Abstract

Only one study has examined bidirectional causality between sexual minority status (having same-sex attraction) and psychological distress. We combined twin and genomic data from 8700 to 9700 participants in the UK Twins Early Development Study cohort at ≈21 years to replicate and extend these bidirectional causal effects using separate unidirectional Mendelian Randomization-Direction of Causation models. We further modified these models to separately investigate sex differences, moderation by childhood factors (retrospectively-assessed early-life adversity and prospectively-assessed childhood gender nonconformity), and mediation by victimization. All analyses were carried out in OpenMx in R. Same-sex attraction causally influenced psychological distress with significant reverse causation (beta = 0.19 and 0.17; 95% CIs = 0.09, 0.29 and 0.08, 0.25 respectively) and no significant sex differences. The same-sex attraction → psychological distress causal path was partly mediated by victimization (12.5%) while the reverse causal path was attenuated by higher childhood gender nonconformity (moderation coefficient = −0.09, 95% CI: −0.13, −0.04).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

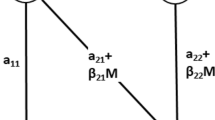

Psychological distress (depressive and anxiety symptoms) is significantly higher among individuals who are sexually attracted to people of the same sex (including those who identify as being lesbian, gay or bisexual) compared to those who are exclusively heterosexual (King et al., 2008; Plöderl & Tremblay, 2015; Semlyen et al., 2016). Minority stress theory attributes these mental health disparities to the stressful consequences of having a sexual minority identity (Meyer, 2003) which, in turn, is based on same-sex sexual attraction (Bailey et al., 2016). Specific minority stress factors include experiences of discrimination or victimization, concealment of sexual orientation and internalized sexuality-related stigma (Meyer, 2003). Related processes include rejection sensitivity (Feinstein, 2020), emotional dysregulation (Hatzenbuehler, 2009) and excessive rumination (Timmins et al., 2020). Some of these minority stressors (e.g., sexuality-related discrimination and internalized stigma, and concealment) are predominantly experienced by same-sex attracted individuals. Apart from these, sexual minority individuals may further experience intangible sexuality-related stresses, which also contribute to the observed health disparities but are difficult to measure (Schwartz & Meyer, 2010). Hence, consistent with previous theory and research (Oginni et al., 2022a; Schwartz et al., 2010), in the present study, sexual minority status (e.g., having same-sex sexual attraction) is regarded as an index of measurable and unmeasurable sexuality-related stress (Fig. 1).

Schematic illustration of the bidirectional relationships between same-sex attraction and psychological distress (a) and proposed mediation of these relationships by discriminatory experiences (b); a component of minority stress (Meyer, 2003). Note: a depicts bidirectional (i.e., forward and reverse) causal relationships between same-sex attraction (as an index of sexuality-related stress; Schwartz and Meyer, 2010) and increased psychological distress but without a specific mechanism (e.g., as demonstrated by Oginni et al., 2022a). This relationship may be further decomposed into (i) a mediation of the ‘forward’ causal effect of same-sex attraction on psychological distress by discriminatory experiences, and (ii) a reciprocal causal relationship between discriminatory experiences and psychological distress (b)

However, the links between minority stress and mental health disparities among same-sex attracted individuals is mostly cross-sectional, which limits causal inference (Bailey, 2020). Thus, while there is a robust cross-sectional evidence base (Dürrbaum & Sattler, 2020), this is not sufficient to inform intervention design. Furthermore, the few studies that utilize a longitudinal design only test for prospective associations rather than the direction of causality (e.g., Bränström, 2017). In contrast, studies that have investigated causality tend to utilize samples comprising only sexual minority participants (Rosario et al., 2002). Although this within-group analysis allows the investigation of the effects of minority stressors which are unique to same-sex attracted individuals, the absence of a comparison heterosexual group limits the extent to which the findings are indicative of health disparities between same-sex attracted and heterosexual individuals (Meyer, 2010; Schwartz & Meyer, 2010). A superior approach would be to investigate stressors in both same-sex attracted and heterosexual samples and determine the extents to which they account for observed health disparities.

Recently, an alternative approach was used to provide evidence for bidirectional causal relationships between sexual minority stress (indexed by sexual minority status) and psychological distress (Oginni et al., 2022a). Specifically, the authors used a model that combines the Direction of Causation twin model with Mendelian Randomisation using polygenic scores as instruments to determine causality—the Mendelian Randomisation-Direction of Causation (MRDoC) model (Minică et al., 2018). The advantage of the MRDoC model is that it enables the relaxation of certain assumptions of each individual method (Minică et al., 2018), which in turn leads to less-biased estimates of causal path coefficients (Minică et al., 2020). More details of this analytic approach are provided in the Methods section.

Previous research indicates that the disparity in depressive and anxiety disorders among sexual minority compared to heterosexual individuals is greater among males compared to females (King et al., 2008). Furthermore, there is evidence that early-life adversities and childhood gender nonconformity moderate the cross-sectional phenotypic and genetic and environmental correlations between sexual minority status and depressive and/or anxiety symptoms (D’Augelli et al., 2006; Oginni et al., 2022b). Finally, in explaining their finding of bidirectional causal effects (Oginni et al., 2022a), the authors speculated that the reverse causal effect indicated a positive feedback effect of psychological distress on sexual minority stress processes. However, this was not tested empirically, for example, by specifically testing mediation of the causal effects by measured minority stress factors (Fig. 1).

The objectives of the present study were therefore to: (i) use the MRDoC model to replicate the bidirectional causal associations between same-sex attraction (indexing sexuality-related distress) and psychological distress in a different twin sample; (ii) test sex differences in the proposed bidirectional causal relationships; (iii) test moderation of the causal paths by early-life adversities and childhood gender nonconformity; and (iv) test whether victimization (a proxy for minority stress) mediates these causal relationships.

We hypothesized that there would be bidirectional causal paths between same-sex attraction and psychological distress (i.e., stress associated with sexual minority status will cause psychological distress which can in turn potentiate the former), and that these effects would be stronger in men compared to women. Based on existing evidence (D’Augelli et al., 2006; Oginni et al., 2022b), we further hypothesized that the bidirectional causal links between same-sex attraction and psychological distress would be stronger at higher levels of early-life adversity and childhood gender nonconformity. Finally, we hypothesized that the causal path from same-sex attraction to psychological distress would be mediated by victimization but we were agnostic about mediation of the reverse causal path.

