Abstract

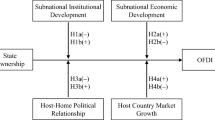

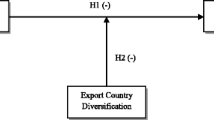

The emergence of marketized shareholders through corporate ownership reform and their impact on the foreign entry of emerging market firms is a critical but understudied issue. Our study investigates the effect of marketized state ownership on emerging market firms’ propensity to engage in foreign direct investment. We argue that firms with marketized state ownership may derive institutional competitive advantages from their dual responsiveness to shifting global market conditions and home government expectations which has a positive impact on their foreign investment decisions. However, such advantages are likely to vary in magnitude for firms with marketized state ownership at central and local levels of government due to different patterns of corporate restructuring. We predict that such ownership effects are contingent on firms’ affiliation to meso-level institutional structures such as state business groups which reallocate resources among members. Using a longitudinal sample of 973 Chinese publicly listed firms, we find empirical support for our arguments. Our research offers new insights on how emerging market multinationals may derive institutional advantages from pro-market reforms for overseas expansion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The majority of these shareholders consist of state entities such as government ministries, agencies, state asset management bureaus, state asset investment bureaus, military-owned companies, and industry companies in strategic sectors such as metallurgy, commodities, and other heavy industries with unreformed ownership. Such industry companies serve as critical policy instruments to support industrial output targets or national priorities.

For example, by 1993, within the defense sector, the Ministry of Energy Resources was converted into the China National Nuclear Corporation, the Ministry of Coal Industry and the Ministry of Electric Power Industry were both re-established, while the Ministry of Machine Building and Electronics Industry was divided into three separate entities—the Ministry of Electronics Industry, the Ministry of Machine Industry, and the China North Industries Corporation (NORINCO).

Originally founded as a subsidiary of the China Aerospace Science Technology Corporation and the China Aerospace Science and Industry Corporation, Zhongxing Telecommunications Equipment Corporation (ZTE) was transformed into a partially privatized firm and its main holding company has been 49 % privately held over the past decade. Institutional and foreign shareholders including Deutsche Bank, China Life Insurance Company, HKSCC Nominees, Agricultural Bank of China, JP Morgan Chase, PNB Paribas, and Sun Life Financial are consistently among its top 10 shareholders.

During the 1990s, control rights over many SOEs became increasingly decentralized to local state authorities (Huang, Li, Ma, & Xu, 2014). For example, in 1998 the State Council decreed that all 94 SOEs and their subsidiaries in the coal industry would be transferred from central to local jurisdiction. Following this transfer, provincial governments assumed fiscal responsibility for 3.2 million workers and 1.3 million retirees (Nie & Jiang, 2011). By the end of the 1990s, over 80 % of local SOEs were transformed into LMSOEs through partial privatization and reorganizations.

In a recent study, Shen, Jing, and Zhou (2012) found that central government expenditures fell from 40 % of the national budget in 1984 to 24 % in 2005, while local government expenditures grew from 45 % in 1981 to nearly 72 % in 1993, and then climbed to 75 % of the national budget by 2005 (Lu & Sun, 2013). Prior research has indicated that the 1994 national tax sharing reform led to a recentralization of tax revenues while expenditures were devolved to local governments without corresponding local revenue assignments (Man, 2011). Central government revenues surpassed local government revenues, rising from 23 % in 1992 to 52.3 % in 2005, while local government revenues dropped from 77 % to 48 % in 2005 (China Statistical Yearbook, 2013).

References

Ai, C., & Norton, E. 2003. Interaction terms in logit and probit models. Economic Letters, 80: 123–129.

Allison, P. A. 2012. Logistic regression using SAS: Theory & application. Cary: SAS Press.

Allison, P. D., & Waterman, R. P. 2002. Fixed effects negative binomial regression models. Sociological Methodology, 32(1): 247–265.

Barkema, H., & Vermeulen, F. 1997. What differences in the cultural backgrounds of partners are detrimental for international joint ventures?. Journal of International Business Studies, 28(4): 845–864.

