Abstract

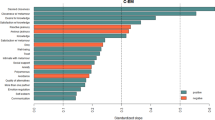

Despite considerable progress, research on sexual minorities has been hindered by a lack of clarity and consistency in defining sexual minority groups. Further, despite recent recommendations to assess the three main dimensions of sexual orientation—identity, behavior, and attraction—it remains unclear how best to integrate such multivariate information to define discrete sexual orientation groups, particularly when identity and behavior fail to match. The current study used a data-driven approach to identify a parsimonious set of sexual orientation classes. Latent profile analysis (LPA) was run within a large (N = 3182) and sexually diverse sample, using dimensions of sexual identity, behavior, and attraction as predictors. LPAs supported four fundamental sexual orientation classes not only in the overall sample, but also when conducted separately in men (n = 980) and women (n = 2175): heterosexual, homosexual, bisexual, and heteroflexible (a class representing individuals who self-identify as heterosexual or mostly heterosexual but report moderate same-sex sexual behavior and attraction). Heterosexuals reported the highest levels of psychological functioning and lowest risk behaviors. Homosexuals showed similarly high levels of psychological functioning to heterosexuals, but higher levels of risk behaviors. Bisexuals and heteroflexibles showed similarly low levels of psychological functioning and high risk taking. To facilitate applications of this classification approach, the study developed the Multivariate Sexual Orientation Classification System, reproducing the four LPA groups with 97% accuracy (kappa = .95) using just two items. Implications of this classification approach are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Given its clarity of meaning and widespread use throughout the literature, we have chosen to use the term “opposite sex” when we are referring to individuals with a different gender identity. Per a reviewer’s thoughtful suggestion, we considered using the term “different sex” to be more inclusive of non-binary gender identities. Unfortunately, we found that term to be confusing in a number of places (e.g., when referring to “different sex partners” in the last year), and so we decided to continue using the most common term for this construct.

A common concern with survey research is inattentive responding. Thankfully, rates of excessively inattentive responding for online surveys (similar in content, format, and length to the current study) tend to be fairly low (roughly 3–5%; see Maniaci & Rogge, 2014a). Despite such low rates, removing inattentive participants can lead to slight increases in power for correlational analyses (Maniaci & Rogge, 2014a). Identifying incomplete participants and participants completing the survey too rapidly are accepted methods of identifying such individuals (see Maniaci & Rogge, 2014b for a review as well as Maniaci & Rogge, 2014a for a review and supporting results). The cutscores used in the current article were developed by the second author across over 30 online surveys collecting data from over 40,000 participants. On average, participants answer an average of 11 questions per minute on surveys like the one presented in this manuscript. Thus, we used a cutscore of 26 questions per minute or more to identify participants rushing through the survey too quickly (at a pace more than double the average, strongly suggesting that they cannot be reading each item carefully). We also used a cutscore of completing at least 70% of the baseline survey as that helps to quickly separate out individuals who drop out of the survey after the first couple pages and to retain those with truly usable multivariate data.

The ANCOVAs controlled for the six demographic variables showing significant differences across the latent groups–thereby helping to defray the impact of those demographic differences when examining group means on the remaining variables.

Notably, this discussion is limited to a self-report survey method as it represents the most commonly used method of assessing sexual orientation; other methods (interview, psychophysiological, behavioral) are beyond the scope of this work.

References

Austin, S. B., Roberts, A. L., Corliss, H. L., & Molnar, B. E. (2008). Sexual violence victimization history and sexual risk indicators in a community-based urban cohort of “mostly heterosexual” and heterosexual young women. American Journal of Public Health, 98, 1015–1020. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2006.099473.

Austin, S. B., Ziyadeh, N., Fisher, L. B., Kahn, J. A., Colditz, G. A., & Frazier, A. L. (2004a). Sexual orientation and tobacco use in a cohort study of US adolescent girls and boys. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 158, 317–322. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.158.4.317.

Austin, S. B., Ziyadeh, N., Kahn, J. A., Camargo, C. A., Colditz, G. A., & Field, A. E. (2004b). Sexual orientation, weight concerns, and eating-disordered behaviors in adolescent girls and boys. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 43, 1115–1123. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.chi.0000131139.93862.10.

Badgett, M. V. L. (2009). Best practices for asking questions about sexual orientation on surveys. The Williams Institute, UCLA School of Law. Retrieved May 14, 2017, from http://escholarship.org/uc/item/706057d5.

Bailey, J. M., Vasey, P. L., Diamond, L. M., Breedlove, S. M., Vilain, E., & Epprecht, M. (2016). Sexual orientation, controversy, and science. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 17, 45–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100616637616.

