Abstract

In the aftermath of high-profile incidents involving Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC) in North America, there is a growing awareness of the pervasiveness of systemic racism and the role that agencies play in perpetuating racism and racial inequities. In the child and youth mental health sector, the journey to improving racial equity is impeded by a lack of consistent frameworks or guidelines. In this commentary, we explore five domains of organizational practices that are prominent in the literature and support diverse clients, communities and staff, including: (1) organizational leadership and commitment, (2) inter-organizational and multisectoral partnerships, (3) workforce diversity and development, (4) client and community needs and engagement, and (5) continuous improvement. As we highlight these domains, we urge researchers, policy makers, and child and youth mental health service providers to work together to advance racial equity in meaningful ways.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Heightened racial tensions in North America have shone a light on systemic racism and inequities faced by racialized communities, defined as those “designated as being part of a particular race and on that basis subjected to differential and/or unequal treatment” (Calgary Anti-Racism Education, n.d., para. 2). Within the context of North America, racialized communities tend to be Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC). In the United States, there have been several recent high-profile cases of BIPOC being killed by police, as in the case of George Floyd, and instances of protests on race turning violent, like the Charlottesville protest in 2017. Canada, with its ideals and values rooted in social equity, is often seen as a haven for equity, diversity, and inclusion. Likewise, the Canadian health system is a source of pride for many; a system that does not discriminate based on age, race, or socio-economic status (Martin et al., 2018). But Canada is not immune to racism.

There are many examples of racism in Canada, both historical and current. Recently, the discovery of unmarked graves of 215 Indigenous children who died due to abuse and neglect at the Kamloops Indian Residential School in British Columbia (Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc, 2021) shook the country and served as a stark reminder of the impact of systemic racism. For Indigenous communities, these findings only confirmed what had been known for years; that for decades the Canadian government tore families apart, forcibly sending children to residential schools across the country in an effort to “take the Indian out of the child” (Fine, 2015), or assimilate children to Canadian society. In these schools, they were stripped of their traditional hair and dress, forbidden to speak their native language, and often physically and sexually abused (Miller, 2021). The residential school system was one of many systems of oppression that has neglected and affronted the strengths and rights of Indigenous communities (Métis Nation of Ontario, 2021; Wilk et al., 2017).

Little research has been conducted on the health inequities of BIPOC children and youth in Canada (Nestel, 2012). Even less research has been conducted on organizational practices aimed at improving racial equity (Abramovitz & Blitz, 2015). What we know affirms that the Canadian health system does, in fact, discriminate. BIPOC youth in Canada face significantly more barriers to care (Fante-Coleman & Jackson-Best, 2020) and are more likely to mistrust the health system due to historical trauma, resulting in underutilization of health services and poorer health outcomes than their White counterparts (Li & Galea, 2020). In light of these existing barriers, there is widespread concern that COVID-19 has disproportionally impacted the mental health of BIPOC children and youth (Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario, 2021; Mental Health Commission of Canada, 2020). This is a well-founded concern, as research confirms that COVID-19 has disproportionally impacted the mental health of BIPOC adults (Canadian Mental Health Association et al., 2020), a result of a tangled web of factors from poor housing conditions, precarious labour, and racism.

As awareness grows, many community-based agencies are reflecting on their role in perpetuating racism and racial inequities and how they can be part of the solution. As agencies begin their journey, they may consider whether they are underserving some and overserving others, if their racialized staff are being adequately supported or if their services are equitable. In the child and youth mental health sector, there is no consistent strategy or framework to guide agencies in this journey. This can leave agencies feeling overwhelmed and unequipped to begin work in this area.

Informed by implementation science and drawing from the limited research in child and youth mental health and related sectors, we highlight organizational practices that support efforts in addressing racial equity across five domains: (1) organizational leadership and commitment, (2) inter-organizational and multisectoral partnerships, (3) workforce diversity and development, (4) client and community needs and engagement, and (5) continuous improvement. We briefly review these domains and outline areas for further research.

Organizational Practices to Inform Racial Equity Approaches

The literature on organizational practices to improve racial equity is centered on strong leadership and a public commitment to anti-racism, such as aligning the vision, policies, and resources of the organization (Gill et al., 2018; South et al., 2020). Organizational progress is positively associated with leaders who provide positive feedback, express interest, and engage in racial equity training (Abramovitz & Blitz, 2015). In line with its role in driving change, leadership has also been highlighted in the following themes throughout the literature.