Bhaumik, S. K., Driffield, N., & Pal, S. 2010. Does ownership structure of emerging market firms affect their outward FDI? The case of the Indian automotive and pharmaceutical sectors. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(3): 437–450.

Boeh, K. K., & Beamish, P. W. 2012. Time travel and the liability of distance in foreign direct investment: Location choice and entry mode. Journal of International Business Studies, 43(5): 525–535.

Boisot, M., & Child, J. 1996. From fiefs to clans and network capitalism: Explaining China’s emerging economic order. Administrative Science Quarterly, 41(4): 600–628.

Buckley, P. J., Clegg, L. J., Cross, A. R., Liu, X., Voss, H., & Zheng, P. 2007. The determinants of Chinese foreign direct investment. Journal of International Business Studies, 38: 499–518.

Cantwell, J., Dunning, J. H., & Lundan, S. 2010. An evolutionary approach to understanding international business activity: The co-evolution of MNEs and the institutional environment. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(4): 567–586.

Carney, M., & Gedajlovic, E. 2001. Corporate governance and firm capabilities: A comparison of managerial, alliance, and personal capitalisms. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 18(3): 335–354.

Carney, M., Gedajlovic, E., Heugens, P., Van Essen, M., & Oosterhout, J. 2011. Business group affiliation, performance, context, and strategy: A meta-analysis. Academy of Management Journal, 54(3): 437–460.

Chang, S. J. 2006. Business groups in East Asia: Post-crisis restructuring and new growth. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 23(4): 407–417.

Chang, S. J., & Hong, J. B. 2000. Economic performance of group-affiliated companies in Korea: Intragroup resource sharing and internal business transactions. Academy of Management Journal, 43(3): 429–448.

Chang, S. J., Chung, C. N., & Mahmood, I. P. 2006. When and how does business group affiliation promote firm innovation? A tale of two emerging economies. Organization Science, 17(5): 637–656.

Child, J., & Rodriguez, S. B. 2005. The internationalization of Chinese firms: A case for theoretical extension? Management and Organization Review, 1(3): 381–410.

Child, J., & Tsai, T. 2005. The dynamic between firm’s environmental strategies and institutional constraints in emerging economies: Evidence from China and Taiwan. Journal of Management Studies, 41(1): 95–125.

China Statistical Yearbook. 2013. Beijing: National Bureau of Statistics of China.

Chittoor, R., Sarkar, M. B., Ray, S., & Aulakh, P. S. 2009. Third-world copycats to emerging multinationals: Institutional changes and organizational transformation in the Indian pharmaceutical industry. Organization Science, 20(1): 187–205.

Christiansen, T., Lisheng, D., & Painter, M. 2008. Administrative reform in China’s central government—how much ‘learning from the West’?. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 74(3): 351–371.

Cui, L., & Jiang, F. 2012. State ownership effect on firms’ FDI ownership decisions under institutional pressure: A study of Chinese outward-investing firms. Journal of International Business Studies, 43(3): 264–284.

Dacin, M. T., Goodstein, J., & Scott, W. R. 2002. Institutional theory and institutional change: Introduction to the special research forum. Academy of Management Journal, 45(1): 45–56.

Delios, A., Zhi, J. W., & Zhou, N. 2006. A new perspective on ownership identities in China’s listed companies. Management & Organization Review, 2(3): 319–343.

DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. 1983. The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2): 147–160.

Dow, S., & McGuire, J. 2009. Propping and tunneling: Empirical evidence from Japanese keiretsu. Journal of Banking & Finance, 33(10): 1817–1828.

Dunning, J. 2004. Institutional reform, FDI and European transition economies. In R. Grosse (Ed.). International business and governments in the 21st century: 49–79. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ferris, S. P., Kim, K. A., & Kisabunnarat, P. 2003. The costs (and benefits?) of diversified business groups: The case of Korean chaebols. Journal of Banking & Finance, 27(2): 251–273.

