Abstract

Some forms of argumentation are best performed through words. However, there are also some forms of argumentation that may be best presented visually. Thus, this paper examines the virtues of visual argumentation. What makes visual argumentation distinct from verbal argumentation? What aspects of visual argumentation may be considered especially beneficial?

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

As mentioned elsewhere (Sonesson 2010a, b), Eco’s view of iconicity differs and develops in his work from viewing it as being based on conventionality (e.g. 1972), to proportionality (1979, 1984), and finally viewing icons as mirrors affording a direct view onto reality (2000). It should be noted that my discussion here does not deal with iconicity in general, but with the rhetorical affordances of pictures. Eco (1979: p. 232 ff.) distinguishes between several different types of articulation (e.g. without; second only; first only; two and three articulations as well as mobile articulation); however, it is not altogether clear how he positions pictures such as photographs.

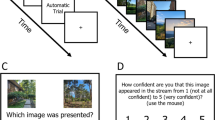

The three focus group interviews were carried out in Norway during June 2014. The groups consisted of six pensioners in their 70s, five young women aged 18–19, and four university students —all unknown to one another. The respondents were briefly informed about the proposed amendment and the organisation “every1against1” and then shown the ad without any mention of the possible message or content. Even though the respondents were Norwegian, and their verbal responses somewhat colloquial, they still clearly captured the general thrust of the argument as I have described it with claim, ground and warrant.

The point is neither to claim that this is “the correct interpretation” nor to claim that audiences will necessarily interpret the ad in this way—even though this is what the focus group interviews clearly suggest. The point is simply to show that the ad invites the construction of a specific argument, and that the respondents generally made the intended inference.

We may also say that they have more weight or strength.

Even though Christian Kock has used the term “weight” in some publications (e.g. 2007b), he expresses resistance to using this term in other publications, because it seems to indicate that everything can be measured on the same scale, thereby neglecting the intersubjectivity and multidimensionality of rhetorical reasoning (Kock 2003, 2007a, 2009). Kock now seems to prefer the term argument strength. Unfortunately, Toulmin (1958) equates strength with soundness, validity and cogency, which differs from Kock’s use of strength.

I am aware that many argumentation scholars are deeply sceptical of notions such as strength, weight, and importance in argumentation theory. Because of the element of subjectivity in this kind of argumentation appraisal, some theorists label this kind of thinking relativistic. However, as Kock has argued, there is necessarily “inherent audience-relativity of argumentation over issues where values are involved” (Kock 2007b, p. 189). Calling an argumentation theory that takes strength, importance and values into considerations relativistic” does not make the facts it describes less true or more avoidable” (Kock 2007a, p. 105).

E.g. Huffington Post 3/13/2013. See http://www.huffingtonpost.com/michael-moore/newtown-gun-control_b_2866126.html (downloaded July 14, 2014). Cf. Hollywood Reporter 06/02/2013. See http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/michael-moore-sandy-hook-no-562002 (downloaded July 14, 2014).

This, of course, is different from the question of guilt, where the emotional appeal of images is rightly banned, but where visual documentation may serve a purpose.

I thank the anonymous reviewer for pointing this out.

References

Barthes, R. 1977. Image, music, text. London: Fontana Press.

Birdsell, D., and L. Groarke. 1996. Towards a theory of visual argument. Argumentation and Advocacy 33: 1–10.

Birdsell, D., and L. Groarke. 2007. Outlines of a theory of visual argument. Argumentation and Advocacy 43: 103–113.

Blair, J.A. 1996. The possibility and actuality of visual argument. Argumentation and Advocacy 33: 1–10.

Blair, J.A. 2004. The rhetoric of visual arguments. In Defining visual rhetorics, ed. C.A. Hill, and M. Helmers, 137–151. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Blair, JA. 2012. Groundwork in the theory of argumentation. Amsterdam: Argumentation Library 21.

Chandler, D. 2006. Semiotics: The basics. New York: Routledge.

Damasio, A.R. 1994. Descartes’ error : Emotion, reason, and the human brain. New York: Putnam.

Domke, D., D. Perlmutter, and M. Spratt. 2002. The primes of our times? An examination of the ‘power’ of visual images. Journalism 3(2): 131–159.

Eco, U. 1972. Introduction to a semiotics of iconic signs. In VS 2: 1–14.

Eco, U. 1979. A theory of semiotics. Indiana: Indiana University Press.

Eco, U. 1984. Semiotics and the philosophy of language. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Eco, U. 2000. Kant and the platypus. New York: Harcourt Brance and Co.

Eemeren, F.H., R. van Grootendorst, F.S. Henkemans, J.A. Blair, R.H. Johnson, E.C.W. Krabbe, C. Plantin, D.N. Walton, C.A. Willard, J. Woods, and D. Zarefsky. 2009. Fundamentals of argumentation theory. New York/London: Routledge.