Methods

Sample

The sample comprised twin participants in the 21-year wave of the UK Twins Early Development Study (TEDS) cohort. Data were collected in two phases between June 2017 and February 2019. About 16,810 participating families were originally contacted; of these, both email and paper invitations were sent to 10,571 and 8611 families who respectively indicated willingness to participate in the first and second phases of data collection. In both phases, data were collected using either a mailed paper booklet, a mobile phone application, or a web-based platform as preferred by the participants. The final sample comprised 9697 and 8718 individuals (response rates of 45.9% and 50.6% respectively) from the first and second phases of data collection respectively, and these rates are comparable those from mailed surveys (Guo et al., 2016; Oginni et al., 2020). Further details of the recruitment and response rates are available from the TEDS website (https://www.teds.ac.uk/datadictionary/studies/21yr.htm) and from previous descriptions (Haworth et al., 2013; Rimfeld et al., 2019). Zygosity was assessed using a parent-reported measure of physical similarity during childhood; which, when compared to DNA testing, correctly identified 95% of twins (94% of monozygotic and 98% of dizygotic twins; Price et al., 2000).

Up to 285 individuals were excluded due to unknown zygosity and missing essential background information. The number of participants with sufficient responses per variable ranged from 7915 to 9104 (Supplementary Table S1) corresponding to 91–96% of those who responded during phases 1 and 2 of data collection respectively. Ethical approval was granted by King’s College London’s ethics committee for the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Measures in main analyses

Same-sex attraction was used as an index for sexuality-related stress (Oginni et al., 2022a; Schwartz & Meyer, 2010). It was assessed using a single question about the sex of people to whom participants are sexually attracted, with responses including ‘Always male’, ‘Mostly male but sometimes female’, ‘Equally males and females’, ‘Mostly female but sometimes male’, and ‘Always female’. These were differentially recoded one to five to correspond to ‘Always opposite sex’, ‘Mostly opposite sex but sometimes same sex’, ‘Equally same and opposite sexes’, ‘Mostly same sex but sometimes opposite sex’ and ‘Always same sex’ in male and female participants. Thus, higher scores indicated greater same-sex attraction. Participants who selected either of two further responses: ‘Little or no sexual attraction’ and ‘Unsure or do not know’ were excluded from the analyses (n = 216) because the small sample size of this subgroup precludes meaningful comparisons. Same-sex attraction was specified as a liability threshold variable with four thresholds in which the observed categories are assumed to reflect imperfect thresholds of a latent normally-distributed liability to same-sex attraction (Kline, 2015; Rijsdijk & Sham, 2002).

Depressive symptoms were assessed using a shortened 8-item version of the Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (Angold et al., 1995). Each item rates the presence and severity of depressive symptoms over the prior two weeks via a three-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (Not at all) through 1 (Somewhat true) to 2 (True). Total scores were derived by summing the item responses whereby higher scores indicated more severe depressive symptoms. Cronbach’s alpha in the present study was 0.87 and continuous scores were used in analyses. Only participants who responded to at least 6 items were included in analyses.

Symptoms of Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) were assessed using the 10-item Severity Measure for Generalized Anxiety Disorder—Adult (Craske et al., 2013). The items rate the frequency of each symptom of GAD over the preceding week using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (Never) to 4 (All of the time). The responses were summed to derive a total score with higher scores indicating more severe GAD symptoms. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.91 and total scores were used in analyses. Only participants who responded to at least seven items were included in analyses.

Victimization was assessed using the 16-item victimization subscale of the Multidimensional peer-victimization scale (Mynard & Joseph, 2000). The items rate the frequency of physical, social, verbal and cyber bullying on a three-point Likert scale with responses including ‘Not at all’, ‘Once’, and ‘More than once’ coded 0, 1 and 2 respectively. The responses were summed with higher scores indicating higher victimization. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.87 and continuous scores were used in analyses. Only participants who responded to at least 12 items were included in analyses.

Early-life adverse experiences were retrospectively assessed using eight questions about physical and psychological abuse derived from items in the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (https://www.teds.ac.uk/datadictionary/studies/measures/21yr_ measures.htm). Each item was scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (Never) to 4 (Very often). Total scores were derived by summing the responses with higher scores indicating greater early-life adverse experiences. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.86 and continuous scores were used in analyses. Only participants who responded to at least 6 items were included in analyses.

Childhood gender nonconformity was prospectively assessed using the 24-item Pre-School Activities Inventory which was completed by the mothers when the twins were aged four years (Golombok & Rust, 1993). The questionnaire assesses stereotypical gender-specific play, activities and other characteristics. Responses are scored on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (very often). These were summed and transformed so that higher scores indicated higher male-typical behaviors. These scores were standardized, and scores for male participants multiplied by −1 so that higher scores in male and female participants were indicative of higher childhood gender nonconformity (Oginni et al., 2019). The Cronbach’s alpha for this questionnaire in the present study was 0.65 and continuous scores were used in analyses. Only participants who responded to at least 18 items were included in analyses.

For participants included in the analyses (those with item-level missingness ranging between 25% and 30% as described above), missing responses were prorated; furthermore, maximum likelihood estimation was used for structural equation modelling which is robust to missing data (Allison, 2003).

Covariates

Participants’ age and birth sex were ascertained using single questions asked during earlier waves of data collection.

Polygenic scores

Genotype data were collected at ages 12- and 16-years using cheek swab and saliva samples respectively. With these, polygenic scores were calculated for same-sex attraction,Footnote 1 depressive and anxiety symptoms as the weighted sum of the number of genome-wide trait-associated alleles weighted by effect sizes using the Bayesian-based LDpred (Vilhjálmsson et al., 2015). Effect sizes were derived from genome-wide association studies for same-sex behavior (Ganna et al., 2019), and depressive and anxiety symptoms (Howard et al., 2019; Purves et al., 2020). Further details of genomic data processing and polygenic score calculation are described in the supplementary material.

Latent factors

Four latent factors were specified to facilitate analyses as follows: Same-sex attraction (with the corresponding variable as its indicator), psychological distress (with depressive and anxiety symptoms as indicators), genetic propensity for same-sex attraction (with same-sex attraction polygenic scores as the indicator), and genetic propensity for psychological distress (with polygenic scores for depressive and anxiety symptoms as indicators).