Filatotchev, I., Strange, R., Piesse, J., & Lien, Y. C. 2007. FDI by firms from newly industrialized economies in emerging markets: Corporate governance, entry mode and location. Journal of International Business Studies, 38(4): 556–572.

Friedman, E., Johnson, S., & Mitton, T. 2003. Propping and tunneling. Journal of Comparative Economics, 31(4): 732–750.

Golapan, R., Vikram, N., & Seru, A. 2007. Affliated firms and financial support: Evidence from Indian business groups. Journal of Financial Economics, 86: 759–795.

Gupta, N. 2005. Partial privatization and firm performance. Journal of Finance, 60(2): 987–1015.

Hall, P. A., & Soskice, D. 2001. Varieties of capitalism: The institutional foundations of comparative advantage. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

He, J., Mao, X., Rui, O., & Zha, Z. 2013. Business groups in China. Journal of Corporate Finance, 22: 166–192.

Huang, Z., Li, L., Ma, G., & Xu, L. C. 2014. Local information and decentralization of state-owned enterprises in China: Hayek is right. Working paper from the Summer Institute of Finance Conference: http://www.cafr-sif.com/2014selectpapers/Hayek_May_19.pdf, Accessed Feb. 24, 2015.

Jeffersen, G., Jiang, R., & Tortorice, D. 2014. Restructuring China’s research institutes: Impacts on China’s research orientation and productivity. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2443546, Accessed Feb. 24, 2015.

Jefferson, G., & Su, J. 2006. Privatization and restructuring in China: Evidence from shareholding ownership, 1995–2001. Journal of Comparative Economics, 34(1): 146–166.

Jin, J., & Zou, H. F. 2005. Fiscal decentralization, revenue and expenditure assignments, and growth in China. Journal of Asian Economics, 16(9): 1047–1064.

Jin, H. H., Qian, Y. Y., & Weingast, B. R. 2005. Regional decentralization and fiscal incentives: Federalism, Chinese style. Journal of Public Economics, 89(9–10): 1719–1742.

Karaca-Mandic, P., Norton, E., & Dowd, B. 2012. Interaction terms in nonlinear models. Health Services Research, 47(1): 255–274.

Keister, L. A. 1998. Engineering growth: Business group structure and firm performance in China’s transition economy. American Journal of Sociology, 104(2): 404–440.

Keister, L. A. 2000. Chinese business groups: The structure and impact of interfirm relations during economic development. New York: Oxford University Press.

Khanna, P. 2012. The rise of hybrid governance. The Mckinsey Center for Government. http://www.mckinsey.com/features/government_designed_for_new_times/the_rise_of_hybrid_governance, Accessed Jun. 5, 2015.

Khanna, T., & Palepu, K. 1997. Why focused strategies may be wrong for emerging markets. Harvard Business Review, 75(4): 41–51.

Kim, H., & Hoskisson, H. E. 1996. Japanese governance systems: A critical review. In S. B. Prasad (Ed.). Advances in International Comparative Management: 165–189. Greenwich, CT: JAI.

Kim, H., Kim, H., & Hoskisson, R. E. 2010. Does market-oriented institutional change in an emerging economy make business group affiliated multinationals perform better? An institution-based view. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(7): 1141–1160.

Levinthal, D. A. 1997. Adaptation on rugged landscapes. Management Science, 43: 934–950.

Li, M. H., Cui, L., & Lu, J. Y. 2014. Varieties in state capitalism: Outward FDI strategies of central and local state-owned enterprises from emerging economy countries. Journal of International Business Studies, 45(8): 980–1004.

Li, Y., Sun, Y. F., & Liu, Y. 2006. An empirical study of SOEs’ market orientation in transitional China. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 23(1): 93–113.

Liao, L., Liu, B., & Wang, H. 2014. China’s secondary privatization: Perspectives from the split-share structure reform. Journal of Financial Economics, 113(3): 500–518.

Lin, W. T. 2014. How do managers decide to internationalization processes? The role of organizational slack and performance feedback. Journal of World Business, 49(3): 396–408.