Beaulieu-Prevost, D., & Fortin, M. (2015). The measurement of sexual orientation: Historical background and current practices. Sexologies, 24, e15–e19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sexol.2014.05.006.

Brewster, K. L., & Tillman, K. H. (2012). Sexual orientation and substance use among adolescents and young adults. American Journal of Public Health, 102, 1168–1176. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300261.

Bush, K., Kivlahan, D. R., McDonell, M. B., Fihn, S. D., & Bradley, K. A. (1998). The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C). Archives of Internal Medicine, 158, 1789–1795. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000374-199811000-00034.

Calzo, J. P. (2014). Applying a pattern-centered approach to understanding how attachment, gender beliefs, and homosociality shape college men’s sociosexuality. Journal of Sex Research, 51, 221–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2012.724119.

Calzo, J. P., Masyn, K. E., Austin, S. B., Jun, H. J., & Corliss, H. L. (2017). Developmental latent patterns of identification as mostly heterosexual versus lesbian, gay, or bisexual. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 27, 246–253. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12266.

Chung, Y. B., & Katayama, M. (1996). Assessment of sexual orientation in lesbian/gay/bisexual studies. Journal of Homosexuality, 30, 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v30n04_03.

Cochran, S. D., Mays, V. M., & Sullivan, J. G. (2003). Prevalence of mental disorders, psychological distress, and mental health services use among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71, 53–61. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.71.1.53.

Conron, K. J., Mimiaga, M. J., & Landers, S. J. (2010). A population-based study of sexual orientation identity and gender differences in adult health. American Journal of Public Health, 100, 1953–1960. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2009.174169.

Copen, C. E., Chandra, A., & Febo-Vazquez, I. (2016). Sexual behavior, sexual attraction, and sexual orientation among adults aged 18–44 in the United States: Data from the 2011–2013 National Survey of Family Growth. National Health Statistics Reports, 88, 1–14. Retrieved May 14, 2017, from http://europepmc.org/abstract/med/26766410.

Corliss, H. L., Austin, S. B., Roberts, A. L., & Molnar, B. E. (2009). Sexual risk in “mostly heterosexual” young women: Influence of social support and caregiver mental health. Journal of Women’s Health, 18, 2005–2010. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2009.1488.

Corliss, H. L., Rosario, M., Wypij, D., Fisher, L. B., & Austin, S. B. (2008). Sexual orientation disparities in longitudinal alcohol use patterns among adolescents: Findings from the Growing Up Today Study. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 162, 1071–1078. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.162.11.1071.

Diamond, L. M. (2008). Sexual fluidity: Understanding women’s love and desire. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Dodge, B., & Sandfort, T. (2007). A review of mental health research on bisexual individuals when compared to homosexual and heterosexual individuals. In B. A. Firestein (Ed.), Becoming visible: Counseling bisexuals across the lifespan (pp. 28–51). New York: Columbia University Press.

Everett, B. G. (2013). Sexual orientation disparities in sexually transmitted infections: Examining the intersection between sexual identity and sexual behavior. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 42, 225–236. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-012-9902-1.

Feinstein, B. A., & Dyar, C. (2017). Bisexuality, minority stress, and health. Current Sexual Health Reports, 9, 42–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11930-017-0096-3.

Fish, J. N., & Pasley, K. (2015). Sexual (minority) trajectories, mental health, and alcohol use: A longitudinal study of youth as they transition to adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44, 1508–1527. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-015-0280-6.

Flores, S. A., Mansergh, G., Marks, G., Guzman, R., & Colfax, G. (2009). Gay identity-related factors and sexual risk among men who have sex with men in San Francisco. AIDS Education and Prevention, 21, 91–103. https://doi.org/10.1521/aeap.2009.21.2.91.

Gagne, M., Ryan, R., & Bargmann, K. (2003). Autonomy support and need satisfaction in the motivation and well-being of gymnasts. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 15, 372–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200390238031.

Gates, G. J. (2011). How many people are lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender? The Williams Institute, UCLA School of Law. Retrieved May 14, 2017, from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/09h684x2.

Gates, G. J. (2012). LGBT identity: A demographer’s perspective. Loyola of Los Angeles Law Review, 45, 693–714. Retrieved May 14, 2017, from http://escholarship.org/uc/item/53x3r16j.

Grov, C., Hirshfield, S., Remien, R. H., Humberstone, M., & Chiasson, M. A. (2013). Exploring the venue’s role in risky sexual behavior among gay and bisexual men: An event-level analysis from a national online survey in the U.S. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 42, 291–302. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-011-9854-x.

