Abstract

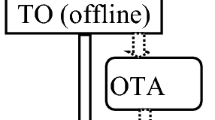

With the rapid development of e-commerce, an increasing number of online travel agencies (OTA) have combined traditional channels with opaque channels to maximise revenue, by implementing a price-discrimination strategy. Based on posted-price (PP) mechanism, this study reviews variable opaque products (VOPs) that allow travellers to change the opacity of an opaque channel to avoid unsatisfactory hotels. The purpose of the study is to determine how to optimise OTA revenue. Using a variation of the Hotelling model, this study examines the behaviour of travellers whose reservation values are relatively low. Additionally, we determine the optimal pricing strategy, which changes with the opacity of the opaque channel. The study shows that when the proportion of high-value travellers is low, OTA should decrease the price of transparent hotels; however, when the proportion is high, OTA should set a high price in the traditional channel, so that high-value travellers buy in the traditional channel, while low-value travellers buy in the opaque channel. And when the valuations differ greatly, OTA tend to increase the price of transparent hotels. Finally, when the number of travellers is constant, revenue increases when hotels increase, though there is an upper limit, and revenue decreases when the market expands. The results provide significant implications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Anderson, C. K., & Xie, X. (2014). Pricing and market segmentation using opaque selling mechanisms. European Journal of Operational Research, 233(1), 263–272.

Bai, S., Yan, Z., & Liu, L. (2015). Optimizing variable opaque product design in E-commerce based on blind booking. Procedia Computer Science, 60(1), 1676–1686.

Chen, H. S., & Yuan, J. (2016). A journey to save on travel expenses: The intentional buying process of consumers on opaque-selling websites. Journal of Hospitality Marketing and Management, 25(7), 820–840.

Chen, H. T., & Yuan, J. (2014). Blind savings or unforeseen costs? How consumers perceive the benefits and risks of using opaque travel selling Web sites. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 20(4), 309–322.

Chen, R. R., Gal-Or, E., & Roma, P. (2014). Opaque distribution channels for competing service providers: Posted price vs name-your-own-price mechanisms. Operations Research, 62(4), 733–750.

Dana, J. D. (1999). Using yield management to shift demand when peak time is unknown. Rand Journal of Economics, 30(3), 456–474.

Fan, X., Zhao, W., Zhang, T., & Yan, E. (2020). Mobile payment, third-party payment platform entry and information sharing in supply chains. Annals of Operations Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-020-03749-8

Fay, S. (2008). Selling an opaque product through an intermediary: The case of disguising one’s product. Journal of Retailing, 84(1), 59–75.

Fay, S., & Xie, J. (2008). Probabilistic goods: A creative way of selling products and services. Marketing Science, 27(4), 674–690.

Fay, S., & Xie, J. (2015). Timing of product allocation: Using probabilistic selling to enhance inventory management. Management Science, 61(2), 474–484.

Fay, S., Xie, J., & Feng, C. (2015). The effect of probabilistic selling on the optimal product mix. Journal of Retailing, 91(3), 451–467.

Feng, B., Liu, W., & Mao, Z. (2018). Use of opaque sales channels in addition to traditional channels by service providers. International Journal of Production Research, 56(10), 3369–3383.

Feng, B., Mao, Z., & Li, H. (2019). Choices for competing service providers with heterogeneous customers: Traditional versus opaque sales modes. Omega. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omega.2019.102133

Gale, I. L., & Holmes, T. J. (1993). Advance-purchase discounts and monopoly allocation of capacity. American Economic Review, 83(1), 135–146.

Gönsch, J., & Steinhardt, C. (2013). Using dynamic programming decomposition for revenue management with opaque products. Business Research, 6(1), 94–115.

Granados, N., Gupta, A., & Kauffman, R. J. (2008). Designing online selling mechanisms: Transparency levels and prices. Decision Support Systems, 45(4), 729–745.

Granados, N., Han, K., & Zhang, D. (2017). Demand and revenue impacts of an opaque channel: Evidence from the airline industry. Production and Operations Management, 27(11), 2010–2024.

Huang, T., & Yu, Y. (2014). Sell probabilistic goods? A behavioral explanation for opaque selling. Marketing Science, 33(5), 743–759.

Huang, X., Sosic, G., & Kersten, G. (2017). Selling through priceline? on the impact of name-your-own-price in competitive market. IIE Transactions, 49(3), 304–319.