A second area that agencies need to attend to when advancing racial equity is working alongside other community organizations. Agencies can call upon the knowledge and connections of other community-based organizations to improve outreach, access, and coordination of care to racialized communities as well as facilitate system-level changes that address social determinants of health (Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, 2018; Canadian Mental Health Association Ontario, 2017; Castillo et al., 2019). Research examining cross-sectoral collaborations with the education sector and community-based partnerships with churches demonstrate improved mental health outcomes for youth and broader outcomes for racialized communities by overcoming stigma, facilitating early identification of mental health needs, and increasing points of access to mental health care (Hankerson et al., 2018; Knopf et al., 2016; Parra-Cardona et al., 2021).

The third area relates to workforce diversity and development, which requires the engagement of racialized staff. Most research regarding organizational practices to achieve equitable outcomes focuses on recruiting more diverse workforces and training staff in cultural responsiveness and anti-racism. There is merit in these efforts; diverse workforces that are representative of the communities they serve have the knowledge and experience to understand and address the needs of racialized communities (O’Keefe et al., 2021) and overcome mistrust that is borne from a history of systemic racism and negative experiences and outcomes (Aden et al., 2020). In addition, recent training programs with a focus on racial equity have shown promise in reducing negative bias (Sukhera et al., 2020) and implementing organizational changes to improve racial equity (Browne et al., 2018; Varcoe et al., 2019) in healthcare settings.

The fourth domain relates to engaging with racialized clients and with racialized communities. Literature points to the opportunity for enhanced collaborations with community-based organizations to enhance racial equity at the organizational level. In addition, quality youth and family engagement can more directly incorporate the voices of racialized communities by collaborating and co-developing service, organizational and system level initiatives with them as equal partners (Ontario Centre of Excellence for Child and Youth Mental Health, 2021; Stone et al., 2021). In addition, theoretical frameworks for providing anti-racist mental healthcare emphasizes the importance of providing assessments and services that are culturally and linguistically appropriate to address the needs of communities with unique histories and cultures (Callejas et al., 2021; Cénat, 2020). Important work is taking place to establish culturally responsive care, such as frameworks for providing culturally responsive and strengths-based services to Indigenous communities (Assembly of First Nations & Health Canada, 2015).

Lastly, the fifth domain relates to continuous improvement which includes established procedures to evaluate the work being done over time and identify areas for improvement (The Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2014; Ontario Human Rights Commission, 2009). Recent literature indicates that confidential race-based demographic data from staff and clients that is centered in racial equity can inform agencies of the unique needs and strengths of their own organization as well as the communities they serve (Actionable Intelligence for Social Policy & University of Pennsylvania, 2020). Frameworks that apply an equity lens to continuous improvement strategies highlight the importance of accountability practices, such as engaging impacted communities for feedback and interpreting data, to ensure that efforts are not perpetuating inequity and gain valuable feedback for improvements (Metz et al., 2021).

There are opportunities for further and improved research to expand our understanding of how agencies can improve racial equity for racialized children, youth, families, and staff. Potential areas of future research include understanding the role of the Board of Directors, isolating and evaluating behavioural and organizational outcomes of racial equity focused training, and identifying effective strategies to retain and learn from racialized staff. Based on the experiences of agencies, it is crucial to address barriers of funding and agency capacity.

Where Do We Go From Here?

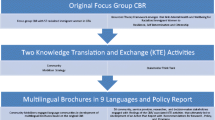

The Ontario Centre of Excellence for Child and Youth Mental Health and Children's Mental Health Ontario have embarked on a journey towards advancing racial equity in the child and youth mental health sector in Ontario, Canada. This journey began with an exploratory review of the literature and will continue with a scan of organizational practices that support racial equity in child and youth mental health agencies across the province. BIPOC leaders, service providers, youth, and family members have been instrumental in supporting our agencies to undertake these efforts. Our aim is that this scan will contextualize published literature, as presented in this article. By applying an implementation science and quality improvement lens to our inquiry, we aim to avoid traditional research and practice-based gaps, whereby evidence exists but is not reflective of what occurs in practice.

We seek to understand implications for those delivering mental health services and to better understand agencies’ efforts in the five domains identified in this paper. These domains can be understood as the core elements in an implementation science approach. Training staff on anti-racism and collecting race-based data is not sufficient to advance racial equity. We have implementation science frameworks that ensure efforts are sustained within our organizations. Further research into how activities within these five domains significantly advance racial equity and improve mental health outcomes for racialized children and youth are needed. To make significant and sustained progress and ensure children and youth from varied cultural, ethnic and linguistic backgrounds receive the best care possible, we call on researchers, policy makers, and child and youth mental health service providers to work together to advance racial equity in meaningful ways.