Statistical analyses

Data preparation and summary statistics

Data cleaning and preliminary descriptive analyses were carried out using SPSS version 26 and STATA version SE 14.2. Subsequent analyses were carried out using OpenMx (Neale et al., 2016). The study variables were residualized to control for the covariates as is standard practice in twin modelling to reduce the potential inflation of the latent shared environmental effects (McGue & Bouchard, 1984). The residuals were further normalized to conform to parametric assumptions necessary for subsequent analyses.

Phenotypic correlations

Phenotypic factor correlations were estimated using maximum likelihood estimation and constraints applied to facilitate estimation of many correlations using a reduced set of statistics. Specifically, we constrained within-person correlations to be equal across birth order and zygosity; within-trait and cross-trait correlations were allowed to vary by zygosity while the latter were constrained to be symmetrical.

Multivariate genetic model fitting

Next, we used a Cholesky decomposition to parse the variances and covariance of the same-sex attraction and psychological distress latent factors, and the residual variances of their indicator variables into latent additive genetic (A) and shared (C) and individual-specific (E) environmental components. A influences index the sum of the effects of multiple genetic loci across the genome, C influences encompass environmental influences which make family members similar to one another and E influences include environmental factors which make family members different from one another including measurement error (Neale & Cardon, 2013; Rijsdijk & Sham, 2002). To estimate these components, the classical twin design assumes that monozygotic and dizygotic twin pairs raised together are 100% and 50% genetically similar respectively but are influenced by their shared environment to the same extent (Rijsdijk & Sham, 2002).

Mendelian randomization-direction of causation (MRDoC) models

We specified two separate MRDoC models to test whether same-sex attraction causally influenced psychological distress (MRDoC Model 1) and whether reverse causal influences also flowed from psychological distress to same-sex attraction (MRDoC Model 2). The MRDoC model combines Mendelian Randomization (MR) with the Direction of Causation (DoC) twin model which both use cross-sectional data to determine the direction of causation under specific conditions (Minică et al., 2018). The Direction of Causation model requires different patterns of variance component influences for each variable to test bidirectional causal effects (Heath et al., 1993). In contrast, Mendelian Randomization tests a unidirectional causal relationship by specifying individual genetic variants as instruments (Burgess & Thompson, 2011). To be valid, an instrument must be associated with the proposed exposure variable, independent of confounders and not independently associated with the outcome variable (Burgess & Thompson, 2011). However, most variables do not have sufficiently distinct ACE influences (Polderman et al., 2015), and single genetic variants are prone to weak instrument bias (Burgess & Thompson, 2011) (Fig. 1).

In combining both models, the MRDoC model tests unidirectional causation, does not require differential variance components, assumes no E correlations between variables of interest and overcomes weak-instrument bias by specifying polygenic scores as an instrument (Minică et al., 2018). The MRDoC model adjusts for potential violation of the properties of a valid instrument by specifying a pleiotropic path between the polygenic score and the outcome variable (Fig. 2). Covariance paths between A and C components further adjust for residual confounding which further reduces bias in the estimated causal path coefficient.

Mendelian randomization-direction of causation (MRDoC) model. Note. The MRDoC model combines the twin Direction of Causation (DOC) model (in the red box) with Mendelian Randomization (MR, in the blue box) to determine causal effects. In MRDoC Model 1, Same-Sex Attraction (SSA) is specified as the predictor and Psychological Distress (PD—indicated by Depressive and Anxiety symptoms (Dep and Anx respectively)) as the outcome. Genetic Propensity for Same-Sex Attraction (GPSSA, indicated by polygenic scores for same-sex attraction—PSSsa) is specified as the outcome. b1 and b2 represent the instrumental and pleiotropic paths respectively and g1 represents the causal path. Af1–2, Cf1–2 and Ef1–2 = Additive genetic and shared and individual-specific environmental influences on SSA and PD respectively; af1–2, cf1–2 and ef1–2 = their path coefficients; As1–2, Cs1–2 and Es1–2 = Residual additive genetic and shared and individual-specific environmental influences on Depressive (Dep) and Anxiety symptoms (Anx) respectively; and as1–2, cs1–2 and es1–2 = their path coefficients. In MRDoC model 2, Genetic propensity for Psychological Distress (GPPD), PD and SSA were specified as the instrument, predictor and outcome respectively

To assess sex differences in the causal paths, we compared heterogeneity MRDoC models (for MRDoC models 1 and 2) in which all the parameters were allowed to differ by sex with corresponding ones in which the causal paths were constrained to be equal in males and females (homogeneity models). Model comparison was done using likelihood-ratio testing. Preliminarily, we tested for sex differences in the distributions of the variables (using linear regressions with each variable specified as a separate outcome, sex as the predictor while controlling for familial clustering using the cluster option in STATA; Krebs et al., 2020) and their phenotypic correlations.

To test moderation by early-life adversities and childhood gender nonconformity, we specified moderation coefficients on the causal paths in MRDoC models 1 and 2 (Figure S2, Supplementary material). To minimize the false positive moderation of causal effects, we also specified moderation coefficients for the instrumental and pleiotropic paths, the A and E variance component paths and the A covariance path (Purcell, 2002). Furthermore, as cross-paths for the cross-twin within-pair correlations for the moderators were not specified in the moderation models, we used the extended fixed regression approach which controls for the main effects of the co-twin’s moderator variable (early-life adversity or childhood gender nonconformity) on each twin’s variables of interest: same-sex attraction and psychological distress (Van der Sluis et al., 2012).

Exploratory analyses

We further tested whether the causal paths in MRDoC Models 1 and 2 were mediated by victimization (Supplementary Figure S1). These analyses tested whether the causal influences of same-sex attraction on psychological distress were partly explained by victimization (MRDoC Model 3) and whether the reciprocal causal path between psychological distress and same-sex attraction was partly explained by victimization (MRDoC Model 4). Similar to the unmediated MRDoC model (Minică et al., 2018), the covariances between E influences on same-sex attraction, victimization and psychological distress were fixed to 0.

Preregistration

This study was pre-registered at https://osf.io/dgcm6/ and we departed from the proposed analyses as follows: Risky sexual behavior (RSB) was excluded from analyses because there was insufficient power to determine the direction of causation using the MRDoC model (i.e., both bidirectional causal path coefficients were similar in magnitude to the phenotypic correlation coefficient), possibly because of its small correlation with sexual orientation. Furthermore, we tested mediation of the MRDoC models directly by specifying victimization as a mediator in the model rather than indirectly by residualizing same-sex attraction and psychological distress on victimization before modelling.