Jerath, K., Netessine, S., & Veeraraghavan, S. K. (2010). Revenue management with strategic customers: Last-minute selling and opaque selling. Management Science, 56(3), 430–448.

Jiang, Y. (2007). Price discrimination with opaque products. Journal of Revenue and Pricing Management, 6(2), 118–134.

Jiang, Z. Z., Zhao, J., Yi, Z., & Zhao, Y. (2020). Inducing information transparency: The roles of gray market and dual-channel. Annals of Operations Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-020-03719-0

Lee, M., Khelifa, A., Garrow, L. A., Bierlaire, M., & Post, D. (2012). An analysis of destination choice for opaque airline products using multidimensional binary logit models. Transportation Research Part a: Policy and Practice, 46(10), 1641–1653.

Li, D., & Pang, Z. (2017). Dynamic booking control for car rental revenue management: A decomposition approach. European Journal of Operational Research, 256(3), 850–867.

Li, T., Xie, J., Lu, S., & Tang, J. (2016). Duopoly game of callable products in airline revenue management. European Journal of Operational Research, 254(3), 925–934.

Li, Q., Li, B., Chen, P., & Hou, P. (2017). Dual-channel supply chain decisions under asymmetric information with a risk-averse retailer. Annals of Operations Research, 257(1–2), 423–447.

Li, Q., Tang, C. S., & Xu, H. (2019). Mitigating the double-blind effect in opaque selling: inventory and information. Production and Operations Management. https://doi.org/10.1111/poms.13087

Mao, Z., Liu, W., & Feng, B. (2018). Opaque distribution channels for service providers with asymmetric capacities: Posted-price mechanisms. International Journal of Production Economics, 215(1), 112–120.

Post, D. (2010). Variable opaque products in the airline industry: A tool to fill the gaps and increase revenues. Journal of Revenue and Pricing Management., 9(4), 292–299.

Post, D., & Spann, M. (2012). Improving airline revenues with variable opaque products: “blind booking” at germanwings. Interfaces, 42(4), 329–338.

Raúl, B., & Walker, J. L. (2011). Latent temporal preferences: An application to airline travel. Transportation Research Part A Policy & Practice, 45(9), 880–895.

Salop, S. (1979). Monopolistic competition with outside goods. The Bell Journal of Economics, 10(1), 141–156.

Shapiro, D., & Shi, X. (2008). Market segmentation: The role of opaque travel agencies. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 17(4), 803–837.

Strauss, A., Klein, R., & Steinhardt, C. (2018). A review of choice-based revenue management: Theory and methods. European Journal of Operational Research, 271(2), 375–387.

Tsamboulas, D. A., & Nikoleris, A. (2008). Passengers’ willingness to pay for airport ground access time savings. Transportation Research Part A, 42(10), 1274–1282.

Xiao, L., Chen, S., & Huang, S. (2020). Observability of retailer demand information acquisition in a dual-channel supply chain. Annals of Operations Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-020-03629-1

Xie, X., Anderson, C. K., & Verma, R. (2017). Customer preferences and opaque intermediaries. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 58(4), 342–353.

Xing, X. H., Hu, Z. H., & Luo, W. P. (2020). Using evolutionary game theory to study governments and logistics companies’ strategies for avoiding broken cold chains. Annals of Operations Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-020-03599-4

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge editors and reviewers for their constructive comments. This paper is supported in part by research grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project No.71872125).

Funding

The research is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project No. 71872125).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

We declare that we have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A: Proofs of the piecewise function when N is large

If there are N hotels, and N is even.

For one leisure-traveller who is located at x, \(0\le x\le \frac{\pi *D}{2N}\), we obtain the following if no hotels are removed:

If the leisure-traveller removes one disliked hotel:

If the leisure-traveller removes two disliked hotels:

If the leisure-traveller removes three disliked hotels:

If the leisure-traveller removes four disliked hotels:

If the leisure-traveller removes five disliked hotels:

If the leisure-traveller removes six disliked hotels:

In conclusion, the general formula is given by

The calculation for an odd number of hotels is similar to when there is an even number of hotels; therefore, it is omitted here. The general formulas are symmetrical, whether the number of hotels is even or odd.□