Guadamuz, T. E., Lim, S. H., Marshal, M. P., Friedman, M. S., Stall, R. D., & Silvestre, A. J. (2012). Sexual, behavioral, and quality of life characteristics of healthy weight, overweight, and obese gay and bisexual men: Findings from a prospective cohort study. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 41, 385–389.

Institute of Medicine. (2011). The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: Building a foundation for better understanding. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/13128.

Kalichman, S. C., & Rompa, D. (1995). Sexual sensation seeking and sexual compulsivity scales: Validity, and predicting HIV risk behavior. Journal of Personality Assessment, 65, 586–601. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa6503_16.

Kinsey, A. C., Pomeroy, W. B., & Martin, C. E. (1948). Sexual behavior in the human male. Philadephia, PA: W.B. Saunders.

Klein, F., Sepekoff, B., & Wolf, T. J. (1985). Sexual orientation: A multi-variable dynamic process. Journal of Homosexuality, 11, 35–49. https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v11n01_04.

Legate, N., Ryan, R. M., & Rogge, R. D. (2017). Daily autonomy support and sexual identity disclosure predicts daily mental and physical health outcomes. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 43, 860–873. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167217700399.

Lindley, L. L., Walsemann, K. M., & Carter, J. W. (2012). The association of sexual orientation measures with young adult’s health-related outcomes. American Journal of Public Health, 102, 1177–1185. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300262.

Lippa, R. A. (2006). Is high sex drive associated with increased sexual attraction to both sexes? It depends on whether you are male or female. Psychological Science, 17, 46–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01663.x.

Lippa, R. A. (2007). The relation between sex drive and sexual attraction to men and women: A cross-national study of heterosexual, bisexual, and homosexual men and women. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 36, 209–222. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-006-9146-z.

Maniaci, M. R., & Rogge, R. D. (2014a). Caring about carelessness: Participant inattention and its effects on research. Journal of Research in Personality, 48, 61–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2013.09.008.

Maniaci, M., & Rogge, R. D. (2014b). Conducting research on the Internet. In H. T. Reis & C. M. Judd (Eds.), Handbook of research methods in social and personality psychology (2nd ed., pp. 443–470). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Martin-Storey, A., Cheadle, J. E., Skalamera, J., & Crosnoe, R. (2015). Exploring the social integration of sexual minority youth across high school contexts. Child Development, 86, 965–975. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12352.

Matthews, D. D., Blosnich, J. R., Farmer, G. W., & Adams, B. J. (2014). Operational definitions of sexual orientation and estimates of adolescent health risk behaviors. LGBT Health, 24, 42–49. https://doi.org/10.1097/OPX.0b013e3182540562.

McCutcheon, A. L. (1987). Latent class analysis. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 674–697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2012). MPlus (Version 7). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

Norris, A. L., Marcus, D. K., & Green, B. A. (2015). Homosexuality as a discrete class. Psychological Science, 26, 1843–1853. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797615598617.

Penke, L., & Asendorpf, J. B. (2008). Beyond global sociosexual orientations: A more differentiated look at sociosexuality and its effects on courtship and romantic relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95, 1113–1135. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.95.5.1113.

Przedworski, J. M., McAlpine, D. D., Karaca-Mandic, P., & VanKim, N. A. (2014). Health and health risks among sexual minority women: An examination of 3 subgroups. American Journal of Public Health, 104, 1045–1047. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301733.

Purcell, D. W., Johnson, C. H., Lansky, A., Prejean, J., Stein, R., Denning, P., … Crepaz, N. (2012). Estimating the population size of men who have sex with men in the United States to obtain HIV and syphilis rates. Open AIDS Journal, 6, 98–107. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874613601206010098.

Rosario, M., Corliss, H. L., Everett, B. G., Reisner, S. L., Austin, S. B., Buchting, F. O., & Birkett, M. (2014). Sexual orientation disparities in cancer-related risk behaviors of tobacco, alcohol, sexual behaviors, and diet and physical activity: Pooled youth risk behavior surveys. American Journal of Public Health, 104, 245–254. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301506.

Rosenberg, M. (1979). Conceiving the self. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Ross, L. E., Salway, T., Tarasoff, L. A., MacKay, J. M., Hawkins, B. W., & Fehr, C. P. (2018). Prevalence of depression and anxiety among bisexual people compared to gay, lesbian, and heterosexual individuals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Sex Research, 55, 435–456. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2017.1387755.

Rumpf, H.-J., Hapke, U., Meyer, C., & John, U. (2002). Screening for alcohol use disorders and at-risk drinking in the general population: Psychometric performance of three questionnaires. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 37, 261–268. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/37.3.261.