Lin, L. W., & Milhaupt, C. J. 2013. We are the (national) champions: Understanding the mechanisms of state capitalism in China. Stanford Law Review, 65(4): 697–760.

Lin, W. T., Cheng, K. Y., & Liu, Y. 2009. Organizational slack and firm internationalization: A longitudinal study of high-technology firms. Journal of World Business, 44: 397–406.

Lin, J. Y., Tao, R., & Liu, M. 2005. Decentralization and local governance in the context of China’s transition. Perspectives, 6(2): 25–36.

Liu, G. S., & Woo, W. T. 2001. How will ownership in China’s industrial sector evolve with WTO accession?. China Economic Review, 12(2): 137–161.

Lu, J., & Ma, X. 2008. The contingent value of local partners’ business group affiliations. Academy of Management Journal, 51(2): 295–314.

Lu, Y., & Sun, T. 2013. Local government financing platforms in China: A fortune or misfortune? IMF working paper no. WP/13/243, International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC.

Luo, Y., Sun, J., & S., L. W. 2011. Emerging economy copycats: Capability, environment and strategy. Academy of Management Perspectives, 25(2): 37–56.

Luo, Y., Xue, Q., & Han, B. 2010. How emerging market governments promote outward FDI: Experience from China. Journal of World Business, 45(1): 68–79.

Ma, X. F., Yao, X. T., & Xi, Y. M. 2006. Business group affiliation and firm performance in a transition economy: A focus on ownership voids. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 23(4): 467–483.

Man, J. Y. 2011. Local public finance in China: An overview. In J. Y. Man & Y. H. Hong (Eds.). China’s local public finance in transition: 3–17. Cambridge: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

Martin, X. 2014. Commentary on institutional advantage. Global Strategy Journal, 4: 55–69.

Meyer, K., Ding, Y., Li, J., & Zhang, H. 2014. Overcoming distrust: How state-owned enterprises adapt their foreign entries to institutional pressures abroad. Journal of International Business Studies, 45(8): 1005–1028.

Mussachio, A., Lazzarini, S. G., & Aguilera, R. V. 2015. New varieties of state capitalism: Strategic and governance implications. Academy of Management Perspectives, 29(1): 115–131.

Nee, V. 1992. Organizational dynamics of market transition: Hybrid forms, property rights, and mixed economy in China. Administrative Science Quarterly, 37(1): 1–27.

Nie, H. H., & Jiang, M. J. 2011. Coal Mine Accidents and Collusion between Local Governments and Firms: Evidence from Provincial Level Panel Data in China. Economic Research Journal, 6: 146–156 (In Chinese).

Nohria, N., & Gulati, R. 1996. Is slack good or bad for innovation?. Academy of Management Journal, 39: 1245–1264.

OECD. 2012. The governance of mixed-ownership enterprises in Latin America. http://www.oecd.org/daf/ca/SecondMeetingLatinAmericanSOENetworkMixedOwnership.pdf, Accessed Feb. 24, 2015.

Palepu, K. G. 1986. Predicting takeover targets. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 8: 3–35.

Park, S. H., Li, S., & Tse, D. K. 2006. Market liberalization and firm performance during China’s economic transition. Journal of International Business Studies, 37(1): 127–147.

Pedersen, T., & Thomsen, S. 2003. Ownership structure and value of the largest European firms: The importance of owner identity. Journal of Management and Governance, 7: 22–55.

Peng, M. W., Sun, S. L., & Tan, W. 2008. Competing on scale or scope? Lessons from Chinese firms’ internationalization. In I. Alon & J. R. Mclntyre (Eds.). Globalization of Chinese enterprises: 77–97. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Peng, M. W., Tan, J., & Tong, T. W. 2004. Ownership types and strategic groups in an emerging economy. Journal of Management Studies, 41(7): 1105–1129.

Poczter, S. 2014. The agency mechanism of privatization. Evidence from Indonesia. Cornell University working paper: http://dyson.cornell.edu/people/profiles/poczter/Draft_080314-V3tables.pdf?abstract_id=2403509, Accessed Feb. 24, 2015.