Appendix B: Proofs of Proposition 1

Through Appendix A, we can find that the leisure-travellers’ valuation for the VOP with two hotels is \({\bar{V}}_{2}={V}_{L}-\frac{\pi {*}D}{2N}t\) \((0\le x\le \frac{\pi {*}D}{2N})\), which would not be impacted by the position of leisure-travellers in the circle city; the valuation of the VOP with three hotels is \({\bar{V}}_{3}={V}_{L}-\frac{1}{3}xt-\frac{2\pi {*}D}{3N}t\) \((0\le x\le \frac{\pi {*}D}{2N})\), which is decreasing in x. When \(x=0\), \({\bar{V}}_{3}^{max}={V}_{L}-\frac{2\pi {*}D}{3N}t<{V}_{L}-\frac{\pi {*}D}{2N}t={\bar{V}}_{2}\). The derivation process for the valuation of other VOPs is similar, i.e., \({\bar{V}}_{2}>{\bar{V}}_{n}^{max}\), \(n\ge 3\), that is, the leisure-travellers’ valuation of the VOP with two hotels is higher than any other type of VOPs. In order to maximize the revenue, the OTA will set the price for the VOP with two hotels as \({\bar{V}}_{2}\), and set the price of each other type of VOPs higher than the corresponding highest valuation, in order to make the leisure-travellers give up buying other types of VOPs and only buy the two hotels left on OTA. Therefore, \({p}_{2}^{{*}}={V}_{L}-\frac{\pi {*}D}{2N}t\), \({p}_{3}^{{*}}={V}_{L}-\frac{2\pi {*}D}{3N}t\), \({p}_{4}^{{*}}>{V}_{L}-\frac{\pi {*}D}{N}t\), \({p}_{5}^{{*}}={V}_{L}-\frac{6\pi {*}D}{5N}t\),\({p}_{6}^{{*}}>{V}_{L}-\frac{3\pi {*}D}{2N}t\), \({p}_{7}^{{*}}={V}_{L}-\frac{12\pi {*}D}{7N}t\), \({p}_{8}^{{*}}>{V}_{L}-\frac{2\pi {*}D}{N}t\), and so on.□

Appendix C: Proofs of Proposition 2

When \({p}_{1}\in \left[{V}_{L},{V}_{H}\right]\), the optimal revenue is given by

When \({p}_{1}\in \left[{V}_{L}-\frac{\pi *D}{2N}t,{V}_{L}\right]\), the revenue is derived by

The first order is as follows:

The second order is as follows:

Since \(\frac{{\partial }^{2}{{\Pi }}_{2}}{\partial {p}_{T}^{2}}<0\), maximum revenue can be obtained when

Because \(0\le x\le \frac{\pi *D}{2N}\), we can get that \( V_{L} - \frac{{\pi *D}}{{2N}}t \le p_{1} \le V_{L} ,{\text{~}}0 \le \rho \le \frac{1}{2} \).

We obtain the optimal revenue

Then,\({\Delta }{\Pi }={{\Pi }}_{2}^{*}-{{\Pi }}_{1}^{*}\)

Taking the derivative of \({\Delta }{\Pi }\) with respect of \(\rho \)

We can conclude that \(\Delta {\Pi }\) is a decreasing function of \(\rho \), when \(\rho =0,{\Delta }{\Pi }=\frac{\pi *{D}^{2}*t}{8N}>0\). When \(\rho =\frac{1}{2},{\Delta }{\Pi }=\frac{D \left({V}_{L}-{V}_{H}\right)}{2}<0\).

Therefore, there must be \(\bar{\rho }\in \left[0,\frac{1}{2}\right]\); when \(\rho {\epsilon }\left[0,\bar{\rho }\right]\), \({\Delta }{\Pi }\ge 0\), when \(\rho {\epsilon }\left[\bar{\rho },1\right]\), \({\Delta }{\Pi }\le 0\).□

Appendix D: Proofs of Corollary 4

From Case I and Case II, we can get that \({{\Pi }}_{1}^{D}={{\Pi }}_{1}^{*}={D*\rho *V}_{H}+D*\left(1-\rho \right)*\left({V}_{L}-\frac{\pi *D}{2N}t\right)\), \({{\Pi }}_{2}^{D}={{\Pi }}_{2}^{*}=D*\rho *\left({V}_{L}-\frac{\pi *D}{4N}\left(\frac{1-2\rho }{1-\rho }\right)t\right)+\frac{2N*D*(1-\rho )}{\pi *D}\left(\left({V}_{L}-\frac{\pi *D}{4N}\left(\frac{1-2\rho }{1-\rho }\right)t\right)*\left(\frac{\pi *D}{4N}\left(\frac{1-2\rho }{1-\rho }\right)\right)+\left({V}_{L}-\frac{\pi *D}{2N}t\right)\left(\frac{\pi *D}{2N}-\left(\frac{\pi *D}{4N}\left(\frac{1-2\rho }{1-\rho }\right)\right)\right)\right)\).