References

Abramovitz, M., & Blitz, L. V. (2015). Moving toward racial equity: The undoing racism workshop and organizational change. Race and Social Problems, 7, 97–110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12552-015-9147-4

Actionable Intelligence for Social Policy and University of Pennsylvania. (2020). A toolkit for centering racial equity throughout data integration. https://www.aisp.upenn.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/AISP-Toolkit_5.27.20.pdf

Aden, H., Oraka, C., & Russell, K. (2020). Mental health of Ottawa’s Black community. Ottawa Public Health. https://www.ottawapublichealth.ca/en/reports-research-and-statistics/resources/Documents/MHOBC_Technical-Report_English.pdf

Assembly of First Nations & Health Canada. (2015). First Nations mental wellness continuum framework (Health Canada Publication No. 140358). Health Canada. https://thunderbirdpf.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/24-14-1273-FN-Mental-Wellness-Framework-EN05_low.pdf

Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO). (2018). Collaborations between health systems and community-based organizations to address behavioral health. https://www.astho.org/Clinical-to-Community-Connections/Documents/Collaborations-Between-Health-Systems-and-Community-Based-Organizations-to-Address-Behavioral-Health/01-08-19/

Browne, A. J., Varcoe, C., Ford-Gilboe, M., Wathen, C. N., Smye, V., Jackson, B. E., Wallace, B., Pauly, B., Herbert, C. P., Lavoie, J. G., Wong, S. T., & Garneau, A. B. (2018). Disruption as opportunity: Impacts of an organizational health equity intervention in primary care clinics. International Journal for Equity in Health. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-018-0820-2

Calgary Anti-Racism Education. (n.d.). Racialization. https://www.aclrc.com/racialization

Callejas, L. M., Perez Jr., G., & Limon, F. J. (2021). Community-defined evidence as a framework for equitable implementation. Stanford Social Innovation Review (Suppl.), 25–26. https://ssir.org/articles/entry/community_defined_evidence_as_a_framework_for_equitable_implementation

Canadian Mental Health Association Ontario. (2017). Advancing equity in mental health: An action framework. https://ontario.cmha.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/PPE-0001-Advancing-Equity-in-Mental-Health-2.pdf

Canadian Mental Health Association, University of British Columbia, Maru/Matchbox, Mental Health Foundation, & the Agenda Collaborative. (2020). COVID-19 effects on the mental health of vulnerable populations. Canadian Mental Health Association. https://cmha.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/EN_UBC-CMHA-COVID19-Report-FINAL.pdf

Castillo, E. G., Ijadi-Maghsoodi, R., Shadravan, S., Moore, E., Mensah, M. O., Docherty, M., Aguilera Nunez, M. G., Barcelo, N., Goodsmith, N., Halpin, L. E., Morton, I., Mango, J., Montero, A. E., Rahmanian Koushkaki, S., Bromley, E., Chung, B., Jones, F., Gabrielian, S., Gelberg, L., … Wells, K. B. (2019). Community interventions to promote mental health and social equity. Current Psychiatry Reports. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-019-1017-0

Cénat, J. M. (2020). How to provide anti-racist mental health care. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(11), 929–931. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30309-6

Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario. (2021, May 19). Kids are in crisis: Canada’s top advocates and experts unite to declare #codePINK [Press release]. https://www.cheo.on.ca/en/news/kids-are-in-crisis-canada-s-top-advocates-and-experts-unite-to-declare-codepink.aspx

Fante-Coleman, T., & Jackson-Best, F. (2020). Barriers and facilitators to accessing mental healthcare in Canada for Black youth: A scoping review. Adolescent Research Review, 5, 115–136. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-020-00133-2

Fine. S. (2015, May 28). Chief Justice says Canada attempted ‘cultural genocide’ on Aboriginals. Globe and Mail. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/chief-justice-says-canada-attempted-cultural-genocide-on-aboriginals/article24688854/

Gill, G. K., McNally, M. J., & Berman, V. (2018). Effective diversity, equity, and inclusion practices. Healthcare Management Forum, 31(5), 196–199. https://doi.org/10.1177/0840470418773785

Hankerson, S. H., Wells, K., Sullivan, M. A., Johnson, J., Smith, L., Crayton, L. S., Miller-Sethi, F., Brooks, C. T., Rule, A., Ahmad-Llewellyn, J., Rhem, D., Porter, X., Croskey, R., Simpson, E., Butler, C., Roberts, S., James, A., & Jones, L. (2018). Partnering with African American churches to create a community coalition for mental health. Ethnicity and Disease, 28(2), 467–474. https://doi.org/10.18865/ed.28.S2.467