Results

Descriptive statistics

The mean age of the participants was 22.3 (± 0.92) years. About 81% of the participants reported being always attracted to the opposite sex while the remainder reported varying degrees of same-sex attraction which ranged from 1.9% being mostly same-sex attracted and 11.5% being mostly attracted to the opposite sex (Table 1). More females (21.4%) reported being same-sex attracted compared to male participants (15.3%; F[1] = 29.43; p < 0.001). The median scores for depressive and anxiety symptoms, victimisation and early-life adversity were 3.0, 5.0, 2.0 and 4.0 respectively (Inter-quartile ranges: 6.0, 8.0, 5.0 and 5.0 respectively). The depressive and anxiety symptoms scores were higher in female participants (p < 0.001 in both instances) while the median victimisation score was significantly higher in male participants (p < 0.001 respectively). However, early-life adversity and childhood gender nonconformity did not significantly differ by sex.

Phenotypic factor correlations

There was a significant positive correlation between same-sex attraction and psychological distress (r = 0.30; 95% CI: 0.27, 0.33) such that increasing same-sex attraction was associated with higher psychological distress (Table 2). Genetic propensity for same-sex attraction (GPSSA) was significantly associated with same-sex attraction (r = 0.08; 95% CIs = 0.04, 0.12) but not psychological distress (r = 0.01; 95% CIs = −0.02, 0.05). Genetic propensity for psychological distress (GPPD) was also associated with psychological distress (r = 0.17, 95% CI: 0.13, 0.21) and same-sex attraction (r = 0.08, 95% CI: 0.03, 0.13). The significant association between GPPD and same-sex attraction (SSA) was consistent with pleiotropy of GPPD. Victimisation was also significantly correlated with same-sex attraction and psychological distress (r = 0.16 and 0.41; 95% CIs = 0.13, 0.19; and 0.39, 0.43 respectively). These phenotypic factor correlations were consistent with the variable correlations and are summarized in Table S2 in the Supplementary Material.

The cross-twin correlations for each factor among monozygotic twins were more than twice those in dizygotic twins indicating genetic rather than shared environmental influences on the factor variances (Table 2).

Biometric genetic models

Preliminary cholesky decomposition

The heritability estimates for same-sex attraction, psychological distress and victimization in the full ACE model were 54%, 54% and 32% (95% CIs: 0.40, 0.60; 0.43, 0.60 and 0.23, 0.36 respectively [Supplementary Table S3]). The standardized E contributions to the variances of the three factors were 46%, 46% and 68% (95% CIs: 0.40, 0.53; 0.40, 0.51 and 0.64, 0.72 respectively). As C influences on all three factors were each 0% and did not lead to a significant worsening of fit when dropped from the model (χ2[7] = 0.00, p = 1), this component was dropped from subsequent analyses and we report estimates from the AE model (Table 3).

Causal associations between same-sex attraction and psychological distress

The phenotypic correlation between same-sex attraction and psychological distress was resolved into bidirectional causal effects in two separate models. MRDoC Model 1 (Fig. 3a) depicts causal influences of same-sex attraction on psychological distress (standardized path coefficient = 0.19, 95% CIs: 0.09, 0.29) while MRDoC Model 2 (Fig. 3b) depicts reverse causality between psychological distress and same-sex attraction (standardized path coefficient = 0.17, 95% CIs: 0.08, 0.25). Pleiotropic effects of same-sex attraction and psychological distress instruments (GPSSA and GPPD respectively) on psychological distress and same-sex attraction respectively in both models were not statistically significant. Considering that the coefficient of the pleiotropic effect of GPSSA on psychological distress was 0 (Fig. 3a), we tested the impact of rE (correlation between individual-specific environmental influences) on the causal path coefficient. For this, we constrained the pleiotropic path coefficient to 0 and freely estimated rE. The causal and correlation path coefficients in this exploratory model (β = 0.18 and rA = 0.24 respectively; 95% CIs: 0.16, 0.22 and −0.29, 0.61; and rE = 0) were comparable to those of the main model. These suggest that the causal path estimate was not confounded by unmeasured rE and that statistical power to estimate rA is reduced when rE is estimated.

Mendelian Randomization-Direction of causation (MRDoC) models testing causal associations between same-sex attraction and psychological distress without and with victimization as a mediator including standardized path coefficients and 95% confidence intervals. Note. a MRDoC model 1: Causal influences of Same-Sex Attraction (SSA) on Psychological Distress (PD) with Genetic Propensity for Same-Sex Attraction (GPSSA) as instrument; b MRDoC model 2: Causal influences from PD towards SSA with Genetic Propensity for Psychological Distress (GPPD) as instrument; c MRDoC model 3: MRDoC Model 3: Model 1 with Victimization (VICT) included as a mediator; d MRDoC Model 4: Model 2 with Victimization included as a mediator. PSSsa, PSDep, PSAnx, Ssa, Dep and Anx = observed variables and indicators for the latent factors: Polygenic Scores for same-sex attraction, and for depressive and anxiety symptoms; Same-sex attraction, and Depressive and Anxiety symptoms respectively; af1–2, ef1–2 = additive genetic and individual-specific environmental influences on SSA and PD; a3–4 and e3–4 = residual additive genetic and individual-specific environmental influences on Depressive and Anxiety symptoms. The following constraints were specified for identification: factor loadings for single indicator factors (GPSSA and SSA) were fixed to 1 and the corresponding residual variances were fixed to 0; for PD, the unstandardized factor loading on Dep was fixed to 1 while a3 and a4 and e3 and e4 were constrained to be equal respectively. Solid lines indicate significant paths while broken lines indicate non-significant paths

Sex differences

The heterogeneity phenotypic factor correlation model fit the data better than the corresponding homogeneity model (χ2[52] = 877.60, p < 0.001). However, inspection of the correlation coefficients indicated that this difference likely reflected multiple small differences as all the confidence intervals of the parameter estimates overlapped. The homogeneity MRDoC models for MRDoC Models 1 and 2 (causal paths constrained to be equal in both sexes) were not significantly worse than the corresponding heterogeneity models (χ2[1] = 1.79, p = 0.18 and χ2[1] = 1.70, p = 0.19 respectively). This indicates that there were no significant sex differences in the causal effects. However, the large causal path estimates in males raises the possibility that the smaller absolute number of male participants may have reduced the power to estimate causal effects among them. Hence, we interpret this finding with caution.