When the OTA only adopts the traditional channel, we can get the following piecewise revenue function

:

For \({{\Pi }}_{1}^{D}\) and \({{\Pi }}_{1}^{S}\), as long as \({V}_{L}-\frac{\pi *D}{2N}t\ge 0\) is satisfied, the dual channel is always better than the single channel, and the closer \(\rho \) is to 1, the closer \({{\Pi }}_{1}^{S}\) is to \({{\Pi }}_{1}^{D}\).

For \({{\Pi }}_{2}^{D}\) and \({{\Pi }}_{2}^{S}\), \(\frac{\partial {{\Pi }}_{2}^{S}}{\partial {p}_{1}^{S}}=D*\rho +\frac{2N\left(1-\rho \right)}{\pi *t}\left({V}_{L}-2{p}_{1}^{S}\right)=0,{p}_{1}^{S}=\frac{1}{2}{V}_{L}+\frac{D*\rho *\pi *t}{4N*(1-\rho )}\), \(\frac{{\partial }^{2}{{\Pi }}_{2}^{S}}{\partial {\left({p}_{1}^{S}\right)}^{2}}<0\).

There are some leisure-travellers who will buy in the traditional channel, so \({p}_{1}^{S}<{V}_{L}\), \({p}_{1}^{D}<{V}_{L}\), \(\rho <\frac{1}{2}.\) In order to introduce the opaque channel, we must ensure that \({{V}}_{{L}}-\frac{\pi *D}{2N}{t}\ge 0\).\({p}_{1}^{D}-{p}_{1}^{S}={V}_{L}-\frac{\pi *D}{4N}\left(\frac{1-2\rho }{1-\rho }\right)t-\left(\frac{1}{2}{V}_{L}+\frac{D*\rho *\pi *t}{4N*\left(1-\rho \right)}\right)=\frac{1}{2}{V}_{L}-\frac{\pi *D}{4N}t>0\), so we can get \({p}_{T}^{S}<{p}_{T}^{D}<{V}_{L}\). Because \(x\le \frac{\pi *D}{2N}\), \(\frac{{V}_{L}-{p}_{1}^{S}}{t}\le \frac{\pi *D}{2N}\to \frac{1}{2}{V}_{L}+\frac{D*\rho *\pi *t}{4N*\left(1-\rho \right)}\ge {V}_{L}-\frac{\pi *D}{2N}t\), so \(\rho \ge 1-\frac{\pi *D*t}{2{V}_{L}*N-\pi *D*t},\) \(1-\frac{\pi *D*t}{2{V}_{L}*N-\pi *D*t}<\frac{1}{2}\to {V}_{L}<\frac{3*\pi *D}{2N}t\). When \({V}_{L}<\frac{3*\pi *D}{2N}t\), the above proof results exist.□

\(\Delta {\Pi }={{\Pi }}_{2}^{D}-{{\Pi }}_{2}^{S}=D*\rho *{p}_{1}^{D}+\frac{2N*D*\left(1-\rho \right)}{\pi *D}\left({p}_{1}^{D}*\frac{{V}_{L}-{p}_{1}^{D}}{t}+\left({V}_{L}-\frac{\pi *D}{2N}t\right)\left(\frac{\pi *D}{2N}-\frac{{V}_{L}-{p}_{1}^{D}}{t}\right)\right)-\left(D*\rho {*p}_{1}^{S}+\frac{2N*D*\left(1-\rho \right)}{\pi *D}\frac{{V}_{L}-{p}_{1}^{S}}{t}{p}_{1}^{S}\right)=D*\rho *\left({p}_{1}^{D}-{p}_{1}^{S}\right)+\frac{2N*D*\left(1-\rho \right)}{\pi *D}\left(\frac{{V}_{L}}{t}\left({p}_{1}^{D}-{p}_{1}^{S}\right)-\frac{\left({p}_{1}^{D}-{p}_{1}^{S}\right)\left({p}_{1}^{D}+{p}_{1}^{S}\right)}{t}+\left({V}_{L}-\frac{\pi *D}{2N}t\right)\left(\frac{\pi *D}{2N}-\frac{{V}_{L}-{p}_{1}^{D}}{t}\right)\right)\), \({p}_{1}^{D}-{p}_{1}^{S}=\frac{1}{2}{V}_{L}-\frac{\pi *D}{4N}t\), \(\Delta {\Pi }=\left({V}_{L}-\frac{\pi *D*t}{2N}\right)\left(\frac{\pi *D*t*\left(3+2\rho \right)-3\rho *t+2N*{V}_{L}*\left(\rho -1\right)}{4\pi *t}\right)\). We know that \({V}_{L}<\frac{3*\pi *D}{2N}t\) and \({V}_{L}-\frac{\pi *D}{2N}t>0\) from the above analysis, then we can derive that \(\rho >\frac{2N*{V}_{L}-3\pi *D*t}{2N*{V}_{L}+2\pi *D*t-3t}\), so \(\Delta {\Pi }>0\).□