Savin-Williams, R. C. (2016). Sexual orientation: Categories or continuum? Commentary on Bailey et al. (2016). Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 17, 37–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100616637618.

Savin-Williams, R. C., Joyner, K., & Rieger, G. (2012). Prevalence and stability of self-reported sexual orientation identity during young adulthood. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 41, 103–110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-012-9913-y.

Savin-Williams, R. C., & Ream, G. L. (2007). Prevalence and stability of sexual orientation components during adolescence and young adulthood. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 36, 385–394. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-006-9088-5.

Savin-Williams, R. C., & Vrangalova, Z. (2013). Mostly heterosexual as a distinct sexual orientation group: A systematic review of the empirical evidence. Developmental Review, 33, 58–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2013.01.001.

Sell, R. L. (1997). Defining and measuring sexual orientation: A review. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 26, 643–658. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024528427013.

Sell, R. L. (2007). Defining and measuring sexual orientation for research. In I. H. Meyer & M. E. Northridge (Eds.), The health of sexual minorities: Public health perspectives on lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender populations (pp. 355–374). New York: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-31334-4_14.

Semlyen, J., King, M., Varney, J., & Hagger-Johnson, G. (2016). Sexual orientation and symptoms of common mental disorder or low well-being: Combined meta-analysis of 12 UK population health surveys. BMC Psychiatry, 16, 67. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-016-0767-z.

Spitzer, R. L. (2003). Can some gay men and lesbians change their sexual orientation? 200 participants reporting a change from homosexual to heterosexual orientation. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 32, 403–417. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025647527010.

Tangney, J. P., Baumeister, R. F., & Boone, A. L. (2004). High self-control predicts good adjustment, less pathology, better grades, and interpersonal success. Journal of Personality, 72, 271–324. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-3506.2004.00263.x.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2010). Healthy People 2020: Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender health. Retrieved May 14, 2017, from https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/lesbiangay-bisexual-and-transgender-health.

van Anders, S. M. (2015). Beyond sexual orientation: Integrating gender/sex and diverse sexualities via sexual configurations theory. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44, 1177–1213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-015-0490-8.

Vrangalova, Z., & Savin-Williams, R. C. (2012). Mostly heterosexual and mostly gay/lesbian: Evidence for new sexual orientation identities. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 41, 85–101.

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., Weber, K., Assenheimer, J. S., Strauss, M. E., & McCormick, R. A. (1995). Testing a tripartite model: II. Exploring the symptom structure of anxiety and depression in student, adult, and patient samples. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 104, 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.104.1.3.

Weibley, S., & Hindin, M. (2011). Self-identified lesbian internalized homophobia scale. In T. D. Fisher, C. M. Davis, W. L. Yarber, & S. L. Davis (Eds.), Handbook of sexuality-related measures (3rd ed., pp. 400–402). New York, NY: Routledge.

Wohl, A. R., Johnson, D. F., Lu, S., Jordan, W., Beall, G., Currier, J., & Simon, P. A. (2002). HIV risk behaviors among African American men in Los Angeles County who self-identify as heterosexual. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 31, 354–360. https://doi.org/10.1097/00126334-200211010-00013.

Wolff, M., Wells, B., Ventura-DiPersia, C., Renson, A., & Grov, C. (2016). Measuring sexual orientation: A review and critique of U.S. data collection efforts and implications for health policy. Journal of Sex Research, 54, 507–531. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2016.1255872.

Xu, F., Sternberg, M. R., & Markowitz, L. E. (2010a). Men who have sex with men in the United States: Demographic and behavioral characteristics and prevalence of HIV and HSV-2 infection: Results from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001-2006. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 37, 399–405. https://doi.org/10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181ce122b.

Xu, F., Sternberg, M. R., & Markowitz, L. E. (2010b). Women who have sex with women in the United States: Prevalence, sexual behavior and prevalence of herpes simplex virus type 2 infection—Results from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001–2006. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 37, 407–413. https://doi.org/10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181db2e18.

Zellner, J. A., Martínez-Donate, A. P., Sañudo, F., Fernández-Cerdeño, A., Sipan, C. L., Hovell, M. F., & Carrillo, H. (2009). The interaction of sexual identity with sexual behavior and its influence on HIV risk among Latino men: Results of a community survey in northern San Diego County, California. American Journal of Public Health, 99, 125–132. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2007.129809.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

See Table 5.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Legate, N., Rogge, R.D. Identifying Basic Classes of Sexual Orientation with Latent Profile Analysis: Developing the Multivariate Sexual Orientation Classification System. Arch Sex Behav 48, 1403–1422 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1336-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1336-y