Moderation by early-life adversity and childhood gender nonconformity

Although the causal effects of same-sex attraction on psychological distress increased with early-life adversity and childhood gender nonconformity (β = 0.02 and 0.03, 95% CIs: −0.02, 0.06 and −0.06, 0.11 respectively; Supplementary Table S3), these effects were not statistically significant. In contrast, the reverse causal path was significantly moderated by childhood gender nonconformity (β = −0.09, 95% CIs: −0.13, −0.04) but not early-life adversity (β = 0.05, 95% CIs: −0.01, 0.12). Specifically, reverse casual influences between psychological distress and same-sex attraction diminished as childhood gender nonconformity increased.

Exploratory analyses

Mediation of causal paths by victimization

Regarding the mediated causal effect of same-sex attraction on psychological distress (MRDoC Model 3, Fig. 3c), the standardized coefficient of the first mediation path (Same-sex attraction → Victimization) was 0.09 but this was not statistically significant (95% CI: 0.00, 0.18) while the second mediation path (Victimization → Psychological distress) was significant (standardized path coefficient = 0.26, 95% CIs: 0.22, 0.31). We note the similar magnitude of the coefficients of the first mediation path and the instrumental path (0.08, 95% CIs: 0.04, 0.12) in this model. The statistical significance of the latter, in contrast to the former, suggests that the present study is underpowered to detect a true mediated causal effect. This may, in turn, be a consequence of specifying same-sex attraction as a liability threshold variable (Neale et al., 1994). We therefore focus on the magnitude of effect rather than statistical significance. The proportion of causal effect mediated in this model was 12.5%

In contrast, in the mediation model for the reverse causal path (MRDoC Model 4, Fig. 3d) the first mediation path (Psychological distress → Victimization) was statistically significant (standardized path coefficient = 0.36, 95% CIs: 0.30, 0.42) while the magnitude of the second mediation path (Victimization → Same-sex attraction) was very close to 0 (standardized path coefficient = 0.01, 95% CIs: −0.05, 0.08). The indirect effect was thus 0%, while the direct effect remained statistically significant.

Discussion

The present study demonstrated bidirectional causal relationships between same-sex attraction (indexing sexuality-related stress) and psychological distress, consistent with the finding from a previous study (Oginni et al., 2022a). These effects did not appear to vary significantly by sex. Reciprocal causation between psychological distress and same-sex attraction was weaker at higher levels of childhood gender nonconformity. Finally, our findings suggest that victimization may partially mediate the causal effect of same-sex attraction on psychological distress but not the reverse causal path.

The causal influence of same-sex attraction on psychological distress demonstrated in the present study is consistent with prior evidence indicating that the phenotypic associations between same-sex attraction and adverse health outcomes are not confounded by correlated genetic and environmental influences (Oginni et al., 2020; Oginni et al., 2022c cf. Bailey, 2020). This contrasts with previous evidence of genetic and environmental correlations between same-sex attraction and depression (Frisell et al., 2010; Ganna et al., 2019; Zietsch et al., 2012). Specifically, our analyses demonstrated very small independent associations between same-sex attraction polygenic scores and psychological distress, and vice versa. Thus, the previously described genetic correlations may reflect vertical pleiotropy (i.e., genetic influences transmitted through phenotypic causal paths) rather horizontal pleiotropy (a common set of genetic factors independently influencing multiple outcomes; Oginni, et al., 2020, 2022c; Paaby & Rockman, 2013). The causal effect of same-sex attraction on psychological distress is also consistent with the minority stress theory in which stress associated with sexual minority status causes higher mental health adversities through intermediary affective, cognitive and behavioral processes (Feinstein, 2020; Hatzenbuehler, 2009; Meyer, 2003). This explanation is further validated by our finding that victimization explained 12.5% of the causal effect of same-sex attraction on psychological distress. The lack of statistical significance for this mediation effect is likely due to low power from specifying same-sex attraction as a liability threshold variable (Neale et al., 1994) and we interpret this effect with caution. The large direct (unmediated) effect suggests the role of other mediators (such as other minority stress factors) or confounders in this causal path.

The reverse causal effect of psychological distress on same-sex attraction (indexing sexuality-related stress) is consistent with a previous finding (Oginni et al., 2022a). However, although victimization was significantly causally influenced by psychological distress which was consistent with existing literature (Hart et al., 2012; Maniglio, 2009); it did not mediate this reverse causal path. Taken together, the separate significant causal associations between psychological distress and victimization are consistent with a feedback loop whereby sexuality-related victimization results in psychological distress which in turn increases the likelihood of further victimization. The large unmediated reverse causal effect (psychological distress → same-sex attraction) suggests that the mechanisms whereby psychological distress reinforces sexuality-related stress are independent of victimization. Alternatively, this unmediated effect may reflect phenotypic confounding by a variable that is associated with psychological distress, victimization and same-sex attraction. One such variable is childhood gender nonconformity which is associated with later same-sex attraction (Li et al., 2017; Xu et al., 2021), victimization and psychological distress (D’Augelli et al., 2006; Jones et al., 2017). However, when we controlled for childhood gender nonconformity as a covariate in mediation analyses, the causal and mediation path coefficients were largely unchanged. Another alternative possibility is that the unmediated reverse causal path reflects other minority stressors that are more proximal to same-sex attraction such as internalized and perceived stigma (Meyer, 2003) but this needs to be specifically tested.

Sex differences

Similarly, although previous studies suggested sex differences in the mental health disparities among sexual minority compared to heterosexual individuals (King et al., 2008); the present study found that the unmediated bidirectional causal paths were comparable in men and women. Our finding may suggest that the causal mechanisms of disparities in psychological distress among sexual minorities do not differ by sex. The sex differences found in earlier observational studies may reflect differences in the experience of minority stressors in sexual minority men compared to women. For example, in the present study, the median victimization score was higher among male compared to female participants. However, considering the large confidence intervals for the causal path coefficient among men, we recognize the possibility that our sample was too small to detect significant sex differences.