Appendix E: Proofs of Proposition 3

From Appendix B we can get that \({\Delta }{\Pi }={{\Pi }}_{2}^{*}-{{\Pi }}_{1}^{*}\)

Then making \({\Delta }{\Pi }=0\), it can be derived that \(\frac{1-2\bar{\rho }}{\bar{\rho }}\left(\frac{1-2\bar{\rho }}{1-\bar{\rho }}+\frac{2\bar{\rho }}{1-\bar{\rho }}-2\right)=\frac{8N*\left({V}_{L}-{V}_{H}\right)}{\pi *D*t}\), \({\left(\bar{\rho }-\frac{1}{2}\right)}^{2}=\frac{2N\left({V}_{H}-{V}_{L}\right)}{8N\left({V}_{H}-{V}_{L}\right)+4\pi *D*t}\), for \(\bar{\rho }\in \left[0,\frac{1}{2}\right]\), so \(\frac{1}{2}-\bar{\rho }=\sqrt{\frac{2N\left({V}_{H}-{V}_{L}\right)}{8N\left({V}_{H}-{V}_{L}\right)+4\pi *D*t}}\), \(\bar{\rho }=\frac{1}{2}-\sqrt{\frac{N\left({V}_{H}-{V}_{L}\right)}{4N\left({V}_{H}-{V}_{L}\right)+2\pi *D*t}}\).□

Appendix F: Proofs of Proposition 5

We know that \({{\Pi }}_{1}^{*}={D*\rho *V}_{H}+D*\left(1-\rho \right)*\left({V}_{L}-\frac{\pi *D}{2N}t\right)\) in Sect. 4, \(\frac{\partial {{\Pi }}_{1}^{*}}{\partial D}=\rho *{V}_{H}+\left(1-\rho \right)*\left(1-\frac{\pi *D*t}{N}\right)\), when \(D\le \frac{N}{\pi *t}*\left(1+\frac{\rho }{1-\rho }*{V}_{H}\right)\), \(\frac{\partial {{\Pi }}_{1}^{*}}{\partial D}\ge 0\), \({{\Pi }}_{1}^{*}\) increases in D; while \(D>\frac{N}{\pi *t}*\left(1+\frac{\rho }{1-\rho }*{V}_{H}\right)\), \(\frac{\partial {{\Pi }}_{1}^{*}}{\partial D}<0\), \({{\Pi }}_{1}^{*}\) decreases in D, we know that the price in the opaque channel decreases in D, in order to get a positive price, we make \({p}_{2}^{*}={V}_{L}-\frac{\pi *D}{2N}t\ge 0, D\le \frac{2N*{V}_{L}}{\pi *t}.\) \({{\Pi }}_{2}^{*}=D*\rho *\left({V}_{L}-\frac{\pi *D}{4N}\left(\frac{1-2\rho }{1-\rho }\right)t\right)+\frac{2N*D*\left(1-\rho \right)}{\pi *D}\left(\left({V}_{L}-\frac{\pi *D}{4N}\left(\frac{1-2\rho }{1-\rho }\right)t\right)*\frac{\pi *D}{4N}\left(\frac{1-2\rho }{1-\rho }\right)+\left({V}_{L}-\frac{\pi *D}{2N}t\right)\left(\frac{\pi *D}{2N}-\frac{\pi *D}{4N}\left(\frac{1-2\rho }{1-\rho }\right)\right)\right)=D*\rho *\left({V}_{L}-\frac{\pi *D}{4N}\left(\frac{1-2\rho }{1-\rho }\right)t\right)+\left(\frac{D*\left(1-2\rho \right)}{2}*\left({V}_{L}-\frac{\pi *D*t*\left(1-2\rho \right)}{4N*\left(1-\rho \right)}\right)+\frac{D}{2}*\left({V}_{L}-\frac{\pi *D*t}{2N}\right)\right)=\frac{D}{2}*\left(2{V}_{L}-\frac{\pi *D*t*\left(2-3\rho \right)}{4N*\left(1-\rho \right)}\right)\), \(\frac{\partial {{\Pi }}_{2}^{*}}{\partial D}={V}_{L}-\frac{\pi *D*t*\left(2-3\rho \right)}{4N\left(1-\rho \right)}\), when \(D\le \frac{4N*{V}_{L}*\left(10\rho \right)}{\pi *t*\left(2-3\rho \right)}\), \(\frac{\partial {{\Pi }}_{2}^{*}}{\partial D}\ge 0\), \({{\Pi }}_{2}^{*}\) increases in D; while \(D>\frac{4N*{V}_{L}*\left(10\rho \right)}{\pi *t*\left(2-3\rho \right)}\), \(\frac{\partial {{\Pi }}_{2}^{*}}{\partial D}<0\), \({{\Pi }}_{*}^{2}\) decreases in D. For positive price from both the traditional and opaque channel, we make \({p}_{1}^{*}\ge 0\) and \({p}_{2}^{*}\ge 0\), \(D\le min\left(\frac{1-\rho }{1-2\rho }\frac{4N*{V}_{L}}{\pi *t}, \frac{2N*{V}_{L}}{\pi *t}\right)=\frac{2N*{V}_{L}}{\pi *t}.\)□