Rabe-Hesketh, S., & Skrondal, A. 2012. Multilevel and longitudinal modeling using STATA. College Station: STATA Press.

Ramasamy, B., Yeung, M., & Laforet, S. 2012. China’s outward foreign direct investment: Location choice and firm ownership. Journal of World Business, 47(1): 17–25.

Rhee, J. H. R., & Cheng, J. L. C. 2002. Foreign market uncertainly and incremental international expansion: The moderating effect of firm, industry, and host country factors. Management International Review, 42(4): 419–439.

Shen, C., Jin, J., & Zhou, H. 2012. Fiscal decentralization in China: History, impact, challenges and next steps. Annals of Economics and Finance, 13(1): 1–51.

Steinfeld, E. 1998. Forging reform in China: The fate of state-industry. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sullivan, D. 1994. Measuring the degree of internationalization of a firm. Journal of International Business Studies, 25(2): 325–342.

Tallman, S., & Li, J. T. 1996. Effects of internationalization: Japanese FDI strategies in Asia-Pacific. Academy of Management Journal, 39(1): 179–196.

Thomsen, S., & Pedersen, T. 2000. Ownership structure and economic performance in the largest European companies. Strategic Management Journal, 21: 689–705.

Tu, H. S., Kim, S. Y., & Sullivan, S. E. 2002. Global strategy lessons from Japanese and Korean business groups. Business Horizons, 45(2): 39–46.

Vuong, Q. H. 1989. Likelihood ratio tests for model specification and non-nested hypotheses. Econometrica, 57: 307–333.

Wang, C., Hong, J., Kafouros, M., & Wright, M. 2012. Exploring the role of government involvement in outward FDI from emerging economies. Journal of International Business Studies, 43(7): 655–676.

Xia, J., Boal, K., & Delios, A. 2009. When experience meets national institutional environmental change: Foreign entry attempts of U.S. firms in the central and eastern European region. Strategic Management Journal, 30: 1286–1309.

Yiu, D. W. 2011. Multinational advantages of Chinese business groups: A theoretical exploration. Management and Organization Review, 7(2): 249–277.

Yusuf, S., & Nabeshima, K. 2008. Two decades of reform: The changing organization dynamics of Chinese industrial firms. In J. Logan (Ed.). Urban China in transition: 27–47. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Zattoni, A., Pedersen, T., & Kumar, V. 2009. The performance of group-affiliated firms during institutional transition: A longitudinal study of Indian firms. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 17(4): 510–523.

Zhang, W. K. 2011. The emergence of China’s mixed-ownership enterprises and their corporate governance. Unpublished PhD thesis, Department of Economics and Finance, Brunel University: http://bura.brunel.ac.uk/bitstream/2438/5920/1/FulltextThesis.pdf, Accessed Feb. 24, 2015.

Acknowledgments

This paper was presented at the 4rd Copenhagen Conference on Outward Investment from Emerging Economies. We are especially grateful to the guest editors and three anonymous reviewers. We would like to thank Ari Kokko, Bersant Hodari, Jing Li, Klaus Meyer, and Peter Gammeltoft for their encouragement and feedback. We gratefully acknowledge the National Science Foundation of China (#71172020; #71472010; #71472038) and the Australian Research Council (DE130100860) for their financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

For this type of study formal consent is not required.

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Appendix 2: Coding methods for ownership variables of Chinese publicly listed firms

During the first wave of ownership reform, many large SOEs went public to raise minority tradable shares by selling them to private actors while the state retained majority control over non-tradable shares (Liao, Liu, & Wang, 2014). While this initial ownership classification system is nominally demarcated by the share transaction regulations set forth by the China Securities Regulatory Commission, it does not provide a clear link to the actual ownership identities of different shareholders. According to Delios et al. (2006: 325), “we can clearly see that state-owned shares (guoyou gu) consist of two parts: state shares (guojia gu) and state-owned legal person shares (guoyou faren gu). Yet, these two parts rest in two different categories in the official classification. Even this simple description reveals a problem in the content validity as it relates to the identities of shareholders in the official classification scheme.” To verify the shareholding identities of Chinese listed firms, Delios et al. (2006) proposed a new classification system by identifying shareholders based on substantive criteria relating to their functional and strategic characteristics. Reflecting the tangible impact of ownership reforms, the category of marketized state shareholding was established in the new classification system to complement the non-marketized state shareholding category, while newly privatized security companies and investment funds were added to the existing category of private firms.