Moderation by early-life adversities and childhood gender nonconformity

We further demonstrated that the reciprocal causal path from psychological distress towards same-sex attraction weakened as childhood gender nonconformity increased. This suggests a protective effect whereby the feedback link of psychological distress on putative minority stress processes is attenuated among those with higher childhood gender nonconformity. For example, a recent meta-analysis found that gender nonconformity is significantly associated with lower internalized homonegativity (Thoma et al., 2021). Similarly, another recent study found that retrospectively-assessed childhood gender nonconformity attenuated individual-specific influences on the association between non-heterosexuality and anxiety symptoms (Oginni et al., 2022b). Although the causal effects of same-sex attraction on psychological distress appeared stronger with higher early-life adversities and childhood gender nonconformity, these effects were not statistically significant.

Strengths and limitations

The combination of genomic data with cross-sectional twin data enabled us to test bidirectional causal associations. The assessment of victimization in both same-sex attracted and heterosexual participants enabled the estimation of how much it contributed to cross-group differences in adverse health outcomes. The use of prospectively-assessed childhood gender nonconformity also helped minimize any effects of recall bias in this trait. However, despite these strengths, our findings need to be interpreted in the light of the following limitations.

The specification of same-sex attraction as a liability threshold variable is consistent with common practice for categorical variables (Neale et al., 1994). However, this specification reduced our power to investigate mediation of the causal effects and sex differences in these. We also tested for bidirectional causal effects in separate models as has been previously done (Oginni et al., 2022a) but these would have been better tested simultaneously in a single model. However, such a model would require assumptions such as the absence of pleiotropy that may bias causal path estimates (Castro-de-Araujo et al., 2022). Bidirectional causal effects may be tested simultaneously using other designs such as the direction of causation twin model (under certain conditions, Heath et al., 1993) and the longitudinal cross-lagged model (Burt et al., 2005).

Even though moderation of the causal paths by early-life adversity was not statistically significant, we note that intrapersonal factors such as significant psychological distress and personality traits like neuroticism may introduce recall bias, i.e., increase the likelihood of reporting or interpreting past events as traumatic (Larsen, 1992). Hence, caution should be taken in future studies replicating our analyses using larger sample sizes. Such studies may specify multiple measures of recalled adversity as indicators of a latent adversity measure (Heath et al., 1993; Schoemann & Jorgensen, 2021) or estimate individual-specific environmental correlation alongside the causal path coefficient if the model will be identified.

Although victimization and other stressful experiences are typically higher among sexual minorities, and are attributable to their sexual minority status or related traits like childhood gender nonconformity (King et al., 2003; Roberts et al., 2013), victimization in the present study was not specifically associated with sexual minority status. Thus, victimization in the present study may reflect other factors than same-sex attraction. Similarly, while we use same-sex attraction as an index of sexuality-related distress, future studies should incorporate specific indices in their analytic models.

Future directions

Future research can improve on the present study by incorporating other minority stressors such as internalized sexuality-related stigma (Meyer, 2003), and related mechanisms such as rumination (Timmins et al., 2020) and rejection sensitivity (Feinstein, 2020) as mediators of the demonstrated causal effects. These can potentially explain some of the unmediated direct effects in both causal paths. However, larger samples would be required for such analyses, and the investigation of sex differences in these mediation effects. Power may also be increased by assessing same-sex sexuality as a continuous measure.

As recommended in the description of the MRDoC model (Minică et al., 2018), we suggest the use of alternative research designs to provide external validation for the causal effects demonstrated in the present study (e.g., de Vries et al., 2021). Such designs may include biometric or phenotypic longitudinal cross-lagged models (Burt et al., 2005; Hamaker et al., 2015) which can simultaneously test bidirectional causal effects and be extended to test for causal mediation (Kline, 2015).

Conclusions

We demonstrated bidirectional causal effects between same-sex attraction (indexing sexuality-related stress) and psychological distress with no significant sex differences in these effects. Moderation analyses suggested a protective effect of childhood gender nonconformity on the effect of psychological distress on minority stress. Further mediation analyses suggested a feedback loop whereby minority stress increases the likelihood of psychological distress among sexual minorities which in turn reinforces minority stress.

The causal effect of same-sex attraction on psychological distress and mediation by victimization in the present study highlight the importance of systemic interventions targeted at reducing sexuality-based discrimination to improve the overall wellbeing of sexual minority individuals. The feedback loop between psychological distress and victimization in the context of sexual minority status further suggests the importance of addressing sexual minority stress during individual interventions for psychological distress among sexual minorities. The protective mechanisms of childhood gender nonconformity in this feedback process need to be specifically investigated.

Data availability

The data are available on request from the TEDS team at: https://www.teds.ac.uk/researchers/teds-data-access-policy.

Code availability

The code for analysis is freely available at: https://github.com/Kaoginni/MRDoC-mediation-and-moderation/blob/main/MRDoC%20-%20mediation,%20moderation,%20sex%20differences.R

Notes

Although these polygenic scores were based on a genome-wide association study for same-sex behavior, we describe them as ‘polygenic scores for same-sex attraction’ for ease of presentation.

References

Angold A, Costello EJ, Messer SC, Pickles A (1995) Development of a short questionnaire for use in epidemiological studies of depression in children and adolescents. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 5(4):237–249

Allison PD (2003) Missing data techniques for structural equation modeling. J Abnorm Psychol 112(4):545–557. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.545

Bailey JM, Vasey PL, Diamond LM, Breedlove SM, Vilain E, Epprecht M (2016) Sexual orientation, controversy, and science. Psychol Sci Public Interest 17(2):45–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100616637616

Bailey MJ (2020) The minority stress model deserves reconsideration, not just extension. Arch Sex Behav 49(7):2265–2268. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-019-01606-9

Bränström R (2017) Minority stress factors as mediators of sexual orientation disparities in mental health treatment: a longitudinal population-based study. J Epidemiol Community Health 71(5):446–452. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2016-207943

Burgess S, Thompson SG (2011) Bias in causal estimates from Mendelian randomization studies with weak instruments. Stat Med 30(11):1312–1323. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.4197

Burt SA, McGue M, Krueger RF, Iacono WG (2005) How are parent–child conflict and childhood externalizing symptoms related over time? Results from a genetically informative cross-lagged study. Dev Psychopathol 17(1):145–165. https://doi.org/10.1017/S095457940505008X

Castro-de-Araujo LFS, Singh M, Zhou YD, Vinh P, Verhulst B, Dolan CV, Neale MC (2022) MR-DoC2: bidirectional causal modeling with instrumental variables and data from relatives. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.14.484271