Appendix G: Proofs of Corollary 5

As the city circle expands, the number of travellers also increases proportionally, namely, the distribution density of leisure-travellers remains unchanged. Here, only the circular arc length is calculated, which is equivalent to the increase in the number of travellers. The superscript “+” represents the situation after the city circle expansion. \(\Delta {T}={\underset{\raise0.3em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle-}$}}{x}}^{+}-\underset{\raise0.3em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle-}$}}{x}=\frac{{V}_{L}-{p}_{1}^{+}}{t}-\frac{{V}_{L}-{p}_{1}}{t}=\frac{{V}_{L}-\frac{\pi *D*t*\left(1-2\rho \right)}{4N*\left(1-\rho \right)}-{V}_{L}+\frac{\pi *{D}^{+}*t*\left(1-2\rho \right)}{4N*\left(1-\rho \right)}}{t}=\frac{\pi *\left({D}^{+}-D\right)*\left(1-2\rho \right)}{4N*\left(1-\rho \right)}\), and \(\Delta {O}=\frac{\pi *{D}^{+}}{2N}-\frac{\pi *D}{2N}-\left({\underset{\raise0.3em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle-}$}}{x}}^{+}-\underset{\raise0.3em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle-}$}}{x}\right)=\frac{\pi *\left({D}^{+}-D\right)}{4N}*\left(2-\frac{1-2\rho }{1-\rho }\right)=\frac{\pi *\left({D}^{+}-D\right)}{4N}*\left(\frac{1}{1-\rho }\right)\), then \(\Delta {T}-\Delta {O}=\frac{\pi *\left({D}^{+}-D\right)}{4N}*\left(\frac{-2\rho }{1-\rho }\right)<0\), therefore \(\Delta {T}<\Delta {O}\), and \(\frac{\Delta {T}}{\Delta {O}}=1-2{\rho }\).□

Appendix H: Proofs of Proposition 6

From the above analysis, \({{\Pi }}_{2}^{*}=\frac{{D}_{T}}{2}*\left(2{V}_{L}-\frac{\pi *D*t*\left(2-3\rho \right)}{4N*\left(1-\rho \right)}\right)\), \(\frac{\partial {{\Pi }}_{2}^{*}}{\partial D}=-\frac{\pi *{D}_{T}*t*\left(2-3\rho \right)}{8N*\left(1-\rho \right)}<0\), so \({{\Pi }}_{2}^{*}\) decreases in D.□

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mao, Z., Liu, T. & Li, X. Pricing mechanism of variable opaque products for dual-channel online travel agencies. Ann Oper Res 329, 901–930 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-021-04163-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-021-04163-4