Geertz, C. 1973. Thick description: Toward an interpretive theory of culture. The interpretation of cultures: Selected essays, 3–30. New York: Basic Books.

Gombrich, E.H. 1982. The image and the eye: Further studies in the psychology of pictorial representation. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Groarke, L. 1996. Logic, art and argument. Informal logic 18: 105–129.

Groarke, L. 2009. Five theses on toulmin and visual argument. In Pondering on problems of argumentation: Twenty essays on theoretical issues, ed. F.H. van Eemeren, and B. Garssen, 229–239. Amsterdam: Springer.

Hariman, R., and J. Lucaites. 2007. No caption needed: Iconic photographs, public culture and liberal democracy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kjeldsen, JE. 2002 Visuel retorik [Visual Rhetoric]. Dr. art avhandling. IMV-utgivelse nr. 50. Bergen: Institutt for medievitenskap, UiB.

Kjeldsen, J.E. 2007. Visual argumentation in Scandinavian political advertising: A cognitive, contextual, and reception-oriented approach. Argumentation and Advocacy 43: 124–132.

Kjeldsen, J.E. 2012a. Pictorial argumentation in advertising: Visual tropes and figures as a way of creating visual argumentation. In Topical themes in argumentation theory: Twenty exploratory studies, ed. F.H. van Eemeren, and B. Garssen, 239–255. Dordrecht: Springer.

Kjeldsen, JE. 2012b. Four rhetorical qualities of pictures. Paper presented at the th Biennial RSA Conference. May 25–28, 2012. The Loews Philadelphia Hotel, Philadelphia, PA.

Kjeldsen, J.E. 2012c. At argumentere med billeder [Making arguments with pictures]. Rhetorica Scandinavica 60: 27–49.

Kock, C. 2013. Defining rhetorical argumentation. Philosophy and Rhetoric 46(4): 437–464.

Kock, C. 2003. Multidimensionality and non-deductiveness in deliberative argumentation. In anyone who has a view: Theoretical contributions to the study of argumentation, eds. Frans H. Van van Eemeren, F.H., Blair, JA, Willard, CA, Henkemans, AFS, 157–171. Argumentation Library Volume 8. Amsterdam: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Kock, C. 2007a. Is practical reasoning presumptive? Informal Logic 27(1): 91–108.

Kock, C. 2007b. Norms of legitimate dissensus. Informal Logic 27(2): 179–196.

Kock, C. 2009. Choice is not true or false: The domain of rhetorical argumentation. Argumentation 23: 61–80.

Kress, G., and T. van Leeuwen. 1996. Reading images. London and New York: Routledge.

Lake, R.A., and B.A. Pickering. 1998. Argumentation, the visual, and the possibility of refutation: An exploration. Argumentation 12: 79–93.

Langer, SK 1980 [1942]. Philosophy in a new key: A study in the symbolism of reason, rite and art. 3rd edition. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

Macano, F., and D. Walton. 2014. Emotive language in argumentation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Messaris, P. 1997. Visual persuasion: The role of images in advertising. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Messaris, P. 1994. Visual «literacy»: Image, mind, and reality. Boulder Co: Westview Press.

Murphy, J.M. 1994. Presence, analogy, and Earth in the balance. Argumentation and Advocacy 31: 1–16.

Perelman, C, Olbrechts-Tyteca, L. 1971 [1969]. The new rhetoric: A treatise on argumentation. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press.

Perlmutter, D. 1998. Photojournalism and foreign policy. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Sonesson, G. 2010a. Pictorial semiotics. In Encyclopedic dictionary of semiotics, eds. Sebeok, T., Danesi, M. 3. rev. and updated ed. Berlin and New York: De Gruyter Mouton.

Sonesson, G. 2010b. Iconicity strikes back: the third generation—Or why Eco still is wrong. In La sémiotique visuelle: nouveaux paradigmes Bilbliotèque VISIO 1, ed. Costantini, M. 247–270. L’Harmattan: Paris.

Tindale, C.W. 2004. Rhetorical argumentation. Principles of theory and practice. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage.

Toulmin, S. 1958. The uses of argument. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Zarefsky, D. 2014. Rhetorical perspectives on argumentation: Selected essays by David Zarefsky. Heidelberg/NewYork/Drodrecht/London: Springer.

Acknowledgments

My warm thanks to Tony Blair, Georges Roque and the anonymous reviewer for proposals and comments that have helped me improve this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kjeldsen, J.E. The Rhetoric of Thick Representation: How Pictures Render the Importance and Strength of an Argument Salient. Argumentation 29, 197–215 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10503-014-9342-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10503-014-9342-2