Craske M, Wittchen U, Bogels S, Stein M, Andrews G, Lebeu R (2013) Severity measure for generalized anxiety disorder-adult. American Psychiatric Association, Arlington

D’Augelli AR, Grossman AH, Starks MT (2006) Childhood gender atypicality, victimization, and PTSD among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. J Interpers Violence 21(11):1462–1482. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260506293482

de Vries LP, Baselmans BM, Luykx JJ, de Zeeuw EL, Minică CC, de Geus EJ, Vinkers CH (2021) Bartels M (2021) Genetic evidence for a large overlap and potential bidirectional causal effects between resilience and well-being. Neurobiol Stress 14:100315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ynstr.2021.100315

Dürrbaum T, Sattler FA (2020) Minority stress and mental health in lesbian, gay male, and bisexual youths: a meta-analysis. J LGBT Youth 17(3):298–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361653.2019.1586615

Feinstein BA (2020) The rejection sensitivity model as a framework for understanding sexual minority mental health. Arch Sex Behav 49(7):2247–2258. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-019-1428-3

Frisell T, Lichtenstein P, Rahman Q, Långström N (2010) Psychiatric morbidity associated with same-sex sexual behaviour: influence of minority stress and familial factors. Psychol Med 40(2):315–324. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291709005996

Ganna A, Verweij KJ, Nivard MG, Maier R, Wedow R, Busch AS et al (2019) Large-scale GWAS reveals insights into the genetic architecture of same-sex sexual behavior. Science 365(6456):eaat7693. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aat7693

Golombok S, Rust J (1993) The pre-school activities inventory: a standardized assessment of gender role in children. Psychol Assess 5(2):131–136. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.5.2.131

Guo Y, Kopec JA, Cibere J, Li LC, Goldsmith CH (2016) Population survey features and response rates: a randomized experiment. Am J Public Health 106(8):1422–1426. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303198

Hamaker EL, Kuiper RM, Grasman RP (2015) A critique of the cross-lagged panel model. Psychol Methods 20(1):102–116. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038889

Hart C, De Vet R, Moran P, Hatch SL, Dean K (2012) A UK population-based study of the relationship between mental disorder and victimisation. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 47(10):1581–1590. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-011-0464-7

Hatzenbuehler ML (2009) How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin”? A psychological mediation framework. Psychol Bull 135(5):707–730. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016441

Haworth CM, Davis OS, Plomin R (2013) Twins early development study (TEDS): a genetically sensitive investigation of cognitive and behavioral development from childhood to young adulthood. Twin Res Hum Genet 16(1):117–125. https://doi.org/10.1017/thg.2012.91

Heath AC, Kessler RC, Neale MC, Hewitt JK, Eaves LJ, Kendler KS (1993) Testing hypotheses about direction of causation using cross-sectional family data. Behav Genet 23(1):29–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01067552

Howard DM, Adams MJ, Clarke TK, Hafferty JD, Gibson J, Shirali M et al (2019) Genome-wide meta-analysis of depression identifies 102 independent variants and highlights the importance of the prefrontal brain regions. Nat Neurosci 22(3):343–352. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-018-0326-7

Jones A, Robinson E, Oginni O, Rahman Q, Rimes KA (2017) Anxiety disorders, gender nonconformity, bullying and self-esteem in sexual minority adolescents: Prospective birth cohort study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 58(11):1201–1209. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12757

King M, McKeown E, Warner J, Ramsay A, Johnson K, Cort C et al (2003) Mental health and quality of life of gay men and lesbians in England and Wales: controlled, cross-sectional study. Br J Psychiatry 183(6):552–558. https://doi.org/10.1192/03-207

King M, Semlyen J, Tai SS, Killaspy H, Osborn D, Popelyuk D, Nazareth I (2008) A systematic review of mental disorder, suicide, and deliberate self harm in lesbian, gay and bisexual people. BMC Psychiatry 8(1):1–17. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-8-70

Kline RB (2015) Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford publications, New York

Krebs G, Hannigan LJ, Gregory AM, Rijsdijk FV, Eley TC (2020) Reciprocal links between anxiety sensitivity and obsessive–compulsive symptoms in youth: a longitudinal twin study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 61(9):979–987. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13183

Larsen RJ (1992) Neuroticism and selective encoding and recall of symptoms: evidence from a combined concurrent-retrospective study. J Personality Soc Psychol 62(3):480–488. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.62.3.480

Li G, Kung KT, Hines M (2017) Childhood gender-typed behavior and adolescent sexual orientation: a longitudinal population-based study. Dev Psychol 53(4):764–777. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000281

Maniglio R (2009) Severe mental illness and criminal victimization: a systematic review. Acta Psychiatr Scand 119(3):180–191. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01300.x

McGue M, Bouchard TJ (1984) Adjustment of twin data for the effects of age and sex. Behav Genet 14(4):325–343. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01080045

Meyer IH (2003) Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull 129(5):674–697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

Meyer IH (2010) The right comparisons in testing the minority stress hypothesis: comment on Savin-Williams, Cohen, Joyner, and Rieger (2010). Arch Sex Behav 39(6):1217–1219. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-010-9670-8

Minică CC, Boomsma DI, Dolan CV, de Geus E, Neale MC (2020) Empirical comparisons of multiple Mendelian randomization approaches in the presence of assortative mating. Int J Epidemiol 49(4):1185–1193. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyaa013

Minică CC, Dolan CV, Boomsma DI, de Geus E, Neale MC (2018) Extending causality tests with genetic instruments: an integration of Mendelian randomization with the classical twin design. Behav Genet 48(4):337–349. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10519-018-9904-4

Mynard H, Joseph S (2000) Development of the multidimensional peer-victimization scale. Aggress Behav 26(2):169–178. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-2337(2000)26:2%3c169::AID-AB3%3e3.0.CO;2-A

Neale MC, Cardon LR (2013) Methodology for genetic studies of twins and families, vol 67. Springer Science & Business Media, Dordrecht

Neale MC, Eaves LJ, Kendler KS (1994) The power of the classical twin study to resolve variation in threshold traits. Behav Genet 24(3):239–258. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01067191

Neale MC, Hunter MD, Pritikin JN, Zahery M, Brick TR, Kirkpatrick RM et al (2016) OpenMx 2.0: extended structural equation and statistical modeling. Psychometrika 81(2):535–549. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11336-014-9435-8