Given the complexity of ownership classification for Chinese listed firms, we took rigorous steps when coding the independent variable for our study. First, shareholders were assigned into one of the 16 shareholding subcategories as listed in Appendix 1. Then they were sorted into the three broad ownership categories. We separated private shareholders, and re-categorized marketized and non-marketized state shareholders. Marketized state shareholders were identified based on whether they had successfully engaged in shareholding diversification under the joint-stock reform through the introduction of institutional, private, or foreign owners at the holding group level (Li et al., 2006).

Firms which had diversified their shareholding by transferring no less than 5 % of their total shares to individual non-state block shareholders qualified under this requirement (Zhang, 2011). We applied this procedure since block shareholders do not typically hold large blocks of shares for the purposes of trading them in the secondary market. They represent key stakeholders that serve the role of strategic investors with an interest in improving the long-term managerial performance and corporate governance of their invested firms. In practice, firms with diversified corporate ownership often have multiple non-state minority block shareholders and a controlling state majority owner which typifies the vast number of listed SOEs falling under this category.

In our coding process, we found that several industry companies reorganized from former ministries such as ZTE had introduced mixed private ownership by the early 2000s. Meanwhile, military owned companies such as NORINCO (China North Industries Corporation) remained 100 % controlled by the government and were not subject to shareholding diversification. This led us to observe some exceptions to the Delios et al.’s (2006) classification scheme.

Another category of firms which had not received much attention in this classification system were university-run science and technology (S&T) enterprises which are majority owned by a university holding company reporting to the Ministry of Education but are founded by university professors turned entrepreneurs. To encourage their managerial and profit incentives, minority shares in these companies are often allocated to these academic managers. A recent empirical study by Jeffersen, Jiang, and Tortorice (2014) on the restructuring of Chinese research institutes found that university-run S&T firms had substantially augmented their non-government revenues and patent productivity after shifting their reliance away from government grants.

Due to their strong commercial orientation, mixed-ownership and professional management, these firms are distinguished from government research institutes and universities which are categorized as non-marketized state-owned firms by Delios et al. (2006). Lastly we separated marketized state-owned firms into CMSOEs and LMSOEs based on their level of government affiliation. We repeated this coding process for each year of our sample to capture changes in shareholding identities associated with the ongoing process of corporate ownership reform.

In addition to shareholding diversification, marketized SOEs have also undergone significant corporate governance reforms which coincide with their ownership transformation and restructuring. In the vast majority of cases, ownership reform through the introduction of non-state strategic investors has been accompanied by the adoption of new governance practices relating to the appointment of senior managers, operational autonomy, and disclosure which were brought in by those investors. Following a survey of 950 Chinese firms, Zhang (2011) found that after restructuring, the majority of marketized SOEs had adopted shareholding covenants between new strategic investors and the government shareholders which govern the conditions for establishing the shareholding proportion, the distribution of voting rights, the composition of the board of directors, and exit arrangements.

We coded marketized state shareholders based on their shareholding reform history and the corporate governance improvements described above. Due to the transitional nature of ownership reform, some firms which appeared to belong to one shareholding subcategory may also fit into another category, especially when the ownership composition of the holding company changed and state shares were transferred to legal person and private shareholders. Therefore, extensive we made extensive research to investigate available public information on the shareholding structure of these firms to reach clarification.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Li, M.H., Cui, L. & Lu, J. Marketized state ownership and foreign expansion of emerging market multinationals: Leveraging institutional competitive advantages. Asia Pac J Manag 34, 19–46 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-015-9436-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-015-9436-x