Knopf, J. A., Finnie, R. K. C., Peng, Y., Hahn, R. A., Truman, B. I., Vernon-Smiley, M., Johnson, V. C., Johnson, R. L., Fielding, J. E., Muntaner, C., Hunt, P. C., Phyllis Jones, C., & Fullilove, M. T. (2016). School-based health centers to advance health equity: A community guide systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 51(1), 114–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2016.01.009

Li, Y., & Galea, S. (2020). Racism and the COVID-19 epidemic: Recommendations for health care workers. American Journal of Public Health, 110(7), 956–957. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2020.305698

Martin, D., Miller, A., Quesnel-Vallee, A., Caron, N. R., Vissandjee, B., & Marchildon, G. P. (2018). Canada’s universal health-care system: Achieving its potential. The Lancet, 391(10131), 1718–1735. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30181-8

Mental Health Commission of Canada. (2020). Lockdown life: Mental health impacts of COVID-19 on youth in Canada. https://www.mentalhealthcommission.ca/sites/default/files/2021-02/lockdown_life_eng.pdf

Métis Nation of Ontario. (2021, May 31). Statement from Métis Nation of Ontario on recent revelations from Kamloops Indian Residential School [Press release]. https://www.metisnation.org/news/statement-from-mno-on-recent-revelations-from-kamloops-indian-residential-school/

Metz, A., Woo, B., & Loper, A. (2021). Equitable implementation at work. Stanford Social Innovation Review (Suppl.), 29–31. https://ssir.org/articles/entry/equitable_implementation_at_work

Miller, J. R. (2021). Residential schools in Canada. The Canadian Encyclopedia. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/residential-schools

Nestel, S. (2012). Colour coded health care: The impact of race and racism on Canadians’ health. Wellesley Institute. https://www.wellesleyinstitute.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/Colour-Coded-Health-Care-Sheryl-Nestel.pdf

O’Keefe, V. M., Cwik, M. F., Haroz, E. E., & Barlow, A. (2021). Increasing culturally responsive care and mental health equity with Indigenous community mental health workers. Psychological Services, 18(1), 84–92. https://doi.org/10.1037/ser0000358

Ontario Centre of Excellence for Child and Youth Mental Health. (2021). Quality standard for youth engagement. www.cymh.ca/ye_standard

Ontario Human Rights Commission (OHRC). (2009). Count me in! Collecting human rights-based data. http://www3.ohrc.on.ca/sites/default/files/attachments/Count_me_in%21_collecting_human_rights_based_data.pdf

Parra-Cardona, R., Zapata, O., Emerson, D. G., Garcia, D., & Sandoval-Pliego, J. (2021). Faith-based organizations as leaders of implementation. Stanford Social Innovation Review (Suppl.), 21–24. https://ssir.org/articles/entry/faith_based_organizations_as_leaders_of_implementation#bio-footer

South, E. C., Butler, P. D., & Merchant, R. M. (2020). Toward an equitable society: Building a culture of antiracism in health care. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 130(10), 5039–5041. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI141675

Stone, W., Billings, M., & Boxx, R. (2021). Community takes the wheel. Stanford Social Innovation Review (Suppl.), 11–14. https://ssir.org/articles/entry/community_takes_the_wheel

Sukhera, J., Watling, C. J., & Gonzalez, C. M. (2020). Implicit bias in health professions: From recognition to transformation. Academic Medicine, 95(5), 717–723. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000003173

The Anne E. Casey Foundation. (2014). Race equity and inclusion action guide. Embracing racial equity: 7 steps to advance and embed race equity and inclusion within your organization. https://www.aecf.org/resources/race-equity-and-inclusion-action-guide

Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc (Kamloops Indian Band). (2021, May 27). Remains of children of Kamloops Residential School discovered [Press release]. https://tkemlups.ca/remains-of-children-of-kamloops-residential-school-discovered/

Varcoe, C., Bungay, V., Browne, A. J., Wilson, E., Wathen, C. N., Kolar, K., Perrin, N., Comber, S., Garneau, A. B., Byres, D., Black, A., & Price, E. R. (2019). EQUIP emergency: Study protocol for an organizational intervention to promote equity in health care. BMC Health Services Research. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4494-2

Wilk, P., Maltby, A., & Cooke, M. (2017). Residential schools and the effects on Indigenous health and well-being in Canada: A scoping review. Public Health Reviews. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40985-017-0055-6

Funding

This work was funded by the Ontario Centre of Excellence for Child and Youth Mental Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ED and JK conceptualized the commentary. GL performed the literature search. All authors drafted, revised and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lucente, G., Kurzawa, J. & Danseco, E. Moving Towards Racial Equity in the Child and Youth Mental Health Sector in Ontario, Canada. Adm Policy Ment Health 49, 153–156 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-021-01153-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-021-01153-3