Oginni OA, Alanko K, Jern P, Rijsdijk FV (2022b) Increased depressive and anxiety symptoms in non-heterosexual individuals: moderation by childhood factors using a twin design. J Affect Disord 297:508–516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.10.095

Oginni OA, Jern P, Rahman Q, Rijsdijk FV (2022c) Do psychosocial factors mediate sexual minorities’ risky sexual behaviour? A twin study. Health Psychol 41(1):76–84. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0001129

Oginni OA, Jern P, Rijsdijk FV (2020) Mental health disparities mediating increased risky sexual behavior in sexual minorities: a twin approach. Arch Sex Behav 49(7):2497–2510. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-020-01696-w

Oginni OA, Lim KX, Purves KL, Lu Y, Johansson A, Jern P, Rijsdijk FV (2022a) Causal influences of same-sex attraction on psychological distress and risky sexual behaviors: evidence for bidirectional effects. Arch Sex Behav. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-022-02455-9

Oginni OA, Robinson EJ, Jones A, Rahman Q, Rimes KA (2019) Mediators of increased self-harm and suicidal ideation in sexual minority youth: a longitudinal study. Psychol Med 49(15):2524–2532. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329171800346X

Paaby AB, Rockman MV (2013) The many faces of pleiotropy. Trends Genet 29(2):66–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tig.2012.10.010

Plöderl M, Tremblay P (2015) Mental health of sexual minorities: a systematic review. Int Rev Psychiatry 27(5):367–385. https://doi.org/10.3109/09540261.2015.1083949

Polderman TJ, Benyamin B, De Leeuw CA, Sullivan PF, Van Bochoven A, Visscher PM, Posthuma D (2015) Meta-analysis of the heritability of human traits based on fifty years of twin studies. Nat Genet 47(7):702–709. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3285

Price TS, Freeman B, Craig I, Petrill SA, Ebersole L, Plomin R (2000) Infant zygosity can be assigned by parental report questionnaire data. Twin Res Hum Genet 3(3):129–133. https://doi.org/10.1375/twin.3.3.129

Purcell S (2002) Variance components models for gene–environment interaction in twin analysis. Twin Res Hum Genet 5(6):554–571. https://doi.org/10.1375/twin.5.6.554

Purves KL, Coleman JR, Meier SM, Rayner C, Davis KA, Cheesman R et al (2020) A major role for common genetic variation in anxiety disorders. Mol Psychiatry 25(12):3292–3303. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-019-0559-1

Rijsdijk FV, Sham PC (2002) Analytic approaches to twin data using structural equation models. Brief Bioinform 3(2):119–133. https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/3.2.119

Rimfeld K, Malanchini M, Spargo T, Spickernell G, Selzam S, McMillan A et al (2019) Twins early development study: a genetically sensitive investigation into behavioral and cognitive development from infancy to emerging adulthood. Twin Res Hum Genet 22(6):508–513. https://doi.org/10.1017/thg.2019.56

Roberts AL, Rosario M, Slopen N, Calzo JP, Austin SB (2013) Childhood gender nonconformity, bullying victimization, and depressive symptoms across adolescence and early adulthood: an 11-year longitudinal study. J Am Academy Child Adolesc Psychiatry 52(2):143–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2012.11.006

Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J, Gwadz M (2002) Gay-related stress and emotional distress among gay, lesbian and bisexual youths: a longitudinal examination. J Consult Clin Psychol 70(4):967. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.70.4.967

Schoemann AM, Jorgensen TD (2021) Testing and interpreting latent variable interactions using the semTools package. Psych 3(3):322–335. https://doi.org/10.3390/psych3030024

Schwartz S, Meyer IH (2010) Mental health disparities research: the impact of within and between group analyses on tests of social stress hypotheses. Soc Sc Med 70(8):1111–1118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.11.032

Semlyen J, King M, Varney J, Hagger-Johnson G (2016) Sexual orientation and symptoms of common mental disorder or low wellbeing: combined meta-analysis of 12 UK population health surveys. BMC Psychiatry 16(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-016-0767-z

Thoma BC, Eckstrand KL, Montano GT, Rezeppa TL, Marshal MP (2021) Gender nonconformity and minority stress among lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals: a meta-analytic review. Perspect Psychol Sci 16(6):1165–1183. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691620968766

Timmins L, Rimes KA, Rahman Q (2020) Minority stressors, rumination, and psychological distress in lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. Arch Sex Behav 49(2):661–680. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-019-01502-2

Van der Sluis S, Posthuma D, Dolan CV (2012) A note on false positives and power in G×E modelling of twin data. Behav Genet 42(1):170–186. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10519-011-9480-3

Vilhjálmsson BJ, Yang J, Finucane HK, Gusev A, Lindström S, Ripke S et al (2015) Modeling linkage disequilibrium increases accuracy of polygenic risk scores. Am J Hum Genet 97(4):576–592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.09.001

Xu Y, Norton S, Rahman Q (2021) Childhood gender nonconformity and the stability of self-reported sexual orientation from adolescence to young adulthood in a birth cohort. Dev Psychol 57(4):557–569. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0001164

Zietsch BP, Verweij KJ, Heath AC, Madden PA, Martin NG, Nelson EC, Lynskey MT (2012) Do shared etiological factors contribute to the relationship between sexual orientation and depression? Psychol Med 42(3):521–532. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291711001577

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the ongoing contribution of the participants in the Twins Early Development Study (TEDS) and their families. TEDS is supported by a programme grant from the UK Medical Research Council to Thalia Eley (MR/V012878/1) and previously to Robert Plomin (MR/M021475/1).

Funding

The present study did not receive any specific funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

OAO and FVR conceptualized the study, OAO carried out the analyses, OAO and FVR prepared the first draft of the manuscript, all the authors read the manuscript drafts and approved the final draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Olakunle A. Oginni, Kai X. Lim, Qazi Rahman, Patrick Jern, Thalia C. Eley, and Frühling V. Rijsdijk have no conflict of interest to declare.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was granted by King’s College London’s ethics committee for the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, protocol number is PNM/09/10-104.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Human and Animal Rights

This article does not contain any studies with animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Handling Editor: Yoon-Mi Hur.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Oginni, O.A., Lim, K.X., Rahman, Q. et al. Bidirectional Causal Associations Between Same-Sex Attraction and Psychological Distress: Testing Moderation and Mediation Effects. Behav Genet 53, 118–131 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10519-022-10130-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10519-022-10130-x