedeutung von Habitatstruktur und Nahrung. Dissertation, University of Göttingen

Stippich G (1989) Die Bedeutung von natürlichen und künstlichen Strukturelementen für die Besiedlung des Waldbodens durch Spinnen (Zur Funktion der Fauna in einem Mullbuchenwald 14). Verh Ges Ökol 17:293–298

Sührig A (1997) Die Spinnenfauna des Göttinger Waldes (Arachnida: Araneida). Göttinger Naturkdl Schr 4:117–135

Swift MJ, Heal OW, Anderson JM (1979) Decomposition in terrestrial ecosystems. Blackwell, Oxford

Ter Braak CJF, Šmilauer P (2002) CANOCO Reference Manual and CanoDraw for Windows User’s Guide: software for canonical community ordination (version 4.5). Microcomputer Power, Ithaca

Uetz GW (1975) Temporal and spatial variation in species diversity of wandering spiders (Araneae) in deciduous forest litter. Environ Entomol 4:719–724

Uetz GW (1976) Gradient analysis of spider communities in a streamside forest. Oecologia 22:373–385

Uetz GW (1979) The influence of variation in litter habitats on spider communities. Oecologia 40:29–42

Uetz GW (1990) Habitat structure and spider foraging. In: Bell SS, McCoy ED, Mushinsky HR (eds) Habitat structure. The physical arrangement of objects in space. Chapman & Hall, London, pp 325–348

Unsicker SB, Baer N, Kahmen A, Wagner M, Buchmann N, Weisser WW (2006) Invertebrate herbivory along a gradient of plant species diversity in extensively managed grasslands. Oecologia 150:233–246

Wagner JD, Toft S, Wise DH (2003) Spatial stratification in litter depth by forest-floor spiders. J Arachnol 31:28–39

Wardle DA (2006) The influence of biotic interactions on soil biodiversity. Ecol Lett 9:870–886

Weidemann G (1976) Struktur der Zoozönose im Buchenwald-Ökosystem des Solling. Verh Ges Ökol 1976:59–74

Whitehouse MEA, Shochat E, Shachak M, Lubin Y (2002) The influence of scale and patchiness on spider diversity in a semi-arid environment. Ecography 25:395–404

Willett TR (2001) Spiders and other arthropods as indicators in old-growth versus logged redwood stands. Restor Ecol 9:410–420

Wise DH (2004) Wandering spiders limit densities of a major microbi-detritivore in the forest-floor food web. Pedobiologia 48:181–188

Wise DH, Chen B (1999) Impact of intraguild predators on survival of a forest-floor wolf spider. Oecologia 121:129–137

Wise DH, Snyder WE, Tuntibunpakul P, Halaj J (1999) Spiders in decomposition food webs of agroecosystems: theory and evidence. J Arachnol 27:363–370

Acknowledgements

The study was part of a larger project of the Research Training Group “The role of biodiversity for biochemical cycles and biotic interactions in temperate deciduous forests”, funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG). We thank the colleagues from the DFG Research Training Group 1086 supporting our studies with data, especially Karl-Maximilian Daenner, Anja Guckland and Andreas Mölder, and the administration of the Hainich National Park for their assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Schuldt, A., Fahrenholz, N., Brauns, M. et al. Communities of ground-living spiders in deciduous forests: Does tree species diversity matter?. Biodivers Conserv 17, 1267–1284 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-008-9330-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-008-9330-7